The transmission and effectiveness of macroprudential policies for residential real estate

The transmission and effectiveness of macroprudential policies for residential real estate

Published as part of the Macroprudential Bulletin 19, October 2022.

Macroprudential measures can effectively support the resilience of households and banks and help tame the build-up of residential real estate (RRE) vulnerabilities. By capping the riskiness of new loans, borrower-based measures contribute to moderating RRE vulnerabilities in the short-term and to increasing the resilience of households over the medium term. By inducing banks to use more equity financing, capital-based measures increase bank resilience in the short and medium term but are unlikely to have a significant dampening effect on RRE vulnerabilities during the upswing phase of a financial cycle. The two categories of measures are mainly complementary and many European countries have therefore implemented them in combination in recent years.

1 Introduction

Understanding the transmission channels for borrower-based measures (BBMs) and capital-based measures (CBMs) is crucial to determine the appropriate calibration and effectiveness of macroprudential policies for RRE. This article provides an overview of the key microeconomic and macroeconomic transmission channels for both categories of measures.[1] It also reviews quantitative evidence of the effectiveness of macroprudential policies for RRE, namely whether the stated financial stability policy objectives have been achieved with minimum cost to economic entities. Finally, the article focuses on the interaction and complementarity of BBMs and CBMs, given the widespread joint implementation of both categories of measures over recent years.

2 Transmission and effectiveness of BBMs

Income-based BBMs primarily improve the resilience of new borrowers, and therefore bank resilience, while collateral-based BBMs protect against RRE price corrections. Income-based measures, such as limits to debt-to-income (DTI) and debt service-to-income (DSTI) ratios, contribute to reducing the probability of default (PDs) among households by relating loans to the overall debt repayment capacity (DTI) and/or debt servicing capacity (DSTI) of households. Collateral-based measures, such as limits on loan-to-value (LTV) ratios, primarily contain the loss given default (LGD) on loans granted by reducing the unsecured portion of a loan.[2] Consequently, applying income and collateral-based measures simultaneously to new lending effectively supports borrower resilience (in particular to interest-rate and income shocks), reduces portfolio loss rates (the product of PD and LGD) and decreases the likelihood of bank default given that the resilience of household loan portfolios increases over the medium term. Additional measures (e.g. loan maturity limits and amortization schedules) may also help to prevent the adoption of longer loan maturities to circumvent DSTI limits.

Besides increasing resilience, BBMs may also contribute to taming the build-up of RRE vulnerabilities in the short run and to reducing economic volatility over the medium term. By directly constraining the origination of new high-risk household loans, BBMs (in particular income-based limits) help to reduce credit excesses and the likelihood of an adverse feedback loop between mortgage credit and real estate price growth. Income-based measures support more sustainable household indebtedness and debt service, contributing to increased household resilience when shocks materialise. This results in lower defaults on mortgage loans, reduced bank losses and a more stable lending supply. Sounder household budgets also contribute to a more stable non-housing consumption path in periods of distress, reducing macroeconomic volatility. The effectiveness of BBMs in addressing the build-up of RRE vulnerabilities is also influenced by the scope of application (e.g. all residential housing financing, irrespective of the lender, or more narrow application to banks only) and the proportion of cash transactions.

In practice, targeted BBM design elements aim to support their effectiveness, while also addressing unintended consequences. BBMs are often less stringent for first time borrowers or for owner-occupied property to ensure that market access for these borrower categories is not unduly constrained. Exemptions to the policy limits for LTV and DSTI/DTI ratios (i.e. lending standard indicators) enabling lenders to issue a proportion of new loans with lending standards above the regulatory limits may also be used to give banks greater flexibility for a more granular borrower assessment and/or to fine tune policy implementation over the different phases of a real estate cycle. Finally, stricter definitions of lending standard indicators (e.g. allowing for haircuts on house prices or subjecting debt service ratios to interest and income shocks) may increase the resilience benefits of BBMs.

Cost-benefit frameworks are often used to assess the effectiveness of BBMs. Methods to assess the effectiveness of BBMs include analyses of distributions of lending standard indicators, changes in borrower and bank default risk, and the mitigating effects on adverse macroeconomic feedback loops. BBM limits are usually set as thresholds on the upper (riskier) portion of the distribution of lending standard indicators for new loans. The choice of BBM thresholds often considers the benefit of risk mitigation (by excluding or reducing the proportion of riskier loans) against the cost of limiting credit intermediation and market access for less wealthy or lower-income borrowers. More complex approaches evaluate the loan loss reduction benefits from limiting high-risk borrowing against the short-term macroeconomic costs, often measured in terms of lower gross domestic product (GDP) growth (largely stemming from lower credit growth).[3] The quantitative evidence suggests that the a joint implementation of income and collateral-based measures can significantly increase the resilience of households (Chart 1, panel a), with the gradually improving risk characteristics of new lending flows feeding through to loan stocks over time and strengthening bank resilience (Chart 1, panel b). General equilibrium analyses found that BBMs can reduce household defaults and indebtedness as well as macroeconomic volatility.[4] Panel VAR results[5] suggest that BBMs have a somewhat greater impact on credit and house prices than capital measures do, while a meta-analysis[6] of 58 empirical studies found that BBMs had statistically significant effects on credit but generally a weaker and more imprecise impact on house prices. Some studies looking at unintended distributional implications[7] suggest that BBMs may have a limited impact on income and wealth inequality.

Chart 1

Targeted design of BBMs can effectively increase the resilience of borrowers and banks

Sources: Panel a: Giannoulakis, et al. (2022), “The Effectiveness of Borrower-Based Macroprudential Policies: A Cross-Country Perspective,” Working Paper, ECB, Frankfurt am Main, forthcoming.

Notes: Panel a: Median and interquartile range across countries of the simulated aggregate household PDs in 19 EU countries. The green bar refers to the PDs without BBMs in place, the dark blue bars refer to the first-round (1st) impact of BBMs on simulated PDs (i.e. PD reduction via safer loan characteristics), while the light blue bars also take into account second-round (2nd) macroeconomic effects from the policy induced negative credit demand shock. Panel b: Simulated household PDs and LGDs are attached to the mortgage exposures of the banking systems across the sample of EU countries, with pass-through into the regulatory PDs and LGDs of the internal ratings-based risk weighting formula assumed at 100%.

3 Transmission and effectiveness of CBMs

CBMs generally induce banks to increase their capital ratios and thus enhance banking system resilience. As explained in the lead article, more resilient institutions are better able to absorb losses while maintaining the provision of key financial services when risks materialise, which helps to prevent the detrimental amplification effects that can occur if banks deleverage excessively in crisis times.

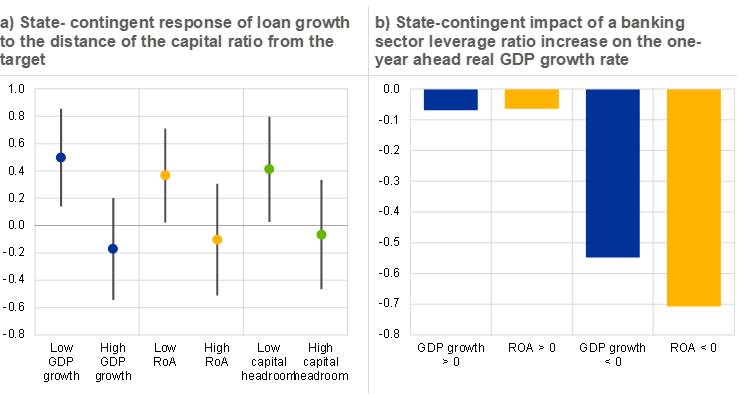

While CBMs increase resilience and enhance banks’ capacity to absorb shocks, they are unlikely to have a major dampening effect on real estate vulnerabilities during the upswing phase of a financial cycle. When macro-financial conditions are favourable, banks can adapt to higher capital requirements by retaining earnings or raising new equity, making it unlikely that they will need to constrain credit supply in order to meet higher requirements.[8] Microeconometric evidence suggests that the effects of higher capital requirements are very modest when banks are profitable, have comfortable headroom above their capital requirements, or when economic conditions are favourable (Chart 2, panel a).[9] Since these conditions are likely to be met during financial cycle upswings, increasing capital buffer requirements in such times is unlikely to have a significant dampening effect on credit supply. Correspondingly, the short-term costs in terms of reduced economic activity due to lower credit supply are expected to be limited when CBMs are activated during expansions (see Chart 2, panel b). In contrast, during sharp economic downturns and crises, banks are much more likely to become capital constrained. Consequently, the availability and in particular the release of CBMs during such downturn periods can help to ease capital constraints and facilitate the continuous provision of key financial services to the real economy (see Chart 2).[10] This in turn reduces medium-term macroeconomic volatility through a more stable credit supply.

Chart 2

Activating CBMs during expansions is unlikely to have big economic costs, while their release in downturns increases banks’ loss-absorption capacity and supports credit supply

Sources: ECB and ECB calculations.

Notes: Panel a:: The chart displays coefficients from bank-level panel regressions covering data for 42 European banking supervision significant institutions over the period from 2016-Q1 to 2019-Q4, building on the regression setup and data set out in Couaillier,C. (2021), “What are banks' actual capital targets?”, Working Paper Series, No. 2618, ECB, Frankfurt am Main, December. The dependent variable is the quarterly corporate loan growth rate. The displayed coefficient estimates are for interaction terms between a bank’s distance to its capital ratio target and dummy variables indicating whether GDP growth, profitability or capital headroom are below of above the sample median. Grey lines represent confidence intervals at the 95% level. The regressions also include several bank-specific and macroeconomic control variables. A positive coefficient implies that loan growth is lower when the bank’s capital ratio is below its target capital ratio. RoA stands for return on assets.

Panel b: The chart displays the state-contingent response of the one-year ahead real GDP growth rate to a 1 percentage point increase in the banking sector leverage ratio (measured as total capital divided by total assets), differentiated according to whether current real GDP growth and the banking sector return on assets are positive or negative. The results are based on panel local projections for euro area countries.

Various CBMs are available to address RRE-related risks and the choice of instrument depends on the precise nature of the risks to be tackled. The countercyclical capital buffer (CCyB) is the broadest cyclical instrument, appropriate when real estate vulnerabilities are accompanied by other cyclical vulnerabilities or could spill over to other economic sectors. By contrast, sectoral CBMs increase resilience in a more targeted manner by applying higher buffer requirements or risk weight policies only to relevant mortgage exposures. Consequently, sectoral CBMs are more appropriate when vulnerabilities are confined to the RRE sector. With regard to sectoral CBMs, the same aggregate capital impact can be achieved by applying different types or combinations of instruments, meaning that the measures are partly substitutable (see Focus 4 linking sectoral risk weight policies to capital buffers and leverage ratios). However, the impact of different instruments may vary across institutions, and the nature of vulnerabilities may call for a specific instrument (combination).[11] Finally, the choice of instruments also depends on legal aspects, given that European legislation requires authorities to explain, in some cases, why a specific risk cannot be addressed with another instrument (i.e. resulting in a “pecking order”).[12]

Cost-benefit frameworks are also used to analyse the effectiveness of CBMs. Methods range from stress-test approaches focusing on the benefits of higher bank capital ratios for withstanding losses from adverse scenarios[13], to macroeconometric methods comparing the resilience benefits of higher capital requirements against the costs of constraining credit and output, to general equilibrium approaches looking at the net benefits in steady state.[14] Given the fungibility of capital, many papers focus on the effects of higher capital, without differentiating by type of capital requirement. For example, some general equilibrium and macroeconometric approaches find that a better capitalised banking sector leads to lower total credit volatility given that the financial sector is then less prone to default and can therefore continue to provide credit to the economy under adverse circumstances; however, they also find that the impact of increasing macroprudential capital requirements on taming the build-up of vulnerabilities is limited (e.g. in comparison with BBMs).[15] That finding is also confirmed by empirical analysis focusing on the effects of higher sectoral capital requirements in the real estate sector, this analysis also finding that the effects on mortgage quantities and prices are relatively modest.[16]

4 Consideration of the interactions between BBMs and CBMs

BBMs and CBMs mostly complement each other in enhancing banking sector resilience. BBMs affect the flow of new mortgages and limit the further build-up of vulnerabilities by improving borrower risk profiles. This gradually supports safer household loan portfolios given that less risky new loans gradually replace the riskier portion of outstanding stocks. CBMs are needed in the short run to enhance resilience against vulnerabilities already accumulated in the existing loan stock.

Because of their gradual impact on resilience, BBMs can partly substitute for CBMs but only over the medium term. However, the regulatory framework automatically captures the partial substitutability between BBMs and CBMs over the medium term, at least to a certain degree. This is because the improved risk characteristics of newly originated mortgages through binding BBMs should pass through into regulatory PDs and LGDs and decrease risk-weighted assets (RWAs), consequently also the nominal amount of required capital for a given capital buffer rate.[17] This feature of the regulatory framework already accounts for the fact that BBM implementation can lower future credit risk-related losses from retail mortgage loans, thereby achieving the same level of system resilience with somewhat lower capital levels. Model-based simulations suggest that these effects can be material, with a 1 percentage point median improvement in the capital ratio across banking systems in the sample, resulting from the joint implementation of LTV, DSTI and DTI macroprudential limits, this effect largely being due to the improvement in RWAs (Chart 1, panel b).[18]

CBMs linked to lending standards (hybrid CBMs) can help to target specific sources of systemic risk but are unlikely to substitute for the direct effect of BBMs of dampening excessive mortgage loan growth. Hybrid CBMs are macroprudential risk weight or capital buffer policies that are differentiated based on the lending standards for a particular exposure (namely, the LTV, DSTI, or DTI ratios), with the aim of requiring more additional capital for riskier exposures.[19] While these measures may potentially be easier to activate than BBMs and can of course be effective in enhancing bank resilience in a targeted way, they are unlikely to substitute for BBMs in terms of impact on new mortgage flows. Specifically, given the standard estimated elasticities of mortgage loan demand to interest rates, the calibration of “hybrid” capital measures may need to be prohibitively high to obtain the material reduction in the origination of risky loans and lending growth achieved by BBMs. Simple calculations indicate that even high capital buffer surcharges on “risky” loans (for example, 10 percentage points) would only lead to moderate increases in the pricing of the loans affected (for example, +15 basis points) for standard ranges of internal ratings-based (IRB) retail mortgage loan risk weights, and hence would be unlikely to lead to big reductions in risky loan origination.

In conclusion, both BBMs and CBMs can be effective in supporting financial stability objectives, especially if used in conjunction. Many considerations, ranging from the legal availability of instruments, through the challenges of the complexity of their (joint) calibration, to the timing of activation and possible recalibration during the RRE cycle, may ultimately affect the choice of instrument combinations. The use of combinations of BBMs ensures that multiple aspects of systemic risk related to households are addressed and reduces the scope for circumvention, thereby enhancing their individual effectiveness. Given their overlapping transmission channels, the various capital measures primarily reinforce each other and, in some cases, combining them may enhance their effectiveness. Finally, combining BBMs and CBMs ensures comprehensive coverage of different systemic risks and generates important synergies.

References

Ampudia, Miguel, Lo Duca, Marco, Farkas, Mátyás, Pérez-Quirós, Gabriel, Pirovano, Mara, Rünstler, Gerhard and Tereanu, Eugen (2021), “On the effectiveness of macroprudential policy”, Working Paper Series, No 2559, ECB, Frankfurt am Main, May.

Araujo, J., Patnam, M., Popescu, A., Valencia, F. and Yao, W., (2020), “Effects of Macroprudential Policy: Evidence from Over 6,000 Estimates”, Working Paper, No 2020/067, International Monetary Fund, Washington, 22 May.

Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (2018), “Towards a sectoral application of the countercyclical capital buffer: A literature review”, Working Paper, No 32, Bank for International Settlements, Basel, March.

Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (2019), “The costs and benefits of bank capital – a review of the literature”, Working Paper, No 37, Bank for International Settlements, June.

Basten, Christoph (2020), “Higher Bank Capital Requirements and Mortgage Pricing: Evidence from the Counter-Cyclical Capital Buffer”, Review of Finance, Vol. 24, March, pp. 453-495.

Behn, Markus, Lang, Jan Hannes and Tereanu, Eugen (2022), “Transmission and effectiveness of capital-based macroprudential policies”, Financial Stability Review, ECB, Frankfurt am Main, May.

Budnik, Katarzyna, Balatti, Mirco, Dimitrov, Ivan, Groß, Johannes, Kleemann, Michael, Reichenbachas, Tomas, Sanna, Francesco, Sarychev, Andrei, Sinenko, Nadežda and Volk, Matjaz (2020), “Banking euro area stress test model”, Working Paper Series, No 2469, ECB, Frankfurt am Main, September.

Couaillier, Cyril (2021), “What are banks' actual capital targets?”, Working Paper Series, No 2618, ECB, Frankfurt am Main, December.

Couaillier, Cyril, Lo Duca, Marco, Reghezza, Alessio, Rodriguez d’Acri, Costanza and Scopelliti, Alessandro (2021), “Bank capital buffers and lending in the euro area during the pandemic”, Financial Stability Review, ECB, Frankfurt am Main, November.

De Nederlandsche Bank (2019), “Financial Stability Report - Autumn 2019”, Amsterdam, 15 October.

Ferrari, Stijn, Pirovano, Mara and Kaltwasser, Pablo Rovira (2016), “The impact of sectoral macroprudential capital requirements on mortgage loan pricing: evidence from the Belgian risk weight add-on”, Working Paper, No 306, National Bank of Belgium, Brussels, October.

Galati, Gabriele and Moessner, Richhild. (2018), “What do we know about the effects of macroprudential policies?”, Economica, Vol. 85, Issue 340, 9 March, pp. 735-770.

Georgescu, Oana-Maria and Vila Martin, Diego (2021), “Do macroprudential measures increase inequality? Evidence from the euro area household survey”, Working Paper Series, No 2567, ECB, Frankfurt am Main, June.

Giannoulakis, Stelios, Forletta, Marco, Gross, Marco and Tereanu, Eugen (2022), “The Effectiveness of Borrower-Based Macroprudential Policies: A Cross-Country Perspective”, Working Paper, ECB, Frankfurt am Main, forthcoming.

Gross, Marco and Población, Javier (2017), “Assessing the Efficacy of Borrower-Based Macroprudential Policy Using an Integrated Micro-Macro Model for European Households”, Economic Modelling, Vol. 61, pp. 510-528.

Jurča, Pavol, Klacso, Ján, Tereanu, Eugen., Forletta, Marco and Gross, Marco (2020), “The Effectiveness of Borrower-Based Macroprudential Measures: A Quantitative Analysis for Slovakia”, IMF Working Paper, No 2020/134, International Monetary Fund, Washington, 17 July.

Lang, Jan Hannes, Izzo, Cosimo, Fahr, Stephan and Ruzicka, Josef (2019) “Anticipating the bust: a new cyclical systemic risk indicator to assess the likelihood and severity of financial crises”, Occasional Paper Series, No 219, ECB, Frankfurt am Main, February.

Neugebauer, Katja, Oliveira, Vitor and Ramos, Ângelo (2021). “Assessing the Effectiveness of the Portuguese Borrower-Based Measures in the Covid-19 Context”, Working Paper, No 10/2021, Banco de Portugal, Lisbon.

For details of the measures, see the lead article in this edition of the Macroprudential Bulletin.

By increasing borrowers’ “skin in the game”, they also limit the incentives for strategic default in jurisdictions where banks do not have full recourse to all the borrowers’ assets.

See, for example, Giannoulakis et al. (2022).

See Araujo et al. (2020).

For further discussion of the precise transmission channels, see Behn et al. (2022).

Banks’ capital ratio targets depend, inter alia, on their capital requirements (see Couaillier (2021)); consequently an increase in capital requirements increases targets and therefore reduces the difference between actual and targeted capital ratios (“distance to target”). The regression coefficients in Chart 2a show that any such reduction in distance to target exerts a significantly negative impact on corporate loan growth, but only when GDP growth, return on assets or capital headroom are below the sample median, respectively. When these three variables are above the sample median, an increase in capital requirements, which would reduce banks’ distance to capital targets, does not lead to statistically significant reductions in corporate loan growth.

For evidence of the functioning of these mechanisms during the pandemic, see Couaillier et al. (2021).

For example, risk weight floors can serve as a backstop to address potentially unwarranted heterogeneity in internal ratings-based mortgage risk weights and will affect institutions heterogeneously, whereas the sectoral systemic risk buffer (sSyRB) increases requirements in proportion to risk-weighted assets for relevant real estate exposures (and can be released during crises, similar to the CCyB). To achieve the desired increase in resilience for each institution, a combination of instruments may be warranted.

For example, under Article 458 of Capital Requirements Regulation (CRR) No. 575/2013, authorities are required to provide justification for why the risk weight measures under Art. 124/164 CRR, measures under Pillar 2, or a sSyRB or a CCyB cannot adequately address the systemic risk identified, taking into account the relative effectiveness of those measures.

For a review of the literature on costs and benefits of higher bank capital requirements, see Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (2019).

See, for example, Ferrari et al. (2016) or Basten (2020). While the empirical literature on the effects of higher capital requirements is very rich, papers that look at sectoral requirements specifically are scarcer. A comprehensive overview of the literature on sectoral requirements is provided by BCBS (2018).

In practice, this pass-through may be imperfect as regulatory through-the-cycle PDs and downturn LGDs may not be sufficiently sensitive to changes in loan risk characteristics due to a low default history.

See Giannoulakis et al. (2022).

For example, De Nederlandsche Bank recently activated an LTV-dependent risk weight floor on IRB retail mortgage loan exposures, using Art 458 CRR (see De Nederlandsche Bank (2019)).