Communication for financial crisis prevention: a tale of two decades

Published as part of the Financial Stability Review, November 2024.

This edition of the ECB’s Financial Stability Review (FSR) marks the 20th anniversary of its inaugural publication. The FSR was originally launched to help in preventing financial crises, and this special feature draws lessons from two decades of experience in identifying, analysing and communicating about systemic risks via this publication. Although risk analysis and risk communication are distinct processes, the special feature emphasises that they are inextricably intertwined in a seamless cycle where each informs and enhances the other. Effective risk identification is founded on the ability to combine structured, data-driven assessments with qualitative insights and expert judgement. Such an approach requires a comprehensive and adaptive framework that continuously integrates broad reviews of indicators with focused analyses on emerging risks. Early identification of vulnerabilities enables timely intervention, but the complex, non-linear way that the financial system functions means that flexibility remains essential. Clear and transparent communication of systemic risks supports this analytical process by shaping expectations and enhancing market discipline, creating a feedback loop that strengthens both policy response and risk awareness. However, central banks face the challenge of balancing communication frequency and depth in order to avoid false alarms while at the same time maintaining credibility. As the ECB’s FSR has evolved, it has sought to become more accessible and data-driven, while utilising diverse media channels to broaden its audience. Experience confirms that targeted, proactive communication reinforces financial stability by aligning policymakers and markets, underscoring the symbiotic relationship between risk analysis and effective communication in maintaining financial system resilience.

1 Introduction

The European Central Bank (ECB), like all central banks, has a strong and natural interest in safeguarding financial stability as reflected in its mandate.[2] There is a long history of central banks prioritising financial stability as a core aspect of their mandates, with at least three reasons explaining this involvement. First and foremost, the aim is to prevent financial crises which could have severe consequences for the real economy. As central banks are integral to the functioning of the financial system, they have ready access to timely information, making them uniquely placed to detect and monitor sources of risk and vulnerabilities affecting financial stability. If required, central banks can communicate about the consequences of private sector inaction in managing systemic risks. If this proves ineffective, they can activate prudential policy instruments to mitigate such risks before they crystallise and escalate into crises which impair financial intermediation.[3] This crisis prevention role has grown in importance since the global financial crisis as many central banks have taken on macroprudential policymaking responsibilities.[4] Second, central banks are often endowed with responsibilities as lenders of last resort, which allows them to provide liquidity to financial institutions during times of stress. This role is crucial in ensuring that financial institutions can meet their obligations, thereby preventing multiple bank failures and shielding the economy from systemic risks.[5] Third, it is broadly acknowledged that financial stability is essential for the effective implementation of monetary policy and for the smooth operation of payment systems. Financial instability can lead to disruptions in the economy, and if such disruptions are sufficiently severe to cause panic, they can undermine the willingness of banks to lend. By contrast, when a financial system is stable, credit flows smoothly from lenders to borrowers, allowing central banks to influence economic activity and inflation by changing interest rates.

This special feature presents a stylised overview of the ECB’s framework for identifying euro area-wide systemic risks and its approach to communicating them in its semi-annual Financial Stability Review. The rest of this special feature is organised as follows: Section 2 briefly presents the role of risk identification and communication as distinct, but intertwined processes. Section 3 outlines the ECB’s framework for identifying systemic risks, while Section 4 discusses central bank communication about systemic risks. Section 5 concludes.

2 Systemic risk identification and communication as intertwined processes

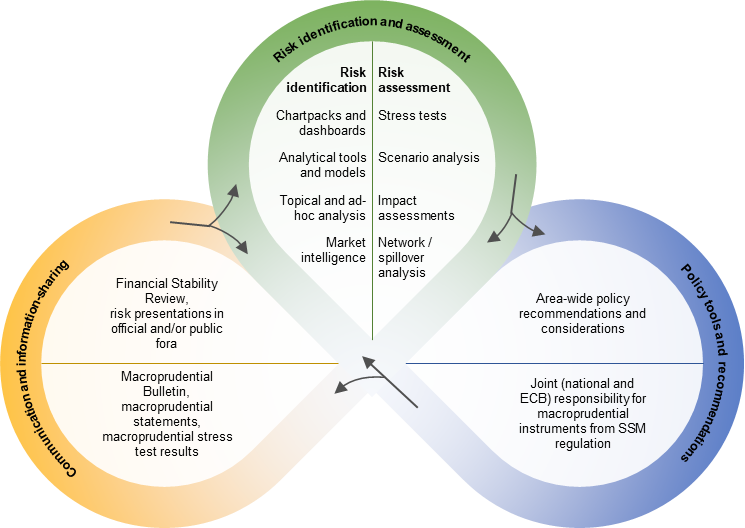

The timely and robust identification of sources of risk and vulnerabilities is fundamental for an effective financial stability analytical framework. In contrast to the price stability objective of central banks, the concept of financial stability is difficult to define and even more difficult to measure. Financial systems are usually considered stable if they are able to intermediate efficiently between savers and borrowers, while having the capacity to manage financial risks effectively and absorb shocks.[6] With so many dimensions to financial stability, no single yardstick can reasonably be expected to capture each and every one. The task is to identify sources of risk and vulnerabilities which could impair financial intermediation and effective risk reallocation within the financial system. This involves detecting and prioritising fault lines which could threaten shock-absorption capacity. As the externalities inherent to systemic risk are often complex and non-linear, an eclectic approach is needed to ensure that risk identification is effective.[7] This ranges from the systematic use of data and models, the collection of qualitative information through market intelligence and out-of-the-box, or contrarian, analysis, all of which aim to anticipate implications for a constantly evolving financial system. The timely and robust identification of emerging vulnerabilities can, in turn, inform an assessment of the materiality of individual sources of risk through the use of macro stress testing, for instance.[8] These sources of risk can then be prioritised according to the effects they may have on shock-absorption capacity as well as the potential costs for the real economy. This informs communication strategy and macroprudential policy settings (Figure A.1). One aspect which sets the ECB apart from other central banks with macroprudential responsibilities is that they have a specific country focus. In practice, this means that the ECB needs to constantly cross-check the findings from top-down area-wide analyses of sources of risk and vulnerabilities against the findings from country-level analyses.[9] All in all, with an emphasis on what can go wrong, input from the various building blocks for identifying risks is crucial for the ECB to form a robust prioritisation of sources of risk and vulnerabilities and to decide on the appropriate communication strategy.

Central bank communication on financial stability and systemic risks plays an important role in safeguarding financial stability. While communication on threats to financial stability is a separate process from analysis, the two are inextricably intertwined in a seamless cycle where each informs and enhances the other (Figure A.1). Communication forms an important part of crisis prevention as it helps shape expectations. In turn, these expectations can bring about preventive action within the financial industry, strengthen market discipline and enhance the financial system’s resilience. Furthermore, financial stability communication allows central banks to be transparent and ensures accountability as they carry out their financial stability duties. It can also foster financial inclusion and a better understanding of financial risks.

Figure A.1

Risk identification and communication are inextricably intertwined in the ECB’s financial stability analysis and macroprudential policy processes

Source: ECB.

3 Systemic risk identification: mission impossible?

Systemic risk refers to the possibility that the provision of financial products and services by the financial system could be impaired so severely that economic growth and welfare would be materially affected.[10] It can arise from at least three sources, including an endogenous build-up of financial imbalances, sizeable adverse aggregate shocks to the economy or the financial system, and contagion across markets, intermediaries or infrastructures. While systemic risk is not a phenomenon limited to financial systems, some characteristics of such systems make them particularly prone to systemic risk.[11] First, the financial system is characterised by important externalities (see footnote 7). Complex and dynamic networks of exposures among major financial intermediaries usually facilitate efficient risk-sharing mechanisms in tranquil times but they can become a source of instability in periods of stress.[12] Second, the prevalence of asymmetric information in the financial system creates agency problems between counterparties which may not be fully captured by underlying financial contracts. Third, powerful feedback and amplification mechanisms − such as market illiquidity, maturity mismatches between assets and liabilities and leverage − increase the risk of shocks becoming more severe and more widespread.[13]

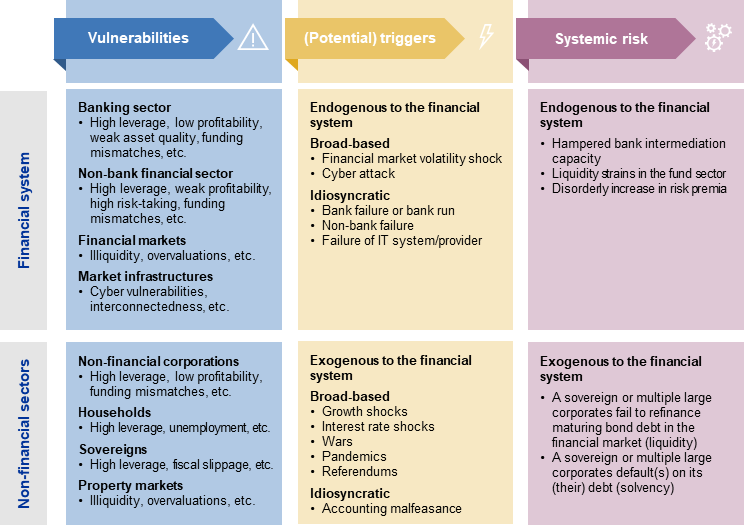

Figure A.2

Operationalisation of a risk identification framework requires a thorough understanding of subtle differences between vulnerabilities, triggers and risks

Source: ECB.

Conceptually, it is crucial to distinguish between vulnerabilities, triggers which could unravel them and systemic risk scenarios, or narratives, which describe how financial crises play out.[14] Vulnerabilities are imbalances or fault lines which reduce the financial system’s capacity to absorb the impact of negative events. They often represent structural and fundamental weaknesses within the financial system and non-financial sectors which can propagate and amplify shocks. A trigger is an event that could unearth or catalyse the unravelling of a vulnerability. Triggers of financial stress can originate from either within or outside the financial system and can be broad-based or idiosyncratic in nature (Figure A.2). Depending on the resilience of the financial system, triggers can, if activated, have limited and manageable effects or they can unleash systemic financial crises. Risk scenarios bring together identified vulnerabilities and plausible triggers into a coherent and consistent framework that can describe and potentially quantify the main channels of systemic risk propagation. Such scenarios often involve the unravelling of several vulnerabilities simultaneously, as imbalances and fault lines are often interlinked. For example, a disorderly rise in risk premia could unearth vulnerabilities in different economic and financial sectors if there are cross-exposures to assets with compressed valuations and if funding is available at very low cost. The main concern over a situation becoming systemic is thus not that a single financial institution would face distress if asset prices were to fall, but that several financial institutions would be confronted with liquidity and/or solvency challenges at the same time.

The ECB takes a medium-term perspective when considering vulnerabilities and systemic risk scenarios. Ideally, sources of risk and vulnerabilities should be identified at an early stage to allow for swift communication and appropriate remedial action to be taken by the financial industry. For macroprudential policymaking, the horizon is often longer, for two reasons. First, corrective actions taken by the financial industry, if any, may reduce vulnerabilities and address systemic risks. Second, the amount of time needed to activate some macroprudential policy tools can be lengthy. For instance, a change of setting for the countercyclical capital buffer must be communicated to banks one year before it enters into effect.

Seminal early work laid the conceptual basis for financial stability frameworks, but costly financial crises have highlighted the need for refinement. Work done in the early 2000s provided the essential conceptual foundations needed to build robust analytical frameworks for financial stability.[15] Later on, major bouts of financial instability, especially the global financial crisis of 2007-09, revealed several blind spots, including interconnections within the financial system that had not been properly detected, let alone measured. At the same time, lessons learned from this and other crisis episodes underscored the need for a framework that is sufficiently agile to adapt to a financial system that is constantly evolving. Efforts made after the global financial crisis to enhance the collection and availability of data for financial stability purposes have also been bearing fruit, and it is now possible to conduct analyses that were not possible before.

There is no one best way to organise a financial stability risk identification framework. Several factors need to be considered when designing a framework for financial stability risk detection, including the financial system’s structure, the relative importance of different sectors in the economy and policymakers’ preferences. A framework could, for example, be organised around types of vulnerability that proved to be sources of risk during past crises (such as excessive leverage, asset-liability mismatches and asset price misalignments).[16] Alternatively, it could be organised around the monitoring of different sectors within the financial system and the non-financial sector. Each approach has its pros and cons. A sectoral approach, while comprehensive, requires an additional analysis of the interactions and interconnectedness of vulnerabilities across sectors. Conversely, a framework based on familiar vulnerabilities offers a cross-sectoral span, but it risks being less comprehensive and might even miss newly emerging vulnerabilities.

The ECB follows a sectoral approach in its euro area-wide systemic risk identification framework. This covers (i) the non-financial sector, including sovereigns, non-financial corporations, households and property markets; (ii) financial markets; (iii) the banking sector; and (iv) the non-bank financial intermediation sector, with a focus on investment funds, insurance corporations and pension funds. This approach ensures the comprehensive monitoring of all parts of the financial system and the environment in which financial intermediaries operate. It also facilitates the development of tailored indicators and models for each sector. For the ECB, it is important to form a comprehensive overview of banking sector vulnerabilities, as its macroprudential powers are limited to “topping-up”, or being more stringent in the activation of, measures taken by national macroprudential authorities for their banking sectors.

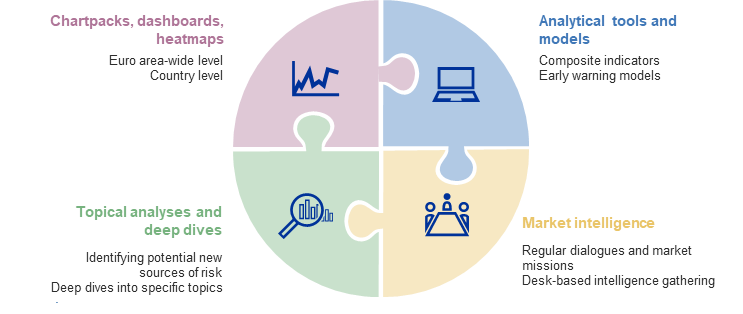

Figure A.3

The four building blocks of the ECB’s systemic risk identification framework comprise various monitoring and analytical tools, topical deep dives and market intelligence

Source: ECB.

More specifically, the ECB’s systemic risk identification framework consists of four main complementary and interlinked building blocks. A thorough sweep of the latest developments serves as a starting point for risk identification. This is complemented by a systematic review of analytical tools and models to ensure the structured monitoring of developments and the assessment of risks. Topical analyses and deep dives, together with market intelligence-gathering, help detect potential sources of risk that might otherwise go undetected, e.g., due to measurement problems (Figure A.3). These building blocks are complementary since they cross-check a variety of information sources and combine them into a comprehensive view on sources of risk. For example, a deep-dive analysis of a new development that is relevant to financial stability (e.g. a financial innovation) could lead to more structural adjustments to regular monitoring. It could also prompt the adaptation of existing (or the development of new) analytical indicators to facilitate ongoing risk monitoring. Input from each of the four building blocks is crucial for forming a robust prioritisation of vulnerabilities and for deciding on the appropriate communication strategy.

4 Financial stability communication: more than words

4.1 Communication challenges

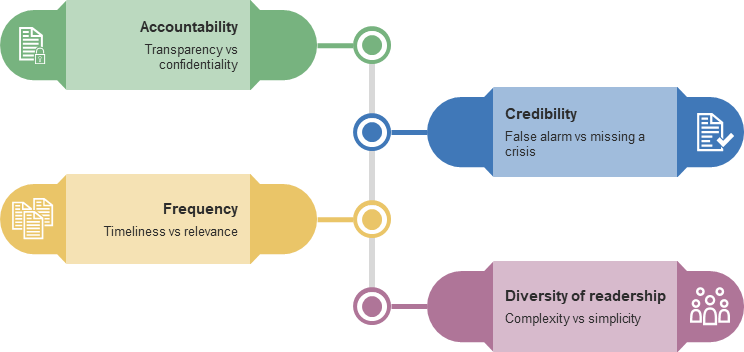

Central banks face challenges associated with accountability, credibility and the frequency and accessibility of communication when designing a financial stability communication strategy. With regard to accountability, while financial stability communication has become more transparent over the past two decades, central banks need to be careful not to trigger identified risks by overstating them, while also ensuring that they do not underplay vulnerabilities.[17] At the same time, the credibility of central banks’ financial stability assessments may be compromised if communication on sources of risk and vulnerabilities is either too early, thereby raising false alarms (known as a type II error), or too late, thereby missing a crisis (a type I error). The frequency of communication also matters. If it is too frequent, it could undermine urgency and have less impact, while if it is not frequent enough, it could be out of date or too late in communicating about sources of risk. Finally, central banks need to reach a diverse audience, including policymakers, industry professionals, academics and the general public. This requires a layered communication strategy to ensure that the right information is presented to the right audience (Figure A.4).[18]

Figure A.4

Central banks need to make a number of trade-offs to ensure their financial stability communication is credible, timely and suitable for target audiences

Source: ECB.

4.2 Financial stability reports: the nuts and bolts of financial stability communication

Central banks across the globe use financial stability reports (FSRs) as a primary tool for communication about the resilience of their financial systems. The publication of FSRs began in the second half of the 1990s, with central banks in the United Kingdom, Norway and Sweden leading the way (Chart A.1, panel a). These central banks started publishing FSRs in response to banking crises in the early 1990s. Since then, the number of central banks publishing FSRs has grown rapidly.[19] Most produce them twice a year, although some only publish once a year. Publication frequency may change over time though, as in the case of Norges Bank and the Bank of Canada, for instance. These changes can also be temporary, e.g. to meet the need for enhanced communication during major crises as done by some institutions during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020-21.

Chart A.1

Central banks publish financial stability reports to provide information to their stakeholders and to improve general awareness of financial stability risks

a) Start dates and publication frequency of FSRs by selected central banks | b) Topics of interest to the public related to the ECB’s work |

|---|---|

(1994-2024) | (2023, percentage share of respondents) |

|  |

Sources: ECB and the ECB Knowledge and Attitudes Survey 2023.

Notes: Panel a: BoE: Bank of England, BoC: Bank of Canada, IMF: International Monetary Fund, BdE: Banco de España, BdF: Banque de France, ECB: European Central Bank, DnB: De Nederlandsche Bank, BoJ: Bank of Japan, Buba: Deutsche Bundesbank, BdI: Banca d’Italia, FED: Federal Reserve System. Triannual frequency resulted from interim FSRs or financial stability updates during the COVID-19 pandemic.

FSRs help create more stable financial environments and enhance the understanding of financial risks. Taking a market perspective, the literature suggests that FSR releases can move equity markets by more than 1% in the month after publication. They can also help to reduce noise, as market volatility tends to fall following the publication of an FSR. These effects are particularly strong when FSRs include an optimistic assessment of financial stability risks.[20] When it comes to understanding the financial system and financial risks, the ECB Knowledge and Attitudes Survey 2023[21] finds that the general public is very interested to learn about the ECB’s assessment of financial stability (Chart A.1, panel b). A recent survey of readers of the ECB’s FSR underscores these results (Box A).

Like other central banks, the ECB regularly communicates its views on financial stability vulnerabilities to various internal and external stakeholders. The main purpose of the ECB’s communication is to ensure that policymakers, the financial industry and the public at large are aware of systemic risks. The ultimate goal is to promote financial stability. Communication around identified sources of risk and vulnerabilities also forms part of the ECB’s macroprudential and microprudential competences. A financial system-wide assessment of risks and vulnerabilities is not only a key aspect of the ECB’s internal country-level macroprudential policy analysis, it also complements the microprudential supervision of individual banks.

The ECB’s work on risk identification is communicated via various channels, with the Financial Stability Review as the flagship. The ECB communicates information on financial stability through (i) regular reports and notes; (ii) presentations of analytical work to various European and international fora; (iii) public speeches and presentations; and increasingly (iv) social media, podcasts and blogposts. The ECB’s flagship publication on financial stability risks is its semi-annual Financial Stability Review, which has been published since December 2004.[22] It provides an overview of potential risks to financial stability in the euro area.[23] It contains a detailed review of trends and developments, including vulnerabilities, in the non-financial sectors, financial markets, the banking sector and the non-bank financial intermediation sector. It also highlights general policy implications. The overall assessment of financial stability conditions, risks and vulnerabilities is presented in an overview.

Box A

Results from the May 2024 FSR readership survey

The ECB ran a survey among readers of its FSR to gauge its effectiveness as a communication tool. In anticipation of the 20th anniversary of its inaugural FSR, the ECB conducted a readership survey in parallel with the publication of the May 2024 issue. The survey was circulated to known regular readers such as experts in national central banks, market intelligence contacts and journalists. It was also made accessible via the ECB’s website to anyone who viewed the FSR. In total, 86 responses were submitted.[24] The majority of respondents were employed by central banks and the financial industry (Chart A, panel a, left graph). While fewer responses were provided by readers working in other fields, the results confirmed that there was also some interest in the FSR in academia, international organisations, the media, the public sector (other than central banks) and among risk managers from outside the financial industry. In addition, most respondents have read the FSR at least regularly (many frequently or always) over the last five years, indicating that readers have retained an interest in financial stability matters (Chart A, panel a, right graph).

Chart A

Readers of the FSR are mostly employed in the financial and public sectors, read the FSR regularly and largely agree with the analysis presented in the FSR

a) Professional role of respondents and their frequency of reading the FSR over the past five years | b) How much do you agree or disagree with each of the following statements? |

|---|---|

(May 2024, percentage of respondents) | (May 2024, percentage of respondents) |

|  |

Source: ECB.

Respondents largely agree with the FSR’s financial stability assessments, with some potential to improve the tone on some risks. The first question asked about the extent to which respondents agreed that the FSR (i) identifies relevant risks to euro area financial stability, (ii) overstates some financial stability risks, (iii) understates some financial stability risks, (iv) signals risks of which respondents were not aware of, and (v) identifies relevant trends in the financial sector apart from risks (Chart A, panel b). Over 90% of respondents agreed at least somewhat that the FSR identifies relevant risks; majorities of 80% and almost 70% respectively stated that the FSR identifies relevant trends apart from risks and that they were not aware of some of the risks identified in the FSR. On a more critical note, over 50% of respondents viewed some of the risks as being overstated in the FSR, while almost 40% reported that some risks are understated. This finding may indicate that the FSR could strike a better balance in the assessment of risks, although it may also reflect the complexity and uncertainty inherent in assessing potential risks, leading to differing views.

The FSR influences decision-making, especially in the areas of policy advice and processes, and when it comes to setting analytical agendas. The second question asked how much the information provided in the FSR influences respondents’ considerations related to (i) policy advice or policy processes, (ii) research projects or analytical agendas, (iii) risk management practices, and (iv) investment decisions (Chart B, panel a). While the survey does not distinguish between whether respondents simply offer opinions and advice on policy or whether they are directly involved in policy processes, over 85% of respondents reported that the FSR influences their decisions in these areas. A high level of influence was also reported for decisions on research projects and analytical agendas (90% reported some influence). For risk management practices and investment decisions, 20% of respondents reported that they are not involved in such decisions and a further 10-20% indicated that the FSR has no influence on these decisions. For investment decisions only around 15% of respondents reported a high level of influence.

Chart B

Respondents are influenced by the FSR in their decision-making and place most value on the summary assessment and topical analyses

a) How much (if at all) does the information provided in the ECB’s FSR influence your considerations related to the following decisions? | b) Generally speaking, how useful do you find the following parts of the ECB’s Financial Stability Review? |

|---|---|

(May 2024, percentage of respondents) | (May 2024, percentage of respondents) |

|  |

Source: ECB.

The format of the FSR is generally regarded as useful, particularly the Overview, data visualisations and topical analyses. The third question asked respondents how useful they find the different parts of the FSR (Chart B, panel b). Around 90% of respondents found all parts of the FSR useful, namely the Overview that provides a summary assessment, the main text that provides regular analyses, and the boxes and special features that provide topical analyses. That said, a lower share of respondents regarded the main text as “very useful”. Data visualisations in the form of charts were also seen as useful by a vast majority of respondents (93%). The underlying data that are shared on the ECB’s website are seen as the least useful element of the FSR, but still received positive feedback from around 65% of respondents.

The survey results suggest that the ECB’s FSR is well positioned to achieve its communication objectives. Bearing in mind that the primary goal of the FSR is to promote awareness of systemic risk among policymakers, the financial industry and the public at large, the results of the survey are reassuring across several dimensions. First, the composition of respondents confirms that the FSR is reaching its target audiences. Second, readers perceive the FSR’s messages as relevant and are learning about risks they were not previously aware of. Third, going beyond promoting awareness, the FSR’s messages play a role in readers’ decision-making, particularly when it comes to policy advice. Nevertheless, readers also signalled that they did not entirely agree with the balance of risks presented, so there is no room for complacency in the continuous calibration of the ECB’s financial stability communication strategy.

4.3 Feeling the pulse: adapting FSRs to a changing world

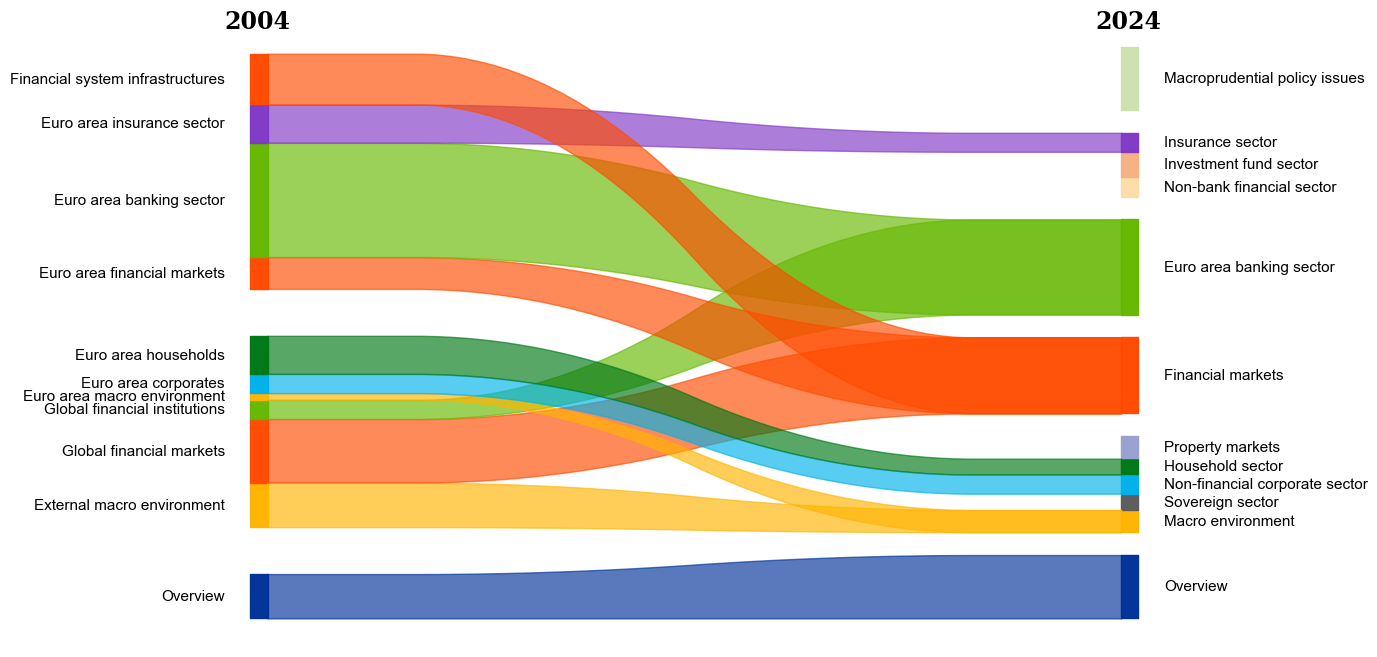

The structure and content of FSRs has changed markedly over the past two decades. Most central banks used to focus on discussing vulnerabilities in their national banking sectors, but over time they have broadened the scope of their reports to cover a wider range of sectors and topics. In contrast to the first issue published in December 2004, the latest editions of the ECB’s FSR in 2024 focus more on the euro area than on global developments and contain material that was added over the years due to a variety of reasons (Figure A.5). First, episodes of stress, such as the global financial crisis and the euro area sovereign debt crisis, led to more targeted description of vulnerabilities stemming from property markets and the sovereign sector. Second, the structural changes in the financial system arising from the growing importance of non-banks are now reflected in a standalone section on non-banks. This section discusses the trends and vulnerabilities in such institutions and their growing interconnectedness with traditional banks. Third, the ECB’s macroprudential policy mandate, which it assumed in 2014, led to the introduction of a section on macroprudential policy issues, the aim of which was to link vulnerabilities and policies. All these changes underscore the need for flexibility in adjusting any analytical financial stability framework.

Figure A.5

The coverage of the ECB’s FSR has changed since 2004 due to crises, changes in the financial system’s structure and new policy mandates

Changes in the structure and content of the ECB’s FSR since the first issue

(2004, 2024)

Source: ECB.

The analysis of textual data makes it possible to systematically measure sentiment in FSRs, supplying tentative evidence of early warning properties. Natural language processing techniques make it possible to measure the sentiment embedded in FSRs. The financial stability sentiment index based on Correa et al. compares the total number of words conveying positive and negative sentiment.[25] The index suggests that sentiment in FSRs across major advanced economies exhibits strong co-movement that is consistent with that exhibited by their financial and business cycles (Chart A.2, panel a). In addition, sentiment in FSRs tends to turn more negative around major crises such as the global financial crisis or the pandemic, indicating that the resilience of financial systems is being tested. Zooming in on the ECB’s FSR, findings from a statistical exercise show that the sentiment index contains some early warning properties around episodes of systemic stress, defined as bouts of coincident financial market and real economic stress (Chart A.2, panel b). As these systemic stress episodes have high economic costs, public discussion of financial system vulnerabilities offers value added to a range of stakeholders.

Chart A.2

Financial stability sentiment in the FSRs of major advanced economies has co-moved and appears to have early warning properties for systemic stress episodes

a) Financial stability sentiment of selected FSRs over time | b) Financial stability sentiment of the ECB’s FSR around euro area systemic stress events |

|---|---|

(Jan. 1998-June 2024, index) | (Q4 2004-Q2 2024; quarters, index) |

|  |

Sources: Bank of England, ECB, Federal Reserve, IMF and ECB calculations.

Notes: Panel a: financial stability sentiment is measured as the relative proportion of negative to positive words in financial stability reports, based on a dictionary developed by Correa et al.* The resulting sentiment index can vary between -1 and +1, with a value of +1 (-1) corresponding to the most negative (most positive) sentiment. UA stands for Ukraine. Panel b: the historical dispersion (median, 25th and 75th percentiles) of the financial stability sentiment is computed for a specific quarter across all available systemic stress episodes. Systemic stress is based on the peaks of the Composite Indicator of Systemic Stress (CISS) as determined by the Bry-Boschan algorithm. In line with the ECB/ESRB EU crises database set out in Lo Duca et al.**, only stress episodes in 2008, 2011 and 2020 were considered to be systemic. Quarterly averages are taken for the CISS, and the financial stability sentiment is interpolated to a quarterly frequency.

*) Correa, R., Garud, K., Londono-Yarce, J. and Mislang, N., “Constructing a Dictionary for Financial Stability”, IFDP Notes, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, 2017.

**) Lo Duca, M., Koban, A., Basten, M., Bengtsson, E., Klaus, B., Kusmierczyk, P., Lang, J., Detken, C. and Peltonen, T., “A new database for financial crises in European countries”, Occasional Paper Series, No 13, ESRB, July 2017.

FSRs have become more accessible over time, in terms of both length and language complexity. In a world in which information is abundant, there has been a clear trend towards making FSRs more impactful and reader friendly. One key development has been a reduction in page count (Chart A.3, panel a), which has helped communication become more succinct and better targeted. While in the early 2000s, FSRs often exceeded 200 pages, today they range between 70 and 130 pages. This variation in length is partly due to the different approaches central banks take to structure their communication. The ECB, for instance, publishes a review, offering a summary of developments since the publication of the previous issue, while other central banks produce reports, which tend to be more thematic in nature and can therefore be shorter. At the same time, the readability of these reports has improved, as signalled by the Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level score, which measures text complexity on the basis of sentence length and word complexity (Chart A.3, panel b). This reflects the adoption of layered communication techniques which make financial stability information easier to understand. Bucking this overall trend, the readability of FSRs tends to decline in times of crisis.

Chart A.3

The decline in page count and language complexity highlights the trend towards more accessible communication from central banks on financial stability

a) Total page count of financial stability reports of selected institutions over time | b) Language complexity of financial stability reports of selected institutions over time |

|---|---|

(1996-2024, average number of pages) | (1996-2024, score) |

|  |

Sources: Bank of England, ECB, Federal Reserve, IMF and ECB calculations.

Notes: Panel a: the total page count is an average across all editions in the given time period for each institution, Panel b: the complexity of the language employed is measured using the Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level score, which indicates how many years of formal training are required to understand the text based on sentence length and word complexity.

Social media helps amplify financial stability communication, with especially topical pieces having a longer-term impact. Alongside more formal outreach activities, social media has become an important channel for conveying key financial stability messages to the general public.[26] Findings from the ECB’s FSR are promoted via various platforms (X, LinkedIn and YouTube) as well as through podcasts and blogposts. While FSR-related social media activities only began in 2018, early evidence suggests that social media impressions have helped boost FSR readership (Chart A.4, panel a). Tracking readership numbers over time suggests that the FSR in general, and its topical content (boxes and special features) in particular, has a lasting impact, as its content is still read long after publication (Chart A.4, panel b). Topics related to climate change and technological innovation (e.g. crypto-assets and artificial intelligence) seem to have garnered particularly strong interest.

Chart A.4

Social media activity can help widen readership, while most analytical pieces in the ECB’s FSR have a longer-term impact

a) Number of social media impressions for FSR posts and FSR readership numbers one week after publication | b) Most-read special features of the ECB’s FSR one week and six months after publication |

|---|---|

(May 2018-May 2024, thousands) | (May 2019-May 2024, thousands) |

|  |

Sources: ECB, X, LinkedIn and ECB calculations.

Notes: Panel a: the size of the bubble represents the corresponding value of the financial stability sentiment index. The number of impressions comprises the sum of impressions from X (formerly Twitter) and LinkedIn. The red lines represent the averages. UA stands for Ukraine; SVB stands for Silicon Valley Bank.

5 Concluding remarks

Significant progress has been made on improving financial stability risk identification over the past two decades. Advances have been made in closing data gaps and the analytical toolkit has been expanded, leading to improved knowledge of how the financial system works. There is, however, no room for complacency. A key lesson from two decades of financial stability analysis is that frameworks need to be robust, agile and pre-emptive. This means that further work will be needed to better integrate cross-border vulnerabilities into systemic risk frameworks, as globalisation and technological innovations continue to blur traditional boundaries.

Central bank communication on financial stability and systemic risks has also evolved over the past two decades. An increasing number of central banks and other authorities have been communicating their views on sources of risk and vulnerabilities for reasons of crisis prevention as well as accountability. Publications on sources of risk and vulnerabilities remain the primary communication tool for financial system stability. However, the trade-off between transparency and stability remains a key challenge. Central banks must avoid overstating sources of risk, thereby inadvertently creating panic, but at the same time they should ensure they do not underplay vulnerabilities. A more tailored communication strategy, with content specifically designed for different audiences ranging from policymakers to the general public, can improve understanding and ensure that timely, appropriate action is taken. Increased use of digital platforms and social media will also be crucial in reaching a broader audience, although it is vital to maintain credibility and avoid oversimplification.

The authors gratefully acknowledge visualisation support by Mario Correddu, data support by Siria Angino and survey design support by Justus Meyer.

Article 127(5) of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union specifies that “the ESCB shall contribute to the smooth conduct of policies pursued by the competent authorities relating to the prudential supervision of credit institutions and the stability of the financial system.”

See, for instance, Gorton, G. and Winton, A., “Financial Intermediation”, in Constantinides, G.M., Harris, M. and Stulz, R.M. (eds.), Handbook of the Economics of Finance, Vol. 1, Part A, Elsevier, 2003, pp. 431-552.

Macroprudential policy tasks were conferred on the ECB in 2013 by Article 5 of the SSM Regulation. The aim is to contribute to the safety and soundness of individual credit institutions and the stability of the financial system, both at the euro area level and in each Member State.

The ECB has specific responsibilities in the area of lender of last resort, primarily governed by the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union and the ECB’s own statutes. In particular, the ECB may object to the provision of emergency liquidity assistance (ELA) by the national central banks of the euro area. These national central banks provide emergency funding to solvent banks facing temporary liquidity challenges. The ECB’s Governing Council monitors and can restrict or object to the provision of ELA by national central banks to ensure that it does not interfere with the ECB’s monetary policy.

See Schinasi, G., “Defining Financial Stability”, Working Papers, No 04/187, IMF, 2004.

Financial crises often have their roots in negative externalities and market failures. Such externalities can occur when the actions of individual financial institutions impose costs on others that are not reflected in market prices. For example, the failure of a major bank could lead to widespread economic disruption, affecting businesses and individuals who have had no direct dealings with the affected bank and resulting in a loss of confidence and weaker economic activity. In addition, typical market failures leading to financial crises include information asymmetry, moral hazard and coordination failures.

See Budnik, K. (ed.), “Advancements in stress-testing methodologies for financial stability applications”, Occasional Paper Series, No 348, ECB, May 2024.

See Constâncio, V. (ed.), “Macroprudential policy at the ECB: Institutional framework, strategy, analytical tools and policies”, Occasional Paper Series, No 227, ECB, July 2019.

See “Consolidation of the Financial Sector”, Group of Ten, 2001.

See De Bandt, O. and Hartmann, P., “Systemic risk: A survey”, Working Paper Series, No 35, ECB November 2000.

See Haldane, A., “Rethinking the Financial Network”, speech at the Financial Student Association, Amsterdam, April 2009; Gai, P., “The Robust-Yet-Fragile Nature of Financial Systems”, in Gai, P. (ed.), Systemic Risk: The Dynamics of Modern Financial Systems, Oxford University Press, 2013, pp. 8-27.

See Segoviano, M. and Goodhart, C., “Banking Stability Measures”, Working Papers, No 09/4, IMF, January 2009.

See also Fell, J. and Schinasi, G., “Assessing Financial Stability: Exploring the Boundaries of Analysis”, National Institute Economic Review, No 192, April 2005.

See Crockett, A., “Marrying the micro- and macro-prudential dimensions of financial stability”, BIS speech (Basel), 20-21 September 2000; De Bandt, O. and Hartmann, P., “Systemic risk: A survey”, Working Paper Series, No 35, ECB, November 2000; Fell, J. and Schinasi, G., “Assessing Financial Stability: Exploring the Boundaries of Analysis”, National Institute Economic Review, No 192, April, 2005; Schinasi, G., Safeguarding Financial Stability: Theory and Practice, International Monetary Fund, 2005; Goodhart, C.A.E., “A framework for assessing financial stability?”, Journal of Banking & Finance, 30(12), 2006, pp. 3415-3422; and Borio, C. and Drehmann, M., “Towards an operational framework for financial stability: ‘fuzzy’ measurement and its consequences”, Working Papers, No 284, BIS, June 2009.

See, for example, Powell, J.H., “The Federal Reserve’s Framework for Monitoring Financial Stability”, speech at The Economic Club of New York, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, New York, November 2018; and Adrian, T., Covitz, D. and Liang, N.J., “Financial Stability Monitoring”, Staff Reports, Federal Reserve Bank of New York, June 2014.

See Cukierman, A., “The Limits of Transparency”, Economic Notes, Vol. 38, Issue 1-2, 2009.

See also Haldane, A. and McMahon, M., “Central Bank Communications and the General Public”, AEA Papers and Proceedings, Vol. 108, 2018, pp. 578-83.

See Cihák, M., Muñoz, S., Sharifuddin, S.T. and Tintchev, K., “Financial Stability Reports: What Are They Good For?”, Working Papers, No 12/1, IMF, January 2012.

See Born, B., Ehrmann, M. and Fratzscher, M., “Central bank communication on financial stability”, Working Paper Series, No 1332, ECB, April 2011.

The ECB Knowledge and Attitudes survey is an annual, cross-sectional survey conducted among the general public in the euro area countries, which focuses exclusively on knowledge and perception of the ECB. Its results are not regularly published. For further information see “ECB Knowledge & Attitudes Survey 2021”, ECB, January 2022.

See the Financial Stability Review homepage on the ECB’s website.

In addition to euro area area-wide risk identification, the ECB also produces internal macroprudential policy reports and notes. These identify risks at a euro area country level and outline macroprudential policy options for addressing these risks. Macroprudential policy topics are also discussed in the ECB’s Macroprudential Bulletin.

The design and distribution of the survey risks introducing a selection bias, where certain readers may feel more compelled to respond than others. This means that the sample of respondents may not be fully representative of the entire readership of the FSR.

Correa, R., Garud, K., Londono-Yarce, J. and Mislang, N., “Constructing a Dictionary for Financial Stability”, IFDP Notes, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, 2017.

These outreach activities entail engagement with the media, international bodies and fora, market intelligence contacts and research institutes following the publication of each FSR.