** Please note that these remarks relate to the ECB’s activities in 2021 and were finalised before the Russian invasion of Ukraine. The ECB stands ready to take whatever action is needed to safeguard financial stability and fulfil its mandate to ensure price stability. **

2021 was the year in which the euro area moved onto a firmer path of recovery from the pandemic emergency. The economy rebounded strongly, with real GDP growing by 5.3%, although growth slowed at the end of the year as the Omicron wave of the coronavirus (COVID-19) led to new restrictions being introduced. The recovery proved job-rich too, with the unemployment rate falling to a record low by year-end.

But the recovery was marked by frictions as the economy rapidly reopened. Though the euro area began 2021 with very low inflation, pandemic-induced supply constraints, a rebound in global demand and surging energy prices meant that inflation increased sharply. Annual headline inflation was 2.6% on average in 2021, compared with just 0.3% in 2020.

The ECB concluded its monetary policy strategy review in 2021. This updated our strategy to address new challenges and provided us with a playbook for managing this complex situation. The Governing Council adopted an inflation target of 2% over the medium term, which is simple and easily understood. It is symmetric, with deviations from the target on both sides seen as equally undesirable. And it is solid, having been agreed by the entire Governing Council.

The Governing Council also agreed on how the ECB would pursue its commitment to symmetry. In particular, when the economy is close to the effective lower bound on policy rates, this requires especially forceful or persistent monetary policy measures to avoid negative deviations from the inflation target becoming entrenched. This new strategy was reflected in our recalibrated forward guidance on interest rates and oriented our policy response to economic developments in the second half of the year.

While the recovery was fragile and inflation subdued, we provided ample monetary support to bring inflation back closer to our target. As inflation rose, we remained patient and persistent in our policy course to avoid tightening prematurely in response to supply-driven shocks. We adjusted the pace of net asset purchases under the pandemic emergency purchase programme (PEPP) in line with the evolving outlook and our assessment of financing conditions.

By December, the Governing Council judged that the progress on economic recovery and towards our medium-term inflation target permitted a step-by-step reduction in the pace of asset purchases over the following quarters. It announced that net asset purchases under the PEPP would end in March 2022, and that its other asset purchase programmes would be gradually scaled back.

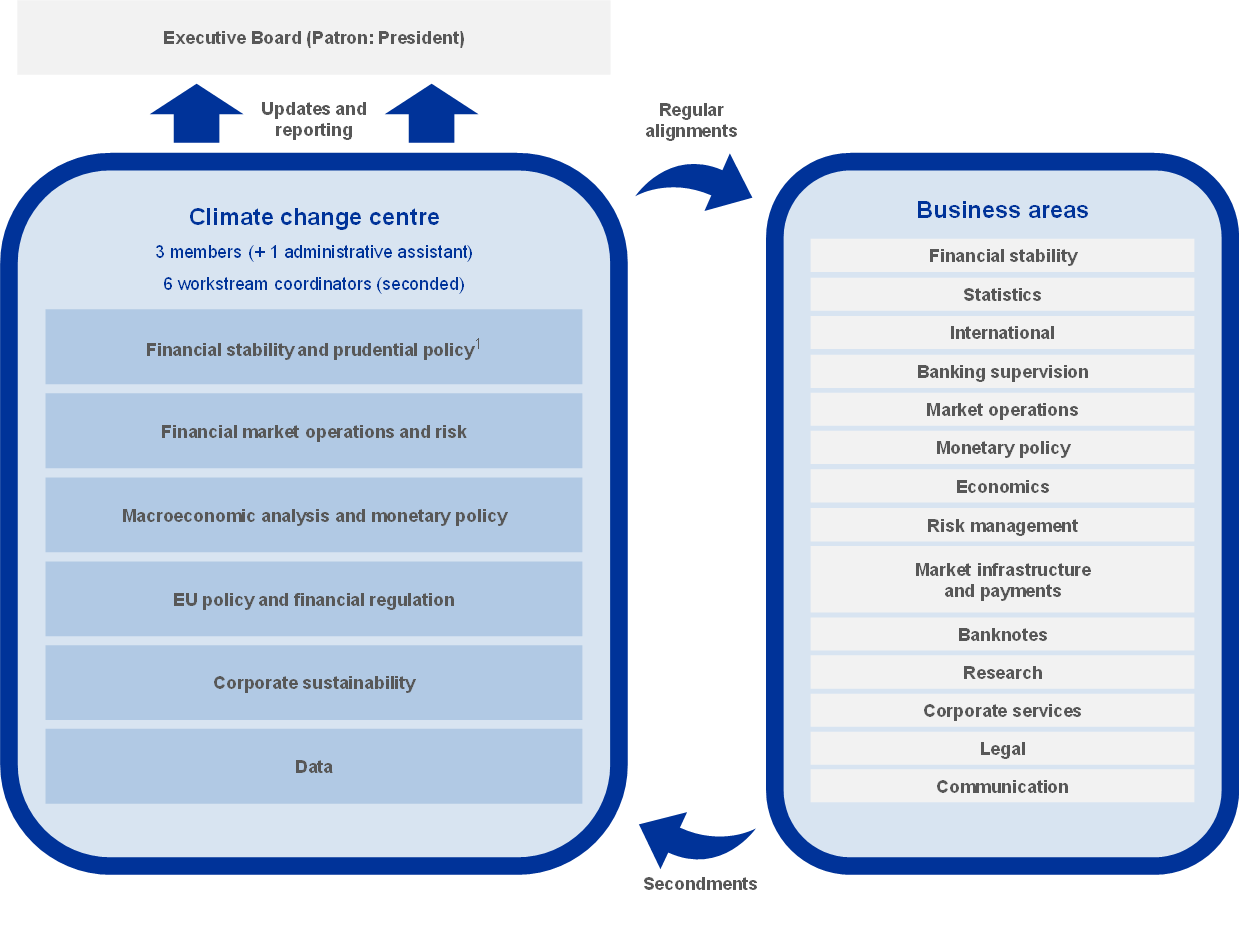

As part of the strategy review, the ECB also published an ambitious action plan on climate change, together with a detailed roadmap on how to incorporate climate change considerations into our monetary policy framework. That includes work on how to better capture the implications of a changing climate in our macroeconomic modelling, in addition to the development of new indicators for climate change risk analyses. The ECB’s climate change centre – launched in 2021 – will play an important role in coordinating related activities within the bank. And you can now learn all about the ECB’s sustainability-related activities and initiatives in a dedicated chapter of this Annual Report.

The ECB made some important changes to its communication too. In July, the Governing Council introduced its new-style monetary policy statement, which communicates its monetary policy decisions in a more accessible way. And the new statement is complemented with a visual version – “our monetary policy statement at a glance” – aimed at the wider public. It explains the ECB’s decisions using simple language and relatable visuals and is available in all official EU languages.

Support for the euro is strong, with 79% of euro area respondents to the Eurobarometer survey conducted in June-July 2021 in favour of the single currency. But the euro must be fit for the digital age. That is why in 2021 the Governing Council launched the 24-month investigation phase of a project for a possible digital euro. At the same time, cash will continue to play an important role in people’s lives. In December, the ECB announced plans to redesign future euro banknotes, with the design process drawing on input from citizens and the final designs expected to be selected in 2024.

So, changes are afoot for the euro in the years to come. But one thing will remain unwavering throughout: the ECB’s commitment to the single currency and price stability.

Frankfurt am Main, April 2022

Christine Lagarde

President

The year in figures

1 Strengthening economic outlook still clouded by pandemic development

In 2021 the global economy experienced a strong recovery, owing primarily to the reopening of economies amid rising rates of vaccination against COVID-19, and strong and timely policy support. However, the recovery was to some extent uneven across advanced and emerging market economies. Global inflation increased, reflecting mainly the sharp increase in energy prices and demand outpacing supply in some sectors in the face of headwinds from pandemic-related factors and other supply and transport bottlenecks. In the euro area, real GDP growth rebounded strongly in 2021, following the largest contraction on record in the previous year. This recovery, which brought with it improving labour markets, was supported by timely and determined monetary and fiscal policy measures. Economic uncertainty nonetheless remained elevated during the year and the difference between the two largest sectors, industry and services, was pronounced. Early in the year, growth was affected by lockdown measures and travel restrictions, which had a negative impact on the supply of and demand for services. Later, following the exceptionally strong rebound in global demand, the emergence of supply-side bottlenecks and higher energy costs curtailed production in the industrial sector. Euro area inflation as measured by the Harmonised Index of Consumer Prices (HICP) increased sharply to 2.6% in 2021, from 0.3% in 2020. It remained at subdued levels in the first few months, before picking up in the course of the year and reaching a rate of 5.0% in December. The upswing in prices reflected to a large extent a sharp and broad-based surge in energy prices, the demand and supply imbalances following the reopening of economies and more technical factors such as the reversal of the temporary VAT reduction in Germany. Beyond 2021, inflation was expected to remain elevated in the near term but to ease over the year 2022. However, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine significantly increased the uncertainty surrounding the inflation outlook.

1.1 Strong global recovery from the crisis with uneven progress

With rising vaccination rates and timely policy support, the global economy experienced a strong though uneven recovery

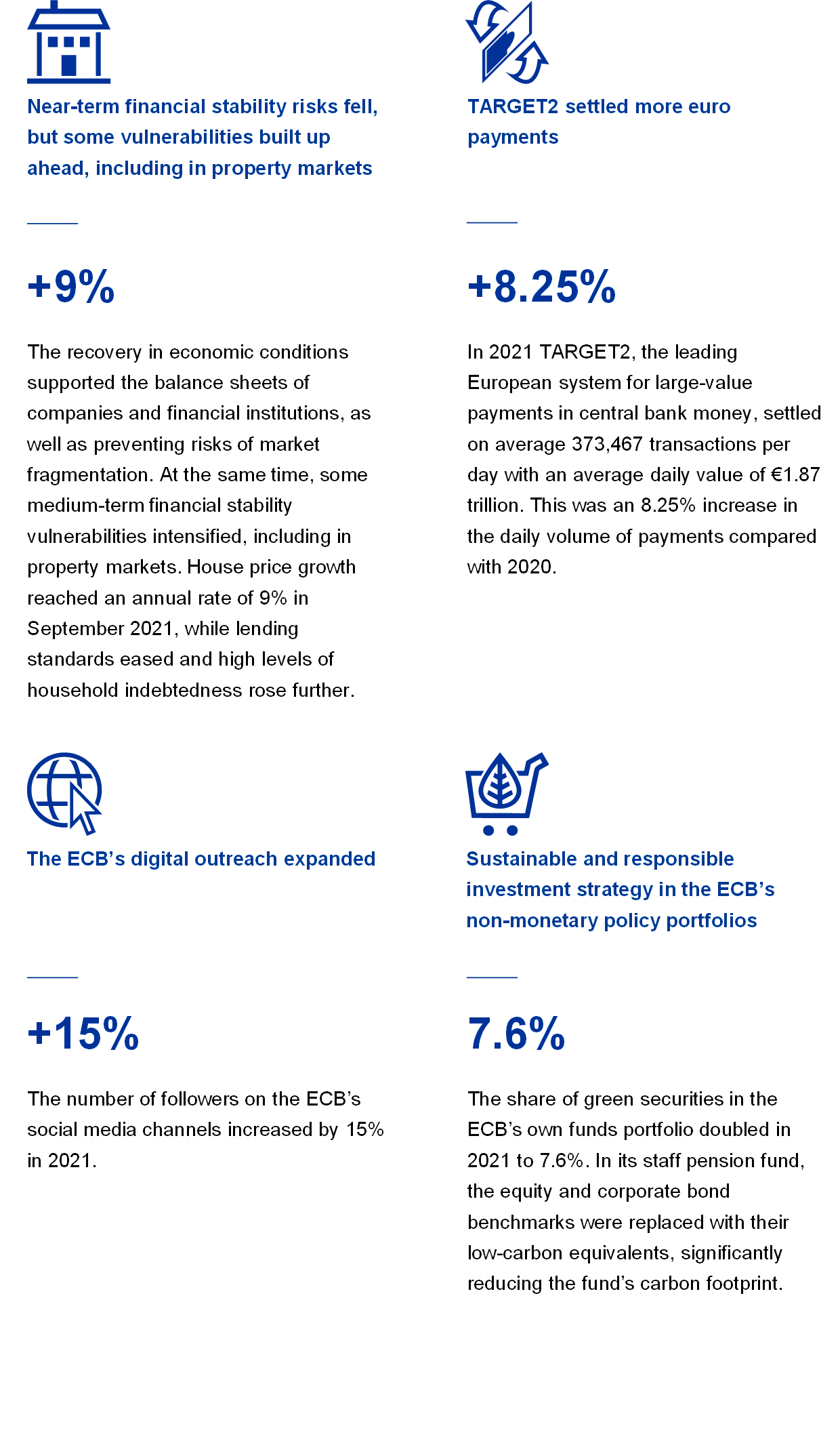

The global economy experienced a strong recovery from the crisis in 2021, but progress was uneven (see Chart 1.1). After contracting by 3.1% in 2020 in annual terms, global real GDP increased by 6.2% in 2021 despite new waves of the pandemic. The reopening of economies, rising rates of vaccination against COVID-19 and timely policy support were the main drivers of the rebound in economic activity, while global supply bottlenecks acted as headwinds to growth. While the recovery was global, it varied across countries. It was more pronounced in advanced economies, and more moderate in most emerging market economies, which had more limited vaccine supplies and less capacity to take supportive policy measures. In addition, the global economic growth momentum slowed towards the end of the year, mainly owing to a new wave of infections and renewed restrictions as well as persistent supply bottlenecks.

Chart 1.1

Global real GDP growth

(annual percentage changes, quarterly data)

Sources: Haver Analytics, national sources and ECB calculations.

Notes: The aggregates are computed using GDP adjusted with purchasing power parity weights. The solid lines indicate data and go up to the fourth quarter of 2021. The dashed lines indicate the long-term averages (between the first quarter of 1999 and the fourth quarter of 2021). The latest observations are for December 2021 as updated on 28 February 2022.

Global trade also recovered strongly, driven in particular by goods trade

Global trade also recovered strongly, but with weakening momentum in the second half of 2021 (see Chart 1.2). The strong rebound in global demand started above all in consumption, mainly of goods rather than services (e.g. travel and tourism), which faced more restrictions. In the second half of the year, trade in goods exceeded its pre-crisis level, although its expansion slowed amid persistent supply bottlenecks. The more contact-intensive services trade recovered more slowly, in line with the gradual pace of the easing of restrictions, and remained below its pre-pandemic level in 2021.

Chart 1.2

Global trade growth (import volumes)

(annual percentage changes, quarterly data)

Sources: Haver Analytics, national sources and ECB calculations.

Notes: Global trade growth is defined as growth in global imports including the euro area. The solid lines indicate data and go up to the fourth quarter of 2021. The dashed lines indicate the long-term averages (between the fourth quarter of 1999 and the fourth quarter of 2021). The latest observations are for December 2021 as updated on 28 February 2022.

Global inflation increased significantly as demand recovered amid supply bottlenecks and higher commodity prices

Global inflation increased significantly in 2021, in terms of both headline inflation and inflation measures such as those excluding food and energy (see Chart 1.3). In countries belonging to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), headline inflation increased to 6.6%, and inflation excluding energy and food increased to 4.6%. In most countries the increase mainly reflected higher energy and other commodity prices due to pandemic-related mismatches between constrained supply and strongly recovering demand. In the United States, where real GDP reached its pre-crisis level in the second quarter of 2021, inflation pressures intensified particularly strongly and broadened towards the year-end. Inflation pressures became also more broad-based in some emerging market economies.

Chart 1.3

OECD consumer price inflation rates

(annual percentage changes, monthly data)

Source: OECD.

Note: The latest observations are for December 2021 as updated on 28 February 2022.

Oil prices pushed up by recovering demand and supply-side constraints

Oil prices increased in 2021, from the pandemic low of around USD 10 per barrel to a high of USD 86 per barrel, leaving the price of the international benchmark Brent crude at USD 79 per barrel at year-end. With the economic recovery, oil demand rose towards pre-pandemic levels. In the second half of 2021, high gas prices also led to the substitution of gas with other energy sources, including oil. At the same time, oil supply lagged behind demand, partly due to capacity constraints in the US shale industry and the relatively moderate production increases implemented by the OPEC+ cartel.

The euro depreciated against the US dollar as monetary policy diverged between the euro area and the United States

The euro depreciated by 3.6% in nominal effective terms over the course of 2021. In bilateral terms, this was mainly driven by a depreciation of the euro against the US dollar by 7.7%, reflecting primarily the divergent developments in the monetary policy stance in the United States and in the euro area. The euro also depreciated against the pound sterling but strengthened against the Japanese yen.

The risks to global economic activity were tilted to the downside

At the end of 2021, the outlook for global growth remained clouded by the uncertain pandemic development amid uneven progress in global vaccinations. The emergence of the Omicron variant of the coronavirus, the resurgence of infections and the renewed tightening of containment measures all held risks to the pace of global economic recovery, as did the possibility of more persistent supply bottlenecks.

1.2 Swift rebound in the euro area economy[1]

Following a contraction by 6.4% in 2020, the largest on record, euro area real GDP grew by 5.3% in 2021 (see Chart 1.4). Growth dynamics during the year were still very much shaped by the evolving COVID-19 pandemic alongside elevated, but declining, economic uncertainty. In the first quarter, growth was still affected by lockdown measures and travel restrictions, which had a negative impact particularly on the consumption of services. The recovery began in the industrial sector, which recorded strong growth rates overall. As economies started to reopen and restrictions became looser in the second and third quarters, the services sector began to catch up, paving the way for a broader-based recovery. However, the exceptionally strong rebound in global demand during the second half of the year gave rise to supply-demand mismatches in various markets. These led to, among other things, a sharp increase in energy costs, which, together with some renewed intensification of the pandemic, dampened the strength of the recovery and increased inflationary pressures.

Chart 1.4

Euro area real GDP and demand contributions

(annual percentage changes; percentage point contributions)

Source: Eurostat.

Note: The latest observations are for 2021 (left-hand panel) and the fourth quarter of 2021 (right-hand panel).

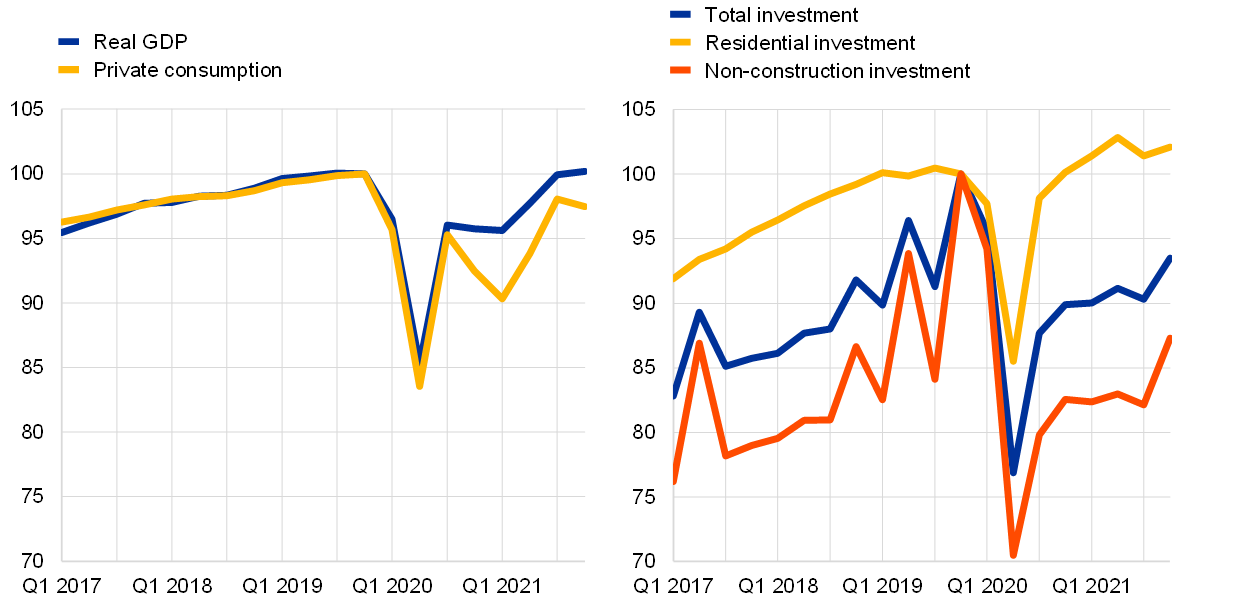

While these developments were common to all euro area countries, the extent to which countries have been able to recover from the pandemic has been somewhat uneven. This is largely due to the fact that the development of the pandemic has varied from country to country, but it also reflects differences in economic structure such as exposure to global supply chains and the importance of contact-intensive sectors such as tourism. By the end of 2021, output in the euro area was 0.2% above its level in the final quarter of 2019 (see Chart 1.5). However, underlying developments across countries were heterogeneous throughout the year, with, among the largest euro area economies, only France exceeding its pre-pandemic output level by the end of the year.

Chart 1.5

Euro area real GDP, private consumption and investment

(index: Q4 2019 = 100)

Sources: Eurostat and ECB calculations.

Notes: The latest observations are for the fourth quarter of 2021. In the final quarter of 2021, total investment and non-construction investment stood 6.5% and 12.7% below their pre-pandemic levels (fourth quarter of 2019). However, excluding data for Ireland, the respective end-2021 outcomes were 1.1% and 0.5% above the pre-pandemic levels. These substantial differences can be attributed to large multinational firms using Ireland as their base of operations, which leads to significant swings in investment in intellectual property products.

The recovery in euro area economic growth in 2021 was supported by timely and determined expansionary monetary and fiscal policies. Some measures also helped the economy adjust to structural changes triggered by the pandemic that are still under way. The ECB continued to provide substantial monetary policy support in 2021 to mitigate the impact of the pandemic. Accommodative monetary policy, including ample liquidity conditions, safeguarded the flow of credit to the real economy. As regards fiscal policies, euro area governments continued in 2021 to provide substantial budget support to mitigate the effects of the crisis through short-time work schemes, higher health-related spending, other forms of support to firms and households, and sizeable loan guarantee envelopes. At the EU level, implementation of the Next Generation EU programme began and the “Fit for 55” package was adopted to contribute to a stronger, greener and more even recovery across countries.

Private consumption was the key driver of the recovery in the euro area in 2021

Private consumption increased by 3.5% in 2021, rebounding particularly strongly in the second and third quarters, mainly on account of the easing in COVID-19 restrictions. Consumer confidence strengthened rapidly from spring onwards as vaccination rates increased and the fear of infection declined, while the financial situation of households improved, mainly reflecting positive labour income developments (see Chart 1.6). Government support for household disposable income was gradually withdrawn. The contribution of net fiscal transfers to real disposable income growth turned negative in the course of 2021 as the number of people in job retention schemes and other fiscal support declined. Driven by strong growth in wages and employment, labour income, which typically entails a higher propensity to consume than other sources of income, was the main contributor to real disposable income growth in 2021. Real disposable income growth was also supported by operating surplus, mixed and property income, whose contribution turned positive in the course of the year, while it was dampened by negative terms-of-trade developments. Following the pandemic-induced jump in 2020, the household saving ratio declined in 2021, although remaining above its pre-pandemic level given the containment measures still in place during the year and the lingering uncertainty. This meant that private consumption remained below its pre-pandemic level at the end of 2021 despite the strong recovery.

Chart 1.6

Euro area private consumption and the breakdown of household disposable income

(year-on-year percentage changes; percentage point contributions)

Source: Eurostat.

Note: The latest observations are for the third quarter of 2021 for disposable income and the contributions, and the fourth quarter of 2021 for private consumption.

The incipient recovery in business and housing investment was slowed by supply bottlenecks

Business investment (approximated by non-construction investment) gained momentum in the first half of 2021, as pandemic containment measures loosened and the economy reopened, in a context of continued favourable financing conditions. However, supply bottlenecks – visible in increasing supplier delivery times and input prices – weighed on the recovery from the middle of the year onwards, thus hampering business investment. Subsequently, soaring energy prices and the resurgence of the pandemic towards the end of the year exerted a further drag on business investment. At the end of 2021, business investment gained momentum again, but remained significantly below the level recorded in the last quarter of 2019 (see Chart 1.5). By contrast, housing (or residential) investment had already exceeded its pre-crisis level by the fourth quarter of 2020. In the following quarters, shortages of materials and workers took a toll on the profitability of construction activity. Nonetheless, favourable financing conditions and income support measures, as well as a large stock of accumulated savings, sustained housing demand. At the end of 2021, housing investment stood well above its pre-crisis level.

Euro area trade reached its pre-pandemic levels at the end of 2021, with net trade contributing positively to GDP growth for the year. On the import side, robust growth driven by the restocking cycle was curbed by strong price dynamics, especially on account of the surge in energy import prices. Exports, which had recorded a strong rebound driven by manufacturing at the end of 2020, were characterised by a two-speed recovery. While on the goods side momentum moderated from the second quarter onwards, as supply and transport bottlenecks hit crucial exporting industries, services exports benefited from the reopening of high-contact activities such as tourism. Both imports and exports stood above their pre-crisis level by the end of the fourth quarter of 2021.

Output growth continued to be uneven across sectors in 2021 (see Chart 1.7). Both industry and services contributed positively to growth; however, industry contributed the most to the rise in real gross value added.

Chart 1.7

Euro area real gross value added by economic activity

(left-hand panel: annual percentage changes, percentage point contributions; right-hand panel: index: Q4 2019 = 100)

Source: Eurostat.

Note: The latest observations are for 2021 (left-hand panel) and the fourth quarter of 2021 (right-hand panel).

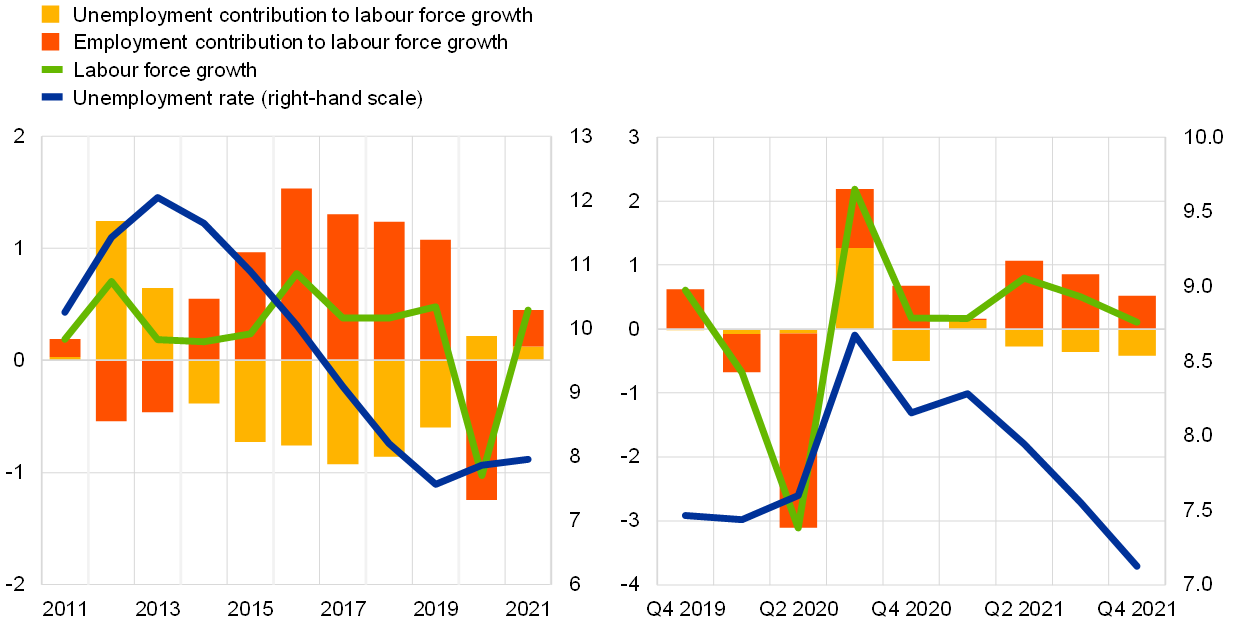

The labour market continued to recover but remained weaker than before the pandemic

The labour market showed a marked recovery alongside the rebound in euro area activity, although it remained weaker overall than before the pandemic. The unemployment rate declined gradually, from 8.2% in January 2021 to 7.0% in December, which was below pre-crisis levels (see Chart 1.8).[2] Also, while job retention schemes continued to play an important role in limiting job lay-offs, thereby helping to preserve human capital, the recourse to such schemes declined.[3] However, other labour market indicators remained weaker than their pre-pandemic levels. Hours worked for the fourth quarter of 2021 was 1.8% below its level in the final quarter of 2019, while the labour force participation rate for the third quarter of 2021 was around 0.2 percentage points lower (which represents a decrease of about 0.4 million workers) (see Chart 1.9). Weaker growth in the labour force was partly explained by muted net immigration in the euro area. The ongoing labour market adjustment varied across worker groups, partly reflecting the fact that some sectors were more heavily affected by containment measures and voluntary social distancing. In the third quarter of 2021 the labour force was around 4.2% smaller than before the pandemic for people with low skills and 1.7% smaller for those with medium skills, whereas it increased by about 6.8% for those with high skills.[4]

Chart 1.8

Unemployment and the labour force

(left-hand scale: quarterly percentage changes, percentage point contributions; right-hand scale: percentages of the labour force)

Sources: Eurostat and ECB calculations.

Note: The latest observations are for 2021 (left-hand panel) and the fourth quarter of 2021 (right-hand panel), which is based on implied monthly data.

Chart 1.9

Employment, hours worked and the labour force participation rate

(left-hand scale: index: Q4 2019 = 100; right-hand scale: percentages of working age population)

Sources: Eurostat and ECB calculations.

Note: The latest observations are for the fourth quarter of 2021 for employment and hours worked, and the third quarter of 2021 for the labour force participation rate.

While job vacancy rates picked up, employment growth was also robust

Elevated job vacancy rates, which were initially confined mainly to those sectors reopening after lockdown measures had been lifted, broadened out to other sectors as the recovery in activity progressed. Employment growth strengthened during the second and third quarters of 2021 and, despite some headwinds from supply bottlenecks in the manufacturing sector, remained robust and broad-based in the fourth quarter. This brought employment close to pre-pandemic levels in industry, construction and less contact-intensive services sectors. Employment levels in contact-intensive sectors remained relatively low compared with levels before the pandemic.

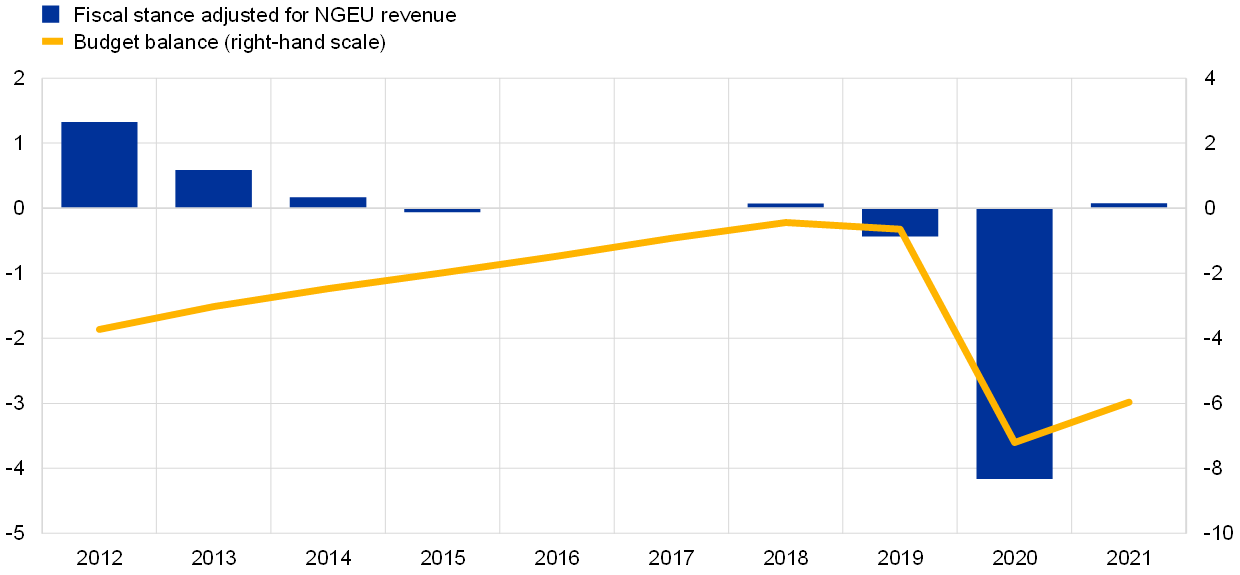

1.3 Fiscal policy measures in challenging times

Public finances were again dominated by the effects of the pandemic

In 2021 public finances in the euro area were dominated by the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic for the second year running. Particularly the first half of the year saw governments introducing additional large-scale support in response to renewed waves of the pandemic and the imperative of supporting the economic recovery. Still, according to the December 2021 Eurosystem staff macroeconomic projections, the general government deficit ratio for the euro area is projected to have decreased (see Chart 1.10) to 5.9% of GDP in 2021 from 7.2% in 2020 thanks to a strong improvement in economic activity. The continuation of high levels of fiscal support in 2021 was reflected in the fiscal stance adjusted for Next Generation EU (NGEU) grants[5], which was broadly neutral in 2021 following very expansionary policy in 2020.

Chart 1.10

Euro area general government balance and fiscal stance

(percentages of GDP)

Sources: Eurosystem staff macroeconomic projections for the euro area, December 2021 and ECB calculations.

Note: The measure of the fiscal stance takes into account expenditures funded by the NGEU Recovery and Resilience Facility and other EU structural funds (see footnote).

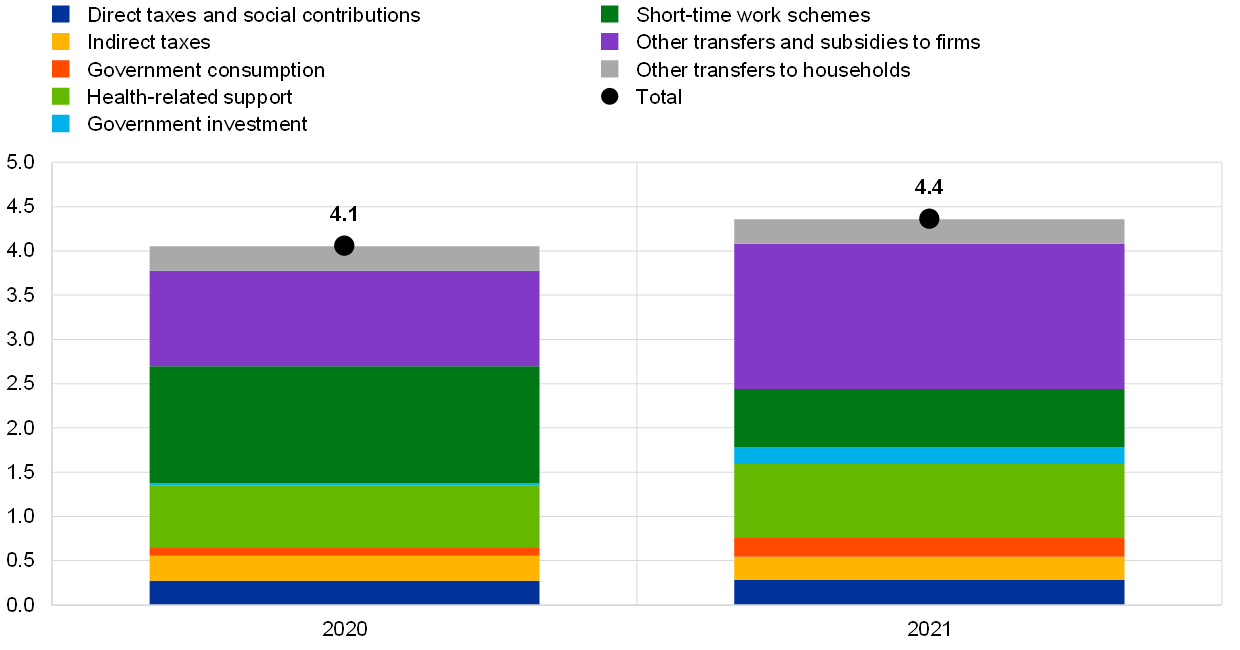

Crisis and stimulus measures increased somewhat, as transfers to companies rose but short-time work schemes were scaled back

As a share of GDP, crisis-related and recovery stimulus measures in the euro area increased to 4.4% in 2021 from 4.1% in the preceding year (see Chart 1.11). This increase was due to a significantly larger amount of government transfers to companies but also due to intensified health-related support as well as government investment. These increases were, however, largely offset by the declining use made of short-time work schemes. While such schemes were the most important instrument of government support in 2020, these were gradually reduced in 2021, as restrictive measures were eased and labour markets started to recover in line with a broad upswing in economic activity. The improvement in output also explains why the debt-to-GDP ratio of the euro area fell marginally to 97% in 2021, following a large increase in the previous year.

Chart 1.11

Crisis-related and recovery stimulus measures in the euro area

(percentages of GDP)

Sources: Eurosystem staff macroeconomic projections for the euro area, December 2021 and ECB calculations.

Note: The health-related support is netted out of the other components shown, with most of the impact for government consumption.

Next Generation EU is a cornerstone of Europe’s response to the economic challenges of the pandemic

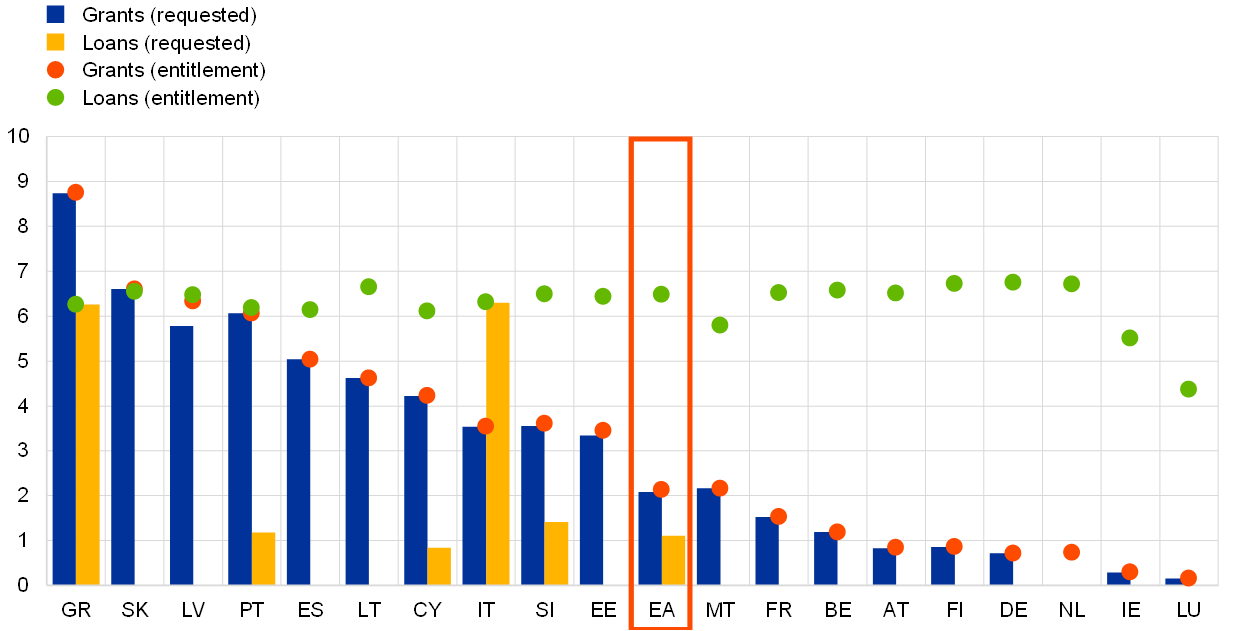

Governments’ responses to the fiscal needs over the last two years have been in the first place through national policies, but increasingly also through EU-wide initiatives. A cornerstone of Europe’s common policy response was put in place in July 2020 when the EU announced Next Generation EU (NGEU), an EU-wide investment and reform programme. NGEU offers financial support to EU Member States, conditional on the implementation of concrete investment and reform projects over the period 2021-26. To this end, it mobilises a funding volume of up to €807 billion in current prices, out of which €401 billion (3.5% of euro area GDP) is targeted at euro area countries and the remaining part at other EU Member States. About half the funds from the Recovery and Resilience Facility, by far the largest NGEU programme, are made available in the form of loans and half in the form of non-repayable grants. In practice, however, the grant component is expected to be predominant, as all euro area countries intend to make full use of their grants, while only a few have requested loans so far. A noteworthy feature of transfers from the Recovery and Resilience Facility is that countries that have been hit hardest by the pandemic or have relatively low GDP per capita are eligible for a larger share (see Chart 1.12 for entitlements per country). Particularly if recovery and resilience plans are well implemented, this feature should contribute to alleviating cross-country divergences in economic growth that the pandemic has further exacerbated in the euro area.

Chart 1.12

Recovery and Resilience Facility entitlements and funding requested for euro area countries by end-2021

(percentages of 2020 GDP)

Sources: European Commission and ECB calculations.

Notes: EA: euro area. Grant entitlements for countries are shown according to European Commission data. Loan entitlements for countries are calculated as 6.8% of their 2019 gross national income. No information is available on Recovery and Resilience Facility grant and loan requests for the Netherlands as this country has not yet submitted its recovery and resilience plan.

1.4 Upswing in inflation driven by heterogeneous effects

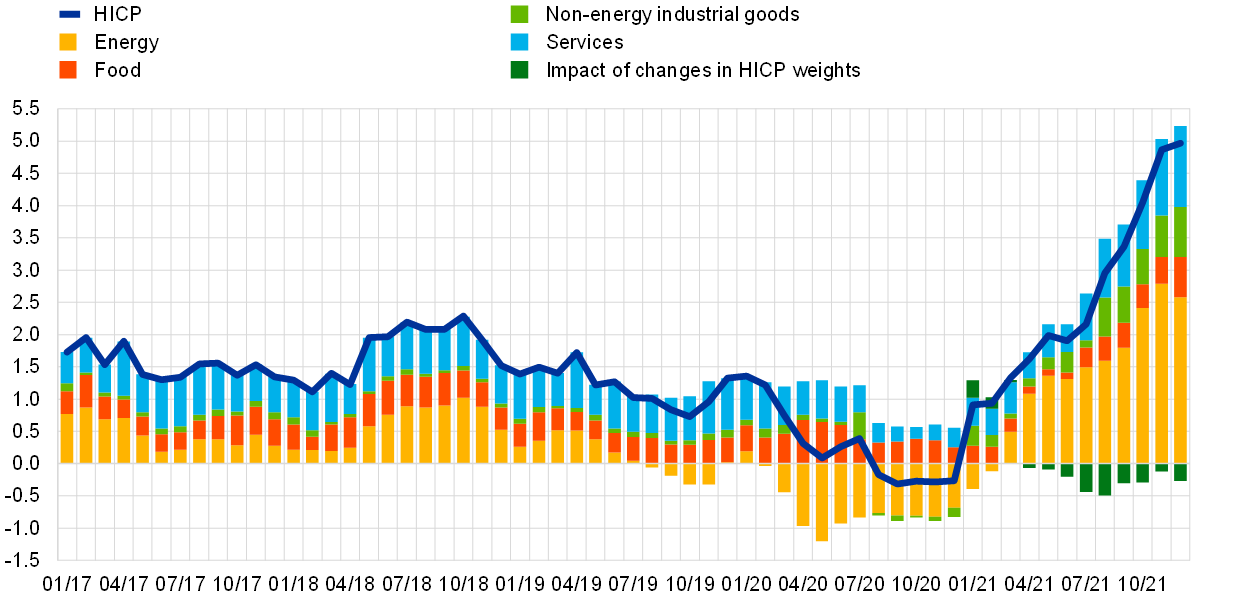

Headline HICP inflation in the euro area was 2.6% on average in 2021, sharply up from an average of 0.3% in 2020 (see Chart 1.13). This upswing reflected to a large extent the marked increase in energy prices. In addition, demand outpacing constrained supply in some sectors added to inflationary pressures, following the easing of pandemic restrictions and the strong rebound of the global and domestic economies. The surge from -0.3% annual inflation in December 2020 to 5.0% in December 2021 was unprecedented in terms of both steepness and the magnitude of the annual growth rates at the end of 2021 (Box 1 provides more details on the factors behind this rise). Moreover, it came with repeated upward surprises in the actual inflation numbers. Looking ahead, the factors behind the increase in inflation in 2021 were largely expected to fade and, after remaining elevated in the near term, inflation was expected to ease in the course of 2022. Following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, however, uncertainty surrounding the inflation outlook increased significantly.

Energy inflation, the reopening of services and supply bottlenecks were behind the surge in inflation

The main contributor to the pick-up in headline inflation in 2021 was the energy component. However, from the summer onwards, the contributions of other components also became more pronounced. Easing of pandemic lockdowns and other restrictions and expansionary fiscal and monetary policies allowed demand to recover, providing a boost especially to consumer services. At the same time, strong global demand and supply bottlenecks, as well as energy prices, pushed up the cost of imported and domestically produced goods. This was also reflected in higher contributions to inflation from the non-energy industrial goods (NEIG) and services price components later in the year (see Chart 1.13). Inflation was also sustained to some extent in the second half of the year by the effect of the previous year’s temporary VAT reduction in Germany.

Chart 1.13

Headline inflation and its components

(annual percentage changes; percentage point contributions)

Sources: Eurostat and ECB calculations

Notes: Contributions of HICP components for 2021 are computed using HICP weights for 2020. The impact of the changes in weights is estimated by the ECB. The latest observations are for December 2021.

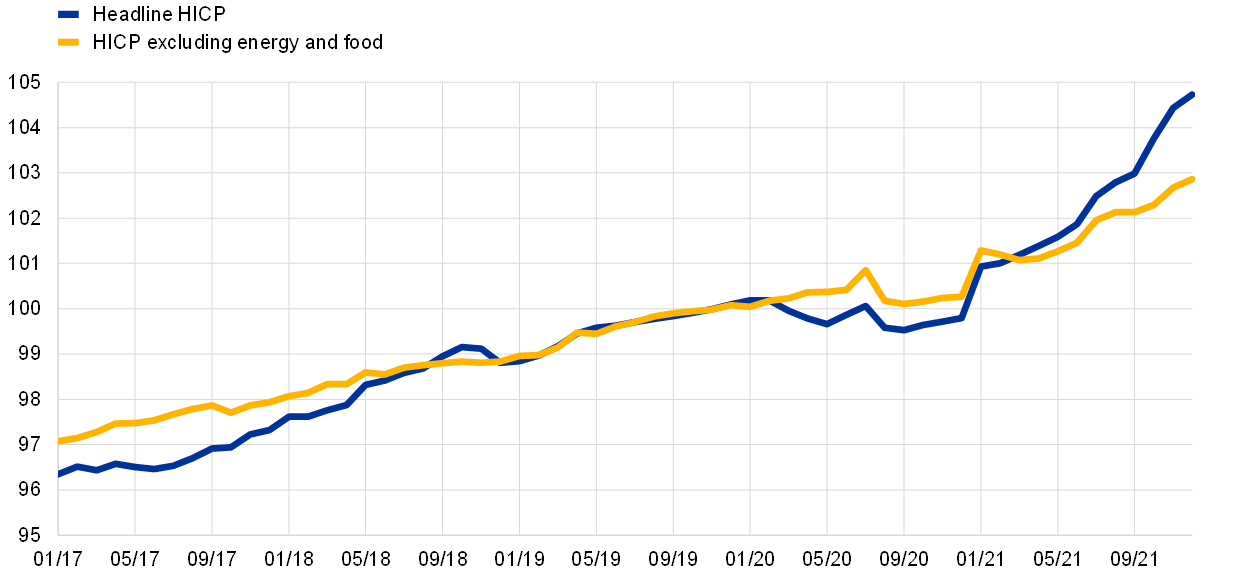

The price level also increased dynamically in the course of 2021

As the annual rates of change also reflect the low starting point of the previous year, price dynamics in 2021 can also be considered in terms of the development of the indices for headline HICP and HICP excluding energy and food. The rise in the price level in the course of 2021 was steeper than seen over the years prior to the pandemic, when inflation outcomes were below the ECB’s inflation aim (see Chart 1.14).

Chart 1.14

Headline HICP and HICP excluding energy and food

(seasonally and working day-adjusted indices, Q4 2019 = 100)

Sources: Eurostat and ECB calculations.

Notes: The latest observations are for December 2021.

Measurement-related factors distorted inflation numbers in 2021

Gauging price dynamics and the factors driving them was particularly challenging in 2021, not just because of the economic impact of the pandemic but also because of certain pandemic-related technical factors that affected the measurement of inflation. The first of these factors was the regular annual adjustment of the consumption weights for the compilation of the HICP.[6] Usually, these adjustments are small, but in 2020 consumption patterns changed markedly in response to the pandemic and the various restrictions in place. For example, travel-related HICP items received a smaller weight in the 2021 HICP basket on account of the subdued tourism seasons in 2020. Overall, changes in weights had sizeable impacts, more often downward than upward, on the annual inflation rates in individual months of 2021. For the year 2021 as a whole the total estimated impact was a negative effect of 0.2 percentage points (see Chart 1.13). A second technical factor was that in several months of 2020 and 2021 prices for several HICP items (for example restaurants and travel) could not be collected via usual sources owing to COVID-19 restrictions and were replaced with prices which were imputed, i.e. obtained by other methods.[7] A third technical factor was the fact that seasonal sale periods were moved out of their usual months in 2020 and 2021, which implied substantial volatility for the annual rate of change in non-energy industrial goods prices owing to the clothing and footwear components.

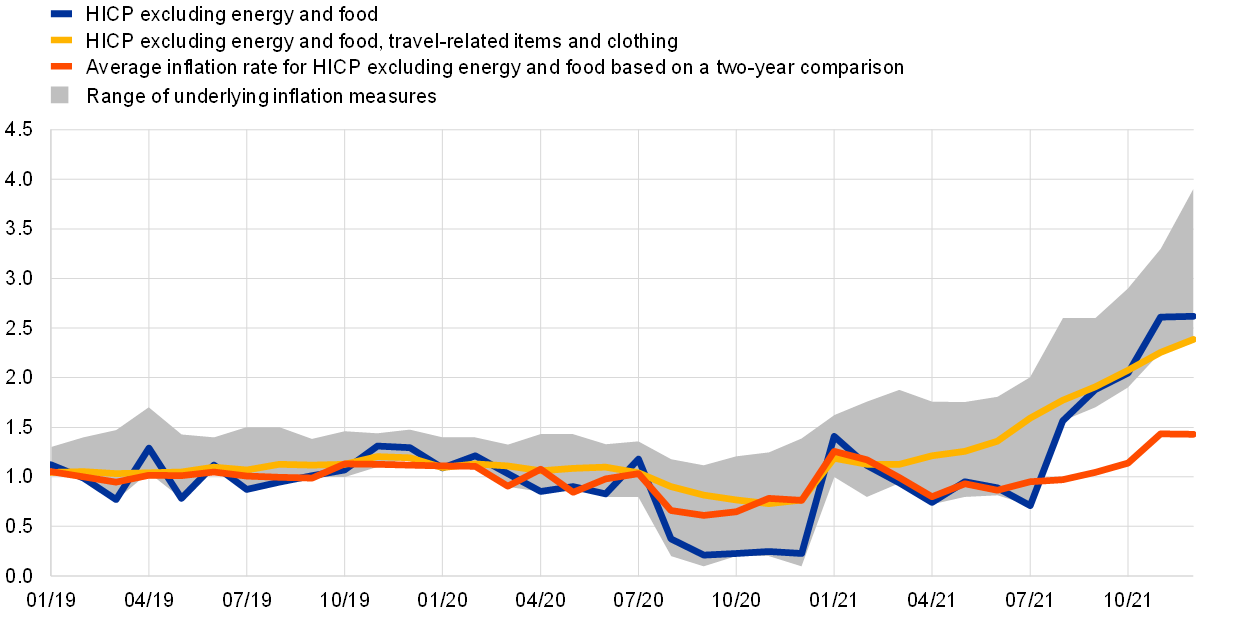

Underlying inflation rose, but more moderately when the pandemic-related volatility is filtered out

Given these technical factors, some caution is also warranted when interpreting developments in HICP inflation excluding energy and food. Various indicators of underlying inflation, including exclusion-based measures, statistical measures and econometrically estimated measures, also picked up throughout the year (see Chart 1.15).[8] At the end of the year inflation rates on the basis of these measures were between 2.4% and 3.9%. In addition, price dynamics in 2020 were generally subdued and therefore imply upward base effects for rates of change in 2021. Considering this aspect, an alternative way to look at inflation developments in 2021 is to refer to the rates of change in prices over the same month two years earlier, divided by two to reflect the average change per year. Looking at this rate effectively minimises distortions stemming from the very low inflation at the beginning of the pandemic period. Calculated on this basis, HICP inflation excluding energy and food was 1.4% in December 2021 and thus roughly half the published annual growth rate of 2.6% (see Chart 1.15). However, this series also increases over the last months of 2021, to a rate last recorded for 2013, in the early years of the low inflation decade before COVID-19.

Chart 1.15

Indicators of underlying inflation

(annual percentage changes)

Sources: Eurostat and ECB calculations.

Notes: The range includes permanent and temporary exclusion-based measures, statistical measures and econometric measures (Supercore and the Persistent and Common Component of Inflation (PCCI)), see footnote 8 for a description of underlying inflation measures. The latest observations are for December 2021.

Producer prices for goods rose strongly while labour costs remained moderate

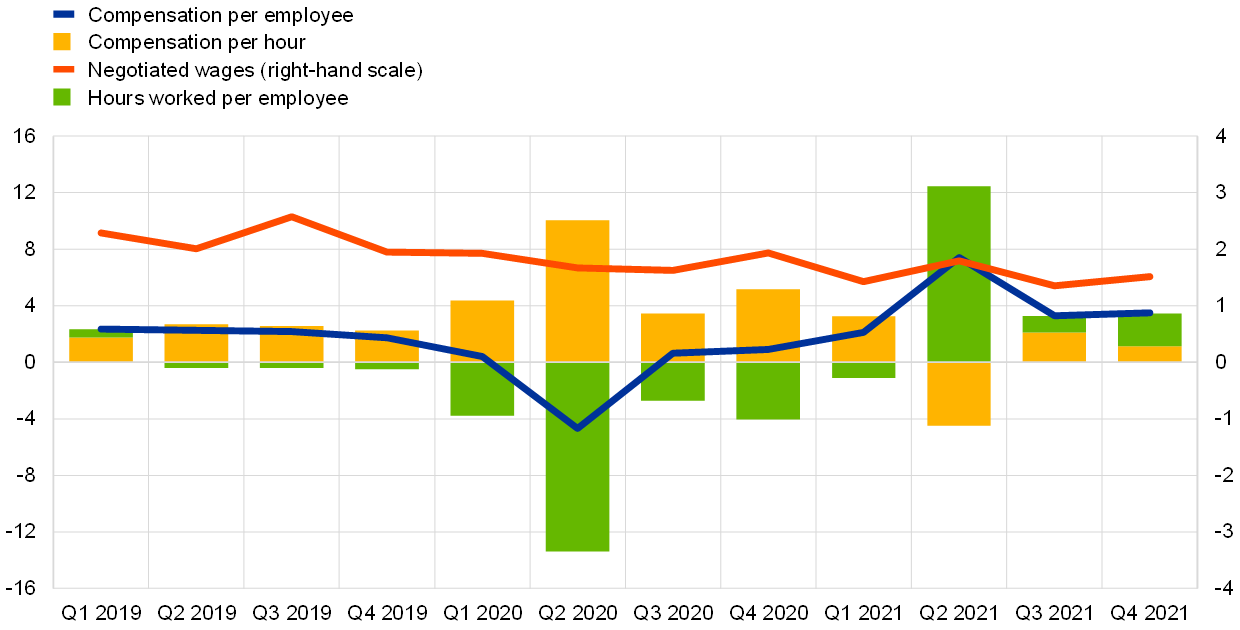

Cost pressures played an important role in shaping developments in consumer price inflation in 2021. Pipeline pressures at all stages of the pricing chain increased significantly, most prominently at the early stages and in prices of intermediate goods, which reflected the effect of supply bottlenecks and, especially in the second half of 2021, to some extent also the increase in energy prices. Price increases for imported products were somewhat higher than in 2020, in part because of a depreciation of the euro. The impact of cost pressures on producer prices for non-food consumer goods – an important indicator for the dynamics of non-energy industrial goods prices – was more moderate than at the earlier stages of the pricing chain, albeit still at a historical high. A broad measure of domestic cost pressures is the growth in the GDP deflator, which was on average 2.0% in 2021, and thus above the average of the previous year. Strong base effects and the impact of government support measures led to some volatility in the cost components related to unit labour costs and unit profits. As the reliance on job retention schemes declined and most employees went back to full salaries, the growth in compensation per employee increased to an average 4.0% in 2021, from -0.6% in 2020. As at the same time productivity per person increased given the additional hours worked, this stark increase was not mirrored in unit labour costs. The impact of government support schemes thus continued to make wage indicators such as compensation per employee and compensation per hour worked (see Chart 1.16) more difficult to interpret. Growth in negotiated wages is less affected by such measures and remained moderate, falling to 1.5% on average in 2021 from 1.8% in 2020.[9] However, this possibly also reflected pandemic-related delays in wage bargaining rounds.

Chart 1.16

Labour cost measures

(annual percentage changes)

Sources: Eurostat, ECB and ECB calculations.

Notes: The latest observations are for the fourth quarter of 2021 for negotiated wages and the third quarter of 2021 for the rest.

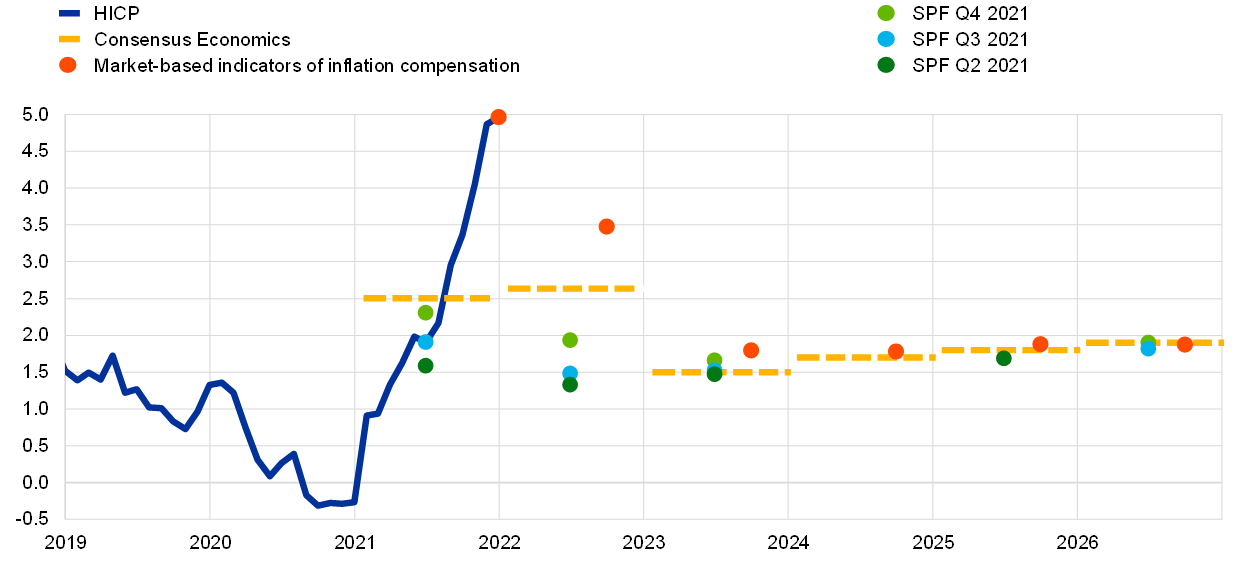

Measures of longer-term inflation expectations rose towards the ECB’s inflation target

Longer-term inflation expectations of professional forecasters, which had stood at 1.7% at the end of 2020, rose to 1.9% over the course of 2021 (see Chart 1.17). According to the results of a special questionnaire sent to respondents to the ECB’s Survey of Professional Forecasters (SPF), the communication of the new monetary policy strategy helped to support this adjustment in expectations.[10] Market-based measures of longer-term inflation compensation, in particular the five-year inflation-linked swap rate five years ahead, followed a similar path and gradually picked up in the course of 2021. Towards the end of the year, this measure hovered just below the level of 2%, briefly surpassing it in October. Estimates of inflation risk premia included in inflation compensation demanded by investors suggest that inflation risk premia turned positive across maturities in 2021 for the first time in several years. Adjusting inflation compensation for this shows that the upturn in genuine longer-term inflation expectations embedded in market-based measures of inflation compensation was more subdued.[11]

Chart 1.17

Survey-based indicators of inflation expectations and market-based measures of inflation compensation

(annual percentage changes)

Sources: Eurostat, Refinitiv, Consensus Economics, ECB (SPF) and ECB calculations.

Notes: The path of market-based indicators of inflation compensation is based on the one-year spot inflation-linked swap (ILS) rate and the one-year forward ILS rates one, two, three and four years ahead. The latest observations for ILS rates are for 30 December 2021. The SPF for the fourth quarter of 2021 was conducted between 1 and 11 October 2021. The Consensus Economics cut-off dates are 8 December 2021 for forecasts for 2021 and 2022, and 14 October 2021 for the longer-term forecasts.

Prices for homeowners increased whereas rent dynamics remained moderate

The review of the monetary policy strategy identified a need to include owner-occupied housing costs in the HICP. Significant progress on developing related indicators was achieved in 2021. However, more needs to be done, for example by better isolating the consumption component from the investment component of the property purchases included in the estimates.[12] An experimental index that combines the HICP basket with the expenditure on owner-occupied housing could already be made available by the European Statistical System in 2023, to be followed by an official index in approximately 2026. As yet, only experimental estimates are available for these costs, which are likely to have increased at an average annual rate of 4.8% in the first three quarters of 2021, up from 2.6% in 2020, and thus were considerably more dynamic than rents, which are included in the HICP. HICP rents of tenants rose by 1.2% in 2021, compared with 1.3% in 2020. The higher increase in housing costs for homeowners partly reflects the nature of the estimate: the index includes a component related to purchases of new dwellings, which has a close alignment with house prices. Looking at house prices, the growth in the ECB’s residential property price indicator increased to an average of 7.5% year on year in the first three quarters of 2021, from 5.4% in 2020. The buoyant housing market was reflected in HICP dynamics in some smaller items. For instance, until the pandemic restrictions eased significantly in late spring 2021, people spent more time at home. This change led to a rise in demand for home renovation, with a related upward dynamic in prices for goods and services related to housing, such as maintenance and repair and the laying of carpets and flooring.

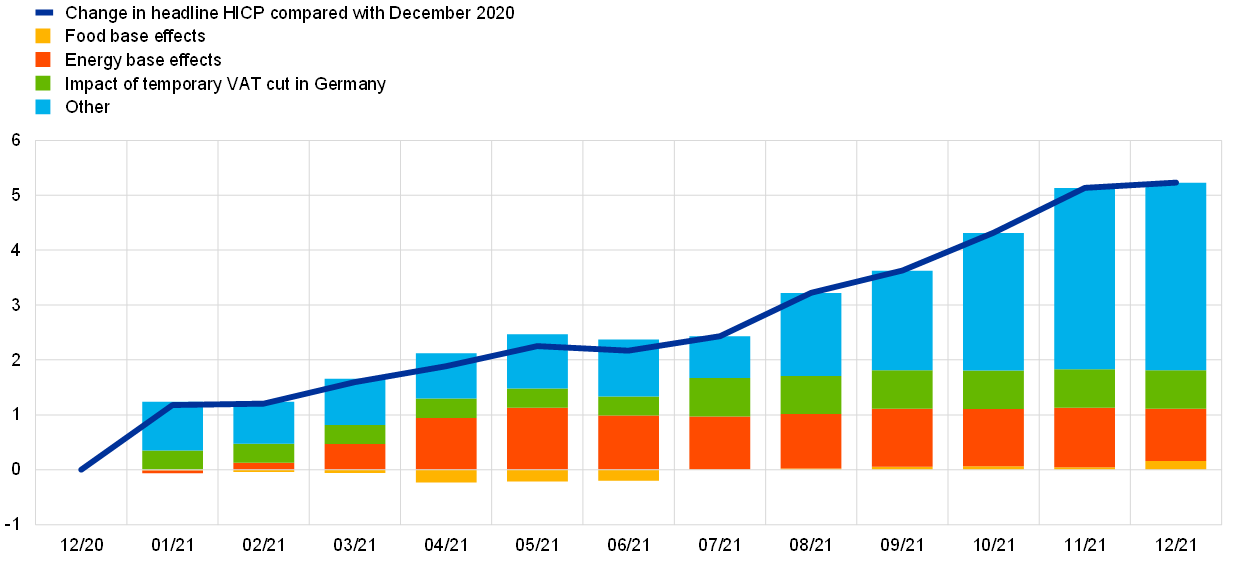

Box 1

Factors underlying the surge in HICP inflation

The euro area annual headline HICP inflation rate reached 5.0% in December 2021, compared with -0.3% in December 2020, 0.3% for 2020 as a whole and 0.9% on average over the five years before the pandemic. This increase mainly reflected a strong rise in energy inflation, but also a strengthening of HICP inflation excluding energy and food as demand outpaced constrained supply in some sectors amid the global and euro area recovery from the pandemic. Firms may have also raised prices to compensate for the revenue losses incurred during more stringent COVID-19 restrictions.

The low price levels in 2020 are an important factor when assessing the inflation surge in the course of 2021, as these provide the base for the calculation of annual growth rates for 2021. For instance, oil prices, and subsequently consumer energy prices, collapsed with the onset of the pandemic. Around half the energy inflation in the last quarter of 2021 can be attributed to the low 2020 level.[13] For food prices this effect worked in the opposite direction, as following the pandemic-related spike in spring 2020 developments in food prices were relatively moderate in the first half of 2021. Base effects also stemmed from changes in indirect taxes, especially the temporary cut in the VAT rate implemented in Germany from July to December 2020 in response to the crisis. The reversal of the cut lifted the euro area inflation rate in January 2021, but it also had an upward impact in the second half of 2021 because the comparison with the level a year previously was based on prices reflecting the reduced tax rate.[14] While within-year price dynamics played a larger role, the effects on annual inflation rates related to the low base in 2020, when combined, explain nearly 2 percentage points of the total 5.3 percentage point increase in the headline HICP inflation rate in December 2021 in comparison with December 2020 (see Chart A).

Chart A

Cumulative change in the headline HICP inflation rate during 2021 compared with December 2020

(percentage points)

Sources: Eurostat and ECB calculations.

Notes: The chart shows, for each month of 2021, the difference between the inflation rate in that month and the inflation rate in December 2020. For example, in August 2021 the inflation rate was around 3 percentage points higher than in December 2020 and around half of this difference can be explained by a base effect, i.e. the low level of the base for comparison in 2020.

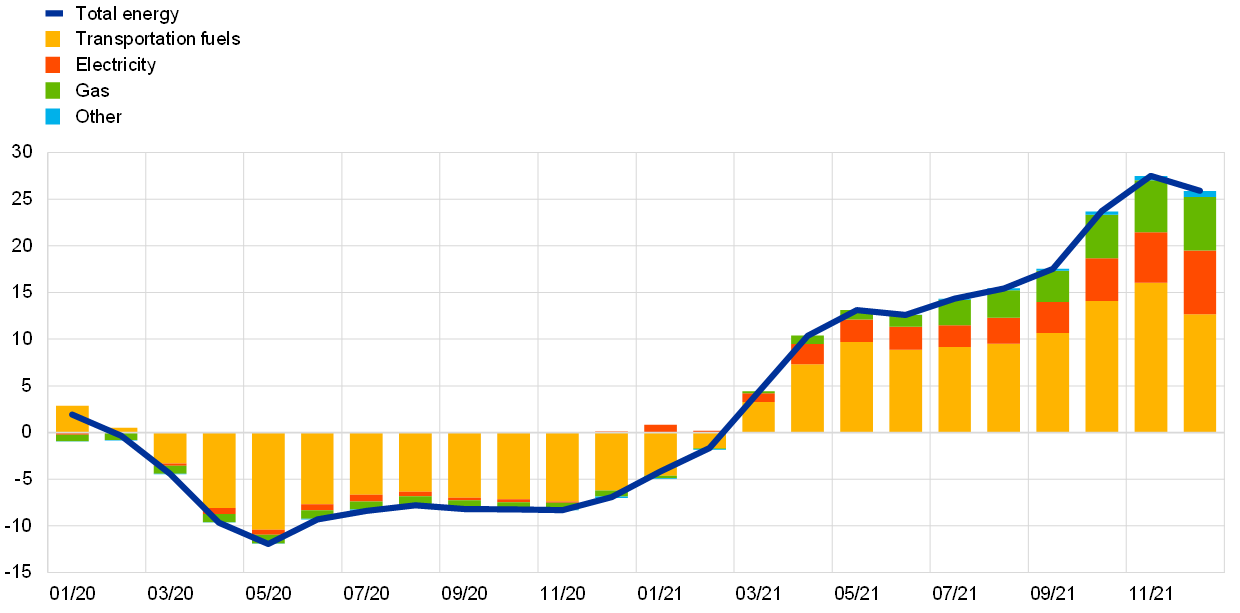

A second factor in the inflation surge was the fact that consumer energy prices did not just normalise in 2021 but kept increasing strongly. The additional rise was initially seen mainly in prices for transportation fuels, as global demand for oil strengthened in line with the ongoing recovery while supply remained somewhat restrained. Later in the summer, gas and electricity prices also surged (see Chart B, panel a). This reflected higher demand but also some supply constraints for gas. Demand for gas in Europe was extraordinarily high due to a cold winter 2020/21 and calm winds during the summer of 2021, which led to the substitution of wind-generated energy with gas.[15] Moreover, gas supply from Norway was reduced in the first half of the year owing to maintenance work on pipelines, and in the summer EU imports of gas from Russia were relatively low. The global recovery also raised demand for gas, especially in China. Consumers spend a larger share of their energy expenditure on transportation fuels (around 40%) than on gas (around 30%) and electricity (around 20%), and the developments in prices for fuels are usually the main determinant of energy inflation. However, the rise in gas and electricity prices in autumn 2021 resulted in a historically high contribution of these items to energy inflation in the euro area (see Chart B, panel b).

Chart B

Developments in energy inflation

(annual percentage changes; percentage point contributions)

a) Annual HICP inflation rate for energy and its main components

b) Contribution of the main components to the annual inflation rate for energy

Sources: Eurostat and ECB calculations.

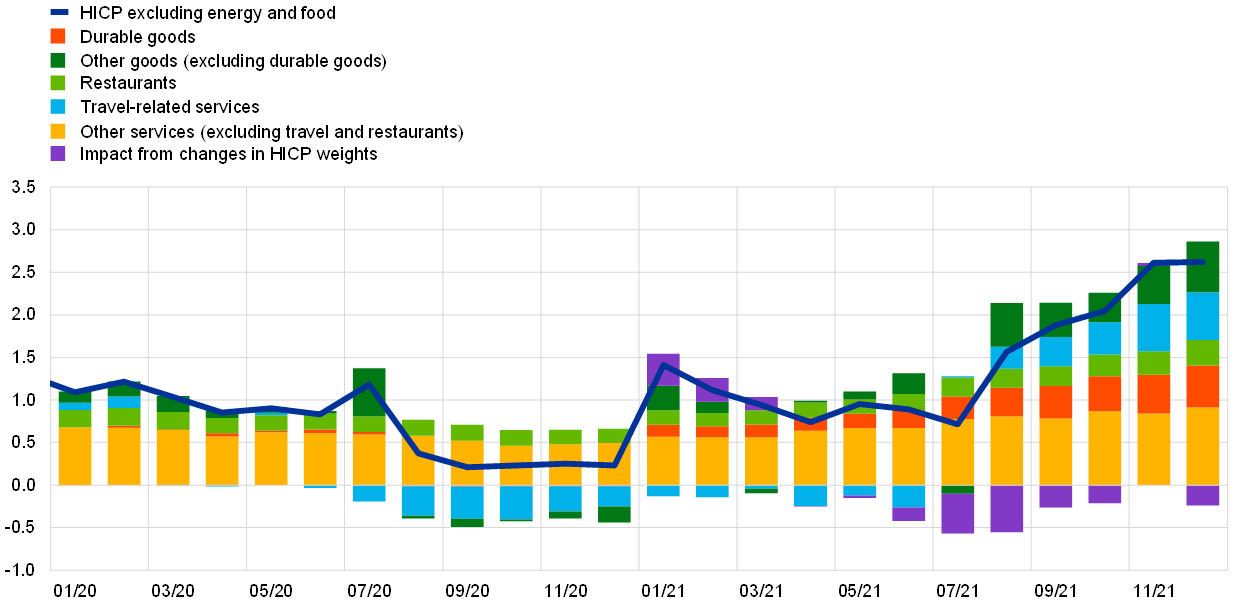

The third main factor in the surge in inflation was the price pressures emerging in the context of the reopening of the economy after a period of pandemic-related restrictions. Demand picked up strongly, both globally and domestically, outpacing constrained supply in some sectors. As a result, supply shortages emerged at the global level and transportation costs rose sharply around the turn of 2020/21.[16] Euro area producer prices rose steadily throughout 2021, not only for intermediate goods but also for consumer goods. There is no immediate and stable link between producer and consumer prices, but the gradual rise in consumer prices for durable goods particularly in the second half of 2021 was noticeable (see Chart C).[17] Price dynamics became more pronounced for new and used cars, bicycles and motorcycles, as well as various electronic items such as IT products and televisions, all items that are likely to have been affected by production shortages such as those related to semiconductors or by bottlenecks in global shipping and delivery chains.

Chart C

Decomposition of HICP inflation excluding energy and food

(annual percentage changes; percentage point contributions)

Sources: Eurostat and ECB calculations.

Notes: Contributions from the components for 2021 are calculated using 2020 HICP weights. The impact of changes in HICP weights is estimated by the ECB.

One of the sectors most heavily affected by the pandemic restrictions was “high-contact” services. Once the restrictions gradually eased, the price dynamics for these items started to strengthen. For instance, the increase in the annual rate of change for travel-related services (such as accommodation, transportation by air and package holidays) was particularly visible at the start of the holiday season in summer 2021 (see Chart C).[18] This increase, like that in energy prices, also partly reflected the comparison with the low prices in the previous year. In addition, price dynamics for restaurant prices also gradually strengthened after the reopening in spring 2021. The higher inflation rates for high-contact services reflected not only the sudden re-emergence of demand but also the higher costs and reduced capacity resulting from pandemic-related requirements as well as labour shortages as some firms found it difficult to rehire staff laid off during closures.

Finally, inflation volatility in 2021 was affected by a number of other specific factors as described in the main text of Section 1.4. For example, price dynamics for clothing and footwear were affected by changes in the timing of seasonal sales, and the change in weights for HICP items was unusually large for 2021, with a particularly sizeable effect in HICP inflation excluding energy and food (see Chart C).

Overall, the rise in HICP inflation in 2021 was related mainly to special factors emerging in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic and economic recovery. The unprecedented nature of the crisis and the specificity of the factors behind the surge in inflation during the recovery imply particularly high uncertainty and challenges in assessing inflation developments in the period ahead.

1.5 Continued decisive policy measures kept credit and financing conditions supportive

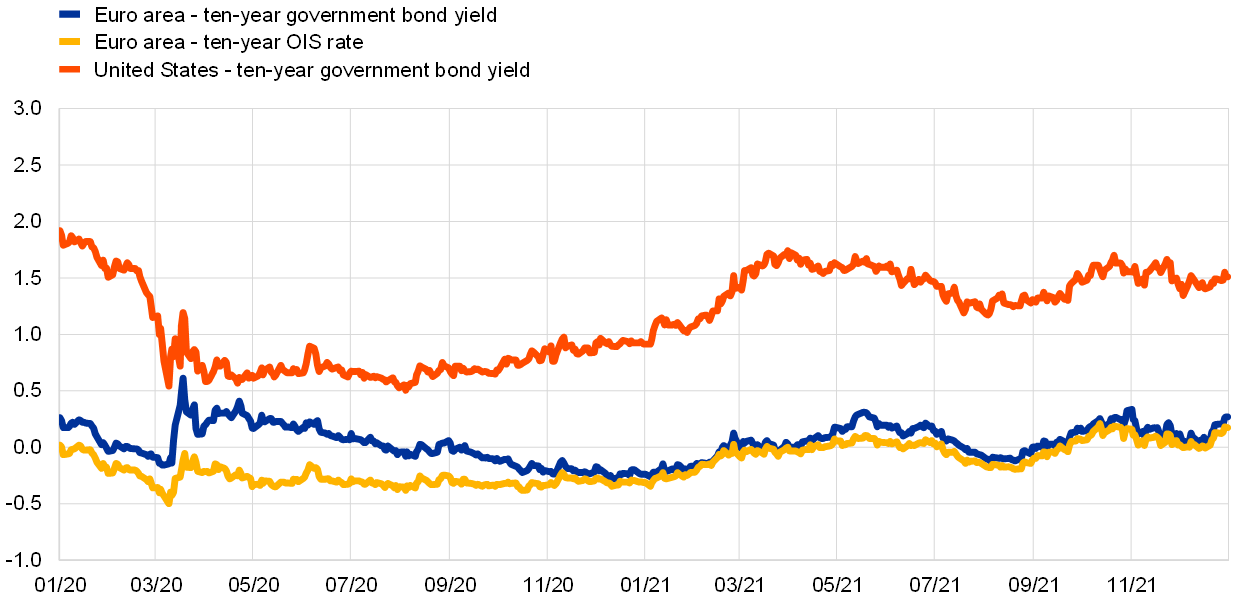

Continued asset purchases and ECB communication dampened upward pressures on long-term yields

Together with improvements in the fight against the pandemic, stimulus from fiscal, monetary and prudential policy lent support to the vigorous rebound of economic activity in 2021 (see Section 1.2). In the second half of the year investors also began to demand higher compensation for exposure to inflation dynamics, revising up their long-term inflation expectations and risk premia, which led to a rise in long-term interest rates (see Chart 1.18). Against this background, the ECB reconfirmed its accommodative policy stance and its commitment to maintaining favourable financing conditions in the euro area. This helped, at least partially, to shield euro area yields from global market developments in which higher than expected inflation led market participants to price in an earlier than previously expected tightening of monetary policy in a number of advanced economies. Furthermore, the ECB’s communication on its supportive monetary policy stance and continued large-scale asset purchases helped to prevent sovereign bond yield spreads from rising, i.e. the development in sovereign yields remained close to that of corresponding risk-free rates. As a result, the euro area GDP-weighted average of ten-year government bond yields increased steadily in 2021 and stood at 0.27% on 31 December, 51 basis points higher than its level at the end of 2020 (see Chart 1.18). More generally, financing conditions in the euro area remained supportive.

Chart 1.18

Long-term yields in the euro area and the United States

(percentages per annum, daily data)

Sources: Bloomberg, Refinitiv and ECB calculations.

Notes: The euro area data refer to the GDP-weighted average of ten-year government bond yields and to the ten-year overnight index swap (OIS) rate. The latest observations are for 31 December 2021.

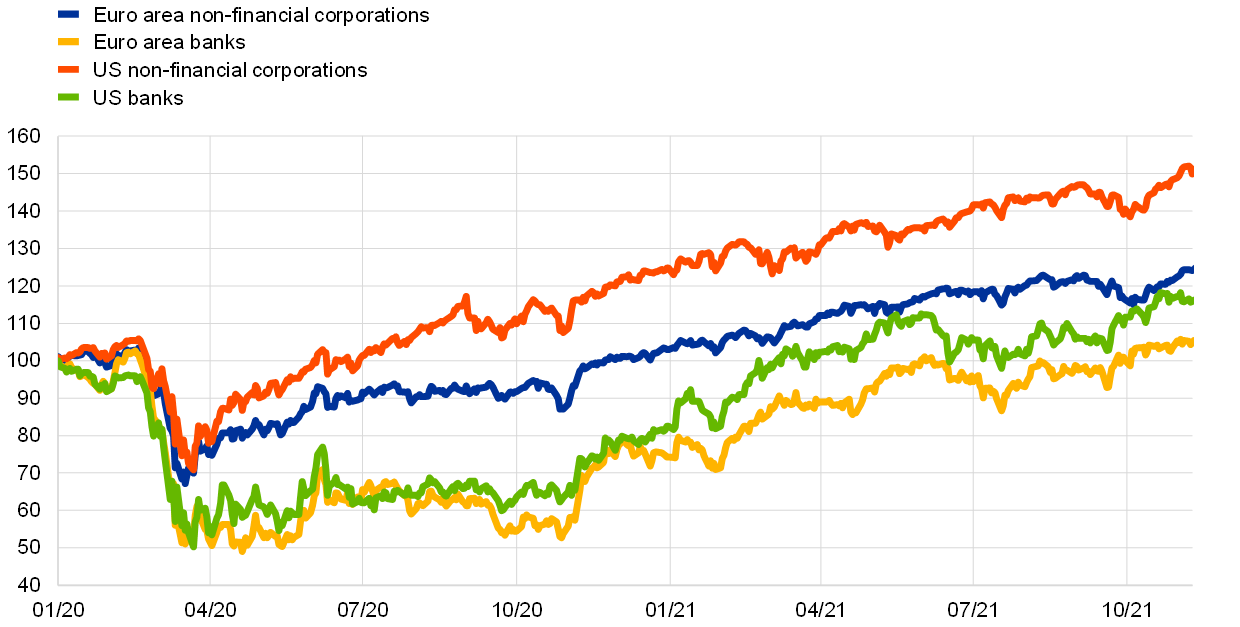

Equity markets supported by long-term earnings expectations

With the ongoing commitment to monetary and fiscal support, the rebound of economic activity in 2021 contributed to a steady increase in equity prices in the euro area, which was driven by very robust and resilient long-term earnings expectations. This trend was temporarily interrupted from mid-September to mid-October, as market expectations of a possible tapering of asset purchases by the Federal Reserve System weighed on the dynamics of stock markets worldwide. At a sectoral level, euro area bank stock prices, which had fallen in 2020, rose significantly faster than non-financial stock prices. The broad index for euro area non-financial corporation equity prices stood on 31 December 2021 at around 19% above end-2020 levels, while the increase in euro area bank equity prices was significantly higher, at more than 30% (see Chart 1.19).

Chart 1.19

Equity market indices in the euro area and the United States

(index: 1 January 2020 = 100)

Sources: Bloomberg, Refinitiv and ECB calculations.

Note: The EURO STOXX banks index and the Refinitiv market index for non-financial corporations are shown for the euro area; the S&P banks index and the Refinitiv market index for non-financial corporations are shown for the United States. The latest observations are for 31 December 2021.

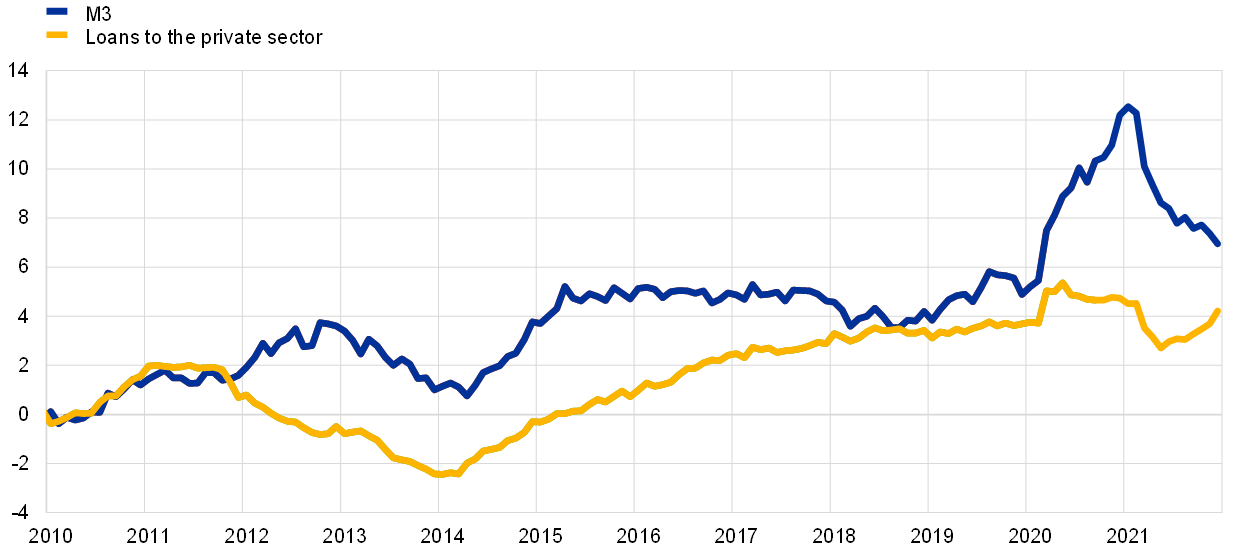

Money and loan growth pointed to a sustained, albeit more moderate, monetary expansion

Broad money growth pointed to a continued robust monetary expansion in 2021. Its pace was closer to the longer-term average than it had been in 2020, i.e. the first year of the pandemic, when it rose sharply (see Chart 1.20). Money creation was driven by the narrow aggregate M1, reflecting a sustained accumulation of overnight bank deposits by firms and households, which was nonetheless more muted than in 2020. In line with the recovery in consumer confidence and spending, household deposit flows returned to their pre-pandemic average. The fact that strong deposit growth in 2020 was not offset by a period of below-average growth suggests a desire to maintain higher savings, as also reflected in the responses to the ECB’s Consumer Expectations Survey. Corporate deposit flows also remained strong, pointing to a further strengthening of liquidity buffers by firms. Eurosystem asset purchases were the largest source of money growth, followed by credit to the private sector. The timely and sizeable measures taken by monetary, fiscal and supervisory authorities during the COVID-19 crisis ensured that the flow of credit to the euro area economy remained at favourable terms.

Chart 1.20

M3 and loans to the private sector

(annual percentage changes, adjusted for seasonal and calendar effects)

Source: ECB.

Note: The latest observations are for December 2021.

Bank lending conditions were supportive overall during the year. The euro area bank lending survey indicated that banks’ credit standards (i.e. internal guidelines or loan approval criteria) for loans to firms and households, which had tightened in the euro area in the previous year, were broadly unchanged starting from the second quarter of 2021. This reflected a reduction in the risks perceived by banks, given the economic recovery and the continued monetary and fiscal policy support, including through loan guarantees. Banks also reported that the ECB’s asset purchase programmes, the third series of targeted longer-term refinancing operations and the negative deposit facility rate had provided support for lending. At the same time, the asset purchase programmes and the negative deposit facility rate were reported to have weighed on their profitability.

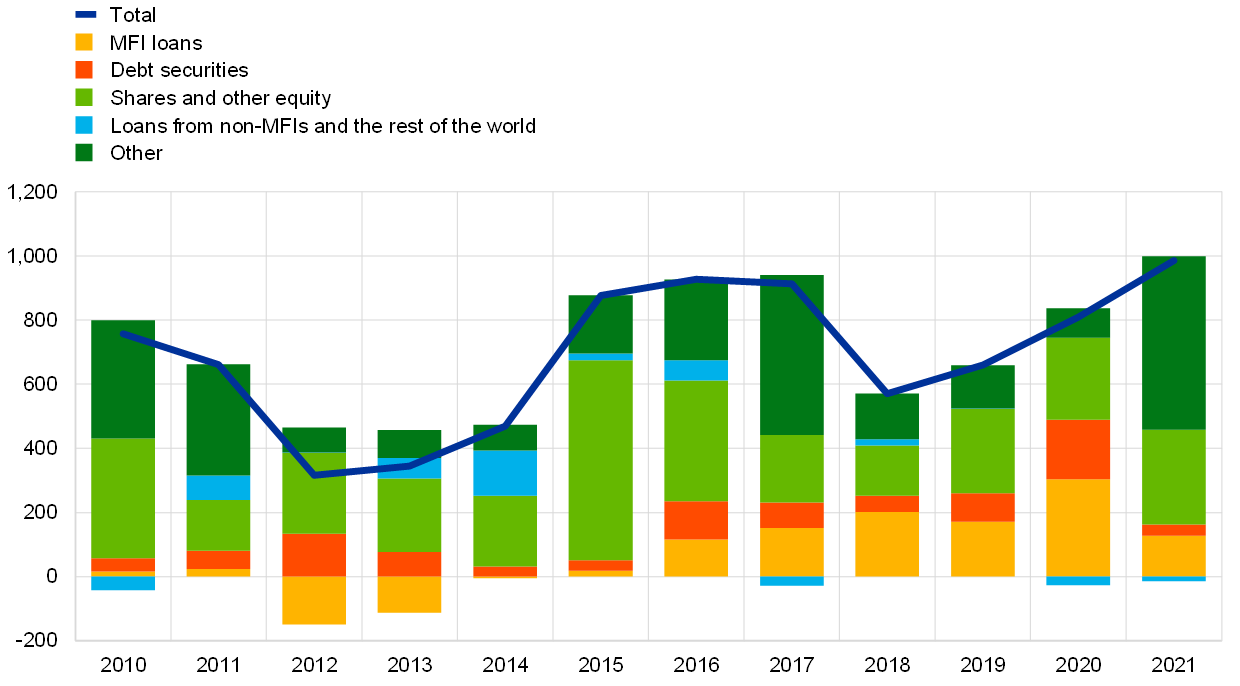

By keeping funding costs for euro area banks low, the policy support measures helped to exert downward pressure on lending rates and prevented a broad-based tightening of financing conditions. During 2021, bank lending rates remained broadly stable around their historical lows. While housing loans grew strongly, consumer credit remained weak as the savings accumulated during the pandemic were available for consumption spending. For firms, the abundant cash reserves, the increase in retained earnings supported by the recent recovery, and the availability of other funding sources – especially inter-company loans and trade credit – reduced borrowing needs. Thus, non-financial corporations’ borrowing from banks and their net issuance of debt securities moderated, after having grown strongly in 2020, despite the real cost of debt financing reaching a new historical low in the fourth quarter of 2021. After 7.1% in the first year of the pandemic, the annual growth rate of bank loans to firms fell back in 2021, to 4.3%, while according to the Survey on the access to finance of enterprises, the share of firms reporting obstacles when seeking a loan declined to pre-pandemic levels. Non-financial corporations were also able to rely on shares and other equity as a means of financing. In total, the external financing flows of non-financial corporations increased further in 2021 (see Chart 1.21).

Chart 1.21

Net flows of external financing to non-financial corporations in the euro area

(annual flows, EUR billions)

Sources: Eurostat and ECB.

Notes: MFI: monetary financial institutions. In “loans from non-MFIs and the rest of the world”, non-monetary financial institutions consist of other financial intermediaries, pension funds and insurance corporations. “MFI loans” and “loans from non-MFIs and the rest of the world” are corrected for loan sales and securitisation. “Other” is the difference between the total and the instruments included in the chart and consists mostly of inter-company loans and trade credit. The latest observations are for the third quarter of 2021. The annual flow for 2021 is computed as a four-quarter sum of flows from the fourth quarter of 2020 to the third quarter of 2021.

2 Monetary policy: continued support and a new strategy

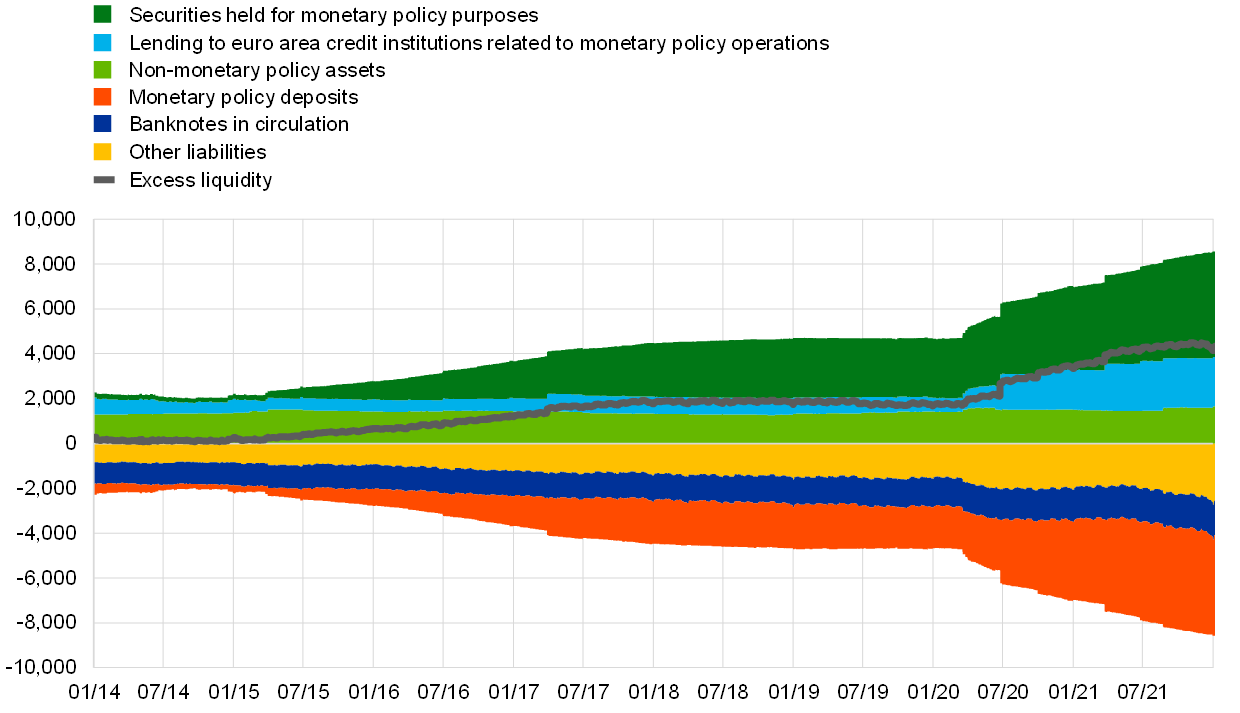

The comprehensive set of monetary policy measures employed by the ECB in 2021 and their recalibrations prevented a procyclical tightening of financing conditions and reduced the threat of a liquidity and credit crunch by keeping ample liquidity in the banking system and protecting the flow of credit to the economy. The monetary policy response was a crucial stabilising force for markets and provided support to the economy and the inflation outlook. The size of the Eurosystem’s balance sheet reached a historical high of €8.6 trillion at the end of 2021, an increase of €1.6 trillion compared with a year earlier. At the end of 2021 monetary policy-related assets accounted for 80% of the total assets on the Eurosystem’s balance sheet. Risks related to the large balance sheet continued to be mitigated by the ECB’s risk management framework.

2.1 The ECB’s monetary policy response continued to provide crucial support to the economy and the inflation outlook

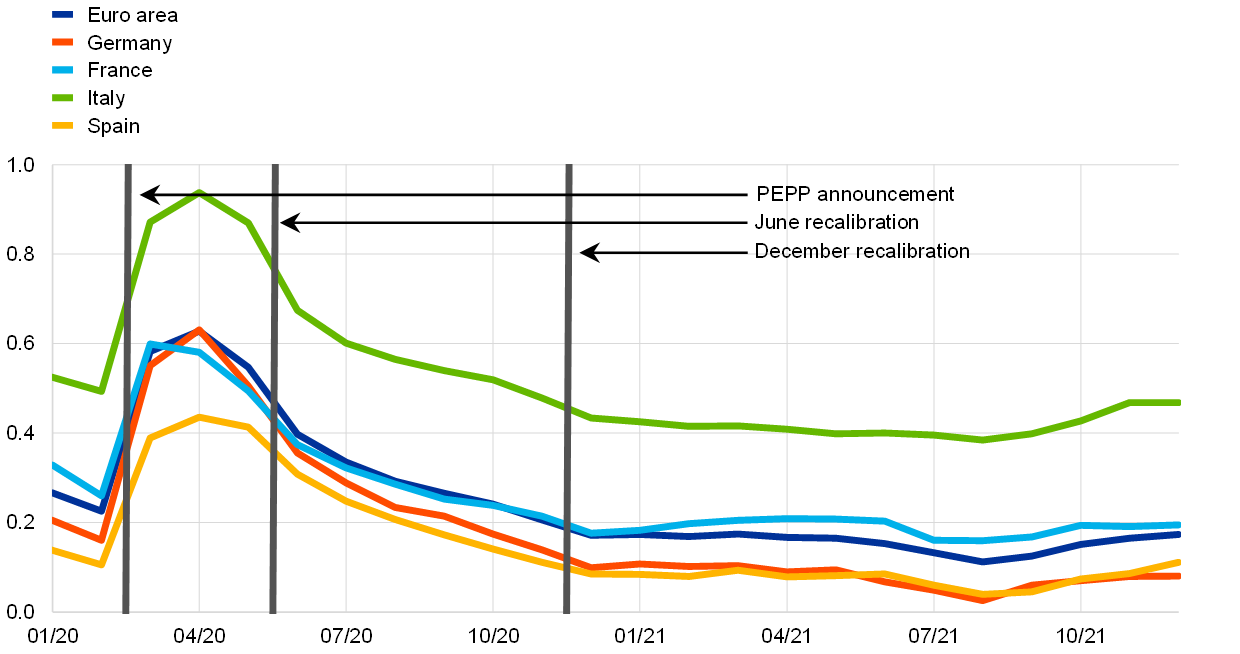

Keeping financing conditions supportive

The pandemic continued to disrupt economic activity at the start of the year and inflation remained very low

At the start of 2021 economic developments in the euro area were still deeply affected by the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. Although the start of vaccination campaigns was a milestone in the fight against the coronavirus, the renewed surge in infections and the emergence of virus variants meant that measures to reduce the spread of the virus needed to be prolonged or tightened in many euro area countries. This disrupted economic activity and clouded the near-term outlook. Inflation remained very low, in a context of weak demand and significant slack in labour and product markets. Overall, incoming data at the start of the year confirmed the Governing Council’s previous baseline assessment that the pandemic would have a pronounced impact on the economy in the near term and that there would be protracted weakness in inflation. In broad terms, financing conditions in the euro area were generally supportive. Although risk-free rates had risen slightly since the Governing Council’s December 2020 meeting, sovereign and corporate credit spreads had been resilient, bond market conditions remained favourable – including for corporate bonds – and bank lending rates were close to their historical lows for both households and firms.

In January the Governing Council confirmed the accommodative monetary policy stance of December 2020

Against this background ample monetary policy support remained essential, and the Governing Council decided in January 2021 to confirm the accommodative monetary policy stance of December 2020 in order to preserve favourable financing conditions over the pandemic period.[19] This was aimed at reducing uncertainty and bolstering confidence, encouraging consumer spending and business investment, underpinning economic activity, and therefore safeguarding medium-term price stability. In particular, the net purchases under the €1,850 billion pandemic emergency purchase programme (PEPP), which had been extended to at least the end of March 2022, contributed to preserving favourable financing conditions for all sectors of the economy, while the third series of targeted longer-term refinancing operations (TLTRO III) remained an attractive source of funding for banks, supporting bank lending to firms and households. The continued reinvestment of principal payments from maturing securities purchased under the PEPP and the continued net monthly asset purchases of €20 billion under the asset purchase programme (APP) also supported financing conditions by signalling a presence of the Eurosystem in the markets over the pandemic period and beyond.

The extension and tightening of containment measures weighed on economic activity in the first quarter but headline inflation rose sharply

While in the early months of the year the spread of virus variants and the associated extension and tightening of containment measures weighed increasingly on economic activity, headline inflation started to rise sharply from negative levels on the back of country-specific and technical factors (including base effects) as well as a marked pick-up in energy prices. Underlying price pressures, however, remained subdued in the context of continued weak demand and significant slack in labour and product markets. Longer-term risk-free interest rates and sovereign bond yields continued the rise seen since the Governing Council’s December meeting. As these market interest rates are the key benchmark rates used in the pricing of other capital market instruments – such as corporate and bank bonds – as well as in the pricing of bank loans to households and firms, shocks originating in these rates tend to influence broader financing conditions at a later stage. A sizeable and persistent increase in market interest rates could therefore translate into a premature tightening of financing conditions for all sectors of the economy. This would have challenged the commitment made by the Governing Council in December 2020 and January 2021 to preserve favourable financing conditions over the pandemic period and to prevent any tightening that was inconsistent with countering the pandemic’s downward impact on the projected inflation path. A tightening of financing conditions would have increased uncertainty and reduced confidence, further curtailing economic activity and endangering medium-term price stability.

The Governing Council increased the pace of PEPP net asset purchases in March after market interest rates rose

In March, as financing conditions had tightened while the inflation outlook had not improved, the Governing Council decided to conduct net purchases under the PEPP in the following quarter at a significantly higher pace than in the first months of the year. The remaining December policy measures were reconfirmed.[20] In April, the pace of net purchases as well as the other measures were left unchanged, as incoming information confirmed the joint assessment of financing conditions and the inflation outlook carried out at the March meeting.

Reopening of the economy and a new strategy

The June Eurosystem staff projections saw inflation increasing in 2021 before declining again in 2022

Towards the middle of the year, the evolution of COVID-19 infections and the progress in vaccination campaigns allowed a reopening of the euro area economy. Despite the emergence of new virus variants, pressure on healthcare systems was abating. The June Eurosystem staff macroeconomic projections for the euro area saw inflation continuing to increase in the second half of 2021, before declining again in 2022 as temporary factors were expected to fade out. Underlying inflation pressures were seen gradually increasing throughout the projection horizon, and projections for the Harmonised Index of Consumer Prices (HICP) excluding energy and food were revised upwards. Headline inflation was, however, still projected to stay below the Governing Council’s aim throughout the projection horizon, and underlying inflation was also projected to stay below 2%. While financing conditions for firms and households remained stable, market interest rates increased further in the period before the Governing Council meeting on 10 June. This was partly due to the improved economic prospects, but any tightening in wider financing conditions was considered by the Governing Council to be premature and a risk to the ongoing recovery and inflation outlook.

Since the outlook for inflation beyond the near term continued to fall short of the medium-term path that had been projected before the pandemic, and amid the risk of tighter financing conditions, the Governing Council decided in June to continue net asset purchases under the PEPP at a significantly higher pace than during the first months of the year and also confirmed all of its other policy measures.

The ECB concluded its monetary policy strategy review in July 2021 and adopted a symmetric inflation target of 2%

On 8 July the Governing Council concluded its monetary policy strategy review (see Section 2.4). The new strategy incorporated two key factors to be reflected in the formulation of the Governing Council’s monetary policy stance: first, the adoption of a new, symmetric 2% inflation target over the medium term; and, second, a conditional commitment to take into account the implications of the effective lower bound when conducting monetary policy in an environment of structurally low nominal interest rates, which would require especially forceful or persistent monetary policy measures when the economy is close to the lower bound. In pursuit of its new target and in line with its monetary policy strategy, the Governing Council therefore revised its forward guidance on the key ECB interest rates at its July monetary policy meeting, tying its policy path to three specific conditions related to the inflation outlook. The Governing Council said that the key ECB interest rates were expected to remain at their present or lower levels until it saw inflation reaching 2% well ahead of the end of the projection horizon, and durably for the rest of the projection horizon, and until it judged that realised progress in underlying inflation was sufficiently advanced to be consistent with inflation stabilising at 2% over the medium term. It said that this may also imply a transitory period in which inflation is moderately above target.

In July the Governing Council confirmed its March assessment, which was consistent with preserving favourable financing conditions

In the run-up to the July meeting market interest rates had declined and financing conditions for most firms and households remained at favourable levels. While inflation had continued to rise, this was largely expected to be temporary, and the outlook for the medium term remained subdued. Economic recovery in the euro area was on track, although the spread of the Delta variant of the coronavirus constituted a growing source of uncertainty. Preserving favourable financing conditions was considered essential to ensure that the economic rebound turned into a lasting expansion and to offset the negative impact of the pandemic on inflation. The Governing Council therefore continued to expect net purchases under the PEPP to be conducted at a significantly higher pace than during the first months of the year. It also confirmed the other policy measures.

Supporting the shift to a solid economic recovery and, ultimately, the return of inflation to the 2% target

The September ECB staff projections included further upward revisions to inflation over the projection horizon

By September the rebound phase in the recovery of the euro area economy was increasingly advanced, with output expected to exceed its pre-pandemic level by the end of the year. The new ECB staff macroeconomic projections for the euro area revised the projections for inflation in 2021 up, owing to the high cost pressures stemming from temporary shortages of materials and equipment, the continued higher than anticipated contribution from energy prices, and the effects of the temporary VAT reduction in Germany between July and December 2020. However, inflation in 2023 was still seen at well below 2%, although it was revised up slightly to reflect the better growth outlook and a faster reduction in the degree of slack in the economy. Market-based measures of inflation expectations continued moving up, and were significantly higher than the pandemic lows, though remaining below the ECB’s medium-term target for HICP inflation of 2%. Financing conditions for firms, households and the public sector remained favourable, with bank lending rates at historical lows.

The Governing Council decided on a moderately lower pace of PEPP net asset purchases from September amid favourable financing conditions and a better medium-term inflation outlook

On the basis of the slight improvement in the medium-term inflation outlook and in view of the prevailing level of financing conditions, the Governing Council judged in September that favourable financing conditions could be maintained with a moderately lower pace of net asset purchases under the PEPP than in the previous two quarters. The Governing Council confirmed its other measures.

As the Governing Council met in October, the euro area economy continued to recover strongly. However, growth momentum had moderated to some extent, particularly as shortages of materials, equipment and labour held back production in some sectors. Inflation continued to rise, primarily because of the surge in energy prices but also as the recovery in demand outpaced constrained supply. Inflation was expected to rise further in the near term, but then decline over the course of the following year. Market interest rates had increased since September. Financing conditions for the economy nevertheless remained favourable, especially as bank lending rates for firms and households remained at historically low levels. The Governing Council therefore reaffirmed its September stance, leaving the net purchase pace of the PEPP and all of its other measures unchanged.

The December Eurosystem staff projections revised up inflation but saw growth slowing in the near term, while over 2022 growth was seen rising and inflation declining

By the end of the year, new pandemic-related restrictions and uncertainty, particularly owing to the emergence of the Omicron variant of the coronavirus, continued shortages of materials, equipment and labour as well as significantly higher energy prices were restraining economic activity. The slowdown in growth in the final quarter of the year and the expectation that this would continue into the first part of 2022 led to the December Eurosystem staff projection for growth in 2022 being revised down. Growth was nonetheless expected to pick up strongly again in the course of 2022. Inflation had continued in November to increase at a higher rate than projected, but was expected to decline over the course of 2022. Market and survey-based measures of longer-term inflation expectations had moved somewhat closer to 2%. This, along with the gradual return of the economy to full capacity and further improvements in the labour market supporting faster wage growth, was expected to help underlying inflation move up and bring headline inflation to the Governing Council’s target over the medium term. The December staff projections for both headline and underlying inflation were therefore revised up compared with September, although, at 1.8% in 2024, they remained below the target for HICP inflation. Financing conditions for the economy remained favourable in December, with market interest rates having stayed broadly stable since the October Governing Council meeting and bank lending rates remaining at historically low levels for firms and households.

In December the Governing Council announced a step-by-step reduction in the pace of asset purchases from the first quarter of 2022, discontinuation of PEPP net purchases at the end of March, and flexible PEPP reinvestments until at least end-2024

At its December meeting the Governing Council judged that the progress on economic recovery and towards the medium-term inflation target permitted a step-by-step reduction in the pace of asset purchases over the following quarters. At the same time, monetary accommodation would still be needed for inflation to stabilise at 2% over the medium term, and the environment of uncertainty underscored the need to maintain flexibility and optionality in the conduct of monetary policy. With this in mind, the Governing Council therefore took the following decisions.

First, the Governing Council expected to reduce the pace of net asset purchases under the PEPP in the first quarter of 2022 and would discontinue net purchases at the end of March 2022.

Second, it extended the reinvestment horizon for the PEPP. The Governing Council expressed its intention to reinvest the principal payments from maturing securities purchased under the programme until at least the end of 2024. In any case, the future roll-off of the PEPP portfolio would be managed to avoid interference with the appropriate monetary policy stance.

Third, the Governing Council emphasised that the pandemic had shown that, under stressed conditions, flexibility in the design and conduct of asset purchases helped to counter the impaired transmission of monetary policy and made efforts to achieve its policy goal more effective. Within the Governing Council’s mandate, under stressed conditions, flexibility would therefore remain an element of monetary policy whenever threats to monetary policy transmission jeopardised the attainment of price stability. In particular, in the event of renewed market fragmentation related to the pandemic, PEPP reinvestments could be adjusted flexibly across time, asset classes and jurisdictions at any time. This could include purchasing bonds issued by the Hellenic Republic over and above rollovers of redemptions in order to avoid an interruption of purchases in that jurisdiction, which could impair the transmission of monetary policy to the Greek economy while it was still recovering from the fallout of the pandemic. Net purchases under the PEPP could also be resumed, if necessary, to counter negative shocks related to the pandemic.

Fourth, in line with a step-by-step reduction in asset purchases and to ensure that the monetary policy stance remained consistent with inflation stabilising at the target over the medium term, the Governing Council decided on a monthly net purchase pace of €40 billion in the second quarter of 2022 and €30 billion in the third quarter under the APP. From October 2022 onwards, net asset purchases under the APP would be maintained at a monthly pace of €20 billion for as long as necessary to reinforce the accommodative impact of the policy rates. The Governing Council expected net purchases to end shortly before it started to raise the key ECB interest rates.

The Governing Council also expressed its intention to continue reinvesting, in full, the principal payments from maturing securities purchased under the APP for an extended period of time past the date when it started raising the key ECB interest rates and, in any case, for as long as necessary to maintain favourable liquidity conditions and an ample degree of monetary accommodation.

The level of the key ECB interest rates and the forward guidance on the future path of policy rates were confirmed.

The Governing Council also said it would continue to monitor bank funding conditions and ensure that the maturing of TLTRO III operations did not hamper the smooth transmission of monetary policy. It would also regularly assess how targeted lending operations contributed to the monetary policy stance. The Governing Council said that, as previously announced, it expected the special conditions applicable under TLTRO III to end in June 2022. It would also assess the appropriate calibration of the two-tier system for reserve remuneration so that the negative interest rate policy did not limit banks’ intermediation capacity in an environment of ample excess liquidity. Finally, the Governing Council once again confirmed that it stood ready to adjust all its instruments, as appropriate, to ensure that inflation stabilised at its 2% target over the medium term.

Accommodative monetary policy and recalibrated measures provided favourable financing conditions and countered the negative impact of the pandemic on inflation

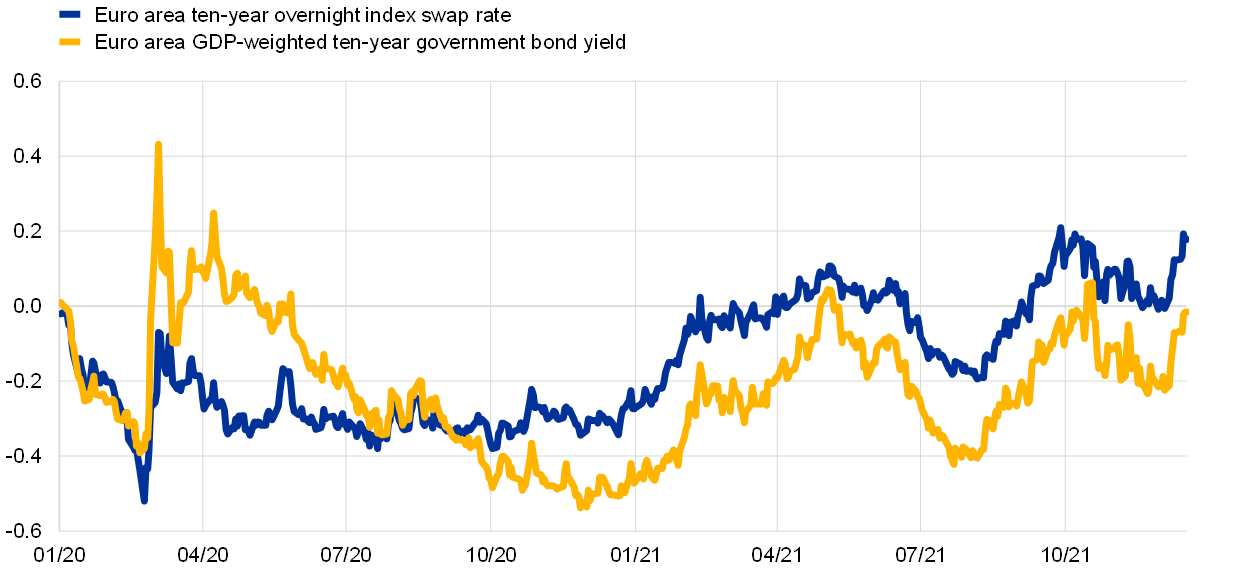

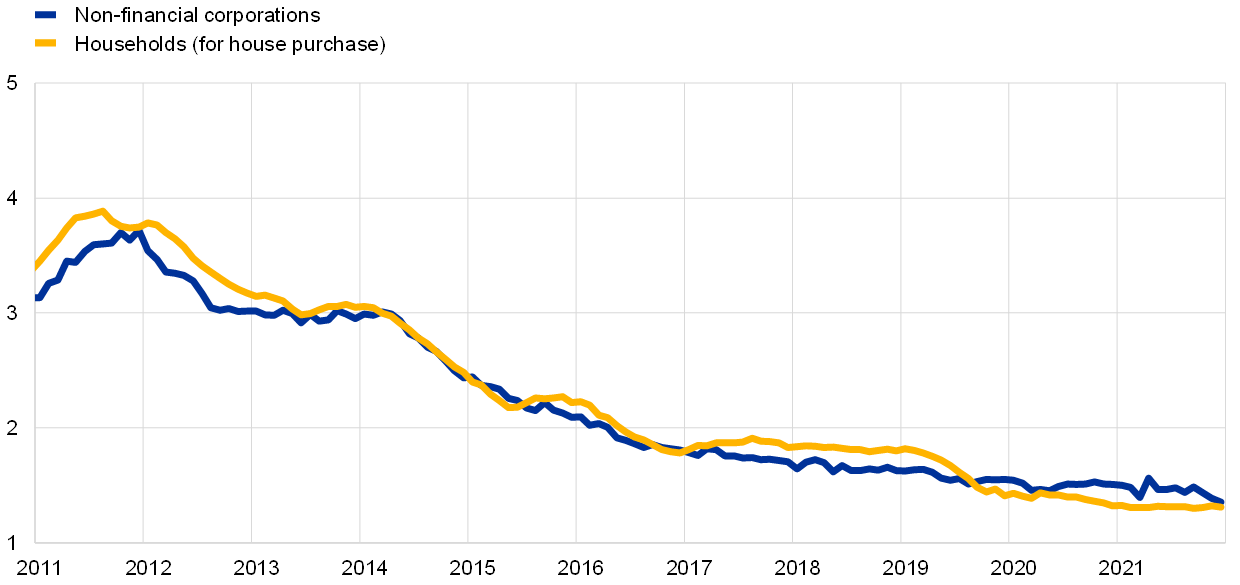

To sum up, substantial monetary policy accommodation was maintained over the course of 2021 to counter the negative impact of the pandemic on the inflation outlook. Recalibrations of the comprehensive set of measures helped to maintain favourable financing conditions. The measures were effective in containing government bond yields (see Chart 2.1), which are the basis of funding costs for households, firms and banks. They also kept bank funding costs very favourable (see Chart 2.2). In addition, they ensured that households and firms benefited from these supportive financing conditions, with the respective lending rates reaching new historical lows and standing at 1.31% and 1.36% for the year (see Chart 2.3). Inflation rose significantly in the second half of the year, while the economy broadly continued on its recovery path. In view of the progress on economic recovery and towards the medium-term inflation target, the Governing Council decided to start a step-by-step reduction in asset purchases from the beginning of 2022. Overall, the monetary policy response in 2021 ensured favourable financing conditions, supporting the continued economic recovery and the convergence of inflation with the Governing Council’s target.

Chart 2.1

Euro area GDP-weighted ten-year government bond yield and ten-year overnight index swap rate

(percentages per annum)

Source: ECB calculations.

Notes: The latest observations are for 31 December 2021.

Chart 2.2

Composite cost of debt financing for banks

(composite cost of deposit and unsecured market-based debt financing, percentages per annum)

Sources: ECB, Markit iBoxx and ECB calculations.

Notes: The composite cost of deposits is calculated as an average of new business rates on overnight deposits, deposits with an agreed maturity and deposits redeemable at notice, weighted by their corresponding outstanding amounts. The latest observations are for December 2021.

Chart 2.3

Composite bank lending rates for non-financial corporations and households

(percentages per annum)

Source: ECB.

Notes: Composite bank lending rates are calculated by aggregating short and long-term rates using a 24-month moving average of new business volumes. The latest observations are for December 2021.

2.2 Continued Eurosystem balance sheet growth as challenges persist

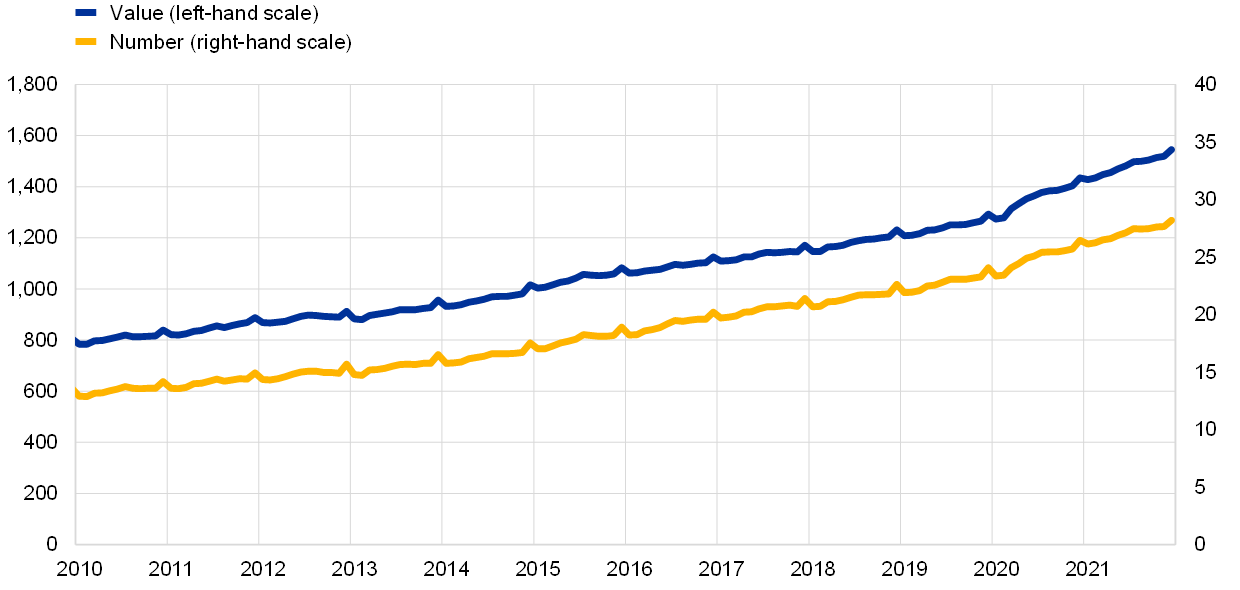

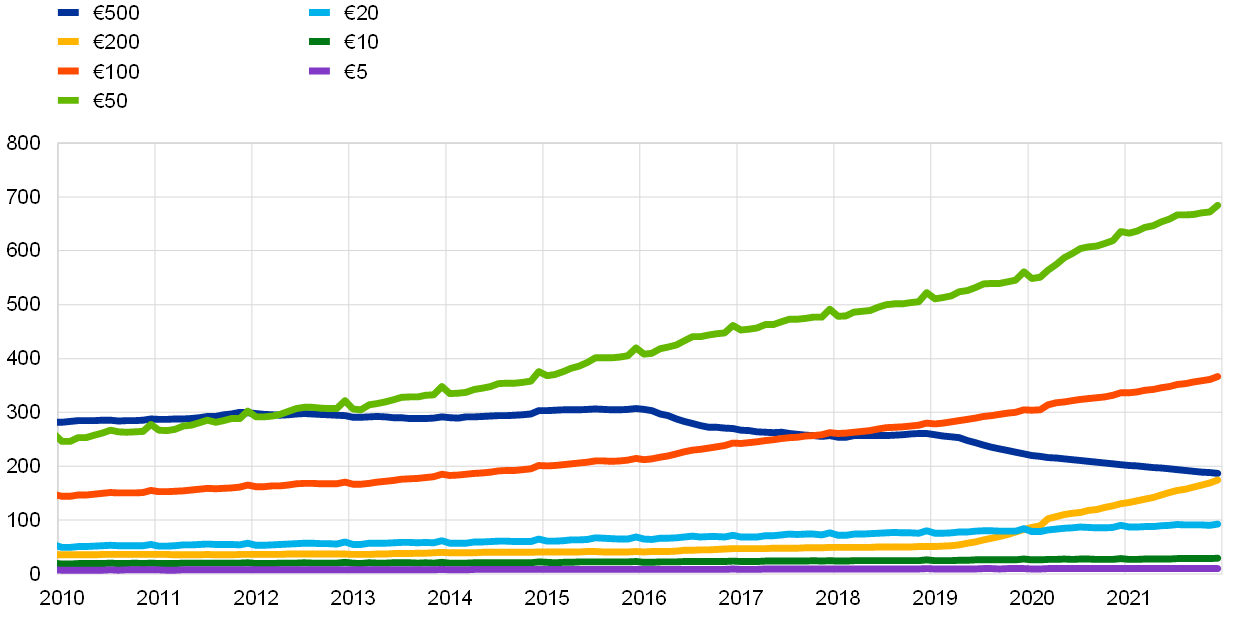

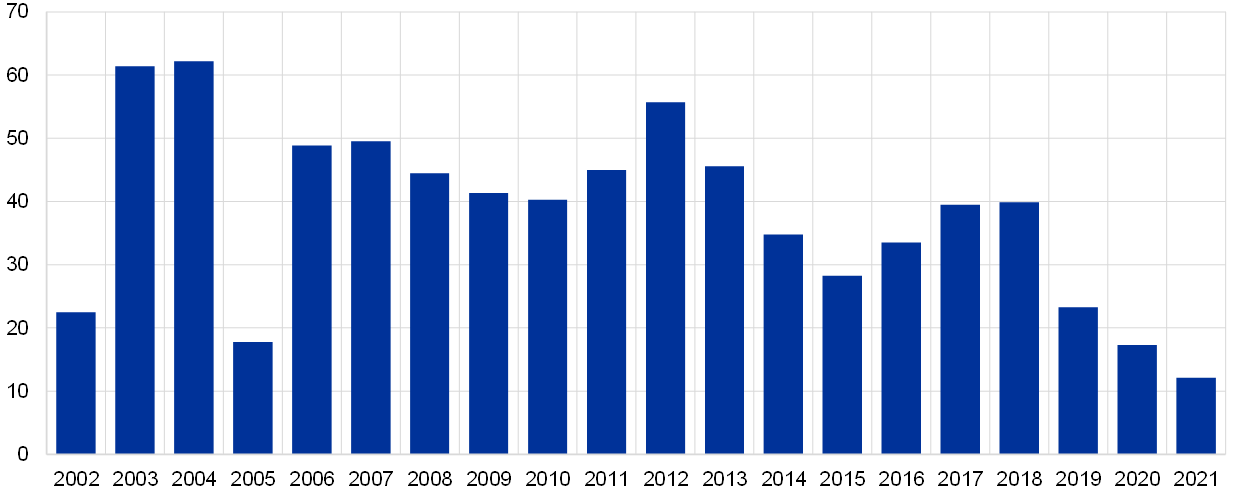

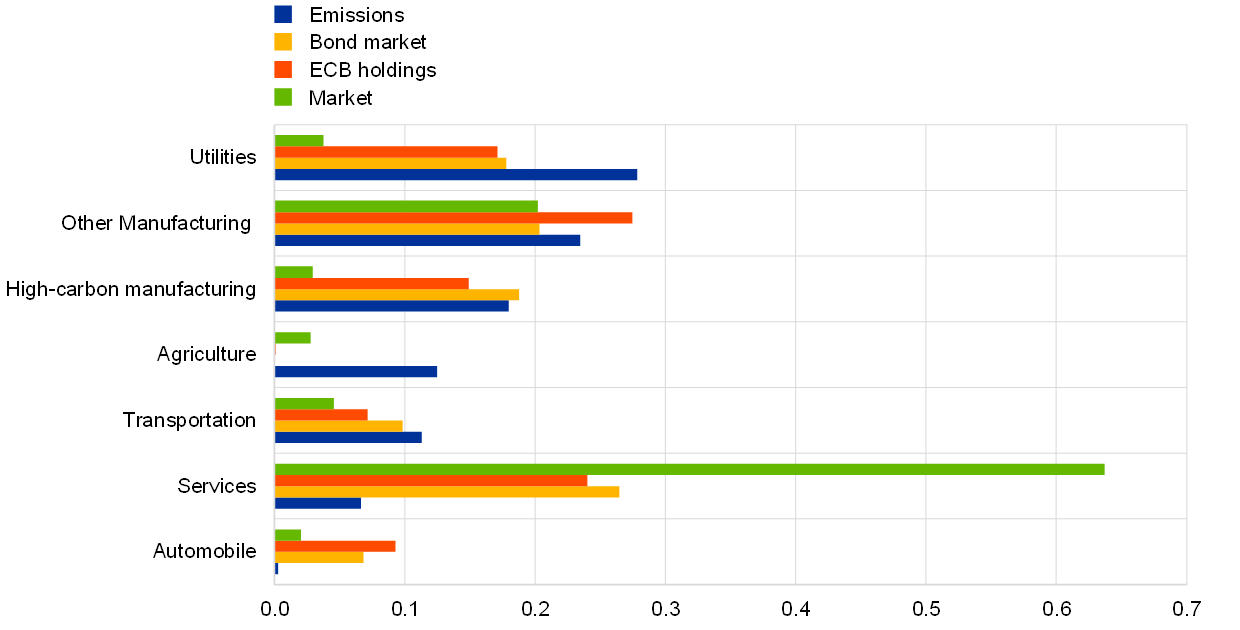

The size of the Eurosystem’s balance sheet increased by 23% in 2021