Study on the payment attitudes of consumers in the euro area 2022

Foreword

The ongoing digitalisation of the economy affects almost all aspects of our daily lives, including the ways in which we pay. The Eurosystem has a key interest in understanding how the payment landscape is evolving and how citizens in the euro area pay for goods and services, as well as how they pay to each other. Ensuring access to means of payment, cash and cashless, is at the heart of both the Eurosystem’s retail payments strategy and its Cash 2030 strategy.

To get a better understanding of how consumers are changing their payment habits, and to what extent, in 2019 the ECB launched a survey to investigate the payment attitudes and behaviours of euro area citizens. To capture changing payment behaviour in a timely manner, the Eurosystem decided to repeat the survey every two years.

The second of these surveys was launched in 2021 and completed in 2022. This report presents the results and describes the key trends identified in euro area consumer payments. While the move towards cashless payments continues, as the report shows, cash still plays an important role. It remains the predominant payment method at the point of sale and for person-to-person payments. Nonetheless, cashless payments are on the rise, supported by a shift from purchases at the point of sale to online purchases. The rate of increase varies across countries and demographic groups. Taking into account ongoing shifts in the payment landscape, the report sheds light on the perceived availability and costs of instant payments for consumers, and on the ownership and use of crypto assets for payment and investment purposes.

Monitoring these trends closely going forward is important for us, in view of our responsibility for issuing public money (currently in the form of cash, and possibly in the future in the form of a digital euro alongside cash) and promoting the smooth functioning of payment systems. This will help us ensure that means of payment remain accessible to all euro area citizens, regardless of their age, income or place of residence, guaranteeing consumers’ freedom to choose how they pay, even in a time of digital transformation.

Fabio Panetta

ECB Executive Board Member

Executive summary

Following on from the first Study on the payment attitudes of consumers in the euro area (SPACE) in 2019, the European Central Bank (ECB) has now conducted a second one. This report presents the key findings from SPACE 2022 and compares them with the results of the 2019 study and, where relevant, with an earlier ECB study conducted in 2016, the Study on the use of cash by households in the euro area (SUCH). When interpreting the 2022 results it is important to note that while no major lockdowns were in place in most euro area countries during the fieldwork periods, the payment behaviour of consumers was still affected by various measures related to the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic – both before and between the survey rounds. These led to restricted entry and even closure of some points of sale, such as restaurants and venues for culture and entertainment, in some Member States.

The SPACE 2022 results show that:

- Cash was the most frequently used payment method at the point of sale (POS) in the euro area and was used in 59% of transactions, down from 79% in 2016 and 72% in 2019.

- Card payments were used in 34% of POS transactions, up from 19% in 2016 and 25% in 2019.

- Other payment methods were used for 7% of POS transactions.

- The share of payments using mobile apps increased from less than 1% in 2019 to 3% in 2022.

- In terms of value of payments, cards (46%) accounted for a higher share of transactions than cash payments (42%). This contrasts with 2016 and 2019, when the share of cash transactions was higher than the share of card transactions (54% compared to 39% in 2016 and 47% compared to 43% in 2019).

- Contactless card payments at the POS increased considerably in three years, from 41% of all card payments in 2019 to 62% in 2022.

- Cash was most frequently used for small value payments at the POS, in line with previous comparable surveys. For payments over €50, cards were the most frequently used method.

- Cash was the dominant means of payment in person-to-person (P2P) transactions in the euro area. However, its share in the total number of payments declined from 86% in 2019 to 73% in 2022, and from 65% to 59% in terms of value.

- Cashless means of payments, particularly mobile phone apps, increased in P2P payments. Between 2019 and 2022, the share of mobile payments more than tripled in terms of number from 3% to 10%, and rose from 4% to 11% in terms of value.

- The share of online payments in consumers’ non-recurring payments increased from 6% in 2019 to 17% in 2022.

- Online payments were used especially for buying food and daily supplies from supermarkets and restaurants.

- The large majority of recurring payments were made using either direct debit or credit transfers.

- In the SPACE 2022 questionnaire, 55% of euro area consumers expressed a preference for cards and other cashless payments when paying in a shop, while 22% preferred cash and 23% had no clear preference.

- Nevertheless, the majority of euro area consumers considered having cash as a payment option to be important or very important.

- The perceived key advantages of cards were that consumers don’t have to carry cash with them, coupled with the convenience of contactless payments.

- The perceived key advantages of cash were its anonymity and protection of privacy and the perception that it makes one more aware of one’s own expenses.

- Compared to before the outbreak of the pandemic, the majority of consumers (54%) said there had been no change in how often they use cash at physical points of sale; 31% of consumers indicated that they were using cash less often and 14% more often.

- For those who reported using cash less often, the most frequently mentioned reason was that paying electronically has become more convenient.

- Cash withdrawals were mostly made from automated teller machines (ATMs), which account for 74% of all cash withdrawals. The use of own cash reserves accounted for 11% and withdrawals over the bank counter for 6%.

- Most euro area consumers were satisfied with their access to cash. The vast majority of consumers (90%) found it fairly easy or very easy to get to an ATM or a bank (up from 89% in 2019). The remaining 10% said it was fairly or very difficult.

- 37% of consumers kept cash reserves at home, outside the wallet or a bank account, up from 34% in 2019.

- Cash was accepted in 95% of physical payment locations throughout the euro area, down from 98% in 2019.

- In the euro area it was possible to pay with non-cash instruments in 81% of transactions in 2022.

Introduction

The way consumers in the euro area pay and the payment instruments they prefer are constantly evolving. Monitoring payment methods on a continuous basis makes it possible to capture changes in consumer demand and market trends.

The Study on the use of cash by households in the euro area (SUCH)[1] was the first payment behaviour survey conducted by the ECB, back in 2016. Results from SUCH are only comparable to the SPACE studies to a limited extent because the survey modes were different and the output variables only partially overlap. The first study on payment attitudes of consumers in the euro area (SPACE)[2] was conducted in 2019 and will be followed up by comparable surveys on a biannual basis.

The results from the SPACE survey make it possible to estimate the share of different payment instruments used by consumers at the point of sale (POS),[3] for person-to-person payments (P2P),[4] online and for recurring payments[5] in various ways, including by demographics and payment patterns. In addition, the surveys give an insight into consumers’ access to and acceptance of cash and other means of payment.

Compared to the 2019 survey, SPACE 2022 additionally looked at: (i) changes in payment behaviour since the onset of the pandemic; (ii) recent trends in digital payments, such as the availability and perceived cost of instant payments; (iii) crypto assets, including information on respondents’ ownership and usage patterns. The results should also serve to better illustrate consumers’ preferences for cash holdings.

1 Summary of research methodology

Data for SPACE 2022[6] were collected through a survey of a random sample of the population in all euro area countries. The most important methodological choices – such as the survey mode, sampling strategy and weighting methodology – were identical to SPACE 2019, making the results of most indicators comparable. A detailed description of the methodologies used is available in a separate document[7] This section briefly summarises the methodology.

The ECB coordinated the data collection in 17 euro area countries, i.e. all except Germany and the Netherlands. The Deutsche Bundesbank (2022) and De Nederlandsche Bank and the Dutch Payments Association (2022) collected their own data with questionnaires harmonised to a large extent with the one used in the other countries.

The data for all countries except Germany and the Netherlands were collected using an identical questionnaire translated into national languages. The market research company Kantar Public was responsible for data collection. 50% of the interviews were collected in computer-assisted telephone interviews (CATI) and 50% in computer-assisted web interviews (CAWI). The CATI sample was drawn with probabilistic methods, while the CAWI sample was drawn from non-probabilistic Kantar Public online panels. For both samples, quotas for country, age, gender and day of the week were set. The total sample size achieved in the 17 euro area countries was 39,765 respondents.

The interview process consisted of three parts: a recruitment interview, the recording period and the main (follow up) interview. The payment diary was split into modules covering (i) POS payments, (ii) P2P payments, (iii) online payments and (iv) recurring payments. Survey respondents were asked to report their POS, P2P and online transactions in a one-day diary, and their recurring payments from the past 30 days.[8]

When interpreting the survey results it is important to recognise the benefits and caveats of recording payment behaviour in one-day diaries. Transactions are recorded more comprehensively in diaries covering one day than those with a period of several days (Jonker and Kosse, 2013). However, the degree of uncertainty involved in any survey data is more pronounced in one-day diaries, especially for drawing conclusions on countries and other subgroups of the population with small sample sizes. Data from a longer diary period include more transactions per sample unit and consequently increase the precision of the estimated indicators (Schmidt, 2014). In particular, indicators on the value of POS and online payments need to be interpreted with care.

In addition to the diary, respondents were asked questions about their behaviour and attitudes to cash and cashless payment instruments in the main interview. Further questions aimed to understand which financial products were available to them, the extent of their access to the internet and how the pandemic had impacted their payment behaviour.

SPACE 2022 interviews were conducted in two survey rounds. During the first, between 2 October and 7 December 2021, 40% of interviews were carried out; the remaining ones were held in the second round, between 17 March and 9 June 2022. The survey rounds were spread across different months of the year to cover various periods and capture seasonal patterns in peoples’ payment behaviour (see Table 1).[9]

In Germany the data were collected in one survey round between 8 September and 5 December 2021. In contrast to the ECB data collection, the German participants were asked to complete a three-day diary. In the Netherlands the diary data and main questionnaire were collected for different samples; the diary data were collected in the fourth quarter of 2021 and the data for the main questionnaire in the first quarter of 2022.

After the fieldwork period the data were cleaned, edited, and imputed.[10] The sample was weighted to minimise the observable bias of survey estimates and enable solid inferences to be made based on the demographic characteristics.

The report includes figures from SUCH 2016 and SPACE 2019 when comparison with SPACE 2022 results is deemed practical and the data are comparable. In addition, after the first iteration of SPACE data collection in 2019, the ECB collected information on the impact of the early phases of the pandemic in a separate survey (the survey on the impact of the pandemic on cash trends or IMPACT survey). Some results of that survey were included in SPACE 2019 and are referred to in this report.

For time series comparisons the payment diary data from 2016 and 2019 were adjusted for inflation. For each country, one price adjustment factor per year was applied.[11] Most of the 2019 data are comparable with the 2022 data. However, due to a change in the definition of online payments between 2019 and 2022,[12] online purchases paid with cash or bank cheques in the 2019 data have been re-classified as POS payments.[13]

Table 1

Breakdown of sample by country, round and month (euro area 17)

2 Trends in payment habits

Two major trends in the way consumers pay for their daily non-recurring payments between 2019 and 2022 have been identified. First, online payments[14] have become more frequent. Second, the share of cash payments at the POS has declined. The less frequent use of cash was already identified in 2019 and the pandemic probably accelerated both trends.

Even though no major lockdowns were in place in most euro area countries during the fieldwork periods,[15] the payment behaviour of consumers was still affected by various measures related to the pandemic. However, it is still uncertain whether this tendency will continue at the pace observed over the past three years, or return to its pre-pandemic path once certain causes inherent in the pandemic cease to apply.

2.1 Change in the breakdown of non-recurring payments

Non-recurring day-to-day payments consist of payments made to purchase goods and services at the physical point of sale, P2P payments not connected to the purchase of goods and services and online payments. Online payments were defined as goods and services ordered and paid for online. However, goods ordered online but paid while picking up the goods or to the courier delivering the goods were defined as POS payments.

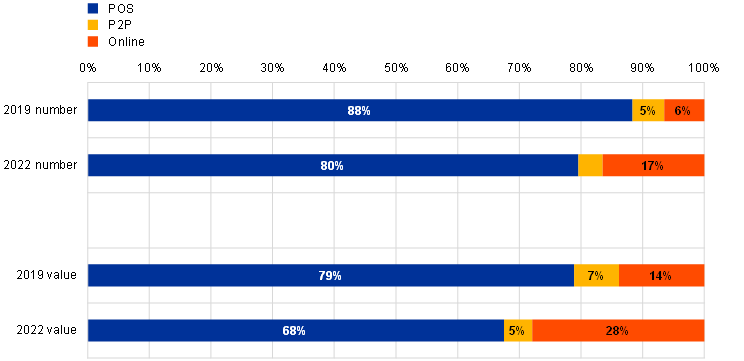

The share of online payments in consumers’ non-recurring purchases increased considerably between 2019 and 2022 in the euro area. Even though there were no major lockdowns in most euro area countries during the fieldwork periods of the latest SPACE survey, those experienced between the data collection periods may have changed the behaviour of some consumers and made them better acquainted with purchasing goods and services online. As shown in Chart 1, of all day-to-day payments, 17% were made online in 2022, compared with only 6% in 2019. In terms of value, the share of online payments in 2022 was 28% (up from 14%), indicating that online payments were more frequently used for larger payment amounts.

The share of the number of P2P transactions in non-recurring payments declined slightly, down from 5% to 4%. The change in the value of P2P payments declined a little more, from 7% to 5%.

Chart 1

Number and value of non-recurring payments by payment situation, 2019 – 2022, euro area

(percentages)

Sources: ECB, calculations based on De Nederlandsche Bank and the Dutch Payments Association (2020, 2022) and Deutsche Bundesbank (2018, 2022).

Note: Percentages may not add up to 100% due to rounding.

2.2 Use of cash is declining, but remains most important at the POS

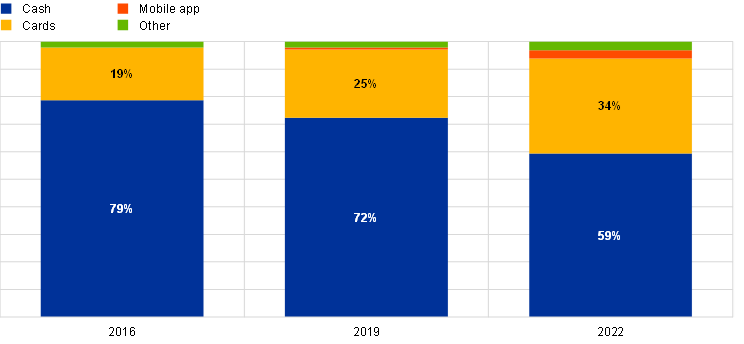

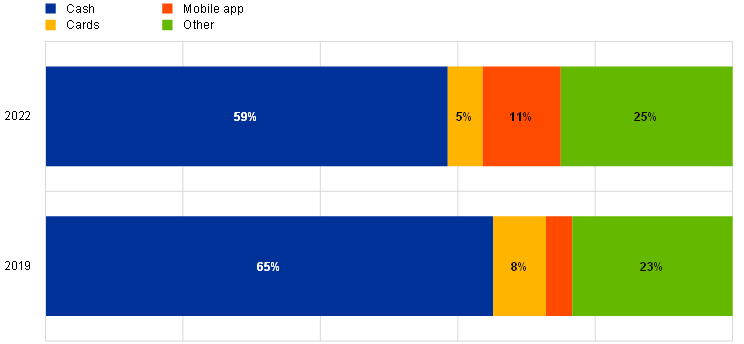

The share of cash payments at the point of sale[16] in terms of volume has declined in recent years. This decline accelerated during the pandemic. In 2022, 59% of transactions were carried out using cash. Three years earlier the share of cash transactions was 72%; in 2016 the figure was 79%. However, cash remained the most frequently used method for payments at the POS in the euro area.

When measuring POS transactions in terms of value, the share of card transactions in 2022 (46%) was higher than the share of cash transactions (42%) for the first time. In 2019 the share of cash transactions by value was 47% and the equivalent share of card transactions 43% (Chart 2).

Consumers were making payments using mobile phone apps more often than before. However, their share in total POS payments was still relatively low compared to cash and card payments. Mobile phone payments accounted for 3% of the number of transactions in 2022 (up from 1% in 2019) and 4% of the value (up from 1%).

Chart 2

Share of payment instruments used at the POS in terms of number and value of transactions, 2016-2022, euro area

(percentages)

Number of transactions

Value of transactions

Sources: ECB, calculations based on De Nederlandsche Bank and the Dutch Payments Association (2020, 2022) and Deutsche Bundesbank (2018, 2022).

Notes: “Other” includes bank cheques, credit transfers, loyalty points, vouchers and gift cards and other payment instruments. Percentages may not add up to 100% due to rounding.

Box 1

The impact of the coronavirus (COVID-19) on payment behaviour

A trend of decreasing cash payments was observed even before the pandemic broke out. The expectation was that this would continue or even accelerate as a result. Lockdowns of varying degrees, recommendations by public authorities and shops to avoid using cash and better availability of card and mobile payments may all have contributed to the decline in cash use. To evaluate the impact of the pandemic, respondents were asked to assess how and why they had changed their payment habits compared to two or three years earlier, before it broke out.

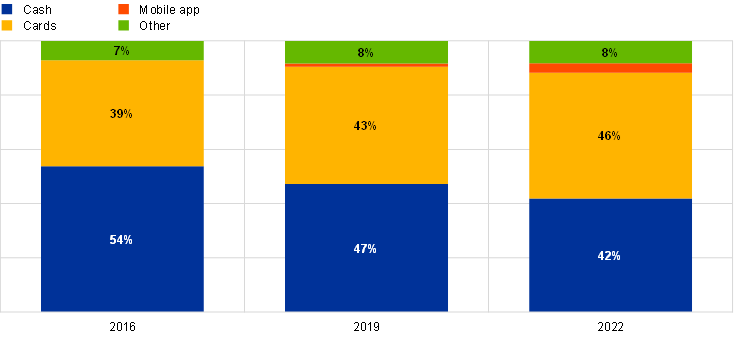

Chart A shows that more than half of consumers (54%) did not change their payment behaviour with regard to using cash at physical locations due to the pandemic. 31% said that they used cash less often than before the pandemic and 14% said they used it more often. These personal assessments are in line with the changes observed in the share of cash transactions at the POS.

Chart A

Share of consumers using cash at physical points of sale more often, less often or equally often compared to before the pandemic, euro area

(percentages)

Sources: ECB, calculations based on De Nederlandsche Bank and the Dutch Payments Association (2022) and Deutsche Bundesbank (2022).

Note: The survey question was: “Compared with the situation two years ago [three in the second survey round] before the coronavirus pandemic, are you using cash instead of non-cash payment methods more or less often for your payments in physical locations (shops, restaurants, etc.)?”

For those who reduced their use of cash during the pandemic, the most frequently reported reason (mentioned by more than half) was that paying electronically has been made more convenient. Advice not to pay with cash (42%) and government recommendations (29%) ranked second and third (see Chart B). About one in four respondents indicated that fear of virus infection was the reason for their less frequent cash use, a much lower share than observed in the IMPACT survey at the beginning of the pandemic (European Central Bank, 2020). The fading fear of virus infections from cash (a fear that has been shown to be mostly unfounded in recent microbiological studies, see Tamele et al, 2021) shows that some behavioural patterns caused by the pandemic have diminished. Consequently, the changes in payment habits experienced over the past few years may prove temporary if the remaining causes cease to apply once the pandemic is over or the virus becomes endemic.

Chart B

Reasons for using less cash during the pandemic given by consumers who said they did so less often than before the pandemic, euro area

(percentages)

Sources: ECB, calculations based on De Nederlandsche Bank and the Dutch Payments Association (2022) and Deutsche Bundesbank (2022).

Note: The survey question was: “Which of the following reasons best explain why you now make cash payments less often than before the coronavirus pandemic?”

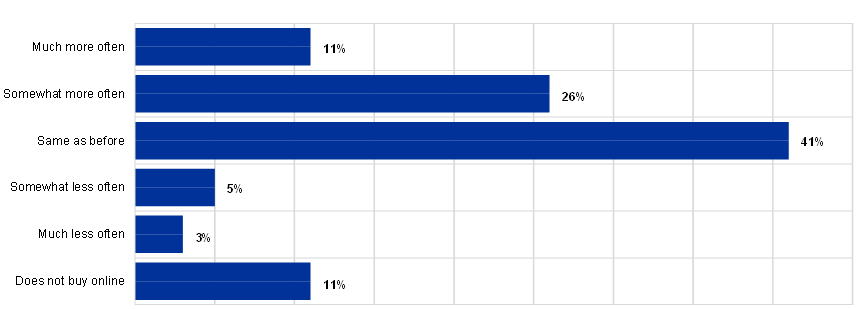

The impact of the pandemic on online shopping was more pronounced than on cash use at the POS, albeit with the opposite sign. As shown in Chart C, 37% of consumers were buying goods online more often than before the pandemic and 41% said there had been no change. Only 8% bought goods online less often than before the pandemic and 11% said they never buy goods online. The reported increase in online shopping was also apparent in the results on the breakdown of non-recurring payments, where there was a significant increase (see Section 2.2.1).

Chart C

Share of consumers making online purchases more, less or equally often during the pandemic, euro area

(percentages)

Sources: ECB, calculations based on De Nederlandsche Bank and the Dutch Payments Association (2022) and Deutsche Bundesbank (2022).

Notes: The survey question was: “Compared with the situation two years ago [three in the second survey round] before the coronavirus pandemic started, are you buying goods online more or less often?”. The chart does not include the 3% of the population who responded “Don’t know”.

3 Payment behaviour by payment situation

Of all non-recurring payment transactions in 2022, 80% were POS, 17% online and 4% P2P. The share of POS in terms of value was approximately two-thirds. Pronounced differences in the breakdown of payment instrument use can be observed from these differing payment situations.

3.1 Share of online payments in non-recurring payments

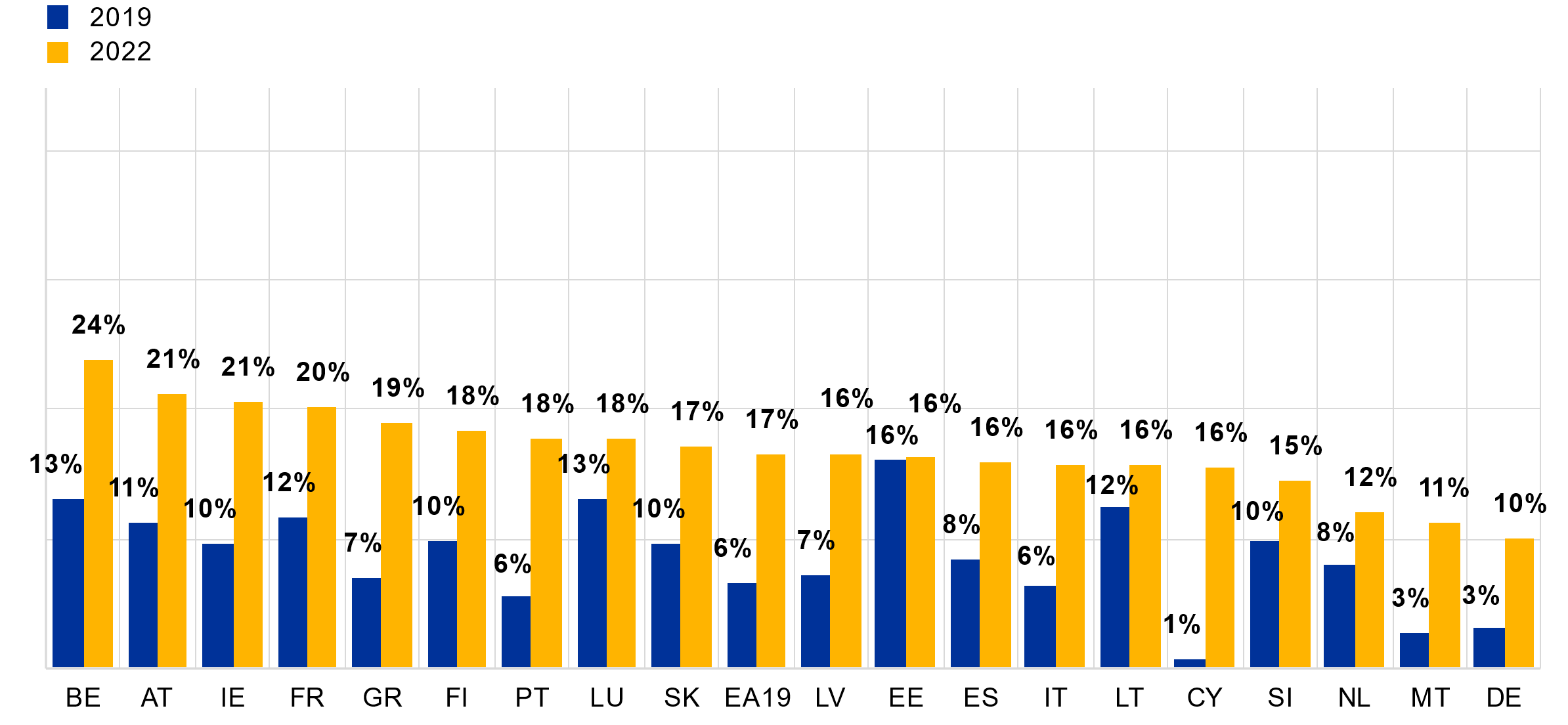

As seen in Box 1, self-assessment information provided by consumers suggests they increased their online shopping during the pandemic. This change was also reflected in the data on actual payment behaviour in every euro area country (Chart 3). Online payments have become more frequent in comparison to POS and P2P across the euro area. In 2022, at least 10% of all non-recurring transactions were online payments in every euro area country. This is a notable change, given that online payments accounted for less than 5% of non-recurring payments in Malta, Cyprus and Germany in 2019. In several countries the share of online payments in 2022 was over 20%, the highest values being reported in Belgium (24%), Austria and Ireland (both 21%) and France (20%).

Online payments were more frequently made for larger-value purchases. The share of online payments was higher in terms of value than number. The highest shares of online payments by value were reported in Slovenia (40%), Finland (37%), Belgium (36%) and Austria (35%).

Chart 3

Share of online payments in consumers’ non-recurring transactions in terms of number and value of transactions, 2019-2022, by country

(percentages)

Number of payments

Value of payments

Sources: ECB, calculations based on De Nederlandsche Bank and the Dutch Payments Association (2020, 2022) and Deutsche Bundesbank (2018, 2022).

Note: EA19 refers to the euro area (19 countries).

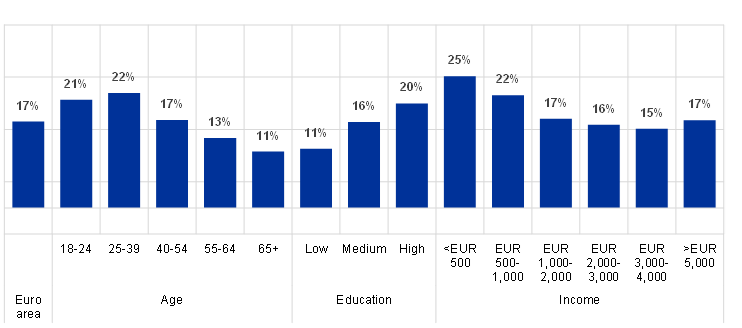

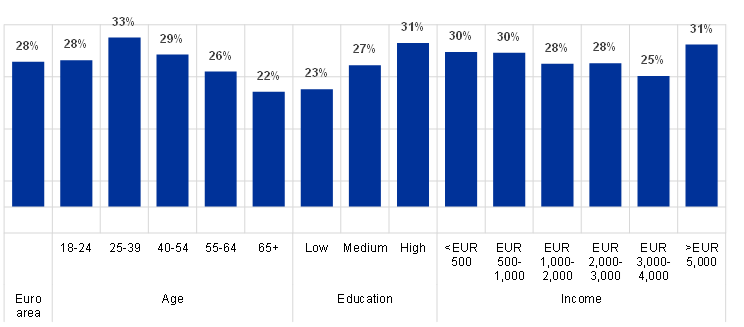

Chart 4 shows that the share of online transactions in non-recurring payments decreases by age, except for those aged 18-24, who made slightly fewer online purchases than those aged 25-39. The reason for this may be that consumers under the age of 24 have less frequent access to payment accounts than other age groups (see Chapter 8.2). Comparing young adults (25-39) to those aged 65 and older, the share of online payments falls from 22% to only 11%. However, people in the latter age group made more online purchases than three years ago.

The share of online shopping was also significantly higher for consumers with higher education. Improvements in the market for online shopping have enabled consumers with sufficient technological literacy to conduct more price arbitrage for their non-recurring payments. The relationship between household income and online purchases is not straightforward. When measured in terms of number of payments, the share of online purchases in non-recurring payments was highest for the two lowest income groups, and relatively similar for households in income groups with monthly income above €1,000.

Chart 4

Share of online payments in consumers’ non-recurring transactions in terms of number and value of transactions, 2019-2022, by population group

(percentages)

Number of payments

Value of payments

Sources: ECB, calculations based on De Nederlandsche Bank and the Dutch Payments Association (2022) and Deutsche Bundesbank (2022).

3.2 POS transactions

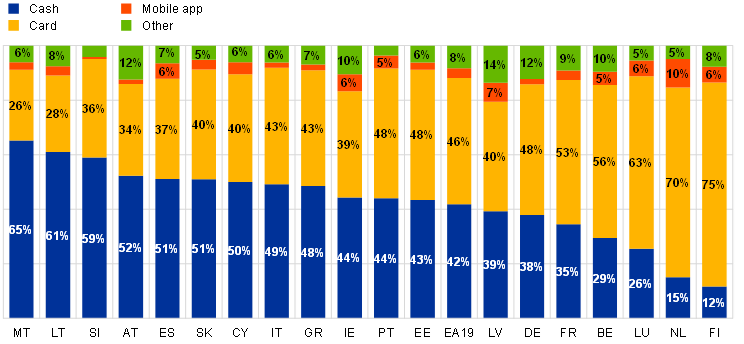

3.2.1 Cross-country differences in payment behaviour at the POS

There are large cross-country differences in the payment habits of consumers when purchasing goods or services at the POS (Chart 5). In several countries, a clear majority of POS payments in 2022 were made in cash. The highest shares in terms of number of payments were observed in Malta (77%), Slovenia (73%), Austria (70%) and Italy (69%), and in terms of value of payments in Malta (65%), Lithuania (61%) and Slovenia (59%). Card payments were the most frequently used method at the POS in 2022 in four euro area countries: Finland (70%), the Netherlands (67%), Luxembourg (52%) and Belgium (48%). In Estonia, the share of card payments was almost identical to the share of cash payments (both 46%).

Although payments with mobile apps have increased in recent years, their share in POS payments was still relatively low. The share of mobile payments (by number of transactions) was highest in the Netherlands (10%), and exceeded 5% in Finland, Ireland, Latvia and Luxembourg.

Chart 5

Share of payment instruments used at the POS in terms of the number and value of transactions, 2022, by country

(percentages)

Number of transactions

Value of transactions

Sources: ECB, calculations based on De Nederlandsche Bank and the Dutch Payments Association (2022) and Deutsche Bundesbank (2022).

Notes: EA19 refers to the euro area (19 countries). The category “Other” includes bank cheques, credit transfers, loyalty points, vouchers and gift cards and other payment instruments. The definition of POS payments differs from the one used in Deutsche Bundesbank (2022), where only payments in supermarkets, local shops, drugstores and petrol stations are included.

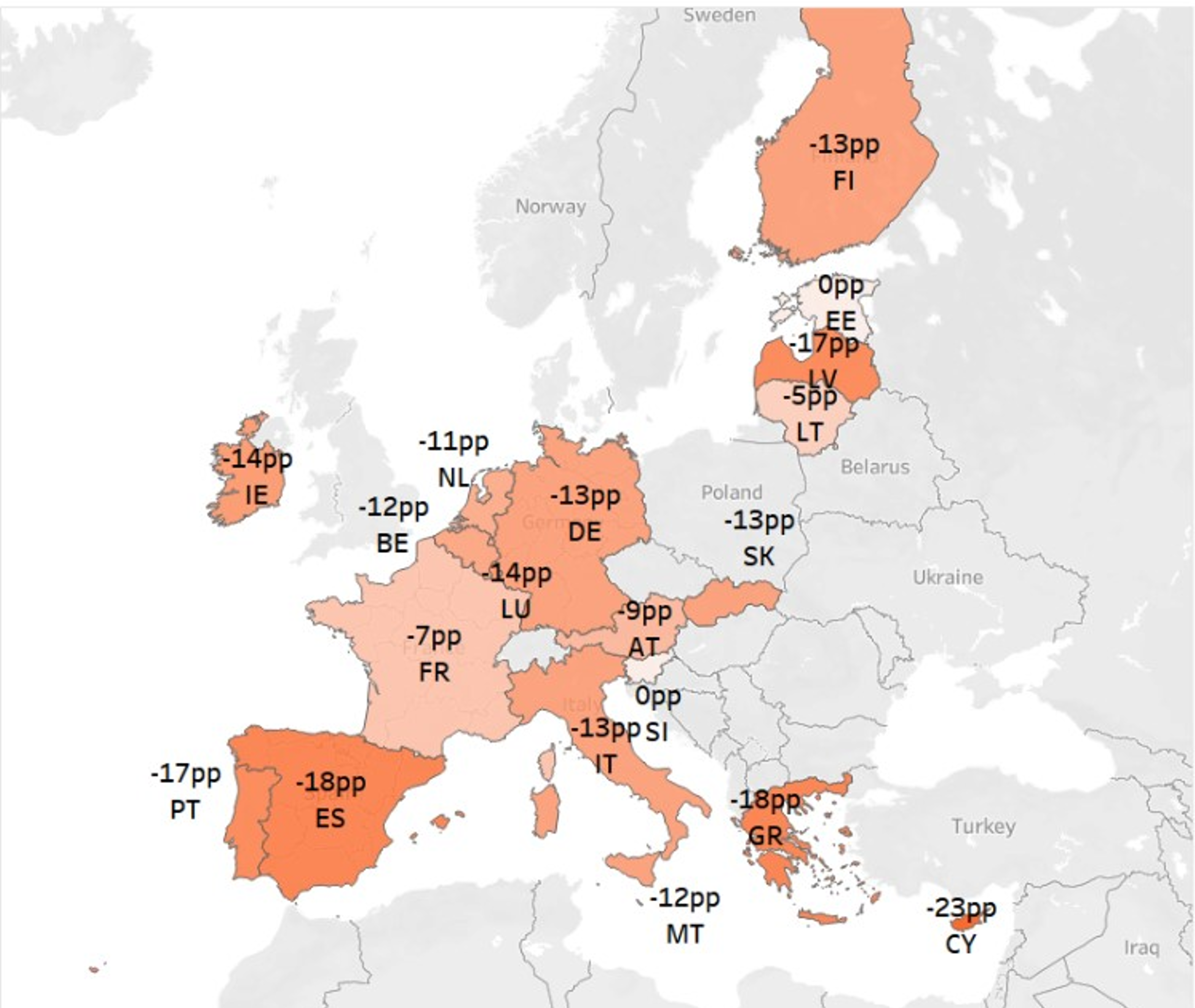

Compared with 2019, the use of cash has declined. This was observed across most euro area countries, although in both Slovenia and Estonia the share of cash payments is virtually unchanged. Cash use declined most in southern European countries: Greece, Spain, Cyprus and Portugal (Figure 1). Measured by value, the share of cash payments has even increased in some euro area countries.

The indicators on payments by value reflect uncertainties, as well as the data for countries that have a small sample size. In particular, variations between the different years and among countries in such cases should be interpreted with caution.[17]

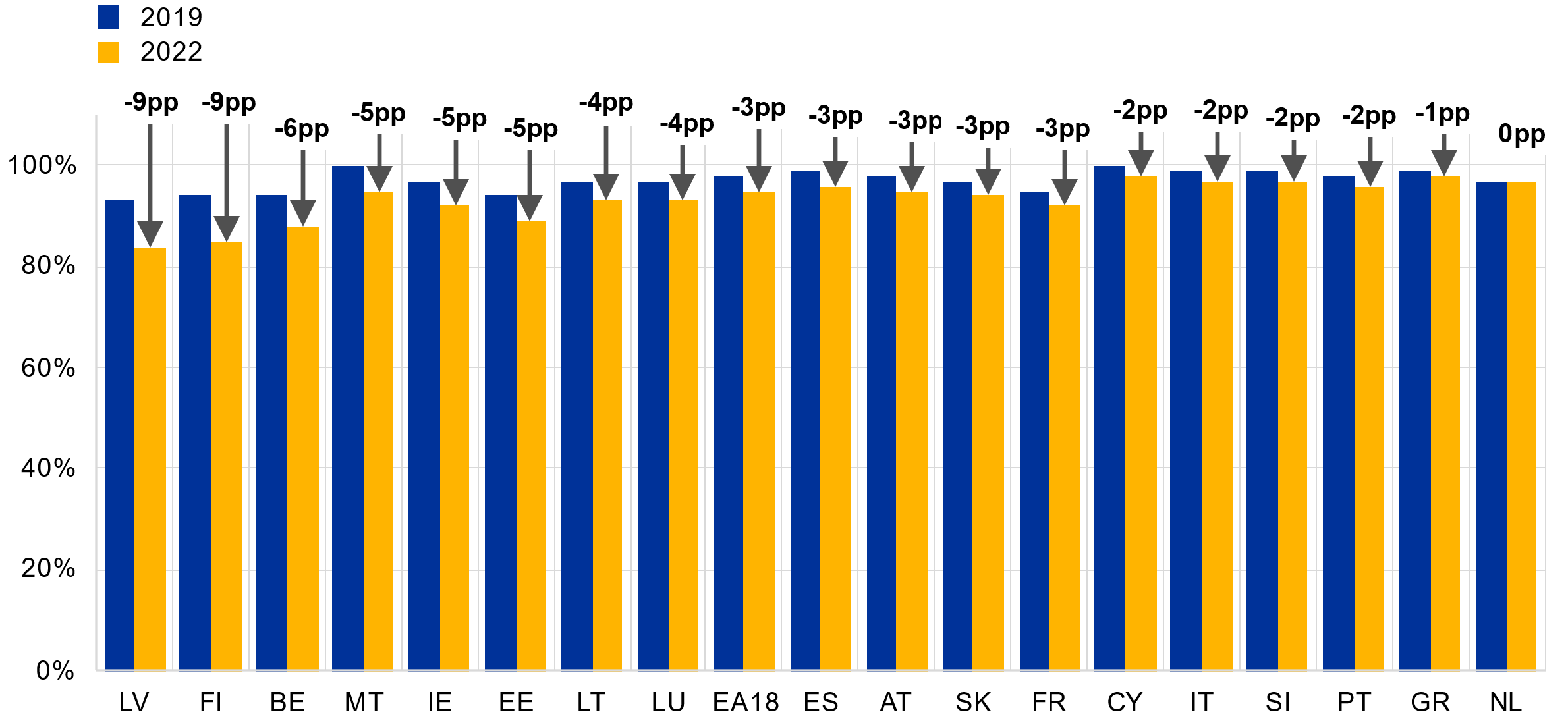

Figure 1

Change in the share of cash transactions at the POS in terms of number and value of transactions in percentage points (pp), 2019-2022, by country

Number of transactions

Value of transactions

Sources: ECB, calculations based on De Nederlandsche Bank and the Dutch Payments Association (2020, 2022) and Deutsche Bundesbank (2018, 2022).

Notes: EA19 refers to the euro area (19 countries). The definition of POS payments differs from the one used in Deutsche Bundesbank (2022), where only payments in supermarkets, local shops, drugstores and petrol stations are included.

3.2.2 Differences in payment behaviour at the POS by subgroup

Looking at the share of cash transactions at the POS by age group, it can be seen that older age groups (i.e. those over 55) tended to use cash relatively more often than younger generations (Chart 6). The share of cash payments in the oldest age group was 5 percentage points higher than the average for all consumers; among those aged 25-39 (who make the least cash payments) it was 4 percentage points lower than the euro area average.

Overall for the euro area, all age groups made more than half of their POS payments in cash. The differences among age groups are similar in terms of value of transactions. All age groups made more payments with cards than with cash in terms of value.

The share of cash payments also declines as respondents’ level of education and income rises.[18] Those with a low level of education reported a share of cash transactions 8 percentage points higher than individuals with a high level of education.[19] The highest earning group paid just above half of its POS transactions with cash, while the lowest income group paid two-thirds. In terms of value, the two highest income groups paid more than 50% of their POS payments with cards.

Chart 6

Share of different payment instruments used at the POS by selected population groups in terms of number and value of transactions, 2022

(percentages)

Number of transactions

Value of transactions

Sources: ECB, calculations based on De Nederlandsche Bank and the Dutch Payments Association (2022) and Deutsche Bundesbank (2022).

Note: The definition of POS payments differs from the one used in Deutsche Bundesbank (2022), where only payments in supermarkets, local shops, drugstores and petrol stations are included.

Box 2

Use of contactless technology for card payments

Contactless technology refers to the ability to pay with cards or electronic devices by holding the card or device a few centimetres away from a retailer’s payment terminal. This technology has made card payments faster and easier in certain settings. These two benefits ranked second and third among the perceived advantages of card payments in 2022 (see Section 6.3). When paying by card using the contactless function it is necessary to switch to chip and personal identification number (PIN) if certain thresholds are exceeded. The most basic transaction value limit was increased to the legally permissible level of €50 per transaction in all euro area countries in 2019.[20] The PIN can also be required after a certain number of transactions per day or when a total amount has been reached, making contactless payments more robust against fraud.

The pandemic accelerated use of contactless payments. For hygiene reasons, the ability to settle a transaction without the need to exchange cash or physically touch the payment terminal made contactless payments more attractive.

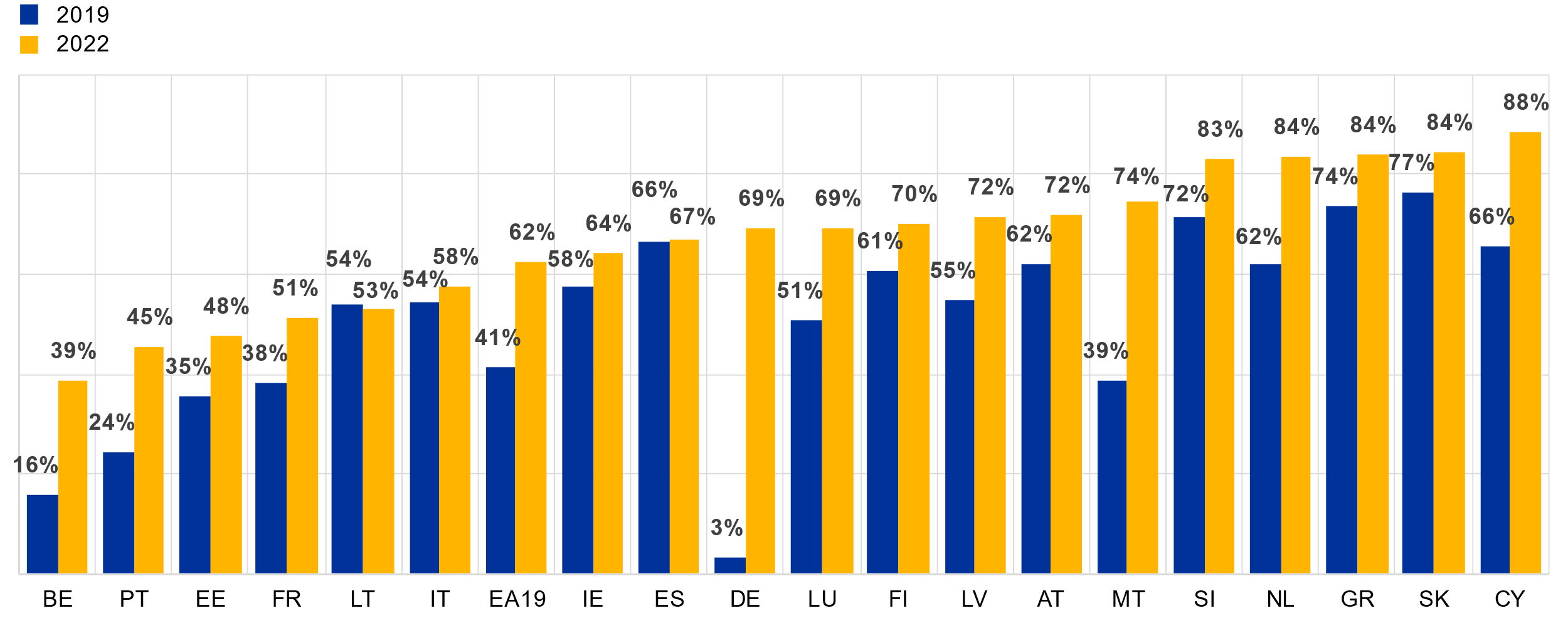

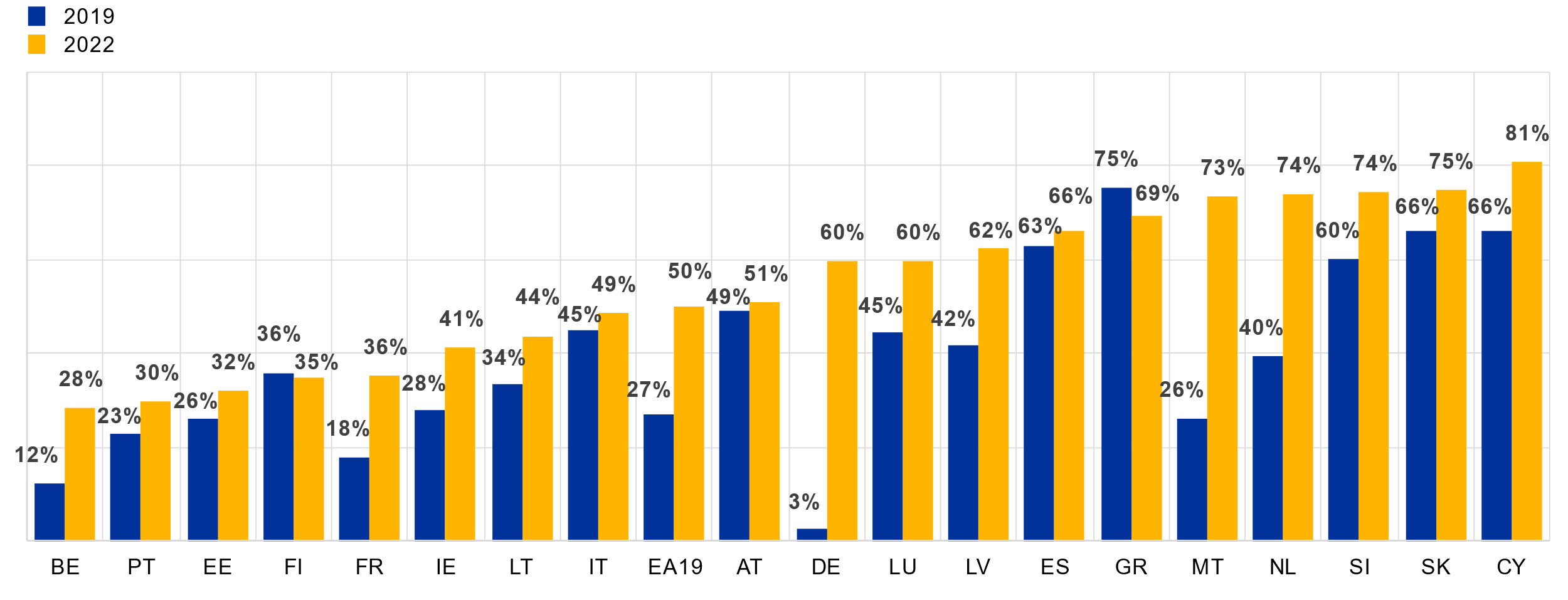

Contactless card payments at the POS went from representing 41% of all card payments in 2019 to 62% in 2022, as shown in Chart A. The change in habits varies substantially between different euro area countries. Lithuania was the only country where contactless payments as a share of the total number of transactions with cards decreased, from 54% to 53%; however, this needs to be interpreted with caution due to possible margin errors. Cyprus was the country where contactless payments had the highest share of total card payments in 2022 (88%), followed by Slovakia (84%) and Greece (84%). Belgium was the country with the lowest share of contactless card payments in 2022 (39%), as it had been in 2019. Germany in particular saw considerable growth in contactless payments as a share of total card payments, although it should be noted that the first data point for Germany is from 2017 rather than 2019.[21]

When it comes to the value of transactions made with contactless payments compared to the total value of transactions made with cards, the share of contactless payments increased from 27% to 50%. Greece and Finland were the only countries that saw the share in the value of contactless transactions decline, falling from 75% to 69% and 36% to 35%, respectively. The three countries with the highest percentage of contactless card payments by value in 2022 were Cyprus (81%), Slovakia (75%) and Slovenia (74%); Belgium had the lowest figure (28%).

Chart A

Share of contactless payments in all card payments at the POS in terms of number and value of transactions, by country

(percentages)

Number of transactions

Value of transactions

Sources: ECB, calculations based on De Nederlandsche Bank and the Dutch Payments Association (2020, 2022) and Deutsche Bundesbank (2018, 2022).

3.3 P2P payments

P2P payments are private payments between individuals not connected to the purchase of goods and services. Examples may include giving pocket money to children or donating money to charity. The breakdown of P2P payments by instrument is quite different from that of POS payments. As can be expected, the role of cards in P2P payments is small, given that private individuals rarely have ability to accept card payments. On the other hand, cash and mobile payments are used for P2P payments more frequently than for POS payments (Chart 7).

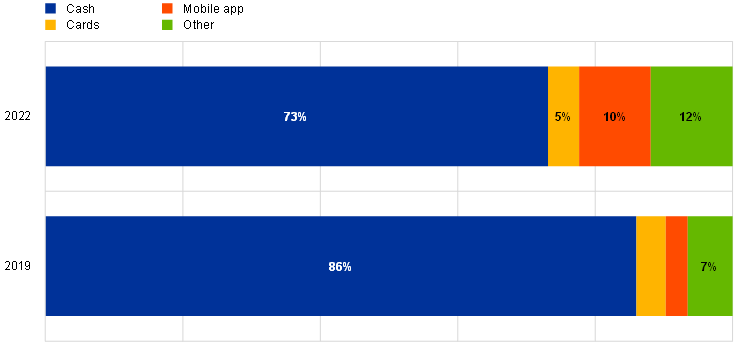

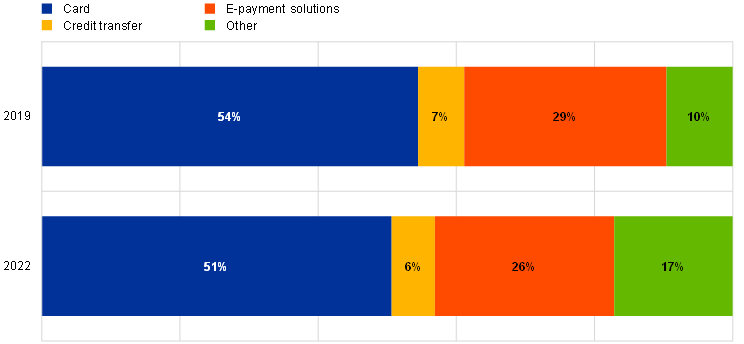

Cash was the dominant means of payment in P2P transactions, although its share in the total number of payments in the euro area declined from 86% in 2019 to 73% in 2022, as shown in Chart 7. In terms of value, the share of cash declined from 65% to 59%. P2P payments with mobile phone apps are becoming more frequent. In 2022,10% of P2P payments were made using mobile phones, compared to 3% in 2019. The share of payment methods other than cash, cards or mobile payments also increased between 2019 and 2022, mainly due to the increase in private payments using credit transfers.

Chart 7

Breakdown of number and value of P2P payments by payment instrument, 2019-2022, euro area

(percentages)

Number of transactions

Value of transactions

Value of transactions

Sources: ECB, calculations based on De Nederlandsche Bank and the Dutch Payments Association (2020, 2022) and Deutsche Bundesbank (2018, 2022).

Note: “Other” includes bank cheques, credit transfers, loyalty points, vouchers and gift cards and other payment instruments.

Looking at P2P payments by country in Chart 8, the share of cash in terms of the number of payments was over 80% in Germany, Cyprus, Slovenia, Greece, Italy and Austria, while cash was used for less than half of P2P transactions in Estonia, Finland and the Netherlands. The share of mobile phone apps in P2P payments was highest in the Netherlands (43%). In Finland, Estonia, Luxembourg and Malta the share of mobile payments in P2P transactions was about 25%. In value terms, the share of mobile payments was even higher, reaching 52% in the Netherlands and 34% in Luxembourg. The role of credit transfers, included in Chart 8 under Other, was also bigger in P2P payments than in payments at the POS.

Chart 8

Share of payment instruments used for P2P payments in terms of number and value of transactions, 2022, by country

(percentages)

Number of transactions

Value of transactions

Sources: ECB, calculations based on De Nederlandsche Bank and the Dutch Payments Association (2022) and Deutsche Bundesbank (2022).

Notes: EA19 refers to the euro area (19 countries). “Other” includes bank cheques, credit transfers, loyalty points, vouchers and gift cards and other payment instruments.

3.4 Online payments

Online payments, as defined in this report, include any payments made online, excluding regular bill payments such as electricity bills or rent. These are analysed separately as recurring payments in Section 5. The SPACE 2022 diary clearly distinguished between online payments and online purchases, meaning that any orders made online but paid at the point of sale (e.g. when picking up food from a restaurant or paying a courier at the door) were reported as POS payments.[22]

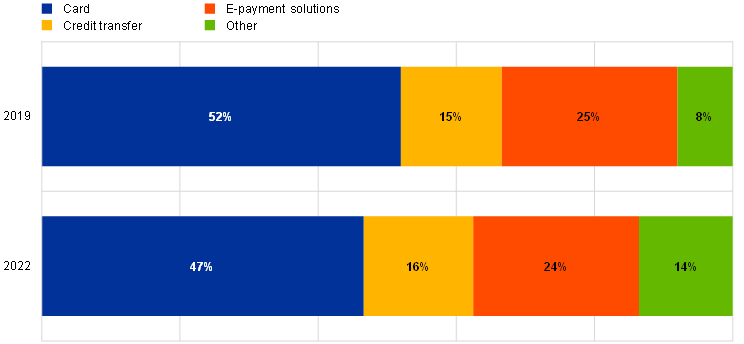

Chart 3 shows that the share of the number of online payments in non-recurring payments increased significantly between 2019 and 2022. In 2022 consumers made over three times more online payments than in 2019. The breakdown of online payments, however, remained relatively stable.

More than half of online payments were made with cards (Chart 9). The share of card payments declined slightly between 2019 and 2022, from 54% down to 51%. The use of PayPal and similar online or mobile payment solutions has decreased slightly. The variety of online payment methods has grown in recent years; 9% of all online payments were made using a method the respondent could not identify from the answer options in the questionnaire.[23]

In terms of payment value, the share of credit transfers was larger. Consequently, credit transfers were used more often for large-value payments compared to other payment instruments.

Chart 9

Breakdown of number and value of online payments by payment instrument, 2019-2022, euro area

(percentages)

Number of payments

Value of payments

Sources: ECB, calculations based on De Nederlandsche Bank and the Dutch Payments Association (2020, 2022) and Deutsche Bundesbank (2018, 2022).

Notes: “E-payment solutions” includes PayPal and other online or mobile payment methods (e.g. Klarna, Sofort, iDeal, Afterpay). “Other” includes loyalty points, vouchers and gift cards, crypto assets and other payment instruments.

The breakdown of online payments varies a great deal by country (Chart 10). The use of e-payment solutions such as iDeal, PayPal and Klarna is by far the most frequent way to pay for online purchases in the Netherlands. E-payment solutions account for a large share of all online payment methods in Germany, too.[24] However, card payments were still the most frequently used instrument for online payments in most euro area countries.

Chart 10

Share of payment instruments used for online payments in terms of number and value of payments, 2022, by country

(percentages)

Number of payments

Value of payments

Sources: ECB (2022), calculations based on De Nederlandsche Bank and the Dutch Payments Association (2022) and Deutsche Bundesbank (2022).

Notes: EA19 refers to the euro area (19 countries). “E-payment solutions” includes PayPal and other online or mobile payment methods (e.g. Klarna, Sofort, iDeal, Afterpay). “Other” includes loyalty points, vouchers and gift cards, crypto assets and other payment instruments. In the 2019 data iDeal was classified under credit transfers.

4 Payment behaviour by value range and purpose

4.1 POS and online payments by value range

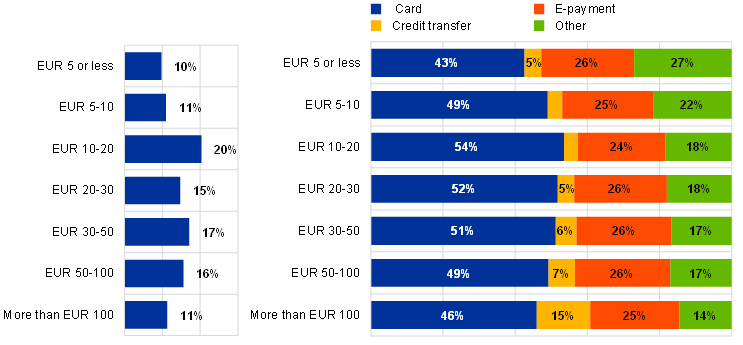

Purchase price influences how and where consumers pay for goods and services. Smaller-value purchases are typically paid for at the POS, with higher-value payments more often made online. In 2022, the share of POS payments under €20 was almost 60%, while only 4% of POS payments had a price higher than €100. Conversely, online purchases for less than €10 were infrequent and more than one online payment in four had a price over €50 (see Chart 11, left-hand panel).

Chart 11

Breakdown of POS and online payments by value range and payment instrument, 2022, euro area

(percentages)

POS transactions

Online payments

Sources: ECB, calculations based on De Nederlandsche Bank and the Dutch Payments Association (2022) and Deutsche Bundesbank (2022).

Note: For POS payments, “Other” includes bank cheques, credit transfers, loyalty points, vouchers and gift cards and other payment instruments. For online payments, “E-payment solutions” includes PayPal and other online or mobile payment method (e.g. Klarna, Sofort, iDeal, Afterpay). “Other” includes, loyalty points, vouchers and gift cards, crypto assets and other payment instruments.

The share of various payment instruments used for high and low-value payments is very different. Looking at POS transactions, the use of cash was especially common for purchases of lower value, in line with the findings of previous surveys. Four out of five POS purchases for less than €5 were paid with cash (Chart 11). Although mostly in line with previous surveys, the share of card transactions for low-value payments has increased since 2019. For example, for payments below €5, the share of payments using a card went from 7% in 2019 to 15% in 2022. Similarly, for payments between €5 and €10, the share of card payments went from 15% in 2019 to 24% in 2022.

The share of cash transactions declines significantly with transaction value. For purchases over €50, cards were the most frequently used payment method at the POS. However, almost one-third of POS payments over €100 were still made with cash. The share of payments with a mobile app was relatively stable across value ranges, although they were used slightly more frequently for higher-value payments.

There is no clear pattern in the use of online payment methods for purchases of different value. Credit transfers were used more frequently for higher-value payments and cards slightly less frequently. PayPal and other e-payment solutions were used for about one online payment in four, regardless of their value.

4.2 POS and online payments by location and purpose

4.2.1 Payments at the POS by location

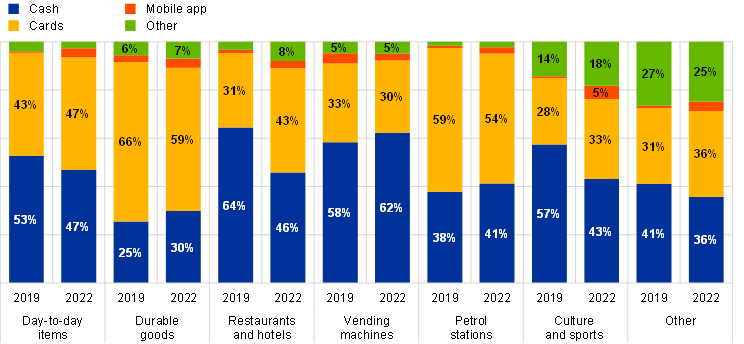

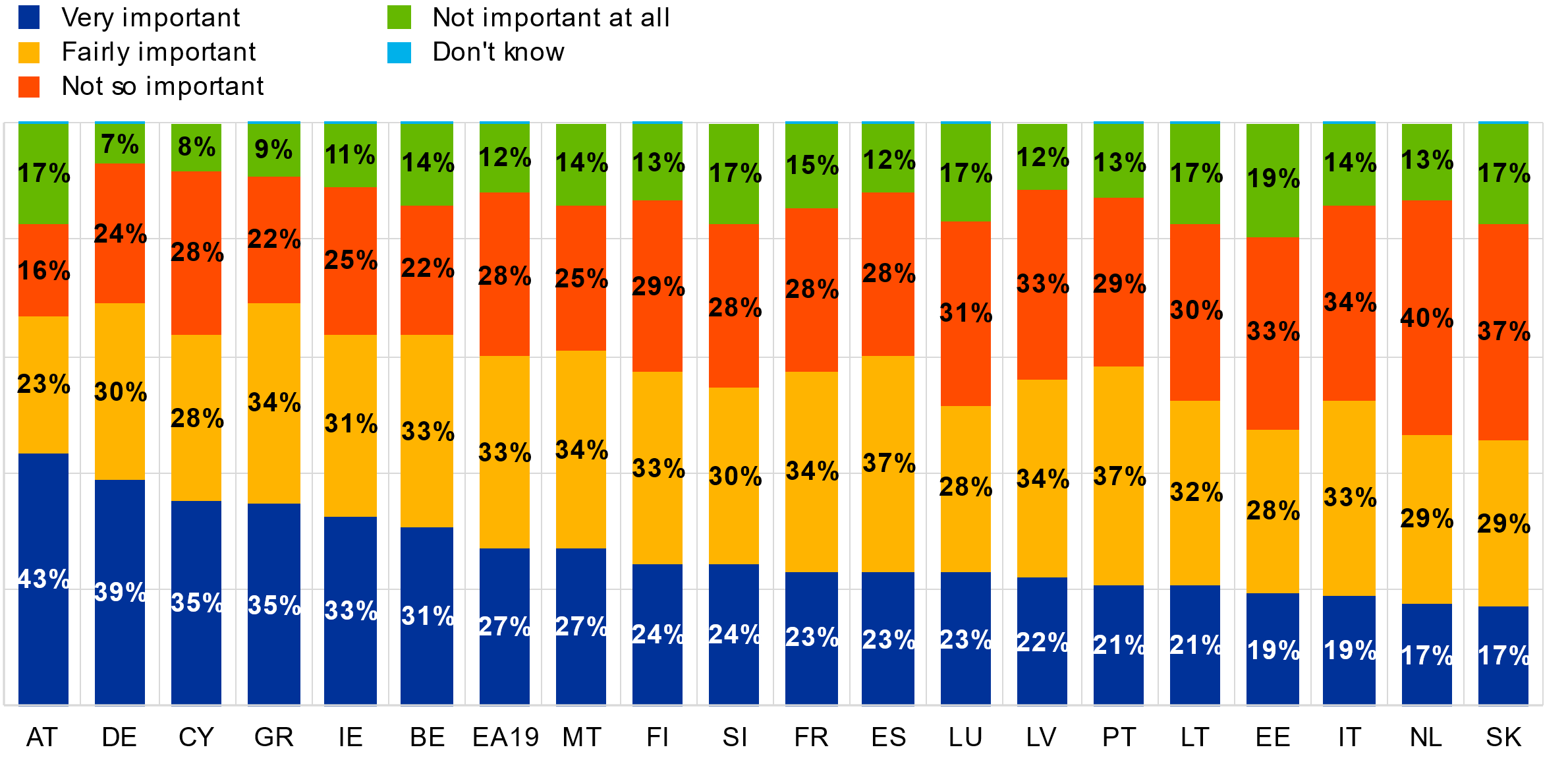

Payments at the point of sale include very different kinds of purchases. Consumers can for example buy day-to-day goods at a supermarket, consumer durables or home services, make purchases in hotels, restaurants, venues for culture and sports or petrol stations, or buy tickets or other goods from vending machines. SPACE 2022 aimed to capture different payment situations as accurately as possible in order to understand how consumers’ payment behaviour differs across a variety of locations and purposes (see Chart 12).

Most transactions, both in terms of number and value, were made in supermarkets and other shops selling day-to-day goods. Their share of the total number of purchases was 54% in 2022. The share of restaurants, cafes and hotels was 18%.

The breakdown of payments by location remained essentially stable from SPACE 2019. In 2022 consumers were making slightly more transactions in supermarkets and other shops selling day-to-day goods. Payments at restaurants, cafes and hotels declined slightly; this may reflect patterns learnt during the pandemic. While food stores were kept open during most lockdown periods, restaurants and hotels stayed closed for extended periods in some euro area countries. The share of payments at venues for sports, culture and entertainment also declined, but this figure was already relatively low in 2019. Although there were no significant lockdowns during the fieldwork periods in the autumn of 2021 and spring of 2022, consumption behaviour learnt during the pandemic may still have had a longer-term behavioural impact on consumers. Looking at the value of POS transactions, only limited changes in payment behaviour by location were witnessed compared with 2019.

Chart 12

Breakdown of POS payments in terms of number and value, 2019 and 2022, euro area, by location

(percentages)

Number of transactions

Value of transactions

Sources: ECB, calculations based on De Nederlandsche Bank and the Dutch Payments Association (2022) and Deutsche Bundesbank (2022).

Notes: “Day-to-day items” includes purchases from supermarkets, shops for day-to-day items and street markets or vendors. “Restaurants and hotels” includes restaurants, bars and cafes, hotels and similar. “Other” includes services outside, inside or around the home, at public authorities and post offices, and at other physical locations.

Cash was used most frequently for payments at vending machines (74%), in restaurants and hotels (68%) and in supermarkets and other shops selling day-to-day goods (61%). In shops selling durable goods the share of card transactions was higher than the share of cash transactions (51% compared to 39%). Mobile app payments were used with similar frequency across all locations; the share varied between 3% and 5%. The highest share of mobile payments was reported in venues for culture and sports (see Chart 13).

Overall, consumers were using cash less frequently at the POS in 2022 than they did 2019. There are considerable differences in how this change in behaviour was observed in various types of locations. The share of cash transactions declined by more than 10 percentage points in restaurants and hotels, venues for culture and sports, supermarkets and other shops selling day-to-day items, as well as in other places, which includes home services, public offices and other non-categorised venues. On the other hand, cash was used in 2022 at approximately the same frequency for payments at petrol stations and vending machines as in 2019. In fact, the share of cash payments by value at these locations even increased.

Chart 13

Breakdown of POS payments by location and payment instrument, 2019 and 2022, euro area

(percentages)

Number of transactions

Value of transactions

Sources: ECB, calculations based on De Nederlandsche Bank and the Dutch Payments Association (2022) and Deutsche Bundesbank (2022).

Notes: “Day-to-day items” includes purchases from supermarkets, shops for day-to-day items and street markets or vendors. “Restaurants and hotels” includes restaurants, bars and cafes, hotels and similar. “Other” includes services outside, inside or around the home, at public authorities and post offices, and at other physical locations.

4.2.2 Online payments by purpose

SPACE collects data on online payments by purpose, distinguishing between the most frequent purposes of non-recurring payments, such as food and daily supplies, clothes, household durables and media and entertainment (e.g. games and music). Between 2019 and 2022 consumers increased their online shopping considerably, as mentioned earlier. The breakdown of online payments by purpose also changed considerably.

Online shopping for food and daily supplies, including both restaurant and grocery store deliveries, has become much more frequent. Online delivery was the only available means of purchasing restaurant food almost everywhere at the height of lockdown, with evidence suggesting consumers may have retained the habit even after the pandemic. The share of payments for food in all online payments has grown from 10% to 24%, as seen in Chart 14. Buying medicine and cosmetics online has also become more frequent. The share of online payments for all other purposes decreased compared to payments for food and medicine. Given the large increase in total online shopping, this does not necessarily indicate that the total value of online shopping for these purposes (e.g. clothes and consumer durables) has decreased.

Chart 14

Breakdown of online payments by purpose, 2019 and 2022, euro area

(percentages)

Number of payments

Value of payments

Sources: ECB, calculations based on De Nederlandsche Bank and the Dutch Payments Association (2022) and Deutsche Bundesbank (2022).

Notes: Data for 2019 does not include Germany. “Household durables” includes electronic goods, household appliances and furniture. “Other” includes charitable donations, financial products, luxury goods, household services and other purposes.

5 Recurring payments

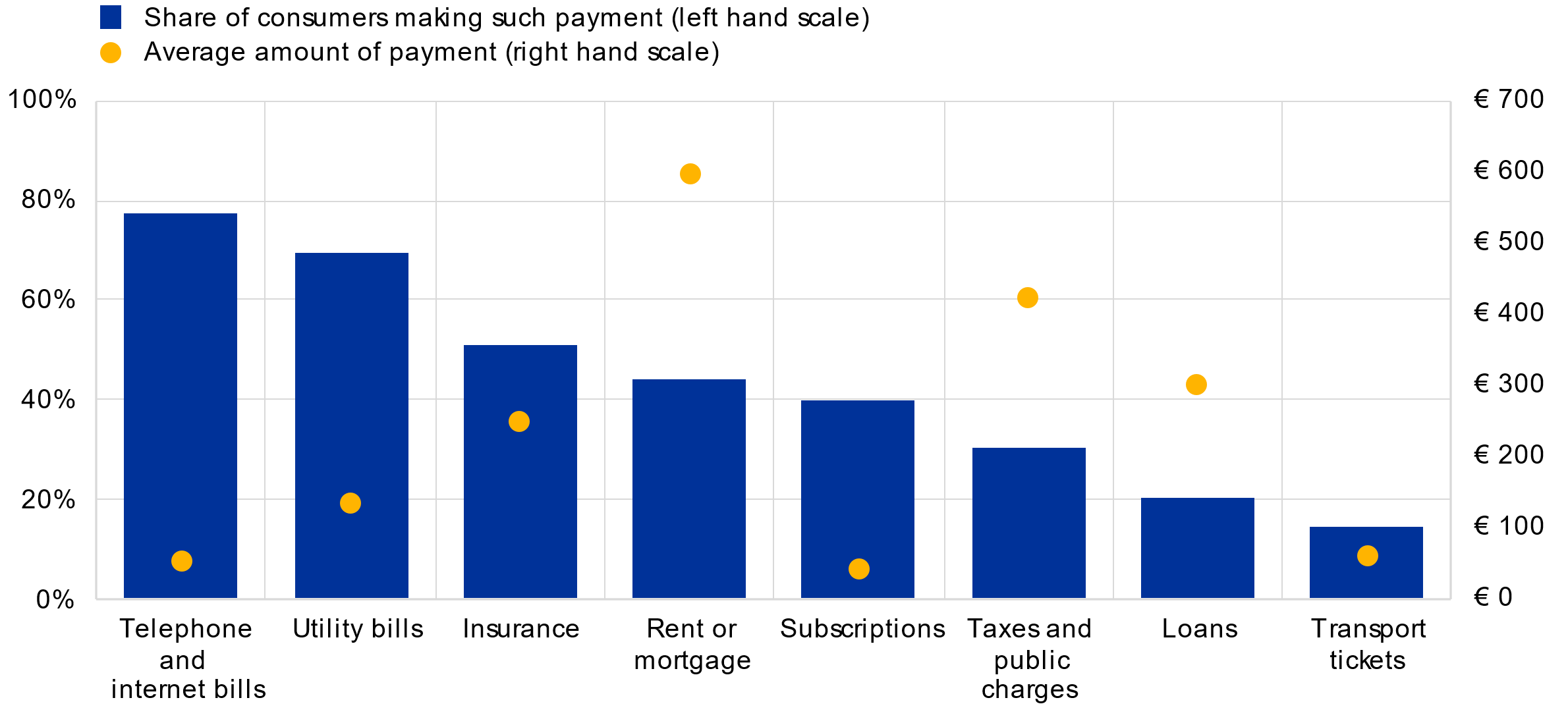

In addition to day-to-day payments, consumers make various kinds of recurring payments on a weekly, monthly, annual or other basis. SPACE 2022 collected information on recurring payments in eight categories: rent or mortgage, utility bills, insurance, telephone or internet bills, taxes and public charges, subscriptions (e.g. magazines, sports club, streaming TV), season tickets for transport and loans. The SPACE data refer to payments made by individuals during the 30-day reporting period.[25]

Recurring payments were most frequently used for telephone and internet bills (78%), followed by utility bills (70%) and insurance (51%), as indicated in Chart 15. About 20% of consumers paid back consumer loans and 14% purchased season tickets for public transport. The average value of payments differs substantially between the various payment types, from €41 for subscriptions to almost €600 for rent or mortgage.

Chart 15

Recurring payments by type: average payment and share of consumers making such payments, 2022, euro area

(percentages)

Sources: ECB, calculations based on De Nederlandsche Bank and the Dutch Payments Association (2022) and Deutsche Bundesbank (2022).

Recurring payments are of a very different nature to daily transactions, and consequently the patterns of using various payment instruments are also different. For most types of recurring payment direct debit was the most frequently used instrument, used by approximately half of consumers. Another 30-40% paid their recurring bills by credit transfer. Cards, cash or other instruments were used by less than 10% of consumers for most recurring payments.

Two categories, subscriptions to magazines, streaming TV, etc. and tickets for public transport follow different patterns (Chart 16). This may be explained by the smaller amounts of such payments, as well as the distinct profile of consumers opting to make such payments and the fact that transport tickets are normally bought at physical locations (e.g. dedicated machines). While direct debit was the most frequently used method for subscriptions, card payments were used most often for transport tickets. For the latter, 24% of recurring payments were made in cash, indicating that they are often made at the POS rather than remotely.

Chart 16

Breakdown of recurring payments by payment instrument in terms of number and value, 2022, euro area

(percentages)

Number of payments

Value of payments

Sources: ECB (2022), calculations based on De Nederlandsche Bank and the Dutch Payments Association (2022) and Deutsche Bundesbank (2022).

Note: “Other” includes bank cheques and other payment instruments.

6 Preferences for and advantages of cash and cashless payments

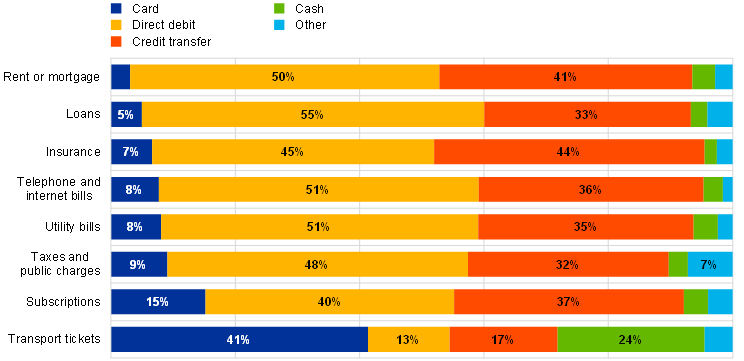

6.1 The importance of having the option to pay with cash

While use of and preferences for cash payments are on a declining trend, the importance of cash remains at a high level.[26] Overall, 60% of the euro area population considered having the option to pay with cash to be very or fairly important, as it can be seen in Chart 17. More than half of the population considered the option to pay with cash fairly or very important in this survey, even in countries like Belgium, Luxembourg and Finland, where consumers were using other payment options for the majority of POS purchases.

Chart 17

The importance of having the option to pay with cash, by country

(percentages)

Sources: ECB (2022), De Nederlandsche Bank and the Dutch Payments Association (2022) and Deutsche Bundesbank (2022).

Notes: EA19 refers to the euro area (19 countries). The survey question was: “How important is it for you to have the option of using cash?”

Looking across demographic groups, Chart 18 shows that the ability to always pay in cash seemed to be more important for respondents older than 55 and those with upper/post-secondary education, with no notable differences by gender.

Chart 18

The importance of having the option to pay in cash, by demographic

(percentages)

Sources: ECB (2022), De Nederlandsche Bank and the Dutch Payments Association (2022) and Deutsche Bundesbank (2022).

Notes: The gender category “Other” is not shown as the sample in the survey is not sufficient to draw inferences. The survey question was: “How important is it for you to have the option of using cash?”

6.2 Preferences at the POS

How people pay can be influenced by various factors; revealed preferences may be one of these. Payment preferences play a major role in guiding consumers’ use of different payment methods and are influenced by several factors: age, income, habits, education, job, etc. This section shows the declining preference for cash at the POS as well as the trends for online payments.

The extent to which paying by different means (cash, cards, credit transfer, direct debit, e-money or other means) is preferred differed greatly from country to country (Chart 19). Overall, the general preference for cash decreased by 5 percentage points from SPACE 2019 (Chart 20). Since 2016, strict cash preference has witnessed a steady decline – from 32% of the respondents preferring it in 2016, down to 27% in 2019 and 22% in 2022.

Chart 19

Preferred payment instrument by country

(percentages)

Sources: ECB, calculations based on De Nederlandsche Bank and the Dutch Payments Association (2022) and Deutsche Bundesbank (2022).

Notes: EA19 refers to the euro area (19 countries). The survey question was: “If you were offered various payment methods in a shop, what would be your preference?”

Nonetheless, in a few countries the preference for cash increased from 2019: Belgium (up 9 percentage points), Estonia (up 7 percentage points), France (up 5 percentage points), Austria (up 3 percentage points) and Slovenia (up 2 percentage points).[27] See Chart 20.

Chart 20

Preferences for cash, 2019 vs. 2022

(percentages)

Sources: ECB, calculations based on De Nederlandsche Bank and the Dutch Payments Association (2020, 2022) and Deutsche Bundesbank (2022).

Notes: EA19 refers to the euro area (19 countries). The survey question was: “If you were offered various payment methods in a shop, what would be your preference?”. Bars show those who answered “Cash”.

Despite a declining stated preference for cash, it remained the most used payment instrument for POS transactions, being used in 59% of them (see Chart 2). Once again, this is testament to the discrepancy between consumers’ stated preferences and their actual behaviour, as identified in previous studies such as SPACE 2019. The reasons might be various. The question is asked in general, and no distinction can be made between high-volume payments and low-volume ones. Respondents might have a preference for cash when making low-value payments, for instance. Another reason could be acceptance of different means of payment on the part of the merchant. The literature suggests that higher cash usage is associated with lower levels of perceived card acceptance at the POS (Bagnall et al., 2016; Wakamori and Welte, 2017).

Looking at euro area results by demographics (see Chart 21), no big difference emerged between male and female behaviour. Around 21% of male respondents and 22% of female respondents preferred cash, compared to 55% of male and 54% of female respondents who preferred cashless payment.[28] A more pronounced difference can be seen in the attitude of people in the age groups 18-24 and 65+. In fact, 24% of each of these two categories stated they prefer cash, against 20% of the age groups 25-39 and 40-54. 23% of respondents aged 55-64 expressed a cash preference. In terms of education level, 24% of respondents with a primary or lower-secondary education declared they prefer cash, against 17% of people holding a university-level education or a PhD.

Chart 21

Preferences for cash or cashless payment, by demographic

(percentages)

Sources: ECB, calculations based on De Nederlandsche Bank and the Dutch Payments Association (2022) and Deutsche Bundesbank (2022).

Notes: EA19 refers to the euro area (19 countries). The gender category “Other” is not shown as the sample in the survey is not sufficient to draw inferences. The survey question was: “If you were offered various payment methods in a shop, what would be your preference?”

6.3 Perceived advantages of payment instruments, cash and cards

According to Hernandez et al (2017), how consumers perceive payment instruments, and their characteristics influences payment behaviour. SPACE 2022 collected information on the perceived main advantages of cash and cards. The main reasons why cash is preferred were: (i) cash is considered to make one more aware of one’s own expenses; (ii) cash is perceived as anonymous (and therefore protects privacy); (iii) cash transactions are perceived to be immediately settled. The first two reasons were chosen by 40% of the population (see Chart 22).

Chart 22

Reasons for preferring cash

(percentages)

Top three advantages of cash

Sources: ECB, De Nederlandsche Bank and the Dutch Payments Association (2022) and Deutsche Bundesbank (2022).

Notes: Percentages do not add up to 100%, as respondents could choose up to three answers each. The survey question was: “For you personally, what are the three most important advantages of cash as compared with card payments? Cash payments…”

Two of the three most important perceived advantages of cash have changed dramatically over the past five years.[29] In 2016, 42% of the population stated that by using cash they had a clear overview of their own spending. However, when it came to the second and third advantages, 38% answered that cash was always accepted (against the 27% in 2022 who said it was accepted in more situations), while 32% stated that cash payments were fast (against 19% in 2022). Not only has the preference for the wide acceptance of cash declined – anonymity has acquired a more prominent role in respondents’ opinions, rising from 13% in 2016 to over 40% in 2022. This could be partly for methodological reasons, as anonymity and privacy protection were bundled together in 2022, while the 2019 survey only asked respondents about their preference for anonymity. However, since not all respondents may appreciate the difference between anonymity and privacy protection, it is possible that awareness of privacy protection has increased. The fact that cash payments are immediately settled has acquired importance; in 2016 only 13% selected that option as an advantage. The ease and safety of cash payments, on the other hand, have stayed relatively constant (ease: 21% in 2016, 19% in 2022; safety: 16% in 2016, 17% in 2022).

When it comes to the advantages of card payments, a relatively large majority (62%) saw the key advantage as being that they don’t have to carry a lot of cash with them (see Chart 23). In 2016 only 33% cited a similar, although not identical, reason (avoiding the need to check whether you are carrying enough cash). Other reasons selected for preferring cards to cash have hardly changed. The share of the population deeming card payments easier has decreased slightly (down from 40% to 37%), while the share of those thinking card transactions are faster has grown 5 percentage points (up from 35% to 40% of respondents). Consumers feeling that card transactions are safer have increased 3 percentage points (23% to 26%). Almost no change is visible in consumers who see widespread acceptance as a top advantage (20% in 2016; 19% in 2022).

Chart 23

Reasons for preferring cards

(percentages)

Top three advantages of cards

Sources: ECB, De Nederlandsche Bank and the Dutch Payments Association (2022) and Deutsche Bundesbank (2022).

Notes: Percentages do not add up to 100%, as respondents could choose up to three answers each. The survey question was “For you personally, what are the three most important advantages of card payments compared with cash? Card payments…”

7 Cash in wallet and cash reserves

This section presents an analysis of both cash reserves and cash in wallet maintained by euro area citizens.

The likelihood of using cash for transactions increases when the level of cash holdings is higher (Bagnall et al., 2016; Arango et al., 2015). Estimating the amount of cash in wallet might shed light on the reasons behind consumers’ decision to pay in cash. Respondents in the survey were asked to report the exact amount of cash in their wallet at the beginning of the day. People in the euro area possessed an average of €83 in their wallet, as shown in Chart 24. The average amount of cash held varied across countries. In Austria, Luxembourg, Cyprus and Lithuania the average amount was more than €110 – not too divergent from the 2019 findings.

Chart 24

Average amount of cash in wallet at the beginning of the day, by country

(percentages)

Sources: ECB, De Nederlandsche Bank and the Dutch Payments Association (2022) and Deutsche Bundesbank (2022).

Note: The chart shows the average excluding respondents declaring they had more than EUR 5,000 in their pockets at the beginning of the day.

As already seen in SPACE 2019, cash is also used as a store of value in the euro area (European Central Bank, 2020). Indeed, estimates from 2019 suggest that as much as around 28-50% of the value of euro banknotes in circulation is used to store value in the euro area (Zamora-Pérez, 2021). The new survey data from 2022 indicate that people are keeping more cash reserves now than before (37% of euro area consumers in 2022, compared with 34% in 2019), as depicted in Chart 25. It could be that this was because of the pandemic and uncertainty in the economy, and a perceived need to keep cash on hand at home because it is portable, fungible, and immediately useful offline. Cash might also be habitual for some groups, and cash management is a useful way to keep track of a fixed budget (Financial Conduct Authority, 2021). In the euro area, Slovakia (58%) and Estonia (49%) ranked among the highest in the share of population reporting they keep extra cash on hand as a store of value. France (30%) and Cyprus (25%) ranked lowest. Cyprus also saw the highest share of the population refusing to answer whether they keep extra cash holdings – almost 10%. This shows that cash management can be a deeply personal issue for many people, and is in line with the 40% of people who like the anonymity cash affords them.

Chart 25

Share of consumers keeping extra cash reserves

(percentages)

Sources: ECB, De Nederlandsche Bank and the Dutch Payments Association (2022) and Deutsche Bundesbank (2022).

Note: The survey question was: “Do you personally keep extra cash that is not in your wallet, purse or pocket?”

Cash received as part of income could influence cash usage in transactions. The results show that most euro area citizens (85%) did not receive any regular income in cash (see Chart 26). This figure was marginally higher in 2019, at 87%. Greece was an outlier, in that 11% of people in that country received up to a quarter of their income in cash (roughly twice the euro area average of 5%); 8% received half and 9% received more than three-quarters. This indicates a stronger cash dependency in Greece than other Member States, at least in terms of willingness to accept cash as opposed to other options like direct deposit.

Chart 26

Share of regular income received in cash

(percentages)

Sources: ECB, De Nederlandsche Bank and the Dutch Payments Association (2022) and Deutsche Bundesbank (2022).

Note: The survey question was: “How much of your regular income (e.g. wages, pensions or allowances) do you receive in cash?”

8 Consumer access to and acceptance of means of payment

Ensuring equitable access to cash is a fundamental part of the Eurosystem’s Cash 2030 Strategy. The overall number of ATMs per inhabitant has increased slightly, but only partly offset the continued closure of bank branches (Zamora-Pérez, 2022). However, in some euro area countries – most notably Belgium and the Netherlands – the ATM network has actually shrunk (Zamora-Pérez, 2022) leading to concerns about the ability of more vulnerable people to make payments. The Eurosystem also looks into how access for all citizens can be promoted in the payments sector, as part of its retail payments strategy.[30] With the payment mix undergoing continued changes, it is the role of the Eurosystem to ensure that people continue to have the freedom to pay wherever they want, irrespective of geographical location. Access to a given means of payment can be an important factor in determining how people decide to pay. Anticipating trends in changing payment behaviour and the logistical requirements needed to continue to provide cash is a way of upholding people’s universal right to public money should they choose to use it. Cash can be obtained from various sources: withdrawals in bank branches, from ATMs and from retailers via cashback services or cash-in-shop.

8.1 Access to cash

Access to cash withdrawals is a key way of measuring how much freedom of choice consumers ultimately have when making a payment. The ease with which it can be accessed may influence consumers’ propensity to choose cash when deciding what option to use from the range of payment methods available. When asked about their views on ease of access to cash withdrawals (Chart 27), half (50%) of the population polled said access to cash withdrawals was very easy, which is roughly similar to the results in 2019. Another 39% scored it as fairly easy while only 7% said it was fairly difficult and 3% found it very difficult.

Chart 27

Ease of access to cash withdrawals in the euro area

(percentages)

Sources: ECB, De Nederlandsche Bank and the Dutch Payments Association (2022) and Deutsche Bundesbank (2022).

Note: The survey question was: “When you need to withdraw cash, how easy or difficult do you usually find it to get to an ATM or a bank?”

Specifically on cash withdrawals (Chart 28), there was a worsening trend in the difficulty of obtaining cash from ATMs in some countries, especially Belgium (up 12 percentage points) and the Netherlands and Luxembourg (each up 7 percentage points). However, most countries across the euro area have seen a perceived increase in ease of access to cash withdrawals. Lithuania (minus 3 percentage points) and Estonia (minus 4 percentage points) both witnessed reductions in the difficulty of accessing an ATM, as did Slovenia (also minus 4 percentage points). Other countries to see modest gains include Greece (minus 1 percentage point); the most substantial improvement in ease of access to cash from ATMs was in Malta (minus 6 percentage points). In four countries (Ireland, France, Italy and Latvia), perceived ease of access remained stable.

The European Commission (2022) noted that 46% of all EU citizens find it very easy to withdraw cash at ATMs or a physical bank branch in the area where they live, and 40% find it rather easy.[31]

Chart 28

Share of respondents perceiving access to cash withdrawals to be fairly or very difficult, by country

(percentages)

Sources: ECB, De Nederlandsche Bank and the Dutch Payments Association (2022) and Deutsche Bundesbank (2022).

Note: The survey question was: “When you need to withdraw cash, how easy or difficult do you usually find it to get to an ATM or a bank?”

As already mentioned, the Eurosystem is committed to ensuring that people and businesses have access to their money – whatever their preferences and payment needs.

Cash can be accessed from various sources: bank branches, an ATM, or cashback and cash-in-shop services provided by retailers.[32] The preferred source of withdrawal remained ATMs, while Germany (30%) and Malta (25%) boasted the highest share of respondents citing cash reserves as a third-order preference, as shown in Chart 29.[33]

Chart 29

Sources of cash withdrawals, by frequency of use and country

(percentages)

Sources: ECB, De Nederlandsche Bank and the Dutch Payments Association (2022) and Deutsche Bundesbank (2022).

Notes: The Dutch questionnaire included options to answer “From a friend” and “From my employer”. In SPACE these options figured in a separate question: “What was the amount of cash you received from someone (e.g. as salary, gift, refund, repayment)?” and are not included in this chart.

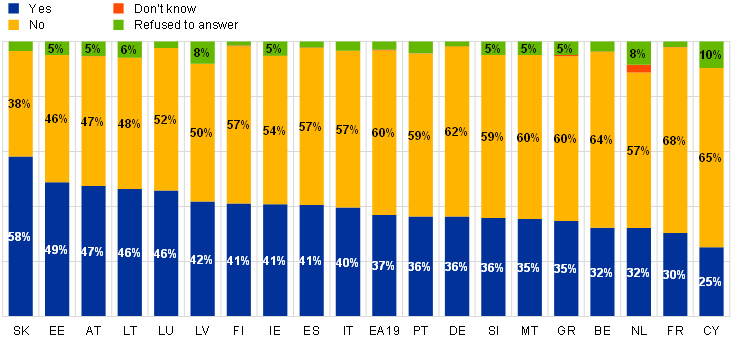

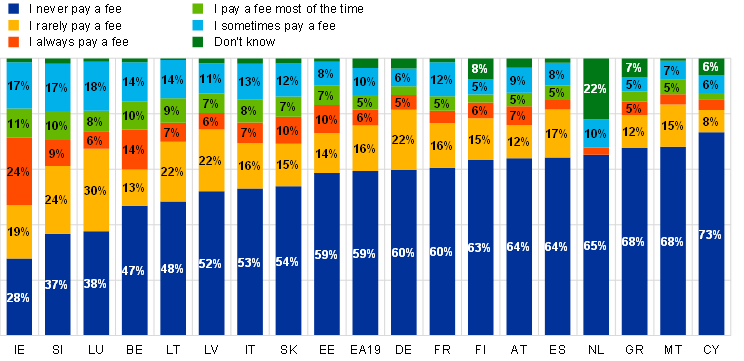

Fees and the number of withdrawals permitted vary across countries. As with ease of access, this may influence consumer withdrawal patterns and, in the absence of an alternative source of cash, exacerbate problems related to access. Chart 30 shows the frequency at which consumers reported having to pay fees, highlighting the different fee structures across countries. In most countries, more than half of consumers report not having to pay a fee at all. Exceptions to this include Ireland, where 24% of consumers said they always pay a fee when withdrawing, and Belgium (14%) – one of the countries where ease of access to cash has become more difficult since 2019.

Chart 30

Proportion of respondents likely to pay fees for cash withdrawals, by country

(percentages)

Sources: ECB, De Nederlandsche Bank and the Dutch Payments Association (2022) and Deutsche Bundesbank (2022).

Note: The survey question was: “Which of the following applies to your cash withdrawals from a cash dispenser (ATM) when using a debit card?”

8.2 Access to non-cash means of payment

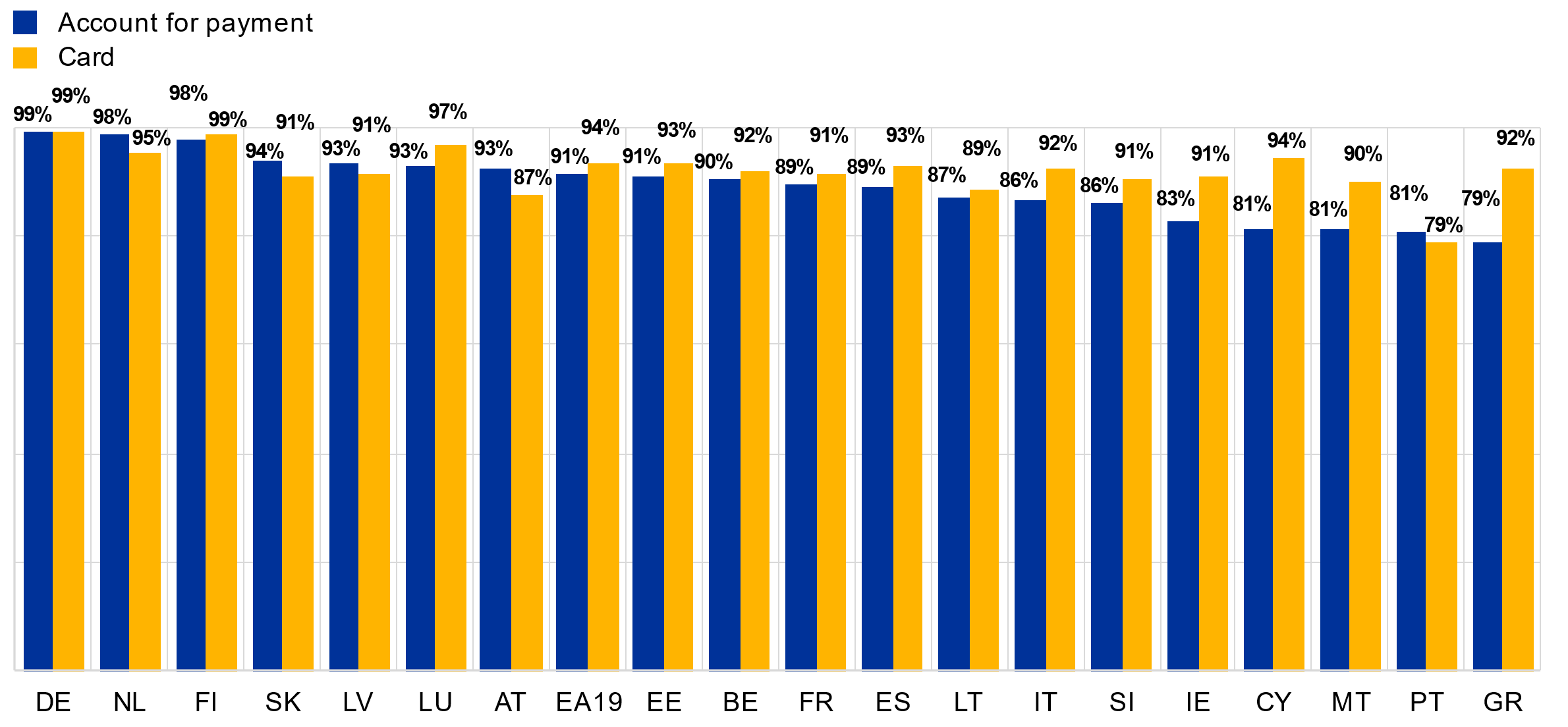

Access to other payment options is of paramount importance for financial inclusion. Consumers cannot make card payments without prior access to a payment card or pay by credit transfer or direct debit if they do not hold payment accounts. Consequently, the survey asked people whether they had access to payment accounts and payment cards. It also touched on evolving trends such as ownership and use of crypto assets, described in Box 3.

Chart 31 shows that, on average, 94% of respondents in the euro area reported having access to a payment card, while 91% reported having an account for payments. The country breakdown shows that the share of consumers that have access to an account for payments was highest in Germany (99%); Greece was lowest at 79%.[34] Germany and Finland reported the highest percentage with access to a payment card (99% each), while Portugal (79%) reported the lowest.

Chart 31

Share of consumers that have access to an account for payments and a card

(percentages)

Sources: ECB, De Nederlandsche Bank and the Dutch Payments Association (2022) and Deutsche Bundesbank (2022).

Note: The survey question was: “Which of the following do you have? 1. An account from which you can make payments; 2. Card (debit card or credit card)”.

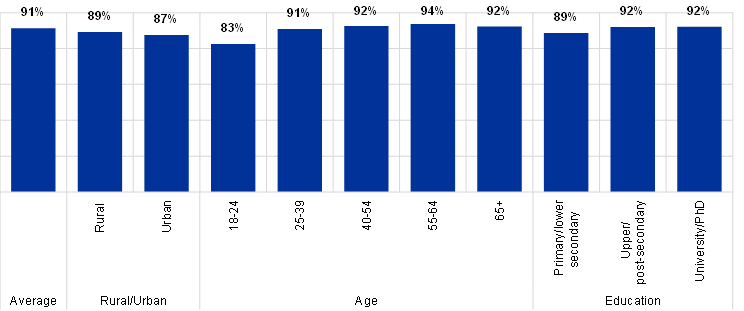

Survey responses show that in most countries the younger segment of the population (18-24) is less likely to hold payment accounts than older age groups, although this is not always the case. While holding payment accounts and payment cards often go hand in hand, it is always possible to hold one without the other; but choosing to do so will limit payment options. However, when averaged out across the euro area, there was only a slight discrepancy between those holding payment accounts (91%) and those holding cards (94%). It could be that people use prepaid cards for which no account is needed, or credit cards may be linked to accounts held by other family members, such as parents or spouses. Interestingly, a small percentage of people in most countries in most age groups responded that they did not hold payment accounts, payment cards or crypto assets. It is reasonable to suppose that these people rely largely on cash for payments, although they might rely on friends or family members whenever they need to pay with something other than cash, for example when purchasing online. Overall, twice as many age cohorts across all countries were more likely to hold a payment card than a payment account; but the differences were sometimes small.

The results show only very slight differences between the shares of the rural and urban population with access to payment accounts and cards (see Chart 32). For example, a small urban-rural gap was observed in access to payment accounts (87% in urban areas and 89% in rural areas) and access to cards (91% in urban areas and 92% in rural areas). There was also an identical difference of 2 percentage points across payment accounts and cards at all education levels: 89% of the population with primary/lower-secondary education held a payment account and 91% a card, while 92% of the population with both upper-secondary and university/PhD/research education had a payment account and 94% a card. These small differences make it difficult to tell from the statistics alone whether a greater preference for cards over payment accounts is associated with the level of education or rurality, and hence further research on this topic is encouraged.

Chart 32

Share of respondents with access to an account for payments or a card, by demographic

(percentages)

Account for payments

Card

Sources: ECB, De Nederlandsche Bank and the Dutch Payments Association (2022) and Deutsche Bundesbank (2022).

Note: The survey question was: “Which of the following do you have? 1. An account from which you can make payments; 2. Card (debit card or credit card)”.

A key goal of the Eurosystem’s retail payments strategy[35] is full deployment of Single Euro Payments Area Instant Credit Transfers (SCT Inst), i.e. instant payments[36]. These can be defined as retail payments that are processed in real time, 24 hours a day, 365 days a year, with funds made available immediately for use by the recipient.[37]

The perceived availability of instant payments was highest in Luxembourg (63%) and lowest in Greece (33%). In the Netherlands and Estonia, countries typically associated with more digitalised forms of payment, 36% and 19% respectively of the population had not heard of the service.[38] This may be attributable to respondents not knowing what SCT Inst is, being unaware that it is the default in their market or conflating it with another means of payment; the data provide no clear indication. Overall, the euro area average (Chart 33) points to 51% of the population with perceived access to instant payments, with 22% having stated that the service is not available to them.[39]

Chart 33

Share of consumers that have access to instant payments, by country

(percentages)

Sources: ECB, De Nederlandsche Bank and the Dutch Payments Association (2022) and Deutsche Bundesbank (2022).

Notes: The survey question was: “Instant payments are a special type of credit transfer that enable payers to transfer money within seconds to any payee and for which no payment cards are used or needed. Is this type of service available to you?”.

“Heard of service” refers to the answer option “I have heard about this service, but I do not know whether it is available for me or not”.

Please note that the calculations here for Germany differ from those in Deutsche Bundesbank (2022), which only asked respondents with access to online banking. In the SPACE data, respondents with no access to online banking are deemed not to have access to instant payments.

One factor assessed in the survey was whether users pay fees for instant payments (Chart 34). There are considerable differences between countries. 95% of respondents in Cyprus and 89% in Spain said they pay either no fee or the same fee as for credit transfers, but only 46% of respondents in Germany gave the same answer. This may be partly because almost one-third of German respondents did not know whether they paid a fee, which was the highest percentage in any of the countries surveyed. However, 38% of people in Italy and 23% in Germany paid a higher fee for instant credit transfers. Italy was also the only country where more people reported paying higher fees for instant credit transfers than reported paying no fees at all.

Chart 34

Share of respondents that pay a fee for instant payments, by country

(percentages)

Sources: ECB and Deutsche Bundesbank (2022).

Notes: The survey question was: “Which of the following applies to fees for your ´instant payments´?”. Since most Dutch consumers have access to a bank account offering instant payments as standard rather than a premium service, this question was not asked in the Netherlands.

Box 3

Ownership of crypto assets and their use for investment and transaction purposes

The impact of crypto assets on the overall payment mix is something that was not considered in SPACE 2019. Since then they have begun to increasingly seep into the mainstream, likely assisted by the broad second-order effects of pandemic-related restrictions. In Europe this has probably also been aided by increased clarity on regulatory treatment, which might affect consumer attitudes to using and paying with them. It is therefore important to take stock of crypto-related developments and monitor them closely.

Chart A outlines overall ownership by country. Respondents were asked whether they held crypto assets. The euro area average was a modest 4% of the population, with the highest shares observed in Slovenia (8%) and Luxembourg (8%). In Slovenia, the highest percentage holding of crypto assets was in the 25-39 age group. Notwithstanding the increased attention paid to crypto assets in both popular culture and the markets, uptake among the general population is still relatively low.

Chart A

Ownership of crypto assets

(percentages)

Sources: ECB, De Nederlandsche Bank and the Dutch Payments Association (2022) and Deutsche Bundesbank (2022).

Note: The question expected a straight yes or no to ownership of crypto assets and did not investigate the size of the holding in proportion to other assets (e.g. equities or fixed income) respondents may hold.

Those who reported holding crypto assets were also asked whether they used them for payment purposes, investment purposes or both. The results vary widely between groups. However, significance was clearly placed on holdings for investment purposes, with two or three times more people in most countries owning them for investment only than for payment purposes only. Looking at the countries where investment purposes were highest in relation to the other options, the survey showed that around 18% of French consumers holding crypto assets, for example, indicated they used them as a means of payment, while 60% indicated using them as an investment vehicle. In Germany, 85% of crypto asset holders cited using them for investment purposes, 8% for payments and 7% for both.[40] In Lithuania on the other hand, 24% of people using crypto assets say they use them for payments, and 17% use them for both.