Decrypting financial stability risks in crypto-asset markets

Published as part of the Financial Stability Review, May 2022.

The stellar growth, volatility and financial innovation currently seen in the crypto-asset ecosystem, as well as the rising involvement of institutional investors, show how important it is to gain a better understanding of the potential risks that crypto-assets could pose to financial stability if trends continue on this trajectory. Systemic risk increases in line with the level of interconnectedness between crypto-assets and the traditional financial sector, the use of leverage and lending activity. It is important to close regulatory and data gaps in the crypto-asset ecosystem to mitigate such systemic risks.

1 Introduction

Crypto-assets are currently the subject of intense policy debate. The different segments of crypto-asset markets include unbacked crypto-assets (such as Bitcoin), decentralised finance (DeFi) and stablecoins.[2] Crypto-assets lack intrinsic economic value or reference assets, while their frequent use as an instrument of speculation, their high volatility and energy consumption, and their use in financing illicit activities make crypto-assets highly risky instruments. This also raises concerns over money laundering, market integrity and consumer protection, and may have implications for financial stability.

Despite the risks, investor demand for crypto-assets has been increasing. This exuberance stems from, among other things, perceived opportunities for quick gains, the unique characteristics of crypto-assets (for instance programmability) compared with conventional asset classes, and the benefits perceived by institutional investors with regard to portfolio diversification. Major players in the payments industry have also stepped up their crypto-asset-based services, enabling easier retail access. While crypto-asset markets currently represent less than 1% of the global financial system in terms of size, they have grown significantly since the end of 2020. Despite recent declines, they remain similar in size to, for example, the securitised sub-prime mortgage markets that triggered the global financial crisis of 2007-08.

Risks to financial stability in the euro area stemming from crypto-assets were seen as limited in the past.[3] This special feature provides an update on crypto-asset market developments and a general overview of risks stemming from unbacked crypto-assets and DeFi, given the way in which they have evolved and their specific characteristics and risks. This article therefore abstracts from a specific discussion on risks and developments in stablecoins which, as shown by the recent TerraUSD crash and Tether de-peg, are not as stable as their name suggests and cannot guarantee their peg at all times.[4] Following a deep dive into crypto-asset leverage and crypto lending, we conclude that if the present trajectory of growth in the size and complexity of the crypto-asset ecosystem continues, and if financial institutions become increasingly involved with crypto-assets, then crypto-assets will pose a risk to financial stability.

2 Market developments in recent years

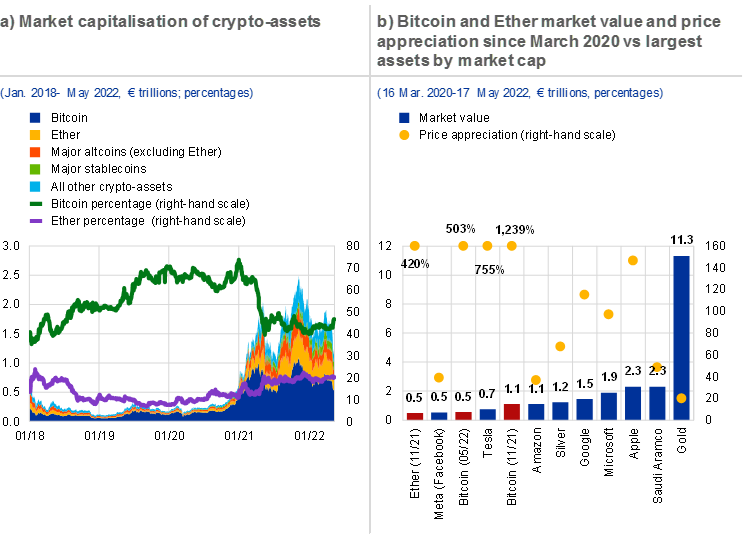

The crypto-asset universe has increased dramatically in both size and complexity since the end of 2020, expanding beyond Bitcoin. Despite recent market developments, the overall market capitalisation of the crypto-asset class is still around seven times bigger than it was at the start of 2020, having reached a high of over €2.5 trillion on aggregate in late 2021 (Chart B.1, panel a). Although the crypto-asset universe is still relatively small compared with the biggest stock exchanges (e.g. around 10% of STOXX Europe 600 market capitalisation), by November 2021 Bitcoin and Ether were among the largest assets globally (Chart B.1, panel b). Trading volumes for the most representative crypto-assets (including Bitcoin, Ether and Tether) have at times been comparable with or even surpassed those of the New York Stock Exchange or euro area sovereign bond quarterly trading volumes. There are now more than 16,000 crypto-assets in existence (ten new crypto-assets are launched every day on average), although only around 25 crypto-assets have a market capitalisation comparable with that of a large cap equity. At the same time, selected subsegments within the crypto-asset ecosystem such as stablecoins, non-fungible tokens (NFTs) and DeFi grew particularly strongly in 2021, indicating that the potential functionalities of crypto-assets are expanding.

However, crypto-asset markets also continue to be characterised by high levels of volatility. Over the last few years, the historical volatility of crypto-assets has continued to dwarf the volatility of the diversified European stock and bond markets. For example, while the volatility of the Bitcoin price has declined over the years, it is still significantly higher than for commodities such as silver and gold. Despite volatile movements and bouts of speculation (Chart B.1, panel a), crypto-assets trended upwards throughout most of 2021, leading to all-time-high prices for most individual crypto-assets. However, since early November the price of Bitcoin, as well as that of the other main unbacked crypto-assets, has more than halved amid a changing environment (US monetary tightening and increasing geopolitical tensions).

Chart B.1

The market value and complexity of the crypto-asset ecosystem has increased dramatically

Sources: Bloomberg Finance L.P., Crypto Compare and ECB calculations.

Notes: Crypto-asset market capitalisation is calculated as the product of circulating supply and the price of crypto-assets. If the circulating supply were adjusted for the lost bitcoins which are proxied by those that have not been used for longer than seven years, it would be around 20% lower. The selected major altcoins are Cardano (ADA), Bitcoin Cash (BCH), Dogecoin (DOGE), Link (LINK), Litecoin (LTC), Binance Coin (BNB), Ripple (XRP), Polkadot (DOT) and Solana (SOL). The selected major stablecoins are Gemini USD (GUSD), True USD (TUSD), USD Coin (USDC), Tether (USDT), Binance USD (BUSD) and Pax Dollar (USDP). Algorithmic stablecoins were excluded.

The increasing correlation of crypto-asset prices with mainstream risky financial assets during episodes of market stress casts doubt over their usefulness for portfolio diversification. There was an increase in the correlation between crypto-asset returns and stock returns during (and following) the market stress of March 2020, as well as during the December 2021 and May 2022 market sell-offs. This may suggest that, during periods of risk aversion across wider financial markets, the crypto-asset market has become more closely tied to traditional risk assets – a trend that may be due in part to the increased involvement of institutional investors.[5] Conversely, the correlation with gold has turned negative during a period of rising inflation expectations and geopolitical tensions.

Interconnectedness with the wider financial system has been growing. Linkages between crypto-assets and the euro area banking sector have been limited so far, although market contacts indicate there was growing interest in 2021, mainly via expanded portfolios or ancillary services associated with digital assets (including custody and trading services). Major payment networks have also stepped up their support of crypto-asset services, leveraging their retail networks and making crypto-assets more easily accessible to consumers and businesses. Some institutional investors (hedge funds, family offices, some non-financial firms and asset managers) are now also investing in Bitcoin and crypto-assets more generally.[6] In addition, market intelligence suggests that the growing involvement of asset managers is largely in response to demand from their own clients.

Demand from institutional investors in Europe has also risen. For example, 56% of European institutional investors surveyed by custody and execution services provider Fidelity Digital Assets[7] indicated that they have some level of exposure to digital assets – up from 45% in 2020 – with their intention to invest also trending upwards. One reason could be that measures taken by the public authorities may have been interpreted as endorsing crypto-assets, even though the latter remain largely unregulated. For example, since July 2021 German institutional investment funds have been allowed to invest up to 20% of their holdings in crypto-assets. This is further aided by the increasing availability of crypto-based derivatives and securities on regulated exchanges, such as futures, exchange-traded notes, exchange-traded funds and OTC-traded trusts, which have increased in popularity over the last few years in Europe and the United States. These products, together with clearing facilities, have made crypto-assets more accessible to investors as they can be traded on traditional stock exchanges, with the end user no longer having to deal with the complexities of custody and storage. However, the European crypto-asset management landscape is still relatively limited and is home to only 20% of total global crypto-assets funds in terms of primary office location.

Retail investors represent a significant part of the crypto-asset investor base. Recent results from the ECB’s Consumer Expectation Survey (CES)[8] for six large euro area countries[9] indicate, based on experimental questions, that as many as 10% of households may own crypto-assets (Chart B.2, panel a). Most crypto-asset owners reported holding less then €5,000 in crypto-assets, with a slight predominance of smaller holdings (below €1,000) in this group. At the other end of the spectrum, around 6% of crypto-asset owners confirmed that they held more than €30,000 in crypto-assets (Chart B.2, panel b). Looking at the income quintiles of the respondents, the pattern is largely U-shaped: the higher a household’s income, the more likely it is to hold crypto-assets, with lower-income households more likely to hold crypto than middle-income households (Chart B.2, panel c). On average, young adult males and highly educated respondents were more likely to invest in crypto-assets in the countries surveyed. With regard to financial literacy, respondents who scored either at the top level or the bottom level in terms of financial literacy scores were highly likely to hold crypto-assets.

Chart B.2

Surveys point to material household holdings of crypto-assets in large euro area countries

Source: ECB Consumer Expectation Survey (CES).

Notes: The CES conducted in November 2021 included some experimental questions concerning crypto-assets. Specifically, respondents, aged 18-70 years, were asked if they or anyone in their household owned financial assets in various categories including crypto-assets (e.g. “Bitcoin or other”). Respondents were also asked to estimate the total value of such assets. Other surveys exist that aim to gather information on retail holdings of crypto-assets. They may differ in terms of the scope of the questions asked or coverage, which may lead to higher or lower figures for crypto-asset ownership or crypto-asset related activities in the countries covered.

3 Risks stemming from crypto-assets

The relevant authorities have ascertained that crypto-assets pose risks from an investor protection and market integrity perspective.[10] The European supervisory authorities have recently reiterated their warning that crypto-assets are highly risky and speculative. Crypto-assets are not suitable for most retail investors (either as an investment or store of value, or as a means of payment) who could lose a large amount (or even all) of the money they have invested. Consumer protection risks include (i) misleading information, (ii) the absence of rights and protections such as complaints procedures or recourse mechanisms, (iii) product complexity with leverage sometimes embedded, (iv) fraud and malicious activities (money laundering, cyber crime, hacking and ransomware), and (v) market manipulation (lack of price transparency and low liquidity).

The significant volatility of crypto-assets in recent months has not resulted in contagion or any notable defaults by financial institutions, but the risks of these are increasing. Greater involvement of financial institutions could fuel the growth of crypto-assets still further and increase financial stability risks. Any principal-based crypto-asset exposures on the part of systemic institutions, especially if the assets involved are unbacked, could put capital at risk, with potential knock-on effects on investor confidence, lending and financial markets if the exposures are of a sufficient scale. Financial institutions themselves could face reputational risks as well as climate transition risks. Some international banks (including euro area banks) are already trading and clearing regulated crypto derivatives, even if they do not hold an underlying crypto-asset inventory. Market intelligence suggests that other EU banks and financial institutions are interested in offering custody, trading and market-making services once regulatory uncertainty diminishes with the entry into force of the Markets in Crypto-Assets (MiCA) Regulation. This will further increase interconnectedness.

If current growth and market integration trends persist, then crypto-assets will pose a risk to financial stability. Unbacked crypto-assets can have financial stability implications through four main transmission channels: wealth effects, confidence effects, financial sector exposures and the use of crypto-assets as a form of payment.[11] While all these channels are increasing in size and complexity, they lack internal shock absorbers that could provide liquidity at times of stress. For example, the wider involvement of financial institutions or the use of crypto-assets as a form of payment would increase the potential for spillover to the wider economy, particularly if leverage were employed.

Although EU regulation has been proposed to mitigate the risks posed by crypto-assets, agreement on this is yet to be reached. In the EU, the Commission’s proposal for the MiCA Regulation, first published in September 2020, has not yet been agreed by EU co-legislators. This means the Regulation will not be applied before 2024 at the earliest, as it is not expected to be applied until 18 months after it enters into force. Given the speed of crypto developments and the increasing risks, it is important to bring crypto-assets into the regulatory perimeter and under supervision as a matter of urgency. In addition, it will be important to review the sectoral regulations to ensure that any financial stability risks posed by crypto-assets, particularly those arising from their interconnectedness with traditional financial institutions, are mitigated.

Significant informational and data shortcomings persist, hindering the proper assessment of financial stability risks. These shortcomings include not only quantitative issues but also the reliability and consistency of data, and the fact that a significant proportion of activities take place outside the regulatory perimeter. Most publications from crypto-asset service providers (including platforms, exchanges and data aggregators) are not verifiable and should be treated with caution, while the limited regulatory data currently available (e.g. data for derivatives and alternative investment funds) offer only a partial (and potentially inaccurate) picture. As long as there continue to be no official statistics on crypto-assets or reporting of underlying data to a supervisory or oversight authority, the reliability of the metrics from the above sources and the full extent of possible contagion channels with the traditional financial system cannot be fully ascertained.[12] This is particularly relevant for the assessment of the risks stemming from the use of leverage or the reuse of collateral in crypto lending.

4 Assessing the role of leverage in crypto-asset markets

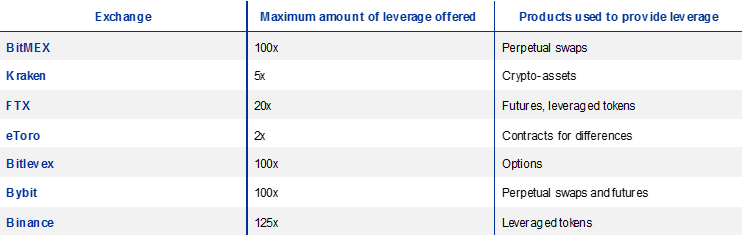

Financial stability risks could be amplified by the growing options offered by crypto exchanges for investors to increase their exposure through leverage. Products such as leveraged tokens,[13] futures contracts and options can allow investors to synthetically increase their exposure to crypto-asset returns (and risk). Some crypto exchanges offer ways to increase exposures by as much as 125 times the initial investment (Table B.1). However, the total volumes of leveraged contracts in crypto-asset markets and the extent to which leverage is actually used on these trading platforms are generally not reported. Furthermore, some investors use borrowed funds to purchase their exposure (margin trading), thus increasing the risks to financial stability.

Table B.1

Leverage amount offered by major crypto-asset exchanges

Source: Exchange websites.

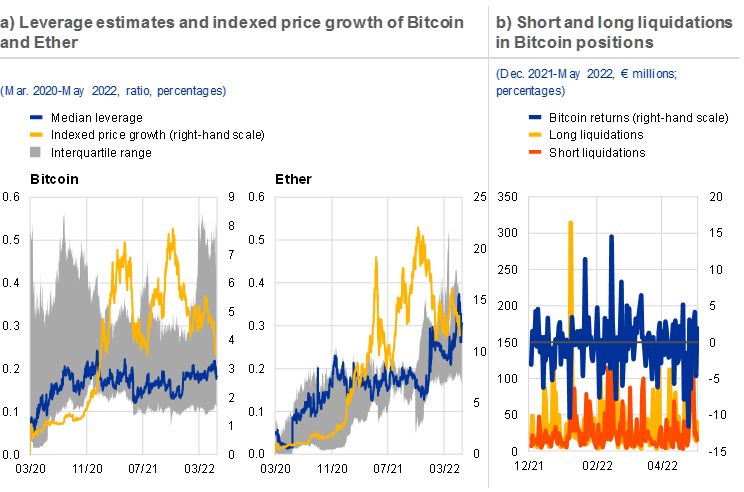

Estimates suggest there has been a slight increase in crypto-asset leverage in recent years.[14] Measures based on both Bitcoin and Ether futures indicate that aggregate leverage has been increasing since 2020 (Chart B.3, panel a), with a wider dispersion on individual exchanges for Bitcoin than for Ether. The rise in leverage in the Ethereum blockchain could be related to the growth of DeFi and associated activities where funds borrowed in one transaction can be reused as collateral in others. Even if leverage is currently limited at an aggregate level for the main unbacked crypto-assets, any concentration of high leverage in a few key market participants could still prompt stress.

Another useful dimension to consider when analysing leverage in crypto-asset markets is the volume of long and short liquidations. In the face of adverse price movements in the underlying there can be significant spikes in the volume of liquidations, which could cause further price declines. Drops in Bitcoin prices have been exacerbated by the increasing liquidation volumes associated with long positions in Bitcoin futures (Chart B.3, panel b), as the several spikes in long liquidation volume follow an initial price drop and precede the dipping points in the return series. This provides confirmation that leverage is contributing to the volatility observed in crypto-asset markets.

Chart B.3

Increased use of leverage points to higher risk-taking

Sources: Glassnode, Laevitas and ECB calculations.

Notes: The estimated leverage ratio is calculated as (open interest of the exchange) / (reserve of the exchange). The following exchanges are covered for Bitcoin: Binance, Bitfinex, BitMEX, FTX, Huobi, Kraken and OKEx; and for Ether: Binance, Bitfinex, Huobi, Kraken and OKEx. The result shows how much leverage traders are using on average. A higher ratio indicates that more investors are taking higher leverage risks.

5 Crypto lending in the search for yield

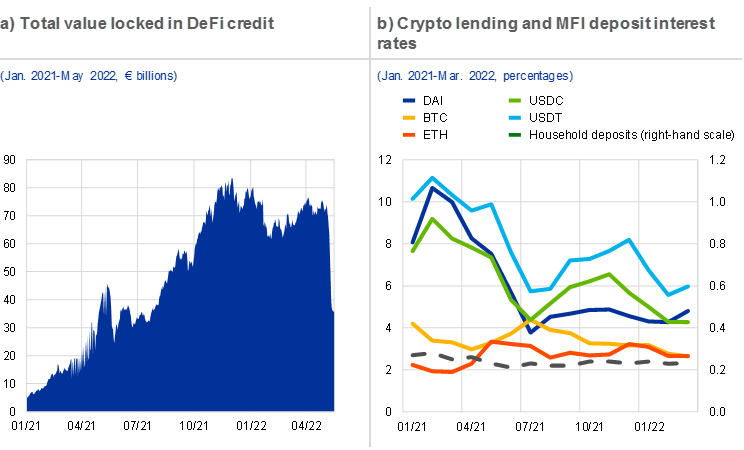

Although crypto lending[15] (borrowing fiat money or other crypto-assets by using crypto-assets as collateral) is still limited, it has grown considerably. Investors can earn interest on their digital asset holdings, usually at a higher rate than they can obtain from a bank (Chart B.4, panel b), by lending their assets out or borrowing against their digital asset holdings through overcollateralisation.[16] This crypto lending is offered by both centralised and decentralised service providers and usually takes place without any formal supervision or regulatory checks and balances, such as the need to provide a credit score. Loan-to-value (LTV) ratios, which are voluntarily set by the holders of the governance tokens of a DeFi application, are set quite low to mitigate risks (typically in the range of 25-50%) considering the high volatility of crypto. Crypto credit on DeFi platforms grew by a factor of 14 in 2021, while the total value locked[17] was hovering at around €70 billion (Chart B.4, panel a) until very recently, on a par with small domestic peripheral European banks. Crypto lending has spurred “yield farming” investment strategies such as incentivising investors to lend their crypto-assets to a pool that helps provide liquidity to DeFi systems, while offering potential investors the highest possible returns at all times. Currently, the crypto-asset deposit/lending industry is still quite small compared with traditional banking, although it could continue to grow rapidly.

Crypto lending may fall under existing financial regulation and has come under increased regulatory scrutiny. In the United States, the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) fined the centralised BlockFi service USD 100 million for failing to register the offers and sales of its retail crypto lending product as required under US securities law.[18] Previously, Coinbase dropped the launch of a new lending product following SEC warnings that it constituted an unregistered security. Although such cases are still unknown in the EU, these developments show that regulation is, in principle, technology-neutral. DeFi platforms that mimic traditional financial services would do well to ensure they comply with existing EU financial regulation before offering their services to EU clients to avoid the risk of any legal action.

Chart B.4

DeFi credit is currently small but is growing rapidly as investors search for yields above bank deposit rates

Sources: DefiLlama, Compound, DeFi Rate, ECB MFI MIR and ECB calculations.

Notes: Panel a: total value locked might be overestimated due to reuse of tokens. Panel b: crypto lending rates are calculated as the average of the 30-day average offered interest rate in 13 DeFi and CeFi (centralised) platforms. Not all platforms offer lending for all of the selected crypto-assets. Abbreviations are as follows: stablecoins: Tether (USDT), Dai (DAI) and USD Coin (USDC); unbacked crypto-assets: Bitcoin (BTC) and Ether (ETH). The deposit rate is the average interest rate offered by monetary financial institutions (MFIs) in the euro area to households and non-profit organisations.

Rehypothecation (where collateral for a loan can be re-pledged in order to obtain another loan)[19] increases the chances of a breach of LTV limits and could cause liquidity to vanish very quickly in the case of a big shock. The high volatility of crypto-assets means that LTV limits may be exceeded in a market downturn and that more collateral needs to be posted by borrowers, who could potentially lose that collateral. In addition, if borrowers are not able to pay back their loans, investors may seek to withdraw their funds in a panic, potentially leading to an investor run. The likelihood of such a run could be exacerbated by the high degree of concentration in liquidity provision in decentralised protocols. As they are outside the regulatory perimeter, there is no guarantee in such instances that investors would get their money back (or borrowers their collateral) as they would in the case of a bank deposit, given the existence of deposit guarantee schemes. This reflects the lack, in many cases, of investor protection regulation, the highly technical and fast-moving nature of the market segment, and the use of different tokens in terms of assets purchased, collateral posted or interest paid. Although the risks are currently small, they could rise significantly if platforms started to offer services to the real economy, instead of remaining confined to the crypto universe. In such a scenario, a decline in value of the collateral could lead to margin calls, borrower/lender defaults and reduced borrowing, potentially affecting economic activity (particularly if crypto-assets were used as collateral for consumer and business loans).

6 Conclusions

The nature and scale of crypto-asset markets are evolving rapidly, and if current trends continue, crypto-assets will pose risks to financial stability. While interconnectedness between unbacked crypto-assets and the traditional financial sector has grown considerably, interconnections and other contagion channels have so far remained sufficiently small. Investors have been able to handle the €1.3 trillion fall in the market capitalisation of unbacked crypto-assets since November 2021 without any financial stability risks being incurred. However, at this rate, a point will be reached where unbacked crypto-assets represent a risk to financial stability.

Systemic risk increases in line with the level of interconnectedness between the financial sector and the crypto-asset market, the use of leverage and lending activity. Based on the developments observed to date, crypto-asset markets currently show all the signs of an emerging financial stability risk. It is therefore key for regulators and supervisors to monitor developments attentively and close regulatory gaps or arbitrage possibilities. As this is a global market and therefore a global issue, global coordination of regulatory measures is necessary.

It is important to close regulatory and data gaps in the crypto-asset ecosystem. In the EU, the MiCA Regulation should be approved by the co-legislators as a matter of urgency to ensure it is applied sooner rather than later. However, MiCA is only a first step. The sectoral regulations will need to be reviewed to ensure financial stability risks posed by crypto-assets are mitigated. Any further steps that allow the traditional financial sector to increase its interconnectedness with the crypto-asset market space should be carefully weighed up, and priority should be given to avoiding financial stability risks. This holds in particular when considering interconnections with parts of the financial system that are strictly regulated and benefit from a public safety net. Data gaps should be closed. The challenges faced in monitoring financial stability risks from crypto-assets developments and interconnectedness with the traditional financial sector will persist as long as there are no standardised reporting or disclosure requirements.[20]

The authors are grateful to France Marie Alix De Pradier d’Agrain, Lorenzo Pangallo and Antonella Pellicani for data support.

See the definitions used in “Crypto-assets and Global ‘Stablecoins'”, Financial Stability Board, last updated February 2022.

For previous assessments, see the box entitled “Financial stability implications of crypto-assets”, Financial Stability Review, ECB, May 2018.

For a discussion on the risks of the third segment of crypto-asset markets (stablecoins) and their interconnectedness with the general crypto-asset ecosystem and the traditional financial sector, see, for example, the article entitled “The expanding functions and uses of stablecoins”, Financial Stability Review, ECB, November 2021; and the article entitled “A regulatory and financial stability perspective on global stablecoins”, Macroprudential Bulletin, No 10, ECB, May 2020.

See also Tara, I., “Cryptic Connections: Spillovers between Crypto and Equity Markets”, Global Financial Stability Notes, No 2022/01, IMF, January 2022; and Szalay, E., “Bitcoin’s weekend tumble hints at Wall Street traders’ growing sway”, Financial Times, December 2021.

See Fletcher, L., “Hedge funds expect to hold 7% of assets in crypto within five years”, Financial Times, June 2021. A recent survey of 100 hedge fund CFOs by fund administrator Intertrust Group found that they expected to allocate, on average, 7.2% of their assets to crypto-assets by 2026. A Goldman Sachs survey carried out in 2021 showed that 15% of family offices have exposures to crypto-assets, while nearly half of all family offices are interested in taking on exposures.

See “Institutional Investor Digital Assets”, Fidelity Digital Assets, 2021.

The CES collects high-frequency information on the perceptions and expectations of households in the euro area, as well as on households’ economic and financial behaviour.

Belgium, Germany, Spain, France, Italy and the Netherlands.

See the warning issued by the EU financial regulators on 17 March 2022.

See the updated “Assessment of Risks to Financial Stability from Crypto-assets”, Financial Stability Board, February 2022; and Chapter 2 entitled “The Crypto Ecosystem and Financial Stability Challenges”, Global Financial Stability Report, IMF, October 2021.

Some issues with measuring crypto-asset phenomena using “classic metrics” have been described in the article entitled “Understanding the crypto-asset phenomenon, its risks and measurement issues”, Economic Bulletin, Issue 5, ECB, 2019.

Leveraged tokens allow their holder to take a leveraged position on a crypto derivative (e.g. a perpetual future on BTC).

One popular indicator used to estimate crypto-asset leverage is calculated as the open interest of derivatives on a specific crypto-asset relative to the amount of crypto-assets held in reserve by the exchanges offering those derivatives. The open interest conveys a measure of the total (crypto) assets, while the reserves held by exchanges may be seen as the equity. In this way, the ratio used to measure leverage in crypto-assets recalls the standard leverage ratio: assets over equity.

See also the definition given in Table 1 of the updated “Assessment of Risks to Financial Stability from Crypto-assets”, Financial Stability Board, February 2022: “By using smart contracts, users can become lenders or borrowers on DeFi platforms. Users typically post crypto-assets as collateral and then can borrow other crypto-assets”.

Although it seems rather counterintuitive, users facing unforeseen funding needs may prefer not to sell their holdings, as they expect the crypto-asset to increase in value in the future. Another advantage of borrowing is potentially avoiding or delaying the payment of capital gains taxes. Lastly, individuals can use funds borrowed via such platforms to increase their leverage on certain trading positions.

Total value locked represents the sum of all assets deposited in DeFi protocols earning rewards, interest, new coins and tokens, fixed income, etc.

See the press release entitled “BlockFi Agrees to Pay $100 Million in Penalties and Pursue Registration of its Crypto Lending Product”, US Securities and Exchange Commission, 14 February 2022.

As an example, borrowers can pledge crypto to obtain a stablecoin loan. This loan can be used as collateral in another liquidity pool in exchange for liquidity pool tokens, which are, in effect, a form of derivative. The liquidity pool tokens can be pledged in yet another liquidity pool to obtain another stablecoin loan, and so on.

The Financial Stability Board’s 2022 Data Gaps Initiative envisages the development of prospective data collections for crypto-assets. Some statistical initiatives are also geared towards the appropriate treatment and possible identification of crypto-asset activities and players.