Bank capital buffers and lending in the euro area during the pandemic

Bank capital buffers and lending in the euro area during the pandemic

Published as part of the Financial Stability Review, November 2021.

Bank capital buffers are supposed to help banks to absorb losses while maintaining the provision of key financial services to the real economy in times of stress. Capital buffers that are usable along these lines should lessen the damaging effects that can arise from credit supply shortages. Making use of buffers entails using the capital space on top of regulatory buffers and minimum requirements and, in case of need, also using regulatory buffers. This special feature analyses bank lending behaviour during the pandemic to gain insights into banks’ propensity to use capital buffers and the impact of the regulatory capital relief measures implemented by the authorities. From a macro perspective, the euro area banking system as a whole was able to meet credit demand and withstand stress. However, this aggregate view reflects several factors, including the impact of extraordinary policy measures. A micro perspective thus can help to comprehend how the capital buffer framework and capital releases affected banks’ behaviour during the pandemic. The microeconometric analysis performed in this special feature shows that the banks that had limited capital space above regulatory buffers adjusted their balance sheets by reducing lending which could be interpreted as an attempt to defend capital ratios. This suggests that they were unwilling to use capital buffers. The results also show that the regulatory capital relief measures adopted during the pandemic, which added to banks’ existing capital space, were associated with higher credit supply. While more research is desirable, also on macro aspects, these findings suggests that more releasable capital could enhance macroprudential authorities’ ability to act countercyclically when a crisis occurs.

1 Introduction

A core goal of the Basel III capital buffer framework is to reduce the amplification effects of the banking system on the economic cycle. The framework envisages that bank capital is built up during periods when credit risk and financial vulnerabilities are increasing. Capital is then employed in case of need to absorb losses and meet credit demand during downturns and crises. Regulatory capital buffers sit on top of minimum capital requirements and constitute the combined buffer requirement (CBR).[1] During downturns, banks can draw on the capital space above the CBR (i.e. management buffers or excess capital) and, in case of need, also the CBR itself, albeit with some limitations, notably the maximum distributable amount (MDA). When dipping into the CBR, banks must compute an MDA that caps the capital they can distribute, for example in the form of dividends, share buybacks or variable remuneration.[2] In addition, to further support the financial intermediation capacity of banks, prudential authorities can release the countercyclical capital buffer (CCyB) or – dependent on the underlying risks – lower other regulatory buffers such as, for example, the systemic risk buffer (SyRB) in periods of distress, which should help to further facilitate the use of the underlying capital.

Concerns have been raised about whether some factors could impair the expected functioning of the framework. Specifically, in periods of economic or financial distress, banks may be unable to draw down the CBR if minimum requirements act as a binding constraint. Furthermore, banks may also be unwilling to dip into the CBR due to a number of factors.[3] These include limitations to distributions that are triggered when capital ratios fall within the CBR[4] and market pressure or stigma associated with the consumption of capital ratios. Ultimately, should impediments to the use of capital buffers affect a large portion of the banking system they can dampen aggregate lending supply to the real economy when most needed, thereby causing the banking system to behave procyclically and amplify a shock via credit supply shortages.

The pandemic offers some insights into the functioning of the capital framework, specifically banks’ propensity to use capital buffers and the impact of regulatory capital relief measures. Banks in the euro area entered the COVID-19 pandemic with relatively strong capital ratios, which were further supported by extraordinary policy measures throughout the pandemic.[5] As a result, the euro area banking system as a whole was able to meet credit demand and withstand stress.[6] Nevertheless, the behaviour of banks with little capital headroom above regulatory buffers (see Chart A.1) offers insights about the propensity of banks to use these buffers, and about the impact of the prudential capital releases which took place in early 2020.[7]

2 Evidence on banks’ behaviour in the proximity of the combined buffer requirement

Differences in banks’ responses, depending on their distance to the CBR, provide a lens through which their willingness to use capital buffers can be assessed. A difference-in-differences analysis allows explicit testing of whether the lending behaviour of a selected group of banks, specifically those with a distance to the CBR smaller than 3 percentage points in the first quarter of 2020,[8] differed significantly from that of banks with larger headroom above the CBR.[9] Bank-level and loan-level data on the corporate loan books of a sample of euro area banks between the second quarter of 2019 and the fourth quarter of 2020 are employed to control for the heterogeneity of bank-specific characteristics and credit demand across firms.[10] Additionally, information on the use of central bank funding (targeted longer-term refinancing operations or TLTROs) by banks and on whether individual loans are under payment moratoria or government guarantee schemes is used to isolate credit supply effects and control for the impact of policy support on lending.[11]

Chart A.1

The distance to the regulatory capital buffers is heterogeneous across banks, but increased during the pandemic on the back of policy actions and de-risking

Sources: ECB supervisory data, ECB market operations database, ECB Statistical Data Warehouse and ECB calculations.

Notes: Panel a: the blue section of the bar corresponds to the difference between the median and the last quartile of the distance to the CBR distribution. The yellow section of the bar indicates the difference between the first quartile and the median of the distance to the CBR distribution. The whisker extends from the upper (lower) quartile to the highest (lowest) decile. Panel b: “High D2CBR” refers to those banks that have a distance to the CBR above the first quartile of the distance to the CBR distribution. “Low D2CBR” refers to those banks that have a distance to the CBR below the first quartile of the distance to the CBR distribution. The trend is normalised so that the variable takes the value of 1 in Q1 2020.

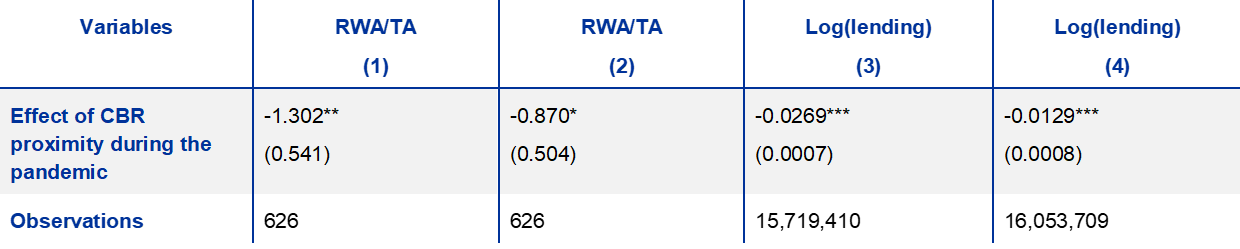

Banks closer to their CBR were found to de-risk their balance sheet and curtail their lending to non-financial corporations (NFCs) more than other banks. Descriptive trends already suggest that banks closer to their CBR reduced their risk weight densities (defined as the ratio of risk-weighted assets (RWA) to total assets (TA)) more strongly during the pandemic than banks further away from it (see Chart A.1, panel b). The econometric analysis further shows that, during the pandemic, proximity to the CBR was associated with a 1.3 percentage point decline in risk weight densities relative to other banks, a material drop compared with an initial risk weight density of 35%. In addition, closer proximity to the CBR was related to lower lending to NFCs by a substantial 2.7 percentage points (see Table A.1). Overall, these results could provide a validation of the concern that banks are reluctant to dip into regulatory buffers.

Table A.1

Estimated impact of proximity to the CBR on bank risk weight density and lending

Sources: ECB AnaCredit data and ECB supervisory data.

Notes: The dependent variables are the risk-weighted assets-to-total assets ratio (columns 1 and 2) and the log of lending volumes (columns 3 and 4). “Effect of CBR proximity during the pandemic” is defined as the product of Low D2CBR and COVID-19. Low D2CBR is a dummy equal to 1 for banks that have a distance to the CBR below the first quartile of the distance to the CBR distribution (corresponding to 3%), 0 otherwise. COVID-19 is a dummy equal to 1 for the period after the pandemic, 0 otherwise. To control for heterogeneity among banks, the panel OLS regressions include a large number of lagged bank-specific control variables (size, profitability, asset quality, solvency and funding structure) as well as fiscal (moratoria and guarantees) and monetary policy (TLTROs) controls. Columns 1 and 4 are based on bank-level (columns 1 and 2) and loan-level (columns 3 and 4) difference-in-differences between the second quarter of 2019 and the fourth quarter of 2020. Standard errors clustered at bank level (columns 1 and 2) and firm level (columns 3 and 4) are reported in brackets. The first column includes bank and time fixed effects, the second bank and country-time fixed effects, the third firm fixed effects, and the fourth industry-location-size fixed effects to control for credit demand. ***, **, * indicate statistical significance at 1%, 5% and 10% respectively.

Lower levels of lending by banks closer to their CBR resulted in greater credit constraints for non-financial firms reliant on these banks. In principle, the effect on individual firms of a reduction in credit supply from banks in the proximity of the CBR could be offset if other banks picked up the slack. In reality, however, firms which are heavily reliant on banks in the proximity of the CBR may struggle to replace existing sources of financing with alternative ones, or to establish new credit relationships, in turbulent times. Firm-level analysis provides evidence of these substitution impediments. Firms exposed to banks in the proximity of the CBR[12] exhibited 5.3% lower borrowing after the onset of the pandemic than firms borrowing mostly from banks with larger capital buffers (see Chart A.2, panel a, left bar). In addition, borrowing from firms which, prior to the pandemic, had only a single relationship with a bank in the proximity of the CBR declined by an additional 1.7 percentage points after the onset of the pandemic (see Chart A.2, panel a, right bar).

In addition, government loan guarantees for NFCs alleviated some of the effects of weaker lending by banks closer to their CBR. Additional regressions[13] show that new lending increases linearly as the distance to the CBR increases. Specifically, a 1 percentage point greater distance to the CBR yielded a 2.6% greater increase in unguaranteed new lending (see Chart A.2, panel b, dotted blue line). At the same time, the analysis shows that lending would have been lower without government loan guarantees and the loss in lending capacity would have been larger for banks closer to the CBR (see Chart A.2, panel b, dotted yellow line).[14] This highlights the important role played by credit guarantee schemes in supporting firms’ liquidity needs and facilitating risk transfer.

Chart A.2

NFCs face tighter credit from banks close to the CBR, although government guarantees soften the effect

Sources: ECB AnaCredit data, ECB supervisory data and ECB calculations.

Notes: Panel a: based on a firm-level analysis. The dependent variable is the logarithmic change in firm borrowing. “Exposed firms” is a dummy variable taking the value of 1 if a firm’s borrowing prior to the pandemic originating from CBR-constrained banks is greater than 75% of total borrowing. “Exposed firms with single bank relationships” is a dummy that takes the value of 1 if a firm has only a single bank relationship, 0 otherwise. 95% confidence intervals are displayed in yellow. To control for heterogeneity among banks, the regressions include a large number of bank-specific control variables, as well as fiscal and monetary policy controls. Panel b: the impact of being x percentage points above the CBR on log credit volume is displayed, distinguishing between guaranteed and non-guaranteed credit. The graph is based on cross-sectional loan-level regressions performed on the four largest European economies (Germany, France, Italy and Spain). The dependent variable is the logarithm of new lending granted after the pandemic (Q2 2020). “No guarantees” describes the relationship between the distance to the CBR and new lending that is not covered by government guarantee schemes. “Guarantees” indicates the relationship between the distance to the CBR and new lending that is covered by government guarantee schemes. The vertical lines indicate the confidence interval at the 95% level.

3 Impact of regulatory capital relief measures on bank lending

The second part of the analysis investigates how regulatory capital relief measures affected credit supply.[15] During the pandemic, the prudential authorities adopted these measures to support banks’ capacity to accommodate possible increases in risk weights and losses without curtailing lending.[16] However, the size of the corresponding reduction in regulatory capital varied across banks because of the heterogeneity in existing capital buffers and the composition of capital.[17]

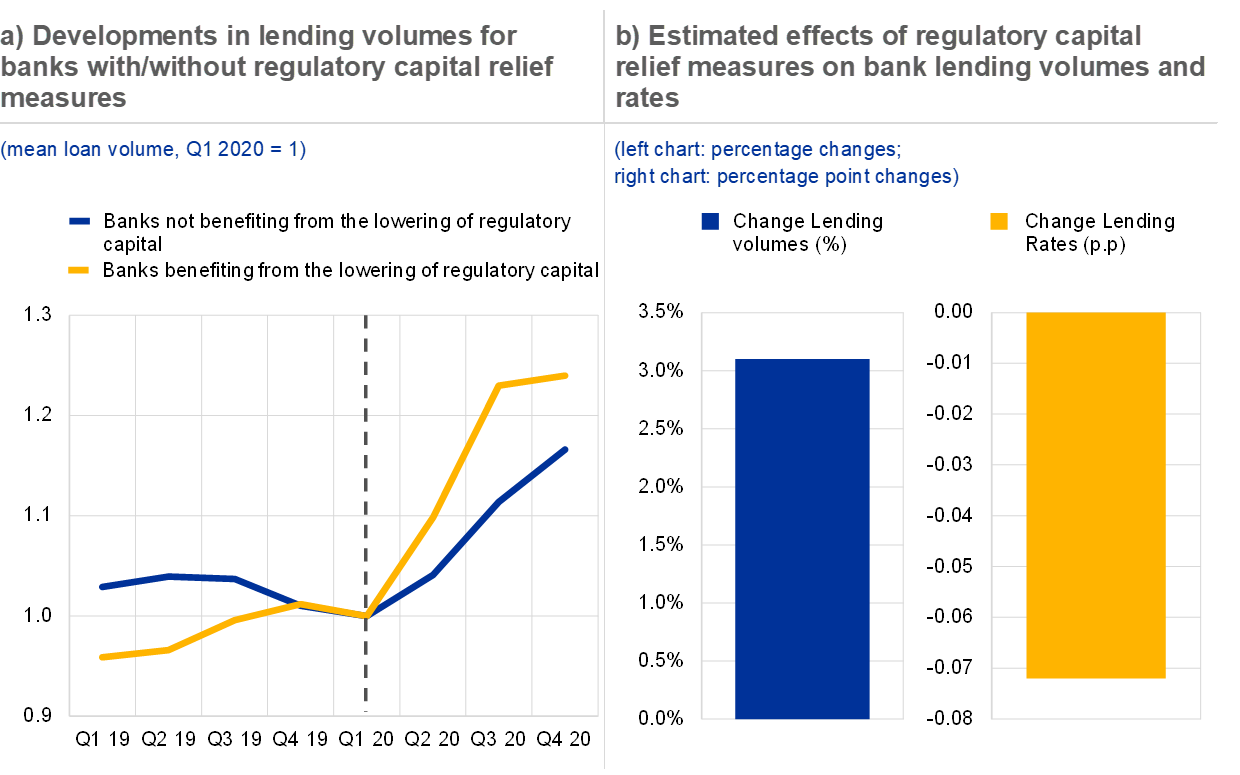

Chart A.3

Regulatory capital relief measures supported bank lending volumes and rates to firms

Sources: ECB AnaCredit data, ECB supervisory data and ECB calculations.

Notes: Panel a: banks benefiting from regulatory capital relief measures took advantage of the frontloading of the change in the composition of the P2R and/or of the release of the CCyB or the reduction of other buffers of the CBR. The trend is normalised so that the variable takes the value of 1 in Q1 2020. Panel b: the estimates are based on loan-level difference-in-differences regressions, after propensity score matching on ex ante bank characteristics. The treatment variable is the dummy CAPREL, equal to 1 for banks benefiting from regulatory capital relief measures. The regressions include – as control variables – bank balance sheet characteristics (including the take-up of central bank liquidity operations) and firm-bank loan-level characteristics to account for loan guarantees and moratoria, as well as fixed effects for the firm and country of the lender bank. Standard errors are clustered at the firm and bank level.

The results show that regulatory capital relief measures had positive effects on lending, especially for banks closer to the CBR. A comparison of the credit trends suggests that – after the policy measures – banks benefiting from lower capital requirements expanded lending volumes more than other banks (see Chart A.3, panel a).[18] A difference-in-differences analysis using firm-bank data on corporate loans to control for credit demand,[19] and accounting for bank-specific characteristics and other concurrent policies, confirms these results.[20] In particular, credit volumes increased by 3.1% after the regulatory capital relief measures, while interest rates on loans to firms eased by 7 basis points (see Chart A.3, panel b). Furthermore, the measures provided capital space to banks which were reluctant to use or get closer to the CBR, thereby supporting the credit supply from these banks (see Chart A.4, panel a).

Small and medium-sized enterprises benefited the most from the regulatory capital relief measures (see Chart A.4, panel b). The measures appear more effective for the provision of credit to those firms more reliant on bank lending, which have typically low or no access to debt securities funding and are thus less able to substitute across funding sources. Such a result is consistent with the objectives of the various policy actions undertaken during the pandemic.

Chart A.4

Stronger expansionary effects for banks closer to the CBR, as well as for SMEs

Sources: ECB AnaCredit data, ECB supervisory data and ECB calculations.

Notes: Based on loan-level difference-in-differences regressions, after propensity score matching on ex ante bank characteristics. The estimates report the coefficients of the interaction between the dummy CAPREL and a dummy for bank-specific characteristics, while the confidence intervals are shown at the 90% level. “Low D2CBR” (“High D2CBR”) is a dummy equal to 1 for banks that have a distance to the CBR below (above) the first quartile of the distance to the CBR distribution. Panel b: large firms are those with more than 250 employees, medium firms more than 50, small firms more than ten and micro firms fewer than ten.

4 Conclusions

The behaviour of individual banks during the pandemic offers some insights into the functioning of the Basel III capital buffer framework, in particular the usability of capital buffers and the impact of regulatory capital relief measures. First, the results show that proximity to the combined buffer requirement (CBR) is associated with contractionary balance sheet adjustments (i.e. lower lending to NFCs) to insulate capital ratios. This could indicate that banks in proximity of the CBR have been reluctant to dip into regulatory capital buffers. While from a macro perspective credit growth has been strong and the euro area banking system has been able to meet credit demand during the pandemic, the behaviour of banks with limited capital space above the CBR could indicate possible impediments to the smooth functioning of the capital framework in periods of economic distress. Second, this special feature finds that regulatory capital relief measures, which increased the capital space above the CBR, had positive effects on the supply of credit by individual banks. This supports the role of the reduction of regulatory capital buffers in mitigating the potentially procyclical behaviour of the banking system in periods of economic distress. From a policy perspective, those results could also suggest that more releasable capital would be desirable to enhance macroprudential authorities’ ability to act countercyclically when a crisis occurs and more banks approach the CBR, insofar as the stability of the system is not jeopardised. However, more research, on macro aspects, is desirable to further test and substantiate this hypothesis.

- The CBR consists of the capital conservation buffer, the countercyclical capital buffer, the systemic risk buffer and the buffers for global and other systemically important institutions.

- The higher the use of the CBR, the lower the distributable amount. Banks must also provide a capital conservation plan, including profit forecasts and intended measures to bridge the gap in capital.

- For an explanation of the factors, see the article entitled “Macroprudential capital buffers – objectives and usability”, Macroprudential Bulletin, No 11, ECB, October 2020.

- As the distributable amount decreases as use of the CBR increases, banks have an incentive to steer away from activating the MDA, so as to maintain discretion over their dividend policies and avoid the associated stigma. See “Macroprudential capital buffers – objectives and usability”, op. cit.

- In June 2020, the EU Council ratified the Capital Requirements Regulation (CRR) “quick fix”, which contained adjustments to the CRR to facilitate lending by banks. First, it extended the International Financial Reporting Standard (IFRS) 9 transitional arrangements to mitigate the capital impact stemming from IFRS 9 expected credit loss provisions. Second, it attributed a preferential treatment to non-performing exposures guaranteed by the public sector. Third, it delayed by a year the leverage ratio buffer applied to globally systemically important institutions. Fourth, it adjusted the leverage ratio to exclude certain central bank exposures. Fifth, it accelerated the application of the revised small and medium-sized enterprise (SME) supporting factor and the infrastructure supporting factor, as well as a few other deductions. Finally, banks benefiting from guarantees granted by national governments or other public entities were made subject to a zero risk weight on the guaranteed portion of the exposure.

- See, for example, Financial Stability Review, ECB, November 2020.

- Starting on 12 March 2020, euro area prudential authorities decided to temporarily reduce buffer requirements, releasing more than €140 billion of Common Equity Tier 1 (CET1) capital held by euro area banks. Specifically, €20 billion originated from the release of macroprudential buffer requirements. The remaining €120 billion stemmed from microprudential and bank-specific capital releases, as banks could partially use additional Tier 1 (AT1) and Tier 2 (T2) capital instruments to meet Pillar 2 requirements (frontloading a measure already foreseen in the Capital Requirements Directive, CRD V) and were allowed to operate below Pillar 2 guidance. As a result, the CET1 management buffer of euro area significant institutions increased by about 1.3 percentage points.

- 3% corresponds to the first quartile of the distance to the CBR distribution before the pandemic. The reliability of the results is tested, also considering variations in the distance to the CBR threshold. To be valid, the difference-in-differences must meet the so-called “parallel trend assumption”, meaning that trends in the outcome variable should move similarly in both the control and the treatment group before the pandemic. This assumption has been tested and validated.

- Since the proximity of the CBR is not completely exogenous as banks closer to the CBR may suffer from weaker balance sheets than banks further away from it, propensity score matching (PSM) difference-in-differences are employed as robustness checks. Banks in the proximity of the CBR show lower profitability and greater asset quality deterioration; hence, the PSM guarantees a more comparable sample of control group banks displaying similar ex ante shock characteristics. In addition, PSM is employed to separate the impact of the CET1 ratio from the distance to the CBR, which is important given the correlation between the two variables. The PSM is performed on variables capturing size, profitability, asset quality, solvency and funding structure. For more detailed information see Couaillier, C., Lo Duca, M., Reghezza, A. and Rodriguez d’Acri, C., “Caution: Do not cross! Distance to regulatory capital buffers and lending in COVID-19 times”, Working Paper Series, ECB (forthcoming).

- The bank-level analysis includes a sample of 110 banks, while 298 banks are employed for the analysis based on the AnaCredit dataset. The existence of multiple bank lending relationships enables the identification of supply-driven shocks because demand factors are captured by the inclusion of firm fixed effects, which requires a multiplicity of lending relationships, following the approach used by Khwaja, A. and Mian, A., “Tracing the impact of bank liquidity shocks: Evidence from an emerging market”, American Economic Review, Vol. 98, 2008, pp. 1413-1442. Since a large number of single-bank relationships involve SMEs, this analysis also employs firm industry-location-size fixed effects. This makes it possible to control for credit demand of firms of the same size in specific industries and geographical areas and to retain single-bank relationships in the estimation (see Degryse, H., De Jonghe, O., Jakovljevic, S., Mulier, K. and Schepens, G., “Identifying credit supply shocks with bank-firm data: Methods and applications”, Journal of Financial Intermediation, Vol. 40, 2019).

- In AnaCredit, it is possible to identify loans that are affected by the above-mentioned policies.

- These are defined as firms receiving at least 75% of their borrowing from banks closer to the CBR before the COVID-19 pandemic.

- These additional cross-sectional regressions include more than 1.5 million newly granted loans in a smaller set of countries including Germany, France, Italy and Spain in the second quarter of 2020. This part of the analysis uses the protection received for each loan contract to disentangle the effect of the distance to the CBR on guaranteed and unguaranteed credit.

- Government guarantees support lending by banks closer to the CBR as the guaranteed portion of the exposure is subject to a zero risk weight.

- The main focus of this special feature is on the role of regulatory capital buffers and on related reductions by authorities. Authorities lowered the capital that was not supposed to be released ex ante due to a lack of releasable buffers. Therefore, the regulatory capital relief measures considered in this analysis include not only the release of the CCyB, but also the ad hoc reduction of the SyRB and other systemically important institution (O-SII) buffers, as well as the frontloading in the change of the composition of the Pillar 2 requirement (P2R). This was a one-off supervisory measure, undertaken to anticipate a legislative change, and was not meant to be used on a cyclical basis. Banks benefiting from capital relief measures are defined as those which were subject to lower CCyB, SyRB or O-SII rates and/or had AT1 and T2 capital in excess of their Pillar 1 requirement which they could use to partially meet their Pillar 2 requirement (P2R), thereby reducing their CET1 requirement.

- Measures complementary to capital relief aimed at preserving the resilience of the financial system during the COVID-19 pandemic include the ECB recommendations urging credit institutions to refrain from distributing dividends or performing share buy-backs.

- For the CCyB and the SyRB, only some national authorities had activated these buffers before the pandemic, while for the change in the P2R composition only some banks had available AT1 and T2 instruments to replace the CET1 capital. So, in the overall sample, out of 371 banks, 211 benefited from at least one form of capital requirement release (P2R and/or CBR). For these banks, the size of the released capital was 0.47% on average, with a median of 0.32% and an interquartile range between 0.06% (25th percentile) and 0.71% (75th percentile).

- An alternative specification expressing the capital requirement releases and the P2G in percentage points (vs dummies in the main specification) confirms those results.

- This approach exploiting the multiplicity of lending relationships in loan-level data also follows the methodology proposed by Khwaja and Mian, op. cit.

- Like the previous analysis, the difference-in-differences estimation is conducted after a propensity score matching, based on pre-COVID-19 bank balance sheet characteristics. The dataset uses loan-level data for 188 banks, including both significant and less significant institutions, and covers a sample period from the second quarter of 2019 to the fourth quarter of 2020, where the pre-COVID-19 period is defined as being from the second quarter of 2019 to the fourth quarter of 2019 and the COVID-19 period is defined as being from the second quarter of 2020 to the fourth quarter of 2020.