Economic and monetary developments

Overview

After the contraction in the first quarter of the year, the euro area economy is gradually reopening as the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic situation improves and vaccination campaigns make significant progress. The latest data signal a bounce-back in services activity and ongoing dynamism in manufacturing production. Economic activity is expected to accelerate in the second half of this year as further containment measures are lifted. A pick-up in consumer spending, strong global demand and accommodative fiscal and monetary policies will lend crucial support to the recovery. At the same time, uncertainties remain, as the near-term economic outlook continues to depend on the course of the pandemic and on how the economy responds after reopening. Inflation has picked up over recent months, largely on account of base effects, transitory factors and an increase in energy prices. It is expected to rise further in the second half of the year, before declining as temporary factors fade out. The new staff projections point to a gradual increase in underlying inflation pressures throughout the projection horizon, although the pressures remain subdued in the context of still significant economic slack that will only be absorbed gradually over the projection horizon. Headline inflation is expected to remain below the Governing Council’s aim over the projection horizon.

Preserving favourable financing conditions over the pandemic period remains essential to reduce uncertainty and bolster confidence, thereby underpinning economic activity and safeguarding medium-term price stability. Financing conditions for firms and households have remained broadly stable since the Governing Council’s monetary policy meeting in March. However, market interest rates have increased further. While partly reflecting improved economic prospects, a sustained rise in market rates could translate into a tightening of wider financing conditions that are relevant for the entire economy. Such a tightening would be premature and would pose a risk to the ongoing economic recovery and the outlook for inflation. Against this background and based on a joint assessment of financing conditions and the inflation outlook, the Governing Council decided to confirm its very accommodative monetary policy stance.

Economic and monetary assessment at the time of the Governing Council meeting of 10 June 2021

The June 2021 Eurosystem staff macroeconomic projections suggest that global economic activity continued to recover at the turn of the year despite the intensification of the pandemic, with emerging market economies becoming the epicentre of new infections globally. While activity in the fourth quarter of 2020 turned out to be slightly stronger than expected in the previous projections, the global economy entered 2021 on a weaker footing amid a resurgence in new infections and tighter containment measures. Recent surveys signal strong momentum in global activity, although signs of divergence between advanced and emerging market economies, and between the manufacturing and services sectors, are becoming more apparent. The large fiscal stimulus approved by the Biden administration is projected to strengthen the recovery in the United States, with some positive global spillovers. Against this backdrop, the growth outlook for the global economy is little changed compared to the previous projections. Global real GDP growth (excluding the euro area) is projected to increase by 6.2% this year, before slowing to 4.2% and 3.7% in 2022 and 2023 respectively. However, euro area foreign demand was revised upwards compared with the previous projections. It is projected to increase by 8.6% this year and by 5.2% and 3.4% in 2022 and 2023 respectively. This mainly reflects stronger demand from the United States and the United Kingdom, the euro area’s key trading partners. The export prices of euro area competitors were revised upwards for this year amid higher commodity prices and stronger demand. Risks to the global baseline projections relate mainly to the future course of the pandemic. Other risks to the global outlook for activity are judged to be broadly balanced, while the risks for global inflation are tilted to the upside.

Financial conditions in the euro area have continued to tighten somewhat since the last Governing Council meeting, amid positive risk sentiment. Over the review period (11 March to 9 June 2021), euro area sovereign bond yields and their spreads over the overnight index swap (OIS) rate increased moderately, mainly amid an improved economic outlook in the light of progress in vaccination campaigns across the euro area together with continuing policy support. The forward curve of the euro overnight index average (EONIA) increased marginally across medium to long-term maturities, while the short end of the curve has remained largely the same, suggesting no expectations of an imminent policy rate change in the very near term. Equity prices also increased, supported by a combination of still relatively low discount rates and a strong recovery in corporate earnings growth expectations. Mirroring equity prices, euro area corporate bond spreads continued to tighten and stand at levels last observed prior to March 2020. In foreign exchange markets, the nominal effective exchange rate of the euro strengthened slightly.

In the first quarter of the year, euro area real GDP declined further, by 0.3%, to stand 5.1% below its pre-pandemic level of the fourth quarter of 2019. Business and consumer surveys and high-frequency indicators point to a sizeable improvement in activity in the second quarter of this year. Business surveys indicate a strong recovery in services activity as infection numbers decline, which will allow a gradual normalisation of high-contact activities. Manufacturing production remains robust, supported by solid global demand, although supply-side bottlenecks could pose some headwinds for industrial activity in the near term. Indicators of consumer confidence are strengthening, suggesting a strong rebound in private consumption in the period ahead. Business investment shows resilience, despite weaker corporate balance sheets and the still uncertain economic outlook. Looking ahead, growth is expected to continue to improve strongly in the second half of 2021 as progress in vaccination campaigns allows a further relaxation of containment measures. Over the medium term, the recovery in the euro area economy is expected to be buoyed by stronger global and domestic demand, as well as by continued support from both monetary policy and fiscal policy.

This assessment is broadly reflected in the baseline scenario of the June 2021 Eurosystem staff macroeconomic projections for the euro area. These projections foresee annual real GDP growth at 4.6% in 2021, 4.7% in 2022 and 2.1% in 2023. Compared with the March 2021 ECB staff macroeconomic projections, the outlook for economic activity has been revised up for 2021 and 2022, while it is unchanged for 2023.

Overall, the risks surrounding the euro area growth outlook are broadly balanced. On the one hand, an even stronger recovery could be predicated on brighter prospects for global demand and a faster-than-anticipated reduction in household savings once social and travel restrictions have been lifted. On the other hand, the ongoing pandemic, including the spread of virus mutations, and its implications for economic and financial conditions continue to be sources of downside risk.

According to Eurostat’s flash release, euro area annual inflation increased from 1.3% in March to 1.6% in April and 2.0% in May 2021. This rise was due mainly to a strong increase in energy price inflation, reflecting both sizeable upward base effects as well as month-on-month increases, and, to a lesser extent, a slight increase in non-energy industrial goods inflation. Headline inflation is likely to increase further towards the autumn, reflecting mainly the reversal of the temporary VAT reduction in Germany. Inflation is expected to decline again at the start of next year as temporary factors fade out and global energy prices moderate. Underlying price pressures are expected to increase somewhat this year owing to temporary supply constraints and the recovery in domestic demand. Nevertheless, the price pressures will likely remain subdued overall, in part reflecting low wage pressures, in the context of still significant economic slack, and the appreciation of the euro exchange rate. Once the impact of the pandemic fades, the unwinding of the high level of slack, supported by accommodative monetary and fiscal policies, will contribute to a gradual increase in underlying inflation over the medium term. Survey-based measures and market-based indicators of longer-term inflation expectations remain at subdued levels, although market-based indicators have continued to increase.

This assessment is broadly reflected in the baseline scenario of the June 2021 Eurosystem staff macroeconomic projections for the euro area, which foresees annual inflation at 1.9% in 2021, 1.5% in 2022 and 1.4% in 2023. Compared with the March 2021 ECB staff macroeconomic projections, the outlook for inflation has been revised up for 2021 and 2022, largely owing to temporary factors and higher energy price inflation. It is unchanged for 2023, as the increase in underlying inflation is largely counterbalanced by an expected decline in energy price inflation. HICP inflation excluding energy and food is projected to increase from 1.1% in 2021 to 1.3% in 2022 and 1.4% in 2023, revised up throughout the projection horizon compared with the March 2021 projection exercise.

Money creation in the euro area moderated in April 2021, showing some initial signs of normalisation following the massive monetary expansion associated with the coronavirus crisis. Broad money (M3) growth declined to 9.2% in April 2021, from 10.0% in March and 12.3% in February. The deceleration in March and April was due partly to strong negative base effects as the large inflows in the initial phase of the pandemic crisis dropped out of the annual growth statistics. It also reflects a moderation in shorter-term monetary dynamics, mainly originating from weaker developments in deposits by households and firms in April and lower liquidity needs as the pandemic situation improves. The ongoing asset purchases by the Eurosystem continue to be the largest source of money creation. While also decelerating, the narrow monetary aggregate M1 has remained the main contributor to broad money growth. Its strong contribution is consistent with a still heightened preference for liquidity in the money-holding sector and a low opportunity cost of holding the most liquid forms of money.

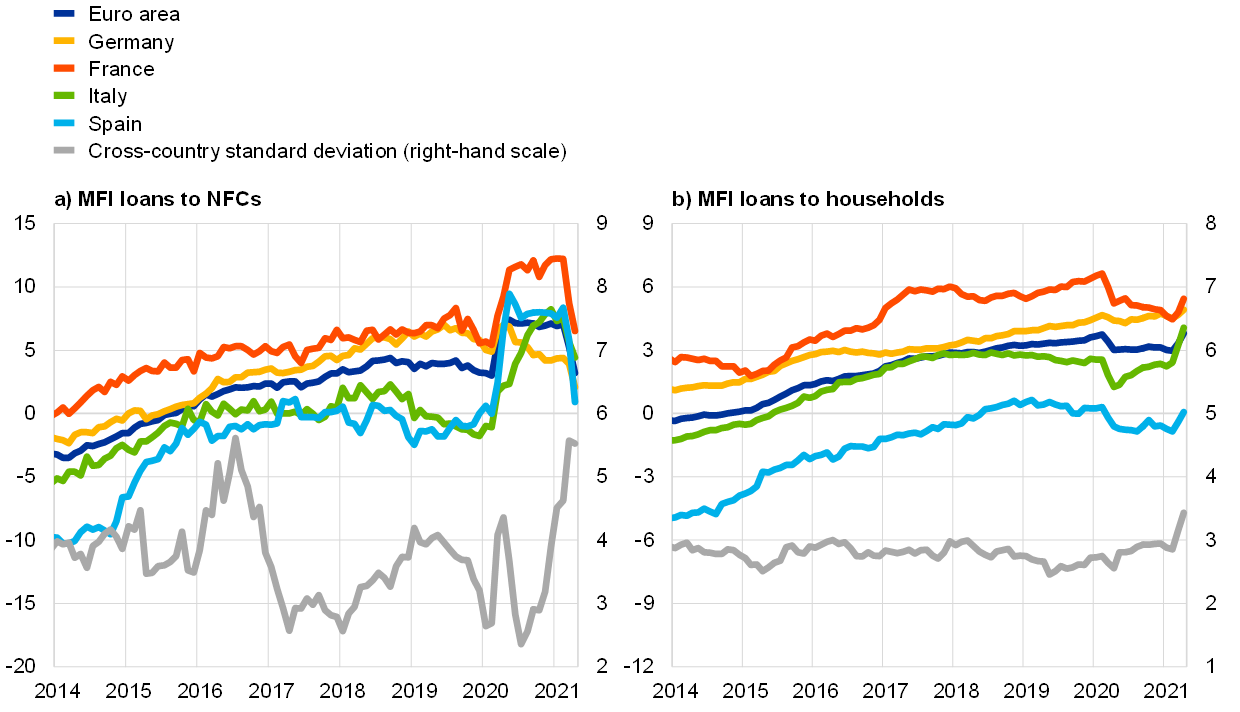

The annual growth rate of loans to the private sector declined to 3.2% in April, from 3.6% in March and 4.5% in February. This decline took place amid opposing dynamics in lending to non-financial corporations and to households. The annual growth rate of loans to non-financial corporations fell to 3.2% in April, after 5.3% in March and 7.0% in February. The contraction reflects large negative base effects and some frontloading in loan creation in March relative to April. The annual growth rate of loans to households rose to 3.8% in April, after 3.3% in March and 3.0% in February, supported by solid monthly flows and positive base effects. Overall, the Governing Council’s policy measures, together with the measures adopted by national governments and other European institutions, remain essential to support bank lending conditions and access to financing, in particular for those most affected by the pandemic.

As a result of the very sharp economic downturn during the coronavirus pandemic and the strong fiscal reaction, the general government budget deficit in the euro area increased strongly, to 7.3% of GDP in 2020 from 0.6% in 2019. This year, as new waves of the pandemic have hit euro area countries, many emergency measures have been extended and additional recovery support has been put in place. As a result, the June 2021 Eurosystem staff macroeconomic projections foresee only a marginal improvement in the general government budget balance in the euro area to -7.1% of GDP in 2021. However, as the pandemic abates and the economic recovery takes hold, the deficit ratio is expected to fall more swiftly, to 3.4% in 2022 and 2.6% at the end of the projection horizon in 2023. Euro area debt is projected to peak at just below 100% of GDP in 2021 and to decline to around 95% of GDP in 2023, which is about 11 percentage points higher than before the coronavirus crisis. Nonetheless, an ambitious and coordinated fiscal stance remains crucial, as a premature withdrawal of fiscal support would risk weakening the recovery and amplifying the longer-term scarring effects. National fiscal policies should thus continue to provide critical and timely support to the firms and households most exposed to the ongoing pandemic and the associated containment measures. At the same time, fiscal measures should remain temporary and countercyclical, while ensuring that they are sufficiently targeted in nature to address vulnerabilities effectively and to support a swift recovery in the euro area economy. As a complement to national fiscal measures, the Next Generation EU package is expected to play a key role by contributing to a faster, stronger and more uniform recovery. It should increase economic resilience and the growth potential of EU Member States’ economies, particularly if the funds are used for productive public spending and are accompanied by productivity-enhancing structural policies. According to the June macroeconomic projections, the combination of Next Generation EU grants and loans should provide additional stimulus of around 0.5% of GDP per year between 2021 and 2023.

The monetary policy decisions

On 10 June 2021 the Governing Council decided to reconfirm its very accommodative monetary policy stance in order to preserve favourable financing conditions for all sectors of the economy, which is needed for a sustained economic recovery and for safeguarding price stability.

- The Governing Council decided to keep the key ECB interest rates unchanged. They are expected to remain at their present or lower levels until the inflation outlook robustly converges to a level sufficiently close to, but below, 2% within the projection horizon, and such convergence has been consistently reflected in underlying inflation dynamics.

- The Governing Council will continue to conduct net asset purchases under the pandemic emergency purchase programme (PEPP) with a total envelope of €1,850 billion until at least the end of March 2022 and, in any case, until the Governing Council judges that the coronavirus crisis phase is over. Based on a joint assessment of financing conditions and the inflation outlook, the Governing Council expects net purchases under the PEPP over the coming quarter to continue to be conducted at a significantly higher pace than during the first months of the year. The Governing Council will purchase flexibly according to market conditions and with a view to preventing a tightening of financing conditions that is inconsistent with countering the downward impact of the pandemic on the projected path of inflation. In addition, the flexibility of purchases over time, across asset classes and among jurisdictions will continue to support the smooth transmission of monetary policy. If favourable financing conditions can be maintained with asset purchase flows that do not exhaust the envelope over the net purchase horizon of the PEPP, the envelope need not be used in full. Equally, the envelope can be recalibrated if required to maintain favourable financing conditions to help counter the negative pandemic shock to the path of inflation. Furthermore, the Governing Council will continue to reinvest the principal payments from maturing securities purchased under the PEPP until at least the end of 2023. In any case, the future roll-off of the PEPP portfolio will be managed to avoid interference with the appropriate monetary policy stance.

- Net purchases under the asset purchase programme (APP) will continue at a monthly pace of €20 billion. The Governing Council continues to expect monthly net asset purchases under the APP to run for as long as necessary to reinforce the accommodative impact of the ECB’s policy rates, and to end shortly before the Governing Council starts raising the key ECB interest rates. In addition, the Governing Council intends to continue reinvesting, in full, the principal payments from maturing securities purchased under the APP for an extended period of time past the date when it starts raising the key ECB interest rates, and in any case for as long as necessary to maintain favourable liquidity conditions and an ample degree of monetary accommodation.

- Finally, the Governing Council will continue to provide ample liquidity through its refinancing operations. The funding obtained through the third series of targeted longer-term refinancing operations (TLTRO III) plays a crucial role in supporting bank lending to firms and households.

The Governing Council will also continue to monitor developments in the exchange rate with regard to their possible implications for the medium-term inflation outlook. It stands ready to adjust all of its instruments, as appropriate, to ensure that inflation moves towards its aim in a sustained manner, in line with its commitment to symmetry.

1 External environment

The June 2021 Eurosystem staff macroeconomic projections suggest that global economic activity continued to recover at the turn of the year. While activity in the fourth quarter of 2020 turned out to be slightly stronger than had been expected in the previous projections, the global economy entered 2021 on a weaker footing amid a resurgence in new infections and tighter containment measures. Recent surveys signal strong momentum in global activity, although signs of divergence between advanced and emerging market economies, and between the manufacturing and services sectors are becoming more apparent. The large fiscal stimulus approved by the Biden administration is projected to strengthen the recovery in the United States, with some positive global spillovers. Against this backdrop, the growth outlook for the global economy is little changed compared to the previous projections. Global real GDP (excluding the euro area) is projected to increase by 6.2% this year, before slowing to 4.2% in 2022 and 3.7% in 2023. However, euro area foreign demand was revised upwards compared with the previous projections. It is projected to increase by 8.6% this year and by 5.2% and 3.4% in 2022 and 2023 respectively. This mainly reflects stronger demand from the United States and the United Kingdom, the euro area’s key trading partners. The export prices of euro area competitors were revised upwards for this year amid higher commodity prices and stronger demand. Risks to the global baseline projections relate mainly to the future course of the pandemic. Other risks to the global outlook for activity are judged to be broadly balanced, while the risks for global inflation are tilted to the upside.

Global economic activity and trade

Global economic activity continued to recover at the turn of the year despite the intensification of the pandemic. Global real GDP growth (excluding the euro area) increased by 2.6% quarter on quarter in the fourth quarter of 2020, which was stronger than had been expected in the March 2021 ECB staff macroeconomic projections. However, the global economy entered the year on a weaker footing, as a resurgence in new infections led governments to tighten containment measures. Consequently, global real GDP growth (excluding the euro area) is estimated to have slowed markedly to 0.7% quarter on quarter in the first quarter of 2021. This pattern reflects slower growth in advanced and emerging market economies alike. At the same time, activity in advanced economies was more resilient than had been expected in the previous projections, as households and firms adapted better to lockdowns, and additional policy stimulus was implemented. The slowdown in emerging market economies (EMEs), by contrast, turned out to be more pronounced.

The pandemic intensified in EMEs, while the situation in advanced economies improved markedly with the roll-out of vaccination campaigns. Earlier this year, the situation also deteriorated in Europe, while the rapid pace of vaccination in the United Kingdom and the United States helped to push down the number of new infections in advanced economies overall. The pandemic situation in EMEs remains precarious and continues to be the key factor shaping economic developments across countries.

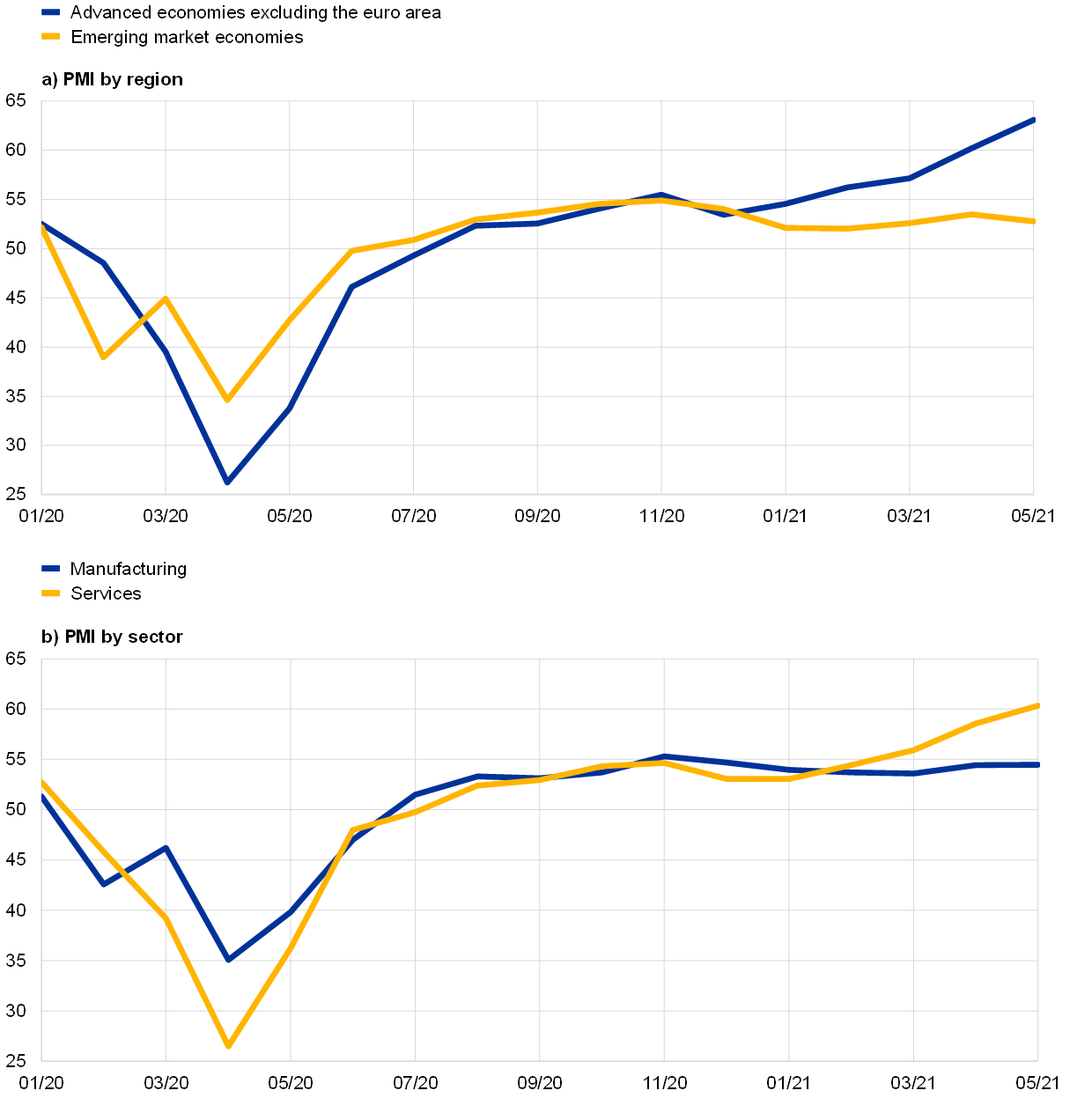

At the current juncture, survey data signal strong momentum in global activity amid more apparent signs of divergence across countries and sectors. The global composite output PMI increased to 58.8 in May – well above its long-term average and also outside its historical interquartile range. While the strong momentum is generally visible across both the manufacturing and the services sectors, lately some differences across countries and sectors have become more apparent. First, the growth momentum in advanced economies is solid and has recently strengthened further. This contrasts with EMEs, where activity continues to improve at a slower pace (Chart 1, upper panel). Second, there was a sharp pick-up in the pace of economic expansion in the services sector as restrictions were lifted. This rapid expansion should also be seen in the context of the recovery starting from low levels, especially in contact-intensive services. By contrast, manufacturing output, which proved more resilient at the height of the pandemic, continues to grow at a slower, albeit still buoyant, pace amid some headwinds created by supply constraints (Chart 1, lower panel).

Chart 1

Global (excluding the euro area) output PMI by regions and sectors

(diffusion indices)

Sources: Markit and ECB calculations.

Note: The latest observations are for May 2021.

The global recovery has been supported by very accommodative financial conditions. In both advanced and emerging market economies, financial conditions remain supportive, as rising bond yields were offset by higher equity prices and narrowing corporate bond spreads.

The near-term outlook for the global economy continues to be shaped by the potential course of the pandemic. In advanced economies outside the euro area, the swift roll-out of vaccinations holds the promise that the pandemic can be contained, economies can gradually re-open and then recover rather quickly. This contrasts with the pandemic situation in some large EMEs, where economic activity is expected to have weakened further despite the relatively limited restrictions on mobility implemented by authorities to date.

Some positive spillovers to the global economy are expected from the large fiscal stimulus approved by the Biden administration, which will strengthen the recovery in the United States. The American Rescue Plan (ARP), totalling USD 1.9 trillion (8.9% of GDP), includes a renewal of unemployment benefits, additional one-off payments to households and an increase in both local and state spending to finance public health efforts and education. Additional stimulus checks sent out since the ARP was signed into law in mid-March are projected to stimulate private consumption in the coming quarters, leading to positive spillovers to other countries through trade linkages. Meanwhile, the Biden administration announced two new medium-term fiscal plans, namely the American Jobs Plan and the American Families plan. The former proposes a variety of infrastructure investments to be partly financed by higher corporate income taxes, while the latter focuses on social welfare spending and tax credits, and is almost fully financed by higher personal income taxes. Overall, the impact of the two plans on economic activity is estimated to be more limited compared with the ARP owing to their decade-long implementation and the fact that they will be funded by higher taxes.

The growth outlook for the global economy is little changed compared to the previous projections. Global real GDP (excluding the euro area) is projected to increase by 6.2% this year, before slowing to 4.2% in 2022 and 3.7% in 2023. It has been revised downwards by 0.3 percentage points in 2021 and upwards by 0.3 percentage points in 2022 compared with the previous projections, and remained unchanged for 2023. This pattern reflects an interplay of factors, including a worsening of the pandemic in advanced economies at the beginning of this year and in EMEs more recently, as well as the macroeconomic impact of the large fiscal stimulus in the United States and an improving outlook in other advanced economies as a result of the fast vaccine roll-out. Among EMEs, in India the near-term outlook worsened significantly owing to a deterioration in epidemiological conditions. However, mobility and economic indicators suggest that the fallout from the current wave may not be as severe as that observed last spring.

In the United States, economic activity is projected to expand on the back of strong policy support and a gradual reopening of the economy. Following solid quarter-on-quarter annualised growth of 6.4% in the first quarter of 2021, activity is expected to pick up further in the second quarter amid strong consumer spending supported by the disbursement of government direct income support to households. Meanwhile, in the labour market, the vacancy rate stood at elevated levels, while the unemployment rate continued to be relatively high. This suggests that skills mismatches in the labour market and a shortage of workers in contact-intensive services sectors may create some headwinds as the economy reopens. Employment surveys indicate that growth in hourly earnings accelerated in April, and the number of hours worked per week jumped to an all-time high, in particular in industries with a large number of vacancies, such as food services. Headline annual consumer price inflation increased to 4.2% in April. While the rise in headline inflation resulted mainly from a strong annual increase in the energy component, core inflation also increased significantly as sectors hit hard by the pandemic have increased prices significantly as the economy reopens, for example prices of air fares and accommodation. Disruption to global supply chains weighed on car production in the United States and is likely to have contributed to higher prices for used cars in April.

In the United Kingdom, fiscal spending and the extension of key measures taken in response to the coronavirus are expected to support the economy. Real GDP growth contracted by 1.5% in the first quarter of 2021, when a strict lockdown was in place. This relatively mild contraction suggests that firms and households adapted well to government restrictions. Private consumption contributed negatively nonetheless, as did the significant reversal of the stocks built up late last year in response to fears of a “no-deal” Brexit. However, towards the end of the first quarter, as vaccination progressed and restrictions on mobility were gradually eased, economic activity started to pick up. Business surveys, consumer confidence and mobility trackers all signal a strong rebound in the second quarter. Annual consumer price inflation increased to 1.5% in April, up from 0.7% in the previous month, while core inflation increased to 1.3% in April, up from 1.1% in March. The rise in inflation was mostly driven by energy prices as the recent rise in oil prices started to feed through to household energy prices, adding to the increase in transport prices. Looking ahead, headline inflation is expected to continue to rise towards the Bank of England’s 2% target over the next few months, mainly owing to base effects stemming from weak price pressures in spring 2020 and the impact of recent rises in energy prices.

In China, economic activity is expected to continue to grow at a steady pace over the projection horizon. In May survey data pointed to a steady growth momentum. This followed weaker than expected outturns in industrial production and retail sales growth in the previous month, while in April export growth was solid and is becoming broader based against the backdrop of stronger global demand. Expansionary policies also continued to support the recovery, although the policy stance is gradually becoming more balanced. Looking ahead, the main driver of economic activity is expected to switch from investment to private consumption as the outlook for employment and income firms up. Annual headline consumer price inflation increased modestly to 1.3% in May, up from 0.9% in April. Consumer price inflation remains subdued overall. While energy prices increased markedly, the recovery in pork meat supply, following last year’s outbreak of African swine fever, is keeping food price inflation contained. Meanwhile, annual producer price inflation increased to 9.0% in May.

In Japan, the recovery is expected to resume more firmly later this year and to proceed at a moderate pace thereafter. Stronger domestic demand following an easing of containment measures, as well as continued fiscal support and recovering external demand, are expected to support the gradual but steady recovery. Real GDP fell by 1.3% in the first quarter of 2021, as the second state of emergency, enacted between early January and mid-March, weighed on private consumption and business investment. The third state of emergency announced in late-April and limited progress on vaccination are likely to defer a firmer recovery to the second half of this year. Annual headline CPI inflation stood at -0.4% in April, as the impact of rising energy prices was outweighed by a sharp decline in mobile phone charges. Annual CPI inflation is projected to rise gradually over the projection horizon, but to remain below the Bank of Japan’s target.

In central and eastern European EU Member States, the recovery slowed significantly at the turn of the year. It is expected to decelerate further in the near term as the worsened pandemic conditions continue to weigh on activity. Once lockdowns are eased and progress is made on vaccinations, activity is forecast to gradually regain momentum, supported by accommodative fiscal and monetary policies.

In large commodity-exporting countries, economic activity is recovering as global demand strengthens. In Russia, following a relatively mild recession last year, economic activity in the first quarter was estimated to increase slightly. Looking ahead, stronger global demand for oil, together with a rebound in consumption and investment, are expected to support activity over the projection horizon. In Brazil, activity continued to recover in the first quarter and stood close to its pre-pandemic levels despite the resurgence in new infections. Looking ahead stronger foreign demand and private consumption are expected to drive the recovery. By contrast, monetary policy has recently been tightening, while fiscal space continues to be limited.

In Turkey, domestic demand is slowing amid the gradual withdrawal of credit stimulus. Furthermore, increased policy uncertainty and weakened market confidence continue to weigh on near-term economic prospects. The impact of weaker domestic absorption on economic activity has been offset by stronger export performance in the first quarter of 2021. Looking ahead, provided that the recent shift in policy direction towards macroeconomic stability is sustained, real GDP growth is likely to remain subdued but more balanced.

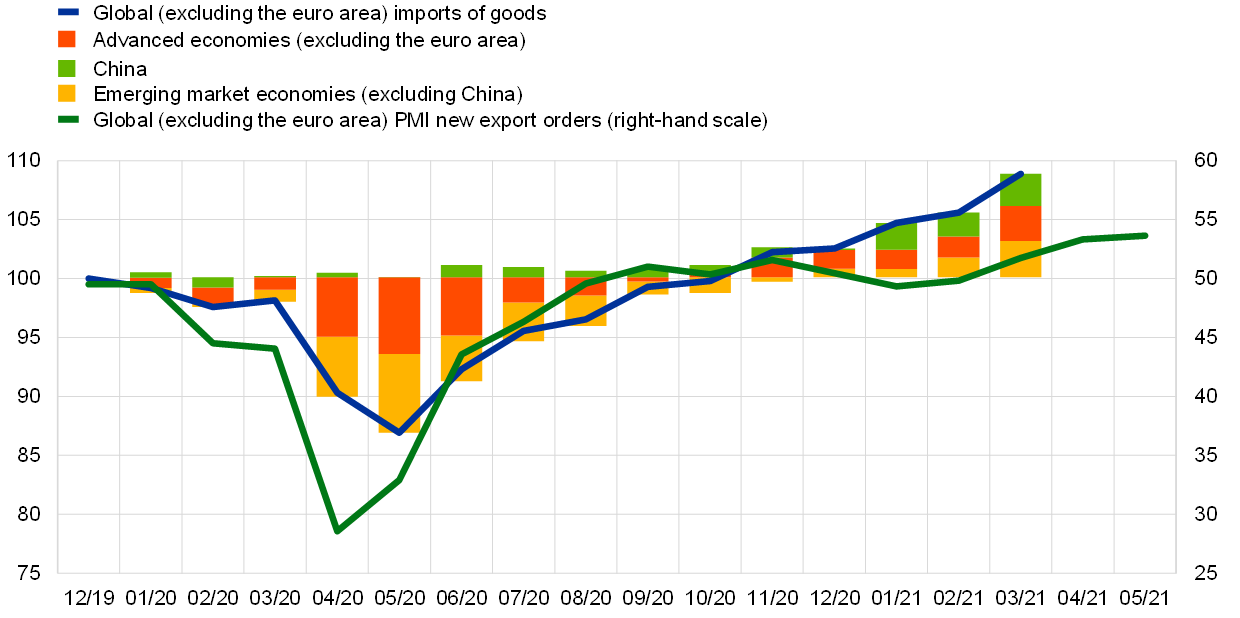

The recovery in global trade proceeds unabated as domestic demand strengthens in advanced economies and China. Following the dynamic recovery in global goods imports (excluding the euro area) in late 2020, growth momentum has slowed somewhat more recently. The recovery is mainly driven by an improvement in domestic absorption in key advanced economies and in China, despite some higher volatility recorded around the Lunar New Year holiday period (Chart 2). While international trade in services is picking up steam, its ascent from the trough reached in late spring 2020 remains gradual, as containment measures and travel restrictions remain in place. In the near term the recovery in trade is expected to proceed unabated. The PMI manufacturing new export orders index increased further in May, staying well above its long-term average, suggesting a further acceleration in global trade in the near term. However, disruptions in global supply chains continue to create headwinds to the recovery of global trade. High-frequency indicators of supply chain bottlenecks, such as the PMIs for work backlogs, have risen to their highest levels since the aftermath of the global financial crisis, while PMI supplier delivery times lengthened and now stand close to the all-time high registered at the peak of the pandemic. Furthermore, the high level of the PMI new order-to-inventory ratio and PMI backlog of work signal that production is struggling to meet strong and rising demand, especially in the technology and automobile industries.

Chart 2

Global (excluding the euro area) imports of goods and new export orders

(left-hand scale: index, December 2019 = 100; right-hand scale: diffusion index)

Sources: Markit, CPB Netherlands Bureau for Economic Policy Analysis and ECB calculations.

Note: The latest observations are for May 2021 for the PMI data and March 2021 for global merchandise imports.

The improved outlook in key trading partners of the euro area led to stronger euro area foreign demand. Euro area foreign demand is forecast to expand by 8.6% this year and by 5.2% and 3.4% in 2022 and 2023 respectively – an upward revision for all three years compared with the March 2021 ECB staff macroeconomic projections. This mainly reflects the stronger than projected demand from the United States and the United Kingdom, notwithstanding weaker than expected outturns in the first quarter. Overall, more positive outturns at the start of the year and an improved outlook in some key euro area trading partners imply that the gap in the trajectory of global trade relative to the pre-pandemic path has narrowed further. Global imports (excluding the euro area) were also revised upwards over the projection horizon and are expected to increase by 10.8% in 2021, before slowing to 4.9% in 2022 and 3.7% in 2023.

Risks to the baseline projections for global growth are judged to be broadly balanced, while those for global inflation are tilted to the upside. In line with the previous projection rounds, two alternative scenarios for the global outlook are used to illustrate the uncertainty surrounding the future course of the pandemic. These scenarios reflect the interplay between developments in the pandemic and the associated path of containment measures.[1] Other risks to the global outlook for activity relate to a faster than currently projected unwinding of excess savings built up across advanced economies during the pandemic. This could lead to stronger private consumption in these economies and thus activity and inflation. Prospects of a stronger and faster recovery in advanced economies may alter market participants’ expectations about global monetary policy prospects and increase the risk of repricing in global financial markets. This kind of repricing commonly weighs more on EMEs, especially those with weak fundamentals. It would accentuate the risks associated with high indebtedness across advanced and emerging market economies. If disruptions in global supply chains are more protracted than currently assumed, stronger inflationary pressures and headwinds to the recovery in global activity and trade could result.

Global price developments

Global commodity prices have increased further since the previous projections. The price rally that had already started last summer halted temporarily in March amid volatile market sentiment in the face of rising sovereign bond yields. This led to a slight correction in oil prices, while food and metals prices have remained broadly stable. Since then, however, prices have moved higher, as accommodative policies coupled with the ongoing vaccine roll-out and expected lifting of containment measures have led to an improved demand outlook for commodities. According to the International Energy Agency, global oil demand is expected to recover most of the volume lost during the pandemic by the end of 2021. Against this backdrop, OPEC+ has gradually revised its production targets upwards, which also includes the phasing-out of the unilateral production cuts by Saudi Arabia. Overall, global oil prices are being shaped by a combination of stronger demand and gradually increasing supply and are also underpinned by a positive global risk sentiment.

Global consumer price inflation is projected to increase amid higher commodity prices and recovering demand. However, the projected increase in inflation is likely to be transitory, given the degree of slack in the global economy and anchored inflation expectations. Annual consumer price inflation in member countries of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) increased to 3.3% in April, up from 2.4% in March (Chart 3). Energy prices rose sharply, while food price inflation eased further in April. Core consumer price index inflation (excluding food and energy) increased to 2.4% in April, up from 1.8% the previous month. Headline annual consumer price inflation increased across all advanced economies but remained in negative territory in Japan. With regard to major non-OECD EMEs, in China annual headline inflation edged back more firmly into positive territory after two quarters of near-zero inflation.

Chart 3

OECD consumer price inflation

(year-on-year percentage changes; percentage point contributions)

Sources: OECD and ECB calculations.

Note: The latest observations are for April 2021.

The rising inflation observed this year and its expected gradual deceleration thereafter is also embedded in euro area competitors’ export price projections. Euro area competitors’ export prices (in national currency) are projected to increase significantly in the course of this year. Compared with the March 2021 ECB staff macroeconomic projections, euro area competitors’ export prices were revised upwards for this year amid higher commodity prices and stronger demand. Looking further ahead euro area competitors’ export prices are broadly comparable to previous projections.

2 Financial developments

While the forward curve of the euro overnight index average (EONIA) increased slightly across medium to long-term maturities, the short end of the curve has remained largely the same, suggesting no expectations of an imminent policy rate change in the very near term. Over the review period (11 March to 9 June 2021), euro area sovereign bond yields increased moderately, mainly amid an improved economic outlook in the light of progress in vaccination campaigns across the euro area together with continuing policy support. The more recent widening in sovereign spreads over the overnight index swap (OIS) rate across jurisdictions may be related in part to speculation about an early tapering of purchases under the pandemic emergency purchase programme (PEPP). Equity prices also increased, supported by a strong recovery in corporate earnings growth expectations while discount rates remained relatively low. Mirroring equity prices, euro area corporate bond spreads continued to tighten and stand at levels last observed prior to March 2020. In foreign exchange markets, the nominal effective exchange rate of the euro strengthened slightly.

The EONIA and the benchmark euro short-term rate (€STR) averaged -48 and -57 basis points respectively over the review period.[2] Excess liquidity increased by approximately €516 billion to around €4,207 billion, mainly reflecting asset purchases under the PEPP and the asset purchase programme (APP), as well as the TLTRO III.7 operation take-up of €330.5 billion. These liquidity injections were partially offset by developments in autonomous factors and expiring TLTRO II operations.

While the EONIA forward curve shifted slightly upwards across medium to long-term maturities over the review period, the short end of the curve remained broadly unchanged and continues to indicate no expectations of an imminent change in the deposit facility rate (Chart 4). The short end of the EONIA forward curve is currently almost completely flat, suggesting that financial market participants are not pricing in an imminent rate cut or hike. The 10-year EONIA spot rate rose by 6.2 basis points.

Chart 4

EONIA forward rates

(percentages per annum)

Sources: Refinitiv and ECB calculations.

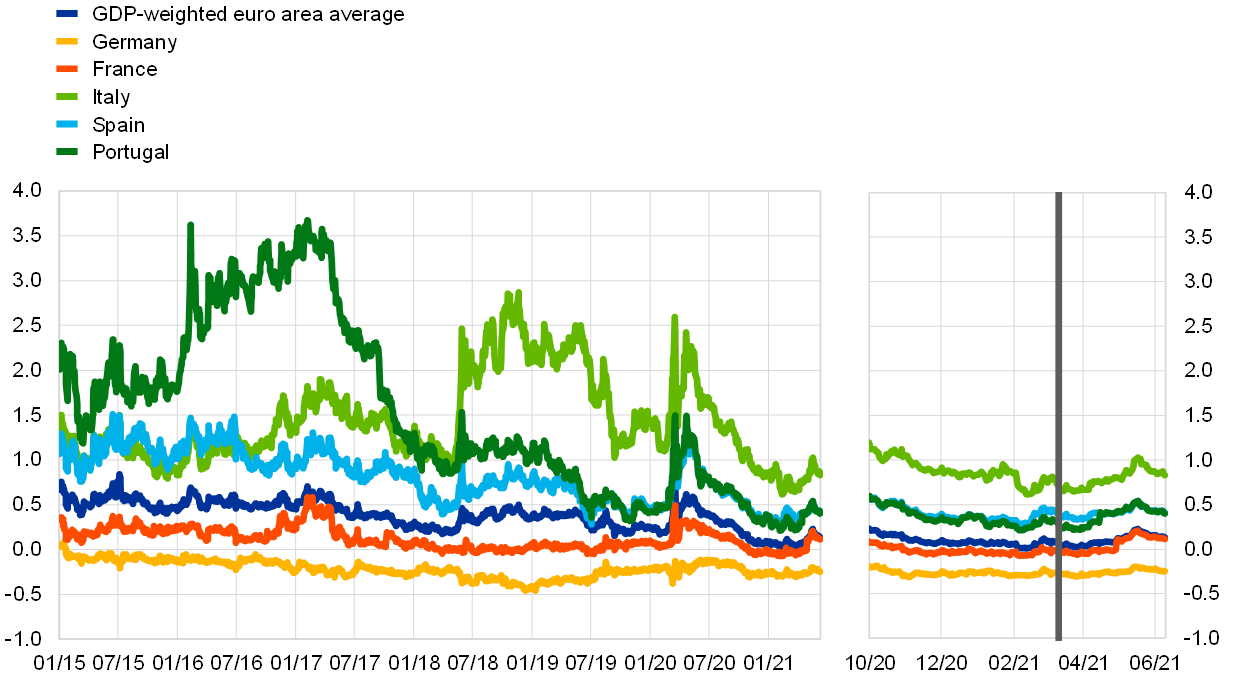

Euro area sovereign bond yields increased somewhat over the review period (Chart 5). Euro area sovereign bond yields rose notably as term premia became less negative. The brightening of the public health situation and a corresponding improvement in market participants’ assessment of the economic outlook contributed to the movement. Specifically, the GDP-weighted euro area ten-year sovereign bond yield increased by 14 basis points to reach 0.13%. At the same time, ten-year sovereign bond yields in the United States and the United Kingdom decreased slightly to stand at 1.49% and 0.73% respectively.

Chart 5

Ten-year sovereign bond yields

(percentages per annum)

Sources: Refinitiv and ECB calculations.

Notes: The vertical grey line denotes the start of the review period on 11 March 2021. The latest observation is for 9 June 2021.

Long-term spreads of euro area sovereign bonds relative to OIS rates increased moderately (Chart 6). While the widening of yield spreads over the review period can partly be attributed to an increase in credit risk premia, more recent gyrations may likewise be related to speculation about adjustments in the pace of PEPP purchases as well as significant sovereign bond supply. Overall, the increase in sovereign spreads has been broad-based across countries, with Italian, Portuguese and French ten-year spreads increasing by 16, 15 and 15 basis points to stand at 0.83%, 0.40% and 0.11% respectively. Over the same period, German and Spanish ten-year spreads increased by 3 and 4 basis points to reach -0.25% and 0.41% respectively.

Chart 6

Ten-year euro area sovereign bond spreads vis-à-vis the OIS rate

(percentage points)

Sources: Refinitiv and ECB calculations.

Notes: The spread is calculated by subtracting the ten-year OIS rate from the ten-year sovereign bond yield. The vertical grey line denotes the start of the review period on 11 March 2021. The latest observation is for 9 June 2021.

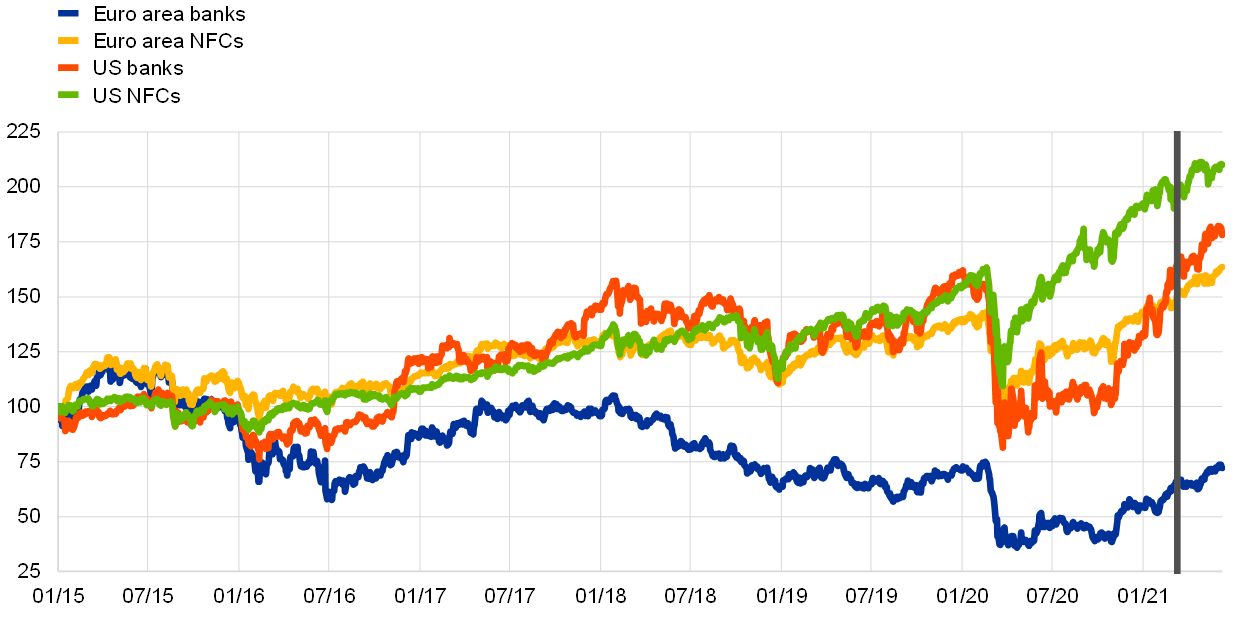

Equity prices increased on both sides of the Atlantic, reaching record highs in the United States, on the back of higher earnings growth expectations and discount rates remaining at relatively low levels (Chart 7). Euro area equity prices rose against the backdrop of persistently low discount rates and especially of a strong recovery in corporate earnings growth expectations. However, equity markets continue to signal an uneven recovery across sectors and countries. At the same time, there are no evident signs of overvaluation or excessive risk taking. Overall, the stock prices of euro area and US non-financial corporations (NFCs) increased by 7.9% and 5.4% respectively, while the equity prices of euro area and US banks rose by 11% and 8.6%.

Chart 7

Euro area and US equity price indices

(index: 1 January 2015 = 100)

Sources: Refinitiv and ECB calculations.

Notes: The vertical grey line denotes the start of the review period on 11 March 2021. The latest observation is for 9 June 2021.

Euro area corporate bond spreads continued to tighten slightly to levels last observed prior to March 2020 (Chart 8). Mirroring the increase in equity prices, euro area corporate bond spreads continued to decline. Over the review period, the investment-grade NFC bond spread and financial sector bond spread (relative to the risk-free rate) narrowed by 8 and 9 basis points respectively, to stand at pre-pandemic levels. Reasons for the continued tightening are likely related to further improvements in the macroeconomic outlook, coupled with the unprecedented policy support and rating agencies’ currently relatively benign view of near-term credit risks. Despite this, pockets of vulnerability continue to exist, and the current level of spreads appears to be predicated on ongoing policy support.

Chart 8

Euro area corporate bond spreads

(basis points)

Sources: Markit iBoxx indices and ECB calculations.

Notes: The spreads are the difference between asset swap rates and the risk-free rate. The indices comprise bonds of different maturities (with at least one year remaining) with an investment-grade rating. The vertical grey line denotes the start of the review period on 11 March 2021. The latest observation is for 9 June 2021.

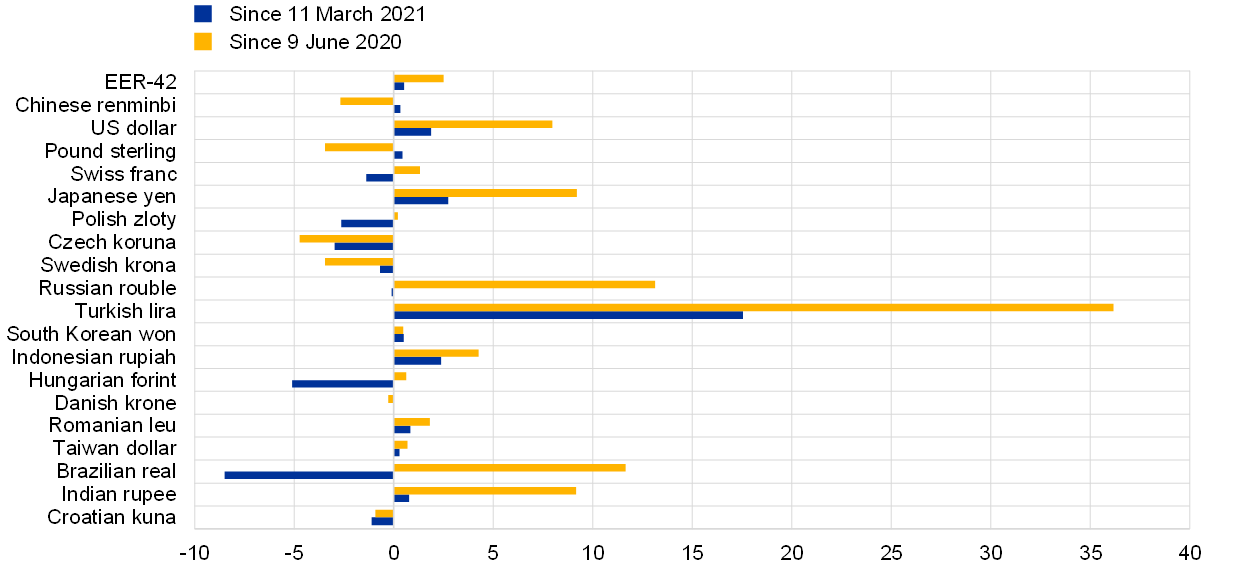

In foreign exchange markets, the euro appreciated slightly in trade-weighted terms (Chart 9) in the context of an improved economic outlook for the euro area. Over the review period, the nominal effective exchange rate of the euro, as measured against the currencies of 42 of the euro area’s most important trading partners, strengthened by 0.5%. The euro appreciated against the US dollar (by 1.9%), reflecting the improved outlook for the euro area economy as the pace of vaccination picked up, coupled with the weakness of the dollar, which declined from the end of March alongside US Treasury yields. The euro also appreciated against the Japanese yen (by 2.7%), the pound sterling (by 0.4%) and the Chinese renminbi (by 0.3%). The euro appreciated strongly (by 17.5%) against the Turkish lira, which experienced broad-based weakness, while depreciating markedly (by 8.5%) against the Brazilian real, which broadly strengthened on the back of rebounding commodity prices. The euro also depreciated against the Swiss franc (by 1.4%) and the currencies of several non-euro area EU Member States, including the Hungarian forint, the Czech koruna and the Polish zloty.

Chart 9

Changes in the exchange rate of the euro vis-à-vis selected currencies

(percentage changes)

Source: ECB.

Notes: EER-42 is the nominal effective exchange rate of the euro against the currencies of 42 of the euro area’s most important trading partners. A positive (negative) change corresponds to an appreciation (depreciation) of the euro. All changes have been calculated using the foreign exchange rates prevailing on 9 June 2021.

3 Economic activity

GDP declined further by 0.3% in the first quarter of 2021 to stand 5.1% below its pre-pandemic level of the fourth quarter of 2019. Domestic demand contributed negatively to growth in the first quarter of 2021, while net trade provided a small positive contribution. Changes in inventories had a strong positive impact on growth. Business and consumer surveys and high-frequency indicators point to a sizeable improvement in activity in the second quarter of this year. Manufacturing production remains robust, supported by solid global demand, although supply-side bottlenecks could pose some headwinds for industrial activity in the near term. At the same time, business surveys indicate a strong recovery in services activity as infection numbers decline, which will allow a gradual normalisation of high-contact activities. Indicators of consumer confidence are strengthening, suggesting a strong rebound in private consumption in the period ahead. Business investment shows resilience, despite weaker corporate balance sheets and the still uncertain economic outlook. Growth is expected to continue to improve strongly in the second half of 2021 as progress in vaccination campaigns should allow a further relaxation of containment measures. Over the medium term, the recovery in the euro area economy is expected to be buoyed by stronger global and domestic demand, as well as by continued support from both monetary policy and fiscal policy.

This assessment is broadly reflected in the baseline scenario of the June 2021 Eurosystem staff macroeconomic projections for the euro area. These projections foresee annual real GDP growth at 4.6% in 2021, 4.7% in 2022 and 2.1% in 2023. Compared with the March 2021 ECB staff macroeconomic projections, the outlook for economic activity has been revised up for 2021 and 2022, while it is unchanged for 2023.

Overall, the risks surrounding the euro area growth outlook are assessed as broadly balanced. On the one hand, an even stronger recovery could be predicated on brighter prospects for global demand and a faster-than-anticipated reduction in household savings once social and travel restrictions have been lifted. On the other hand, the ongoing pandemic, including the spread of virus mutations, and its implications for economic and financial conditions continue to be sources of downside risk.

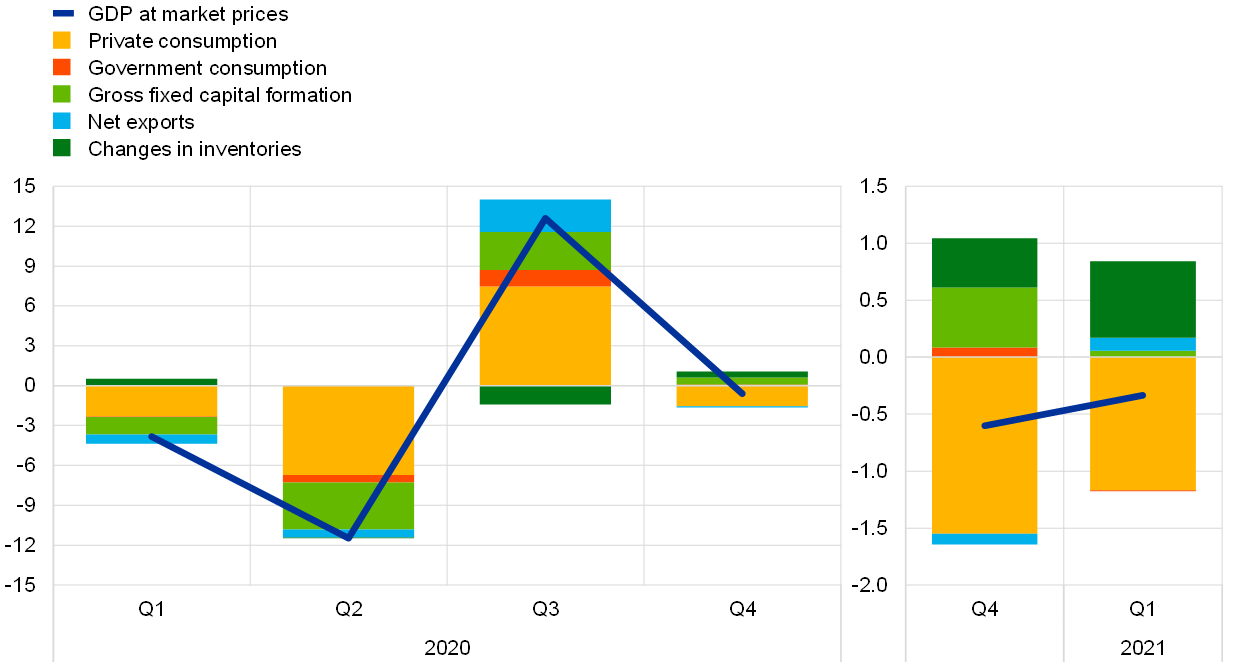

Following a renewed contraction in output in the first quarter of 2021, economic activity in the euro area is set for a rebound in the second quarter. Real GDP declined further by 0.3% quarter on quarter in the first quarter of 2021, following a fall of 0.6% in the fourth quarter of last year (Chart 10). The decline was somewhat lower than the 0.4% contraction foreseen in the March 2021 ECB staff macroeconomic projections. The fall in output in the first quarter was due to domestic demand, particularly private consumption, while changes in inventories had a strong positive impact with a further small positive contribution from net trade. On the production side, developments in the first quarter continued to vary significantly across sectors. While value added in the services sector declined further, output in the industrial sector (excluding construction) increased again.

Chart 10

Euro area real GDP and its components

(quarter-on-quarter percentage changes; quarter-on-quarter percentage point contributions)

Source: Eurostat.

The euro area labour market continues to benefit from significant policy support mitigating the impact of the pandemic. According to the preliminary flash data release, employment declined by 0.3% quarter on quarter in the first quarter of 2021, following an increase of 0.3% in the fourth quarter of 2020 (Chart 11). The unemployment rate in that quarter consequently increased to 8.2% from 8.0% in the previous quarter. Employment in the first quarter of 2021 was 2.2% below the level recorded in the fourth quarter of 2019 prior to the outbreak of the pandemic. Hours worked continue to play an important role in the adjustment of the euro area labour markets and policy responses to the challenges posed by the pandemic. Total hours worked declined by 1.5% quarter on quarter in the fourth quarter of 2020 – the last available data point – following an increase of 14.7% in the third quarter, remaining 6.4% below the level seen at end-2019. Meanwhile, the unemployment rate declined to 8.0% in April 2021 from a level of 8.1% in the previous month and below the pandemic crisis peak of 8.7% recorded in August 2020. Nevertheless, the unemployment rate exceeds the pre-pandemic level of 7.3% recorded in February 2020. Workers covered by job retention schemes were estimated to account for around 6% of the labour force in March 2021, down from almost 20% in April 2020. However, the number of workers covered by such schemes has been rising since October 2020 as a result of renewed containment measures in some countries. Looking ahead, the substantial numbers of workers who are still covered by job retention schemes pose upward risks to the unemployment rate.

Chart 11

Euro area employment, the PMI assessment of employment and the unemployment rate

(left-hand scale: quarter-on-quarter percentage changes, diffusion index; right-hand scale: percentages of the labour force)

Sources: Eurostat, Markit and ECB calculations.

Notes: The PMI employment index is shown at a monthly frequency; employment and unemployment are shown at a quarterly frequency. The PMI is expressed as a deviation from 50 divided by 10. The latest observations are for the first quarter of 2021 for employment, May 2021 for the PMI and April 2021 for the unemployment rate.

Despite improved short-term labour market indicators, households’ unemployment expectations remain elevated. In May 2021 the composite PMI employment indicator for the euro area continued to increase further in expansionary territory. The indicator has pointed to expanding employment since February of this year. More recently, the expectations of households about future unemployment conditions have improved. While unemployment expectations have declined since March 2021, they remain significantly above pre-pandemic levels.

Following a fall in private consumption in the first quarter, consumers have gradually become more optimistic, although their financial situation remains fragile. After a weak first quarter, when private consumption fell by 2.3%, consumer spending is expected to recover in the course of the second quarter even though this is not yet fully evident in a number of indicators released at the beginning of that quarter. In April 2021 the volume of retail trade shrank by 3.1% month on month, nonetheless standing 0.3% above its average level in the first quarter. Car registrations declined slightly in April (by 0.4% month on month), to more than 20% below their February 2020 levels. On the positive side, consumer confidence returned to its pre-pandemic level in May (-5.1 compared with ‑8.1 in April and -10.8 in March). The latest increases are largely attributable to households’ improving expectations about the general economic situation, while their assessment of their current personal financial situation is still well below pre-crisis levels. As the economy recovers, labour income should increasingly support household income, reducing its dependence on fiscal support. In April consumers also started saving less in bank deposits, in line with a gradual recovery of private consumption (see also Section 5). The European Commission’s Consumer Survey suggests that consumer spending will continue to rise over the next 12 months, while showing no signs of exuberance.

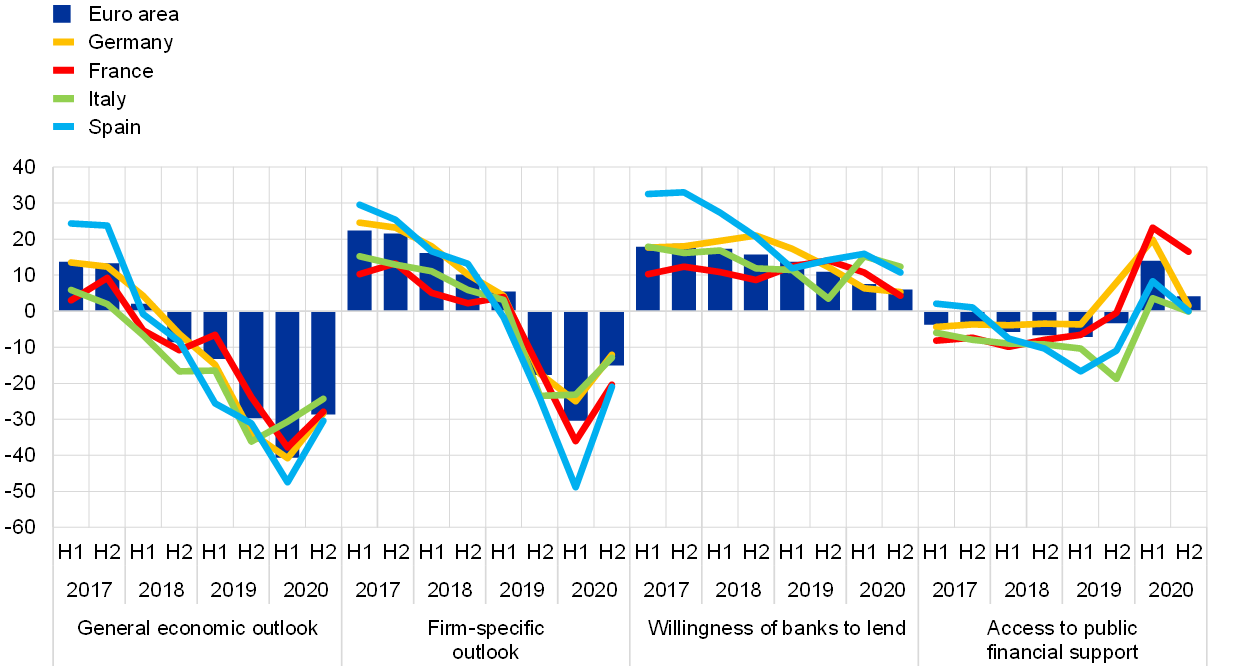

Corporate (non-construction) investment declined slightly in the first quarter of 2021, but a strong rebound is expected in the second quarter and for the remainder of the year. Supply-chain bottlenecks and a tightening of containment measures in some euro area countries contributed to a 0.4% quarter-on-quarter contraction in non-construction investment in the first quarter of the year, following an elevated quarterly growth rate in the last quarter of 2020. The first quarter decline reflects a strong reduction in investment in motor vehicles and a marked reversal of the strong investment in intellectual property products seen in the last quarter of 2020, which more than offset the strong growth in investment in other machinery. In the second quarter of 2021, short-term indicators suggest a marked and broadly-based strengthening across countries. In particular, survey data into May show a strong increase in confidence in the capital goods sector, reflecting buoyant demand and strong export orders following record-high production expectations in April. On the supply side, capacity utilisation in the capital goods sector was also well above the pre-pandemic level at the start of the second quarter and reported limits to production from shortages of equipment have increased sharply. For the year as a whole, survey data support the view of stronger business investment growth ahead. The latest Survey on the Access to Finance of Enterprises (SAFE[3]), conducted in March and April 2021, points to a stabilisation in firms’ fixed investment decisions despite still elevated uncertainty and weaker corporate balance sheets.[4] The April 2021 bi-annual European Commission Investment Survey foresees industrial investment growing by 7% in 2021 – around twice the rate expected in the November 2020 survey ‒ and mainly for extension and replacement purposes, rather than to rationalise production.

Housing investment increased further in the first quarter of 2021 and its overall positive trend is expected to continue going forward. Housing investment increased in the first quarter, rising by 0.5% quarter on quarter, falling short of its pre-crisis level in the last quarter of 2019 by 1.2%. Looking ahead, housing investment in the euro area is expected to continue on a positive trend, although the strength of the upward movement in the short term is likely to be limited by supply constraints. On the demand side, the European Commission’s survey data show that consumers’ short-term intentions to buy or build a house have reached their highest level since early 2003, while their intentions to renovate their homes reached their highest level on record. On the supply side, confidence in the construction sector continued to improve in April and May. The strong increase in companies’ assessments of the overall level of orders signals a robust demand for housing. At the same time, however, supply concerns have intensified. According to the European Commission’s survey data, construction companies faced historically high production limits in the first two months of the second quarter owing to scarcity of materials and labour shortages. Supply constraints are also reflected in the PMI surveys for the construction sector, which suggest that supplier delivery times rose markedly on average in April and May, compared with the first quarter of 2021. Moreover, firms’ business expectations for the coming year fell somewhat but remained in expansionary territory.

Euro area trade growth decreased in the first quarter of 2021 and resulted in a slightly positive net trade contribution to GDP. After sustained growth rates in the second half of 2020, the recovery of euro area exports slowed down in the first quarter of 2021 (+1.0% quarter on quarter). Disruptions as a result of Brexit together with shipping and input-related constraints exerted a drag. Nominal trade in goods data reveal that trade with the United Kingdom only partially recovered from the Brexit-related slump of January 2021, with nominal imports particularly affected and standing at 75% of their December 2020 level in March 2021. As regards other destinations, positive contributions to the growth of extra-euro area goods export volumes came from China. From a sectoral perspective, a slowdown is apparent across all categories except capital goods. Long delivery times and increasing freight rates, along with a shortage of intermediate inputs (such as chemicals, wood, plastic, metals and semiconductors), put a strain on the growth of euro area manufacturing exports (see Box 6). However, order-based forward-looking indicators signal a strong momentum ahead for goods exports. Trade in services shows some signs of improvement with the upcoming summer season and expectations for mobility easing that would support travel services exports. Imports increased broadly at the same pace as exports in the first quarter of 2021 (+0.9% quarter on quarter) and are expected to be sustained by the recovery of domestic demand in the coming quarters.

Incoming information points to a sizeable improvement in euro area activity in the second quarter of 2021. Survey data have improved, consistent with renewed robust growth in the second quarter of 2021. The recent strengthening has been broad-based across sectors as well as across countries. The composite output PMI, which rose from 48.1 in the fourth quarter of 2020 to 49.9 in the first quarter of 2021, has recently increased further, averaging 55.4 over April and May. This improvement reflects developments in both manufacturing and services ‒ both sectors are now generating survey results consistent with growth. Progress with vaccination campaigns appears to have spurred confidence further, particularly in services. Confidence has risen across all services sub-sectors, although it remains significantly below pre-pandemic levels in high-contact activities. The increase in confidence bodes well for the expected recovery of services, but the very large gap in comparison with pre-crisis levels of activity in high-contact sub-sectors suggests that they still suffer from ample spare capacity.

The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic has weakened growth in recent months, yet recovery is imminent, and a strong rebound is expected as of the second half of 2021. Notwithstanding an extension of stringent containment measures for much of the first half of 2021, learning effects, resilient manufacturing output and foreign demand, as well as support from monetary and fiscal policy, have contained output losses to a greater extent than in the first wave of the pandemic despite supply bottlenecks hampering production in some sectors. In the near term, an accelerated roll-out of vaccinations and concomitant declines in infection rates should allow a faster than previously expected unwinding of containment measures from their more stringent levels in the first half of 2021. This is reflected in the June 2021 Eurosystem staff macroeconomic projections for the euro area, which foresee annual real GDP growth of 4.6% in 2021, 4.7% in 2022 and 2.1% in 2023 (Chart 12). Euro area activity is projected to return to growth in the second quarter of 2021 and, driven by a sharp rebound in private consumption and an easing of current supply chain disruptions, to pick up strongly in the second half of the year, allowing real GDP to exceed its pre-crisis level as of the first quarter of 2022.[5]

Chart 12

Euro area real GDP (including projections)

(quarter-on-quarter percentage changes)

Sources: Eurostat and the article entitled “Eurosystem staff macroeconomic projections for the euro area, June 2021”, published on the ECB’s website on 10 June 2021.

Notes: In view of the unprecedented volatility of real GDP in 2020, this chart uses a different scale from 2020 onwards. The vertical line indicates the start of the projection horizon. The chart does not show ranges around the projections, reflecting the fact that, in the present circumstances, the standard computation method for those ranges (which is based on historical projection errors) would not provide a reliable indication of the unprecedented uncertainty surrounding current projections.

4 Prices and costs

According to Eurostat’s flash release, annual euro area inflation rose to 2.0% in May 2021, up from 1.3% in March and 1.6% in April. That rise was mainly due to a strong increase in energy price inflation (reflecting sizeable upward base effects, as well as month-on-month increases), but also, to a lesser extent, a slight increase in non‑energy industrial goods inflation. Headline inflation is likely to increase further towards the autumn, mainly reflecting the reversal of the temporary VAT cut in Germany. Inflation is expected to decline again at the start of next year as the impact of temporary factors fades and global energy prices moderate. Underlying price pressures are expected to increase somewhat this year, owing to temporary supply constraints and the recovery in domestic demand. Nevertheless, price pressures are expected to remain subdued overall, partly reflecting low wage pressures, in the context of significant economic slack and the effects of the recent appreciation of euro exchange rates. When the impact of the pandemic fades, the unwinding of the high levels of slack will, supported by accommodative monetary and fiscal policies, contribute to a gradual increase in underlying inflation over the medium term. Survey and market-based indicators of longer-term inflation expectations remain at subdued levels, although market-based indicators have continued to increase.

This assessment is broadly reflected in the baseline scenario of the June 2021 Eurosystem staff macroeconomic projections for the euro area, which foresees annual HICP inflation of 1.9% in 2021, 1.5% in 2022 and 1.4% in 2023. Compared with the March 2021 ECB staff macroeconomic projections, the outlook for inflation has been revised upwards for 2021 and 2022, largely owing to temporary factors and increases in energy price inflation. It is unchanged for 2023, when the expected increase in underlying inflation is largely counterbalanced by an expected decline in energy price inflation. HICP inflation excluding energy and food is projected to stand at 1.1% in 2021, 1.3% in 2022 and 1.4% in 2023, with upward revisions being seen at all projection horizons relative to the March 2021 projection exercise.

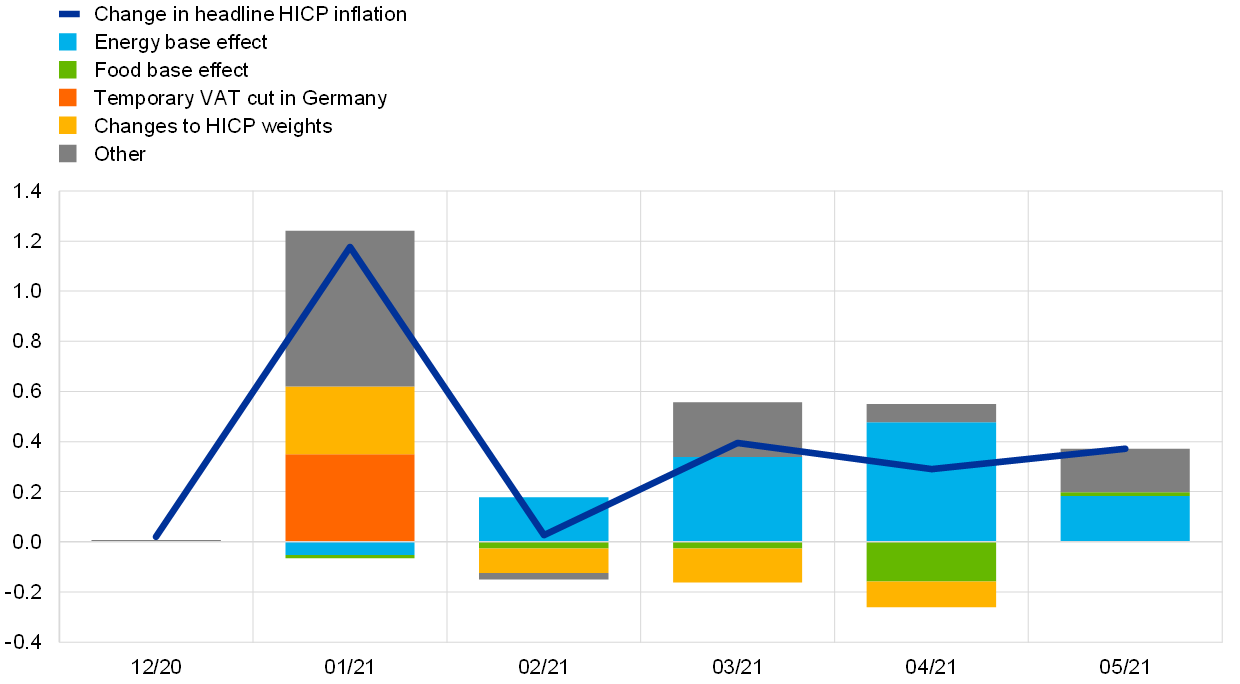

According to Eurostat’s flash estimate, annual HICP inflation rose further in May. It stood at 2.0% in that month, up from 1.6% in April and 1.3% in March, mainly reflecting the further strengthening of energy inflation (Chart 13). Upward base effects associated with the strong declines observed in oil and energy prices in spring 2020 accounted for around half of the total increase seen in headline inflation between December 2020 and May 2021.[6]

Chart 13

Headline inflation and its components

(annual percentage changes; percentage point contributions)

Sources: Eurostat and ECB calculations.

Note: The latest observations are for May 2021 (flash estimate).

Developments in headline inflation in recent months also reflect the influence of other temporary factors. For instance, the changes to HICP weights at the start of this year resulted in strong increases in inflation in January, but that effect has more or less unwound in subsequent months (with April being the most recent month for which that calculation can be carried out).[7] Similarly, the temporary surge in unprocessed food prices in April 2020 resulted in a downward base effect in April 2021, which offset some of the upward pressure from energy-related base effects (Chart 14). Calendar effects have also had an impact on inflation rates in recent months. For instance, services inflation rose to 1.1% in May, up from 0.9% in the previous month, partly on account of the timing of Easter and other holidays in that period. At the same time, changes in the timing and scope of sales periods in shops had a strong upward impact on non-energy industrial goods (NEIG) inflation in January and February, but that effect has since unwound, and the figure of 0.7% that was recorded in May – slightly above the long-term average of 0.6% – may be a better indication of the extent to which input costs have increased along the supply chain in recent months.

Chart 14

Contributions of base effects and other temporary factors to monthly changes in annual HICP inflation

(percentage point changes and contributions)

Sources: Eurostat, Deutsche Bundesbank and ECB calculations.

Notes: The contribution made by the temporary VAT cut in Germany is based on estimates provided in the Deutsche Bundesbank’s November 2020 Monthly Report. The contribution made by changes to HICP weights cannot be calculated for May 2021 (as the necessary data are not yet available) and is therefore netted out in the “other” component. The latest observations are for May 2021 (based on flash estimate).

Price imputations imply continued uncertainty surrounding the signal for underlying price pressures. According to provisional data from Eurostat, imputation shares declined only moderately between January and May, falling from 13% to 10% for the HICP and from 18% to 13% for the HICP excluding energy and food. This is mainly explained by the imputation share for services, which has been fairly stable at around one-fifth since November of last year as a result of the large shares for recreational and travel-related services. In contrast, the imputation share for NEIG items has declined considerably, falling from 17% in January to just 6% in May. However, given the greater weight attributed to services, these developments continue to imply a high degree of uncertainty surrounding the signal for underlying price pressures.

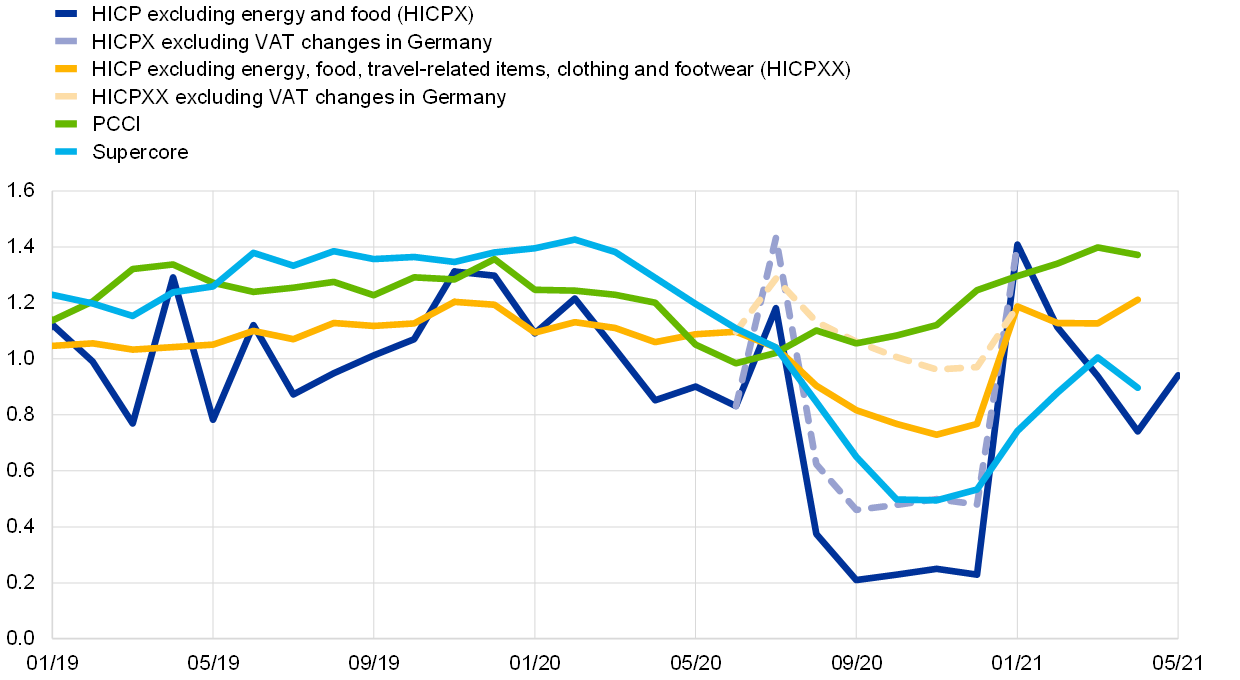

Measures of underlying inflation do not provide a broad-based signal pointing to a sustained rise in inflationary pressures (Chart 15). After increasing strongly in January, HICPX inflation declined considerably, falling to 0.9% in March and 0.7% in April, before rising to 0.9% in May. Those patterns in the first few months of 2021 were mainly attributable to developments in clothing, footwear and travel‑related services (including package holidays, accommodation services and air passenger transport).[8] HICPXX inflation, which excludes those clothing and travel‑related items, has been more stable than HICPX inflation and stood at 1.2% in April (the latest figure available). Looking at other measures of underlying inflation, the Persistent and Common Component of Inflation (PCCI) stood at around 1.4% in April, broadly unchanged from March, whereas the Supercore measure declined moderately (falling from 1.0% to 0.9%) over the same period.

Chart 15

Measures of underlying inflation

(annual percentage changes)

Sources: Eurostat and ECB calculations.

Note: The latest observations relate to May 2021 for the HICPX indicator (flash estimate) and April 2021 for the rest.

Pipeline price pressures for non-energy industrial consumer goods continue to increase considerably – albeit mainly at earlier stages of the pricing chain thus far. In this respect, producer price inflation for intermediate goods has risen further, standing at 6.9% in April, 2.5 percentage points higher than in March and 4.4 percentage points higher than in February. Likewise, import price inflation for intermediate goods has increased substantially, standing at 7.1% in April, up from 4.6% in March and 1.5% in February. These developments probably reflect upward pressure from shipping costs, supply bottlenecks and high levels of commodity price inflation. These pressures are less visible at later stages of the pricing chain, in line with past experience of substantial buffering along the pricing chain. However, at 0.9% in March and 1.0% in April, domestic producer price inflation for non-food consumer goods has increased and moved above its long-term average of 0.6%. The impact that domestic producer prices are having on consumer goods inflation is, in part, being contained by the negative annual growth rates of import prices for non‑food consumer goods (-0.8% in April, down from -0.5% in March), which remain subdued owing to the impact of past exchange rate appreciation.[9]

Growth in negotiated wages weakened substantially in the first quarter of 2021 (Chart 16). The 1.4% year-on-year growth seen in that quarter represents a substantial moderation relative to the rates recorded in the fourth quarter of 2020 (2.0%) and across 2020 as a whole (1.8%). As anticipated, COVID-19’s impact on negotiated wages did not become visible until wage agreements concluded before the onset of the pandemic had expired and new agreements were either delayed or concluded using lower wage rates.[10] Given the possible coverage and timing issues, the negotiated wage growth seen in the first quarter may not necessarily be indicative of actual pay growth. Indicators of actual wage growth, such as compensation per employee (CPE) or compensation per hour (CPH), continue to be strongly affected by job retention and temporary lay-off schemes, which have an impact on pay and hours worked and tend to depress CPE and push up CPH. In the first quarter of 2021, the difference between the growth rates of those two indicators declined but remained significant. While annual CPE growth rose to 1.9% in the first quarter of this year, up from 1.0% in the fourth quarter of 2020, annual CPH growth fell from 5.2% to 3.2% over the same period.

Chart 16

Contributions made by components of compensation per employee

(annual percentage changes; percentage point contributions)

Sources: Eurostat and ECB calculations.

Note: The latest observations relate to the first quarter of 2021.

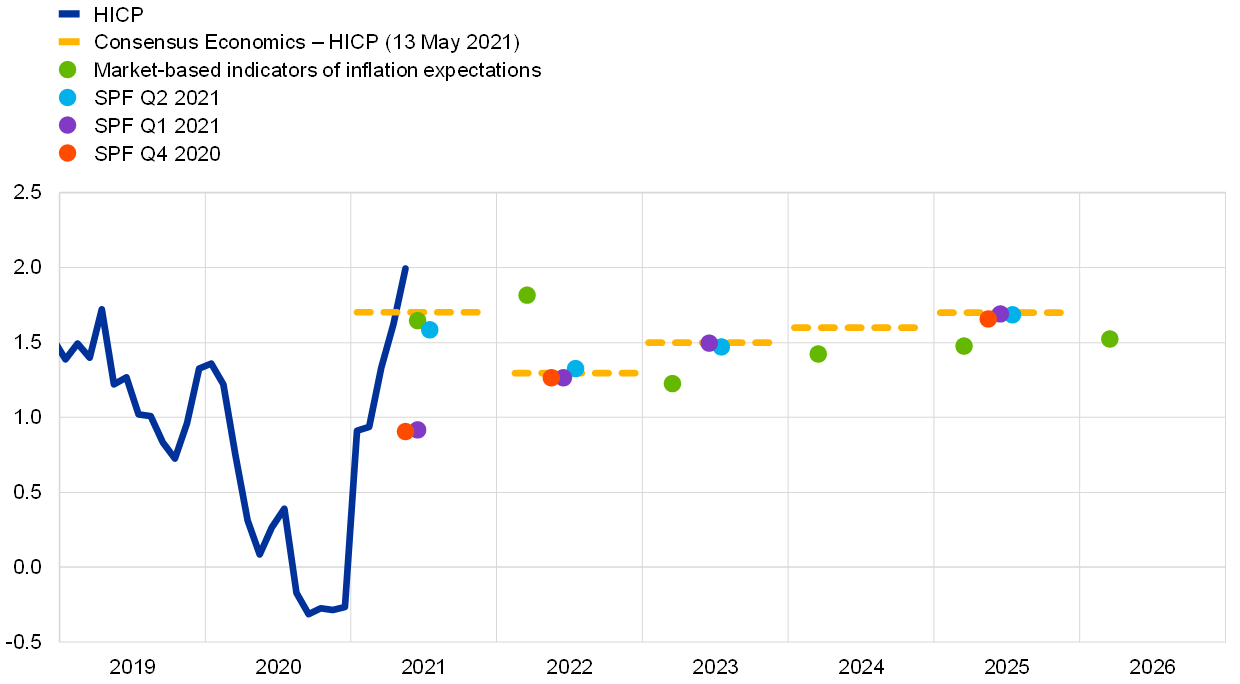

Market-based indicators of inflation compensation have continued to rise. Both shorter and longer-term market-based indicators of inflation compensation remain on an upward path, against the backdrop of improvements in risk sentiment and expectations regarding the unwinding of pent-up consumer spending, as well as the fiscal stimuli deployed around the globe. Long-term inflation risk premia are estimated to have increased considerably over the past few months, thereby accounting for the bulk of the overall increase in long-term inflation compensation. Improvements in expectations have been stronger at shorter horizons, resulting in the flattening of the inflation forward curve (Chart 17). The most prominent forward inflation-linked swap rate, the five-year inflation-linked swap rate five years ahead, stood at 1.56% on 9 June, up from 1.52% on 20 April. As regards survey-based measures, data from the ECB’s Survey of Professional Forecasters (SPF) and Consensus Economics indicate that average longer‑term inflation expectations for 2025 remained unchanged at 1.7% in April.

Chart 17

Survey and market-based indicators of inflation expectations

(annual percentage changes)

Sources: Eurostat, Thomson Reuters, Consensus Economics, ECB (SPF) and ECB calculations.

Notes: The SPF for the second quarter of 2021 was conducted between 31 March and 12 April 2021. The market-implied curve is based on the one-year spot inflation rate and the one-year forward rate one year ahead, the one-year forward rate two years ahead, the one-year forward rate three years ahead and the one-year forward rate four years ahead. The latest observations for market-based indicators of inflation compensation relate to 9 June 2021.

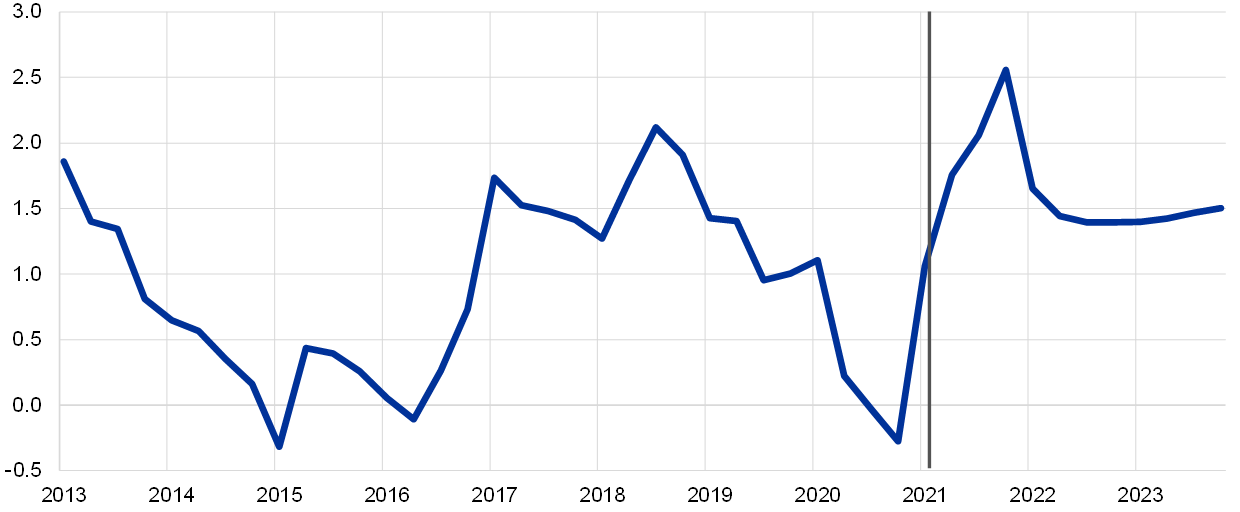

The June 2021 Eurosystem staff macroeconomic projections foresee inflation rising substantially in the course of 2021, before falling back at the beginning of 2022 and remaining broadly flat until the end of 2023. Annual HICP inflation is projected to average 1.9% in 2021, peaking at 2.6% in the fourth quarter, before averaging 1.5% and 1.4% in 2022 and 2023 respectively. The strong growth projected for 2021 reflects upward pressures from a number of temporary factors, including the reversal of the German VAT cut, a strong rebound in energy inflation (due to upward base effects) and an increase in input costs on account of supply constraints. Once the impact of those temporary effects has faded, HICP inflation is expected to be broadly flat in 2022 and 2023. The projected economic recovery and decreases in slack are expected to lead to a gradual increase in HICP inflation excluding energy and food, which is forecast to rise to 1.4% in 2023, up from 1.1% in 2021. Meanwhile, HICP food inflation is also projected to increase slightly over the projection horizon. However, the upward pressures that those two components exert on headline inflation are expected to be broadly offset in 2022 and 2023 by projected declines in energy inflation, given the downward-sloping profile of the oil price futures curve.

Chart 18

Euro area HICP inflation (including projections)

(annual percentage changes)

Sources: Eurostat and the article entitled “Eurosystem staff macroeconomic projections for the euro area, June 2021”, published on the ECB’s website on 10 June 2021.

Notes: The vertical line indicates the start of the projection horizon. The latest observations are for the first quarter of 2021 (data) and the fourth quarter of 2023 (projections). The cut-off date for data included in the projections was 26 May 2021 (and 18 May 2021 for assumptions).

5 Money and credit

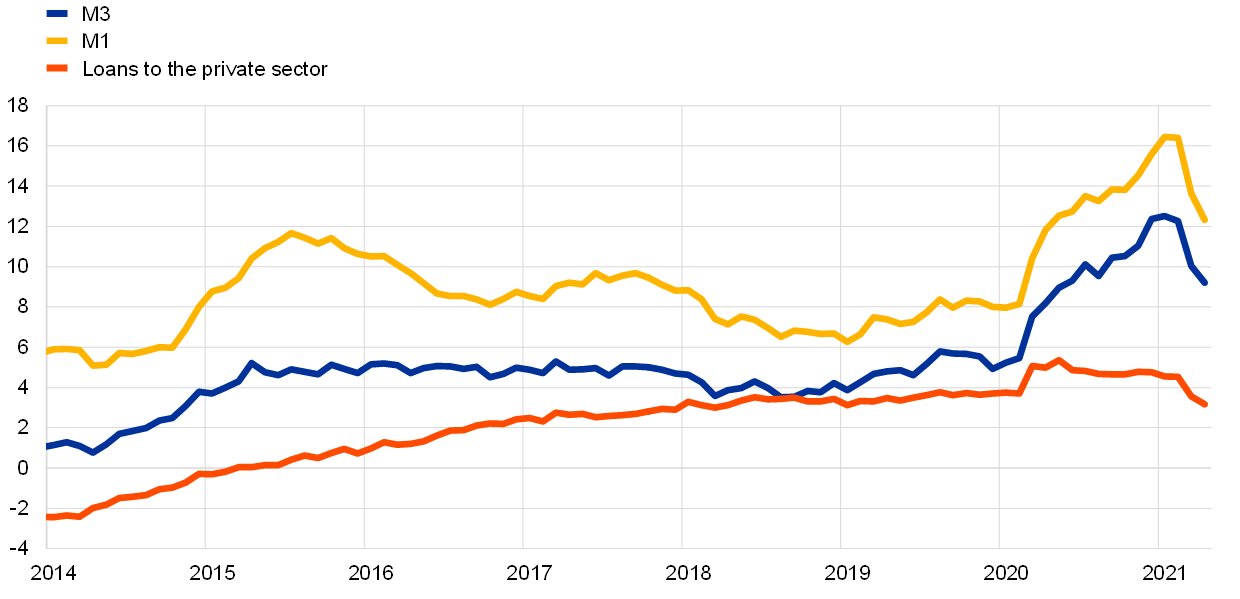

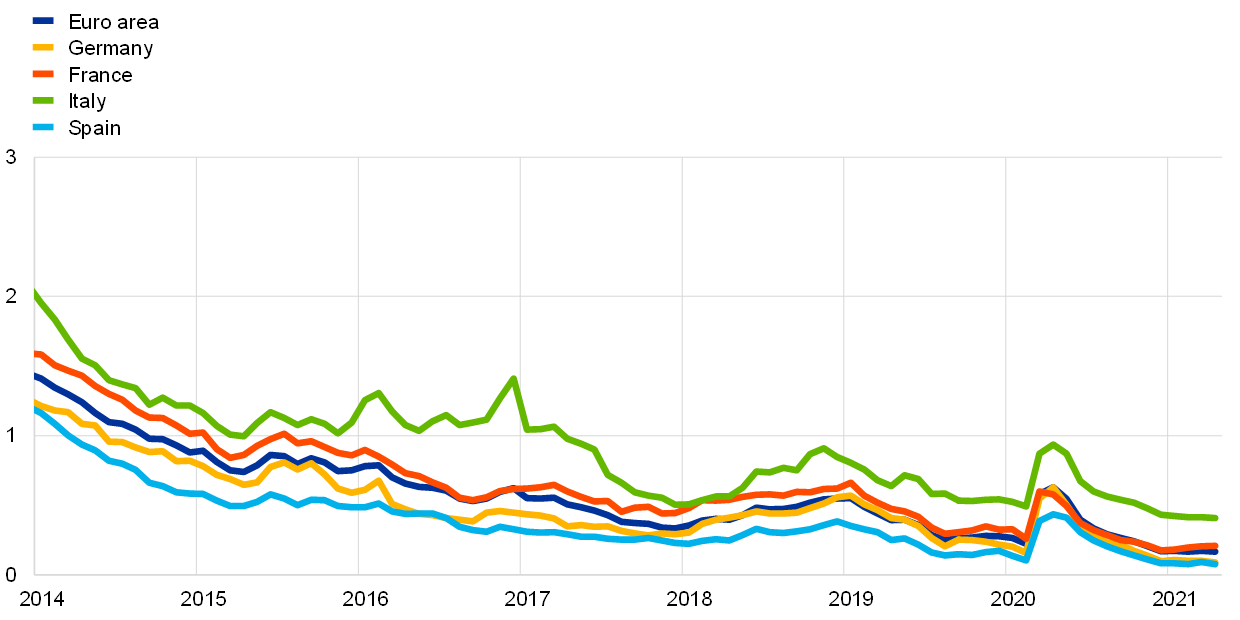

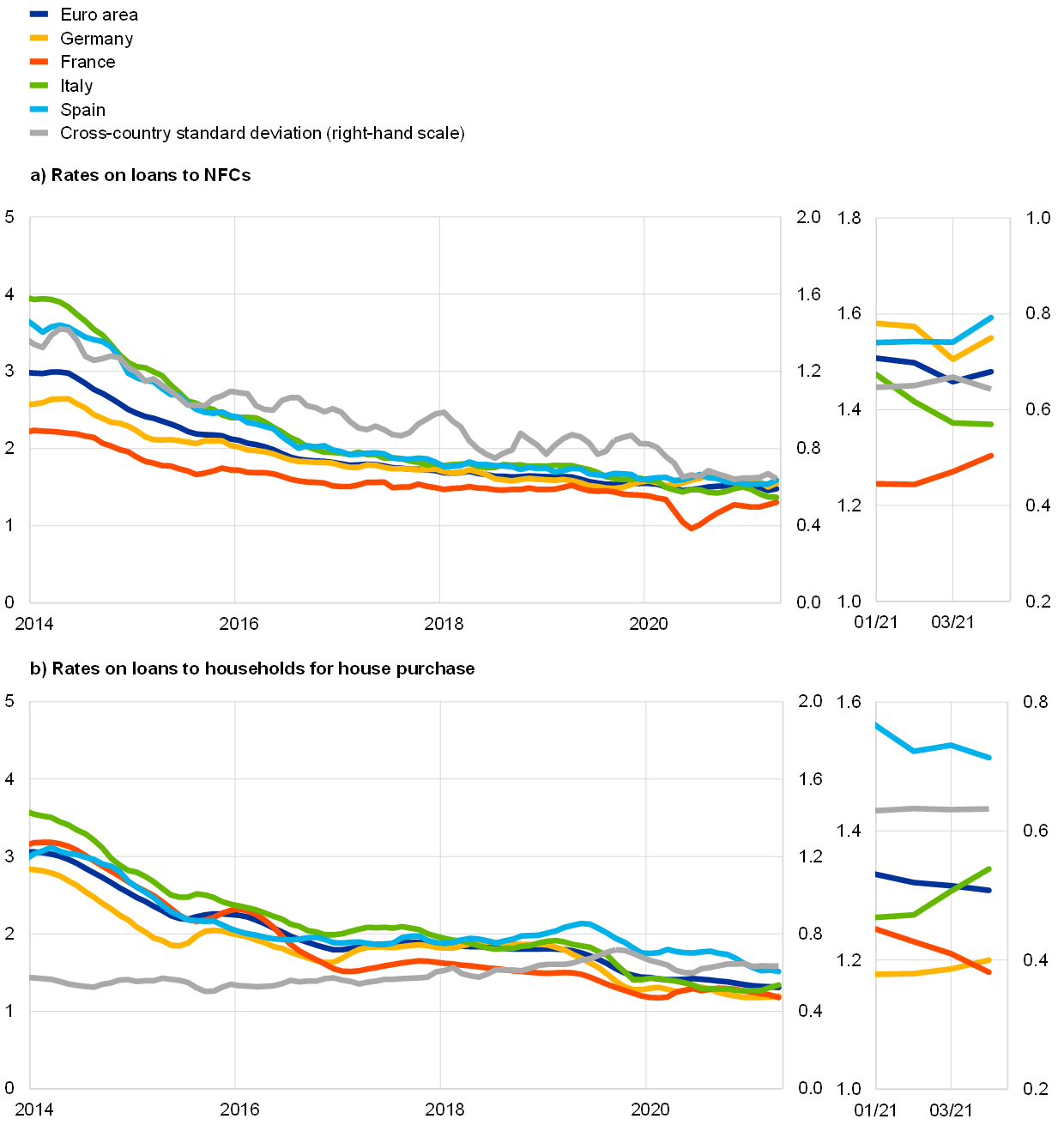

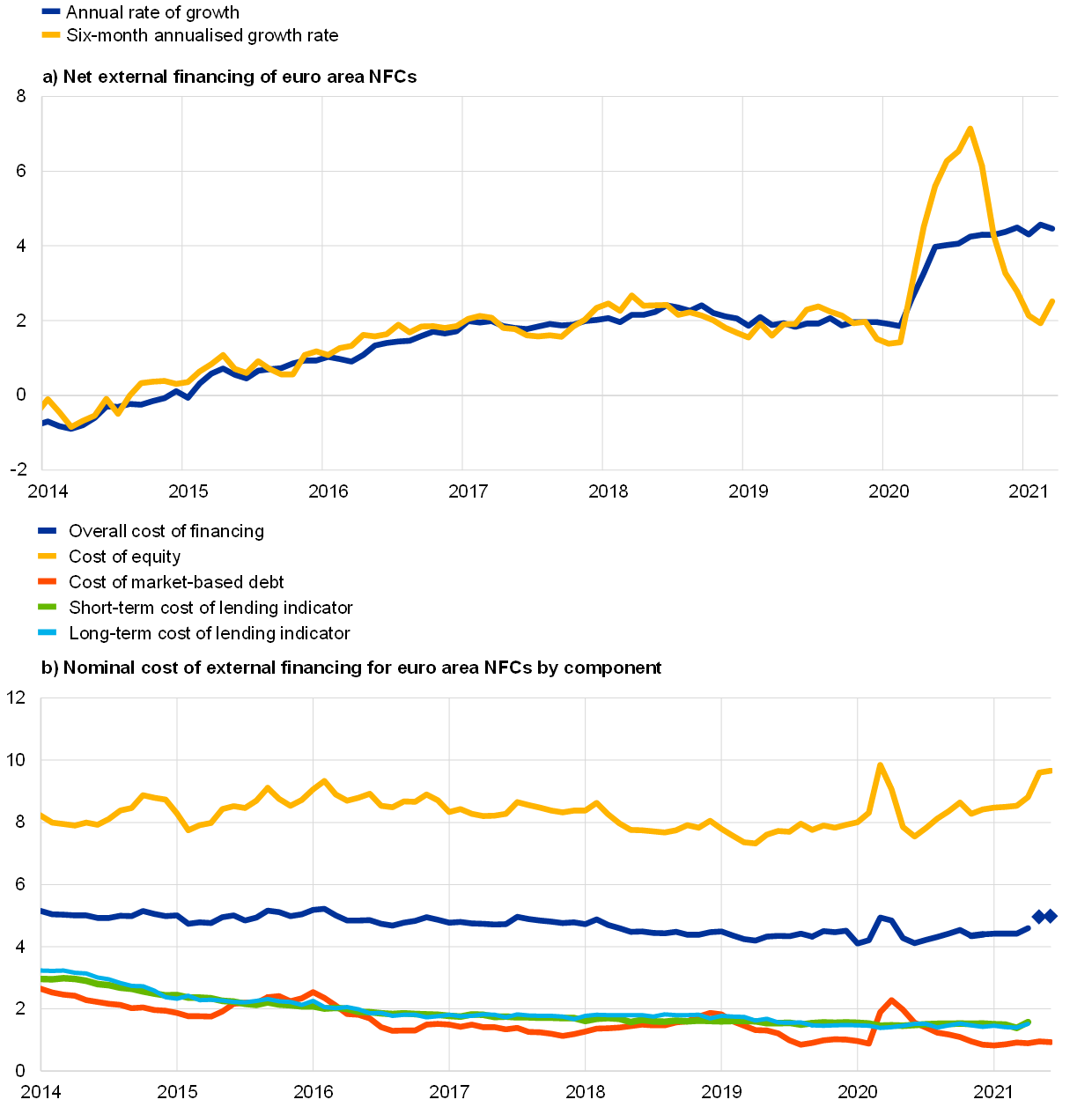

Money creation in the euro area moderated in April 2021, showing some initial signs of normalisation following the significant monetary expansion associated with the coronavirus (COVID-19) crisis. Domestic credit remained the dominant source of money creation, with Eurosystem asset purchases being the most prominent contributor. While the sizeable and timely measures implemented by monetary, fiscal and supervisory authorities continued to support the flow of credit to the euro area economy, growth in loans to the private sector moderated and returned to pre‑pandemic levels, driven by loans to firms. The total volume of external financing for firms rebounded in the first quarter of 2021. Meanwhile, the overall cost of firms’ external financing rose slightly in the first four months of the year, mainly on account of increases in the cost of equity, with the cost of market-based debt and bank lending also increasing marginally.

Broad money growth moderated in April 2021. The annual growth rate of M3 fell to 9.2% in April, down from 10.0% in March (Chart 19), on account of a relatively small monthly inflow and moderation in the growth of overnight deposits. In addition to a strongly negative base effect as the large inflows seen in the initial phase of the pandemic dropped out of the annual growth figures, the fall in M3 growth also reflected smaller inflows for households’ deposits and outflows for firms’ deposits. That decline in households’ accumulation of deposits coincided with an upturn in consumer confidence and supports expectations of an increase in consumer spending. Although the shorter-term dynamics of broad money moderated further, the pace of money creation remained high on the back of the support provided by monetary, fiscal and prudential policies. On the components side, the main driver of M3 growth was the narrow aggregate M1, which includes the most liquid components of M3. The annual growth rate of M1 fell to 12.3% in April, down from 13.6% in March, mainly as a result of developments in deposits held by firms and households. Other short‑term deposits and marketable instruments continued to make a limited contribution to annual M3 growth, reflecting the low level of interest rates and investors’ search for yield.

Chart 19

M3, M1 and loans to the private sector

(annual percentage changes; adjusted for seasonal and calendar effects)

Source: ECB.

Notes: Loans are adjusted for loan sales, securitisation and notional cash pooling. The latest observations are for April 2021.