TLTRO III and bank lending conditions

Published as part of the ECB Economic Bulletin, Issue 6/2021.

1 Introduction

Targeted longer-term refinancing operations (TLTROs) play a key role in preserving favourable bank financing conditions for households and firms, thereby contributing to inflation reaching the ECB’s target of 2% in the medium term. The operations are part of a broad set of complementary policy instruments, which include asset purchases, negative interest rates and forward guidance.[1] Since their inception in 2014, TLTROs have supported the transmission of monetary policy by incentivising lending through their targeting feature and by providing a reduction in bank funding cost, which has been instrumental in avoiding a deterioration in lending conditions that would have otherwise occurred. The third series of the TLTROs (TLTRO III) was introduced in early 2019. The initial announcement of TLTRO III in March 2019 reassured markets about the extension of the pre-existing TLTRO II. The operations were intended to stave off “congestion effects” in bank funding markets that would have otherwise materialised because of the need to replace expiring TLTRO II funds. The operations were recalibrated in September 2019 to preserve favourable bank lending conditions, ensure the smooth functioning of the monetary policy transmission mechanism and therefore further support the accommodative stance of monetary policy. From the start of the coronavirus (COVID-19) crisis, the recalibration of this tool was, thanks to its design and the role of the euro area banking system in the monetary policy transmission mechanism, an integral part of the ECB’s policy response to ensure favourable borrowing conditions for firms and households during the pandemic.

TLTRO III provided ample liquidity at attractive rates to address the emergency liquidity needs of households and firms induced by the pandemic. The ECB’s monetary policy response to the COVID-19 crisis involved two main tools. First, asset purchases supported favourable financing conditions for the real economy in times of heightened uncertainty, both through an additional envelope under the regular asset purchase programme (APP) and via the launch of the pandemic emergency purchase programme (PEPP). Second, the recalibration of the existing TLTRO III operations helped banks secure funding at favourable terms to support access to credit for firms and households.[2] The Governing Council’s decisions of 12 March[3] and 30 April[4] 2020 have secured the transmission of monetary policy via banks at times of elevated uncertainty and high liquidity needs by expanding banks’ borrowing allowance under TLTRO III from 30% to 50% of the eligible loan book (providing an additional leeway of approximately €1.2 trillion) and reducing the interest rate applied on these operations to a rate as low as -1% until June 2021 for banks fulfilling the lending requirements. These decisions also enlarged the set of assets eligible to collateralise the borrowing under TLTRO III and enhanced banks’ flexibility of repayment options and participation modalities across operations. The Governing Council’s decisions of 10 December 2020[5] further widened the borrowing allowance to 55% and prolonged the period in which banks could secure a rate as low as -1% to June 2022, subject to additional lending requirements until the end of 2021. This served to shelter borrowing conditions from the ripple effects of the pandemic.

The magnitude of the pandemic shock, the broad-based policy response and the attractive design of TLTROs (after the various recalibrations) resulted in one of the largest liquidity injections by the ECB directly into the euro area banking sector, bringing the total uptake to €2.2 trillion as of June 2021, thereby providing substantial support to the euro area throughout the entire pandemic period. The monetary policy response to buffer the impact of the pandemic on borrowing was complemented by policy support from other policy domains, ranging from microprudential and macroprudential policy via capital relief measures, to fiscal policy via extensive use of government guarantees and moratoria. The favourability of TLTRO conditions, together with the broadened eligibility of assets that could be pledged as collateral (see Box 1), the capital space and loan demand reinforced by other policies, enabled euro area banks to participate widely in the TLTRO III programme, leading to the largest participation in Eurosystem refinancing operations so far. The overall take-up exceeded €1.5 trillion after the June 2020 operation and subsequent operations brought it up to €2.2 trillion as of June 2021 (Chart 1). This article studies how, and by how much, this targeted longer-term central bank funding has affected bank lending conditions.

Chart 1

Borrowing from the Eurosystem

(EUR billions)

Sources: ECB and ECB calculations.

Notes: The chart shows developments in borrowing from the Eurosystem broken down into the different lending facilities. “MROs” are main refinancing operations. “LTROs (orig. maturity < 3y)” are longer-term refinancing operations with original maturity below three years. “3y LTROs” are longer-term refinancing operations with a three-year original maturity. “TLTRO I”, “TLTRO II” and “TLTRO III” refer to the three programmes of targeted longer-term refinancing operations. “PELTROs” are pandemic emergency longer-term refinancing operations. “2020 bridge LTROs” are longer-term refinancing operations introduced to bridge liquidity needs between the announcement of the TLTRO recalibration in March 2020 and the first subsequent operation in June 2020.

This article is organised as follows. Box 1 sheds light on the role of the collateral easing measures. Section 2 explains how the stimulus from TLTRO III is transmitted via banks to the final borrowers. Box 2 focuses on the programme’s impact on money market rates. Section 3 documents the extent to which TLTRO III has eased bank lending conditions, considering its efficiency vis-à-vis other policy measures and the scope for potential side effects. Box 3 discusses the impact of TLTRO III on excess liquidity. Section 4 provides this article’s overall conclusions.

Box 1

TLTRO III and collateral easing measures

Collateral easing measures constitute a core element of the ECB’s monetary policy response to the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic. Since the provision of Eurosystem liquidity is based on eligible collateral, the TLTRO III recalibrations were also accompanied by a comprehensive set of temporary measures aimed at preserving collateral availability by easing certain collateral standards (Figure A).[6] This box assesses the extent to which collateral easing measures have contributed to the large participation in TLTRO III operations. It also examines how these have further created a supportive environment for banks to lend to the real economy. The analysis covers the period between 5 March 2020 and 24 June 2021 (also referred to as the analysed period).

Figure A

Collateral easing measures in response to the coronavirus pandemic

Notes: “ACC” refers to additional credit claims, “ABS” refers to asset backed securities and “CQS” refers to credit quality step as defined in the Eurosystem Credit Assessment Framework.

The large recourse to TLTRO III was supported by a sizeable expansion of mobilised Eurosystem collateral. In anticipation of an increase in their TLTRO III borrowing capacity as of June 2020, and following the implementation of the collateral easing measures, the total collateral value after haircuts pledged by participating banks has significantly increased. This increase, owing to additional collateral mobilisation as well as the reduction in valuation haircuts, is notably observed in (additional) credit claims, covered bonds, and government bonds. At the end of the analysed period, the value of mobilised collateral by participating banks amounted to €2.6 trillion and was €1.3 trillion higher than pre-pandemic levels (+92%). This increase mirrors the parallel TLTRO net take-up of €1.6 trillion (see panel (a) of Chart A).

Collateral easing measures have contributed around 20% to participating banks’ increase in collateral positions. ECB estimates indicate that the total value of participating banks’ collateral attributable to the temporary easing measures amounts to €240 billion.[7] The largest part of this stemmed from the credit claims collateral category (€180 billion), which was mainly achieved by expanding additional credit claim (ACC) frameworks[8], notably accepting loans covered by public guarantee schemes issued in response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

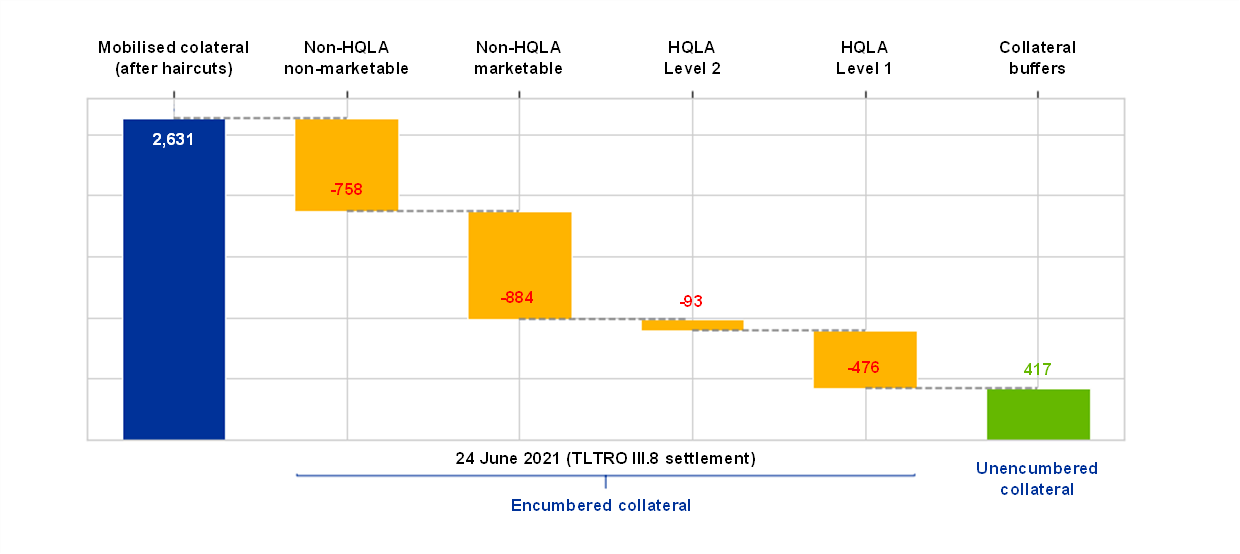

The expanded possibility of securing TLTRO III funding with collateral that does not qualify as high-quality liquid assets (HQLA) allowed banks to avoid a procyclical retention of liquidity in the face of the generalised liquidity shock that the economy was facing. Participating banks had the means to source market funding using HQLA as collateral and to improve, or at least preserve, their liquidity coverage ratio (LCR) by choosing to collateralise the TLTRO borrowing with non-HQLA. ECB estimates suggest that, at the end of the analysed period, encumbered non-HQLA collateral stood at €1.6 trillion or 74% of participating banks’ total central bank funding (panel (b) of Chart A). This translates to an overall increase in the encumbrance of non-HQLA collateral of €1.1 trillion over the analysed period. The encumbrance of large amounts of non-HQLA was facilitated by the pandemic-related eligibility expansion of (additional) credit claims and more incentivised use of non-HQLA through haircut easing.

Chart A

Mobilisation of Eurosystem collateral and recourse to Eurosystem credit operations by TLTRO III participants since the pandemic outbreak

a) Recourse to credit operations and collateral mobilisation

(EUR billions)

b) Collateral encumbrance

(EUR billions)

Source: ECB calculations.

Notes: The bar chart in panel (a) shows the mobilisation of Eurosystem collateral by asset category. The first observation of the bar chart (pre-pandemic outbreak collateral composition) refers to 5 March 2020. The area chart in panel (a) shows mobilisation of collateral by Eurosystem credit operations and collateral buffers (over-collateralisation). Data relate to TLTRO III participating banks up to the June 2021 TLTRO. For panel (b), collateral encumbrance is based on Article 7(2)(a) of Commission Delegated Regulation (EU) 2015/61 of 10 October 2014 to supplement Regulation (EU) No 575/2013 of the European Parliament and the Council with regard to liquidity coverage requirement for Credit Institutions Text with EEA relevance (OJ L 11, 17.1.2015, p. 1), i.e. it assumes that mobilised assets are encumbered in order of increasing liquidity, starting with non-HQLA. The ECB methodology for classifying assets mobilised with the Eurosystem into the relevant LCR liquidity categories (Level 1, Level 2A, Level 2B, non-HQLA) is mainly based on information contained in the ECB’s eligible assets database and is similar to the one described in Grandia, R., Hänling, P., Lo Russo, M. and Åberg, P. (eds.), “Availability of high-quality liquid assets and monetary policy operations: an analysis for the euro area”, Occasional Paper Series, No 218, ECB, Frankfurt am Main, February 2019. Encumbrance is calculated at bank level and aggregated up for all TLTRO III participants. Level 2A and Level 2B collateral are displayed aggregated (HQLA Level 2) and non-HQLA category is further broken down by non-HQLA non-marketable and non-HQLA marketable, with the additional assumption that non-HQLA non-marketable are encumbered first.

2 The transmission of TLTRO III to borrowers via banks

The transmission of TLTRO III to bank lending conditions operates through a variety of channels. TLTROs target bank lending to non-financial corporations and to households for purposes other than housing. The operations also provide a reduction in the funding cost of euro area banks, which activates a bank lending channel that can lead to lower lending rates and higher lending volumes. Moreover, as detailed below, additional channels complement the transmission of TLTROs, stimulating lending and supporting a decrease in borrowing costs for firms and households.

The incentive scheme embedded in the TLTROs stimulates bank lending to specific sectors, leading to increased competition in lending markets. In contrast with standard non-targeted operations, TLTRO III offers more advantageous pricing on borrowed funds; this pricing is conditional on participants achieving lending targets. This increases participants’ propensity to lend, especially in situations where uncertainty leads to a risk of tightening in access to funding for banks, which would normally induce them to tighten credit standards. As participants aim to lend more, competitive pressures in lending markets increase, which also induces non-participants to ease lending criteria to protect their market share.[9] The increase in competition is also one of the reasons why lending targets are carefully calibrated based on lending volume projections. Too high a bar to clear in order to achieve favourable TLTRO pricing could induce disproportionally competitive behaviour and potentially encourage excessive risk-taking. At the same time, setting a lending target that is too demanding could discourage some banks from participating and consequently reduce the effectiveness of the programme. At the same time, an insufficiently ambitious lending benchmark would compromise the effectiveness of the targeting feature of the operations.

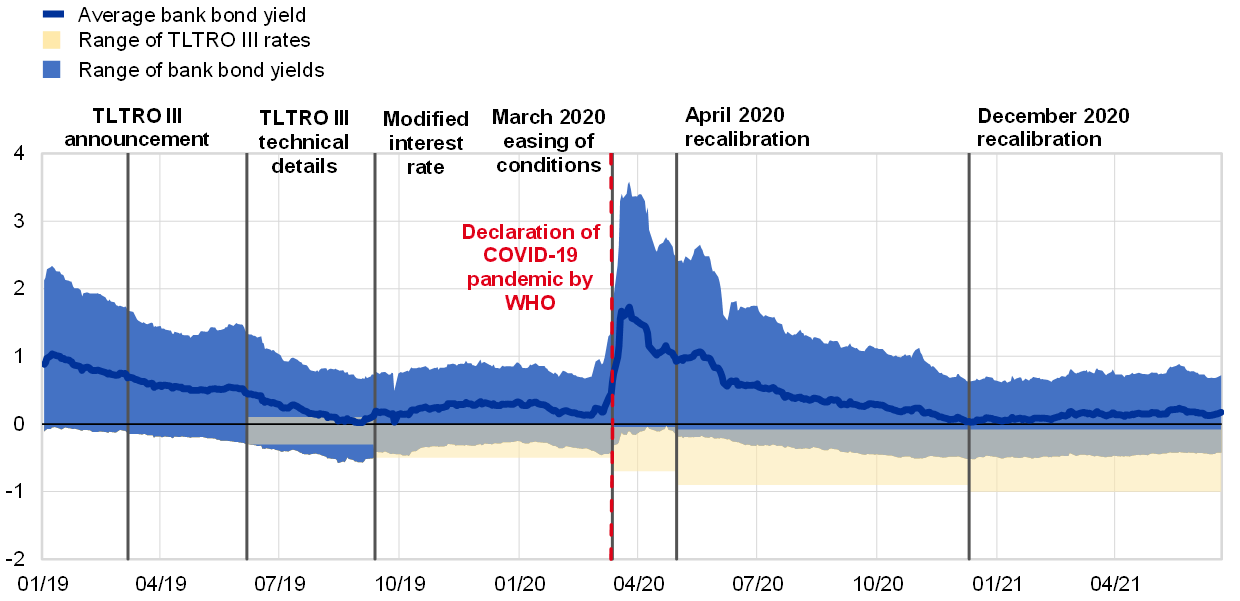

TLTROs provide both direct and indirect reductions in the cost of funding of euro area banks. Bank funding costs have moderated following TLTRO announcements (see Chart 2). TLTROs compress banks’ funding costs by offering long-term borrowing from the central bank at attractive rates. This can be used to replace more expensive sources of market funding. The resulting compression in the cost of funding of banks has a direct and an indirect component. For each participating bank, the direct cost reduction stems from the substitution of more expensive funds. For banks not directly participating in the programme, the reduction in the cost of funding is indirect and originates from a positive externality: since banks participating in TLTROs are likely to cancel or postpone their bond issuance, the resulting decrease in bond supply generates a reduction in the external funding cost even for those banks that do not directly borrow under the operations. Since banks operate in a competitive market, this leads to lower lending rates and increased credit volumes, as borne out by experience of previous TLTROs.[10] For this indirect channel to become active, participation in the programme at the aggregate level must be large, suggesting there is scope for important non-linearities to come into play, especially after the large take-up in the June 2020 operation. In this regard, the collateral policy of the Eurosystem and the decision to increase the borrowing allowance are key to enabling a large and broad-based participation, as discussed in Box 1.

Chart 2

Bank bond yields since 2019

(percentages per annum)

Sources: ECB, iBoxx, Centralised Securities Database (CSDB) and ECB calculations.

Notes: The chart displays the weighted average (dark blue line) and the p10-p90 range of euro area bank bond yields (shaded blue area). The TLTRO III range reflects the changes in the pricing introduced by each subsequent recalibration. The maximum TLTRO III rate reflects the highest possible rate achievable by keeping the funds until maturity. The minimum TLTRO III rate after the March 2020 and April 2020 recalibrations is the lowest possible rate achievable by repaying the funds at the earliest possible date, while after December 2020 it is the lowest possible rate achievable by repaying the funds at the end of the extended period of temporary rate reduction in June 2022.

TLTROs ultimately support borrowing conditions faced by households and firms by mitigating potential increases in lending rates and by providing a substantial compression in the cost of bank funding. TLTROs are normally transmitted to interest rates via their aggregate effects on the loan market. This is due to aggregate loan supply expanding enough to exert downward pressure on lending rates, which eventually decrease if loan demand is not strong enough. The recent experience with TLTROs after March 2020, when the demand for loans registered unprecedented levels, indicates the heightened relevance of at least two additional mechanisms of propagation are specific to the pandemic. First, the availability of TLTRO funds contributed to mitigating a potential increase in lending rates due to the surge in credit risk in the context of the economic disruptions brought forth by the pandemic. Second, the sharp and large increase in uncertainty about the macroeconomic outlook induced strong precautionary behaviour on the part of firms and households, which contributed to a large increase in deposit volumes. Given the relative difficulty in imposing negative rates on retail deposits, the reduction in bank funding cost provided by TLTROs contributes to preserving the smooth transmission of monetary policy by enabling banks to lower lending rates while preserving lending margins and avoiding excessive credit risk-taking.

By reducing liquidity constraints, TLTROs mitigate procyclicality that is driven by medium-term to long-term financing conditions. Since TLTROs have a longer maturity than standard refinancing operations, they contribute to easing regulatory constraints related to liquidity requirements, especially when the operations are initially implemented and their residual maturity is considerable. This allows banks to structure their liquidity composition in a less procyclical manner, issuing longer-term bonds when they are not overly expensive due to the transitory financial distress brought forth by the crisis to which the TLTROs are a response.

In addition, TLTROs inject central bank liquidity into the financial system, putting downward pressure on money market rates. TLTROs stimulate demand for central bank funding and effectively increase the quantity of excess liquidity in the system. The more attractive the TLTRO terms, the more broad-based the participation and resulting distribution of excess liquidity in the system. This reduces reliance on interbank markets for short-term liquidity needs, and thus compresses short-term rates, as shown in Box 2.

TLTROs also offer a backstop against escalating funding stress because banks can increase their recourse to TLTROs if faced with adverse scenarios. Like standard Eurosystem refinancing operations, TLTROs are demand-driven and allow potential participants to use the facility when access to market-based funding sources becomes challenging. Hence, the current price constellation for bank funding conditions is likely to reflect the effect of this option, including with regard to future refinancing conditions for banks, compressing the risk premia on bond yields and contributing to preserving favourable financing conditions.

Finally, TLTROs operate as a powerful credit easing measure in conjunction with the other active monetary policy instruments. The negative interest rate policy reinforces the incentive for loan origination by lowering the returns on risk-free assets, and at the same time maintaining the availability of TLTRO funding at very low rates, while the two-tier system for excess reserve remuneration mitigates potential frictions associated with the downward rigidity of retail deposit rates. Forward guidance keeps the intermediate segments of the risk-free curve, used by banks to price loans, at low levels. This stimulates credit demand and is complemented by the long term of TLTRO funds which helps compress the term premium of bank funding. Purchases of government bonds lower the returns on alternative uses of TLTRO funds, which helps to convey TLTRO liquidity towards the targeted sector. Purchases of corporate bonds narrow corporate bond spreads, thereby providing a direct channel of transmission from monetary policy to the real economy and creating space on banks’ balance sheets for extending more loans to firms not directly exposed to the asset purchases, such as small and medium-sized enterprises, via the use of TLTRO funds.[11]

Box 2

TLTRO III and money market rates

Money markets are the starting point of the monetary policy transmission mechanism that passes interest rates on to other financial market segments, which affects financing conditions in the broader economy. While a significant amount of unsecured transactions shifted to the secured segment in recent years, unsecured rates still play a crucial role as benchmark rates. For example, three-month and six-month unsecured EURIBOR rates serve as references for interest rate swap markets and interest rate futures markets, and for banks’ lending rates to businesses and households. This implies that movements in these unsecured rates are transmitted widely and swiftly to other economic agents.

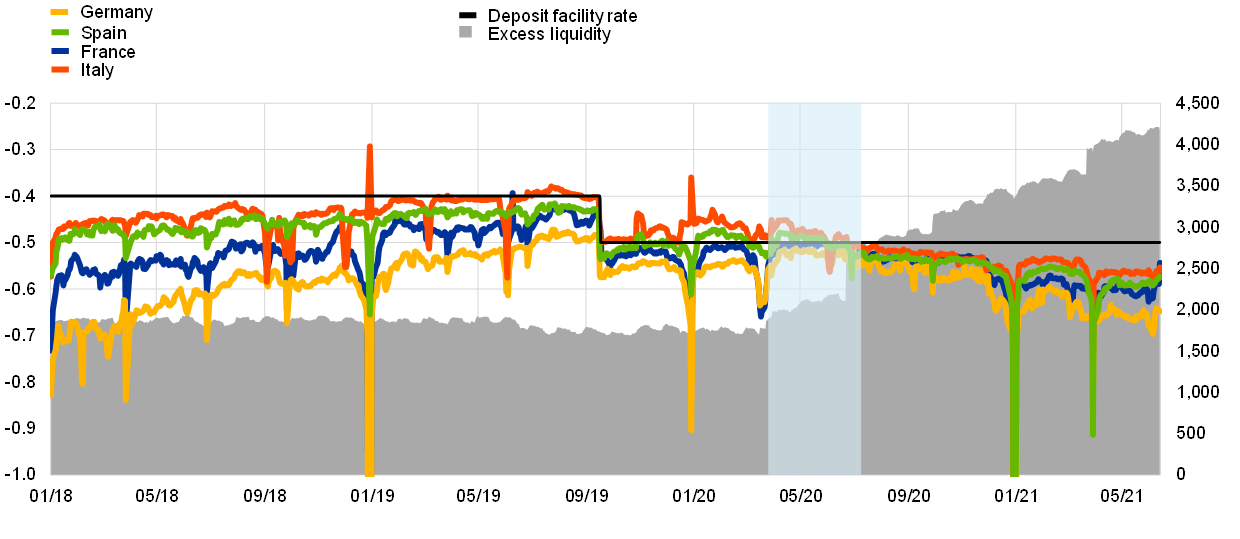

While the secured segment confirmed its resilience during the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic, the FX swap and unsecured term segments, including short-term securities issuance, were adversely affected. Interest rates and trading volumes of secured transactions remained broadly stable despite the increased risk aversion throughout spring 2020. In contrast, there was a sharp rise in unsecured term interest rates by more than 20 basis points, e.g. with regard to EURIBOR as well as rates for commercial papers. Furthermore, the cost of borrowing US dollars against the euro spiked in the FX swap market (see Chart A, where the blue area highlights the peak period of the COVID-19 crisis).

Chart A

Overview of rates in the euro money markets

a) Secured rates

(left-hand scale: percentages; right-hand scale: EUR billions)

b) Unsecured rates (STS, EURIBOR)

(left-hand scale: percentages; right-hand scale: EUR billions)

c) Foreign exchange rates EUR/USD (swap basis spread in percentage points)

(percentage points)

Sources: Panel (a) – ECB Money Market Statistical Reporting (MMSR); panel (b) – ECB MMSR, Bloomberg and ECB calculations; panel (c) – STS (Banque de France).

Notes: Panel (a) shows volume-weighted average rate per settlement date per collateral jurisdiction and only includes government collateral. The scale is limited to 1% for readability. Cut-off points: year-end 2019 for Germany (2.74%) and for France (2.13%); year-end 2020 for Germany (2.09%) and for France (1.57%) and for Spain (1.59%). Only trades with O/N, S/N and T/N maturities. The rate includes both borrowing and lending transactions. In panel (b) “STS” stands for short-term debt issuance based on NEU CP data. The blue area highlights the COVID-19 crisis period. In panel (c) the FX swap basis spread is calculated as the USD implied rate minus the USD OIS rate for the selected maturity. The axis is cut off at 300 basis points in the interests of readability. One-day trades combine the O/N, S/N and T/N for a selected settlement day.

To stabilise the stressed money market rates and ease funding conditions, the Eurosystem introduced several measures. The new and recalibrated lending operations for banks put significant downward pressure on unsecured term rates, driven by large excess liquidity and reduced need for banks to issue commercial paper. The inclusion of commercial papers issued by non-financial corporations in the purchases under the PEPP, the larger securities lending facilities offered by national central banks, and the broadening of collateral eligibility all supported the continuation of trades with corporate commercial paper and the supply of collateral to the market for repo transactions. Finally, the provision of US dollar liquidity at backstop prices via the swap line network of major central banks swiftly addressed distortions in the FX swap segment. The re-establishment of normal functioning of all money market segments over the second half of 2020 was evident in the normalisation in unsecured market rates.

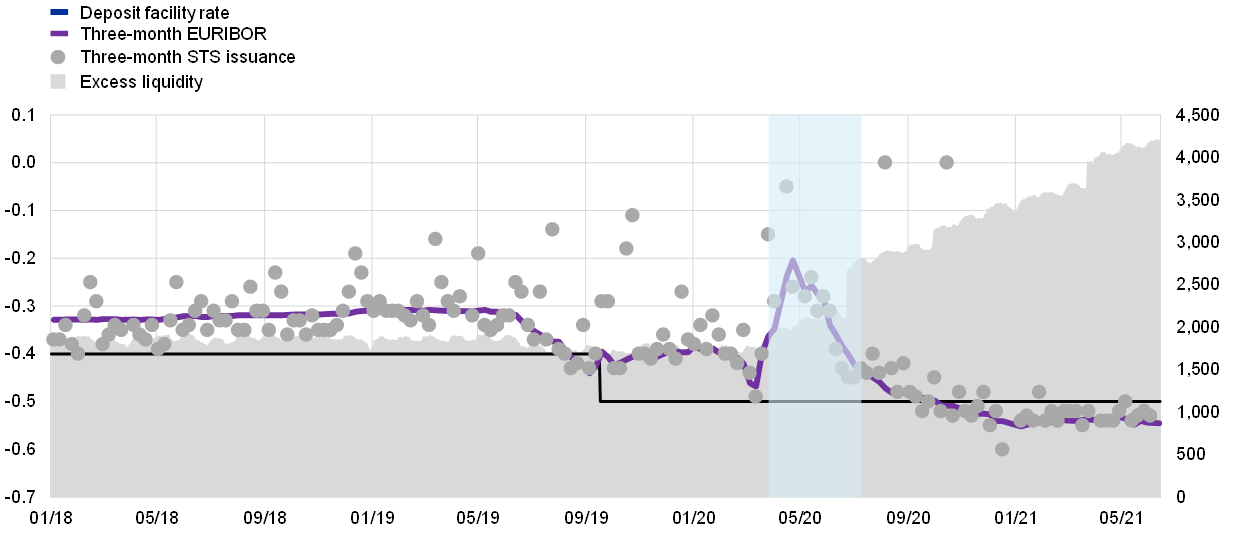

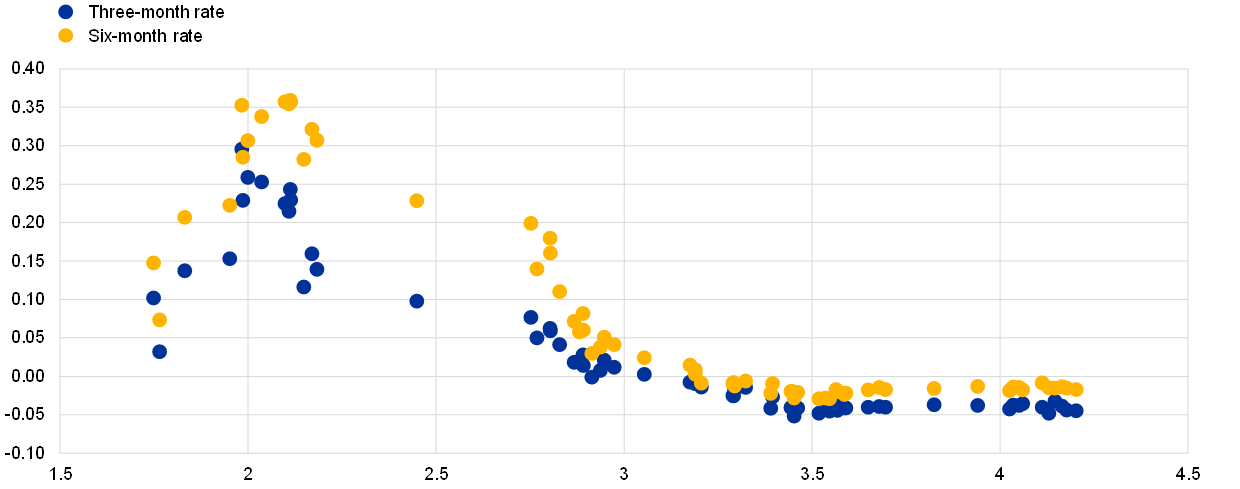

The recalibration of TLTRO III terms on two specific parameters was instrumental in achieving the desired easing effect on funding. Offering conditional funding below the deposit facility rate during two special lending periods, when the pandemic effects were most pronounced, provided a highly effective incentive that promoted high participation. Furthermore, the increase of the borrowing allowance permitted banks to increase their take-up from €0.3 trillion in March 2020 to €2.2 trillion in June 2021. This large injection of liquidity contributed to a decrease in the money market reference rates, such as three-month and six-month EURIBOR rates, which eased funding conditions for the broader economy via the money market channel (see Chart B).

Chart B

Relation between excess liquidity and unsecured term rates

(x-axis: excess liquidity in EUR trillions; y-axis: weekly average of EURIBOR spread to deposit facility rate in percentage points)

Sources: Bloomberg and ECB calculations.

Notes: Data cover the period from 12 March 2020 to 11 June 2021. R-squared for three-month rates: 77% and R-squared for six-month rates: 75%.

3 Impact on bank lending conditions

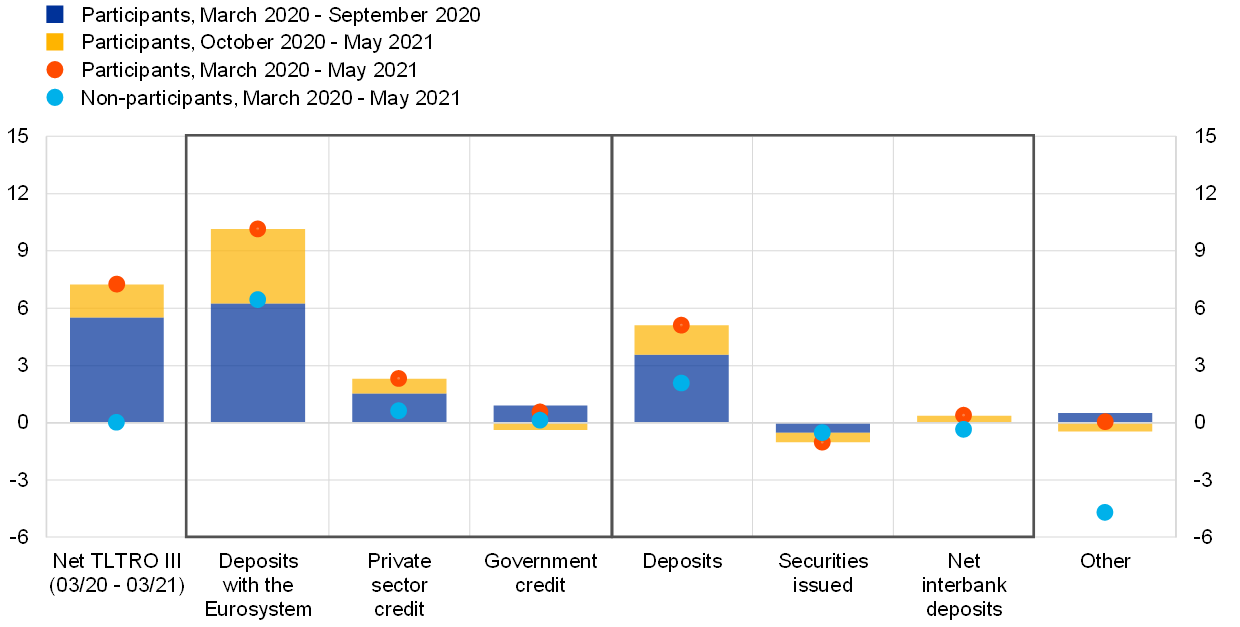

Evidence from bank balance sheet data

TLTRO III allowed banks to accommodate the large-scale increase in credit demand triggered by the pandemic. The growth in bank credit to the private sector has been substantial among TLTRO III participants since the start of the pandemic in the 13 months covered by the lending performance benchmark introduced in March 2020 (see panel (a) of Chart 3).[12] Loan growth has continued for participants in TLTRO III since the start of the additional lending performance evaluation period in October 2020[13], especially if compared with the figure for non-participants over the same period (see panel (b) of Chart 3). Together with an increase in the maturity of loans, which was also favoured by the availability of public guarantee schemes, this suggests that the operations helped banks to meet the increased credit demand in a sustainable way, allowing for a rotation from the initial emergency credit demand towards lending for longer-term purposes, including investment.[14] At the same time, acquisitions of government securities increased initially, reflecting increased issuance and liquidity demand by governments in order to finance the public support measures. Following this initial period, the net flows into government securities since October 2020 were negative, which is consistent with banks favouring origination of loans to the private sector over potential acquisition of government securities and also reflects the large absorption of these securities by asset purchases.

The temporary build-up of liquidity by individual TLTRO borrowers may also point to the credit expansion that these lenders may provide in the future. There has been a major increase in Eurosystem deposits since the start of the pandemic. This increase at the aggregate level is entirely mechanical, as the liquidity injected through the TLTROs (and the asset purchases that were conducted in parallel) circulates within the closed system of banks that have reserve accounts with the Eurosystem and is not reduced when banks expand credit to firms and households, which are not part of this closed system.[15] Moreover, the still sizeable build-up of liquidity deposited with the Eurosystem since the introduction of TLTRO III is the result of a range of factors, as discussed in Box 3.[16] At the bank level, it is important to note that euro area banks were actively engaged in meeting the urgent liquidity needs of the corporate and household sector. This supports the post-crisis recovery under challenging conditions in wholesale funding markets. At the onset of the crisis, banks responded to the emergency liquidity needs of firms by relying on their liquidity buffers. Considering the overall uncertainty and investor risk aversion, tapping markets to obtain the funds necessary to operate such a process could have generated strains in wholesale funding markets or outright rationing episodes. Individual banks have been accumulating on-balance sheet liquidity to be better able to buffer shocks as they have expanded lending. The reduction in money market rates observed after the June TLTRO III, and documented in Box 2, is a further signal that TLTRO funds are pivotal in applying the necessary downward pressure on the cost of the various funding options for banks. Currently, banks are still in the process of accompanying the exit from impairments in supply chains brought about by the pandemic shock, while also sheltering the corporate sectors from pockets of liquidity needs that isolated lockdowns might still entail as the vaccine roll-out normalises the functioning of the economy.

Chart 3

Evolution of balance sheet items for TLTRO III participants and non-participants

a) Developments in assets and liabilities

(percentage of main assets)

b) Volume of loans

(notional stock, February 2020 = 100)

Sources: ECB and ECB calculations.

Notes: Panel (a) shows the cumulated flows in the main assets and liabilities from March 2020 until September 2020 (blue bars) and from October 2020 until May 2021 (yellow bars) and from March 2020 until May 2021 (red dots) for participants in TLTRO III covered in the ECB’s individual balance sheet items dataset; developments for non-participants between March 2020 and May 2021 are displayed as light blue dots; data are rescaled by the size of the two groups, participants and non-participants, as measured by main assets at the end of February 2020. TLTROs are net from other funding from the Eurosystem as of March 2021 for the iBSI sample of banks (excluding micro-data groups to avoid double-counting and collapsed at the TLTRO participant level). On the asset side, private sector credit includes loans to non-financial corporations and households as well as holdings of private sector securities; government credit includes holdings of sovereign securities and credit to the government. On the liability side, deposits are vis-à-vis non-monetary financial institutions; (net) interbank funding is deposits minus loans from other monetary financial institutions, excluding the Eurosystem. Panel (b) displays the evolution of eligible loans for banks participating (blue line) and banks not participating (yellow line) in TLTRO III until May 2021.

Evidence from survey data

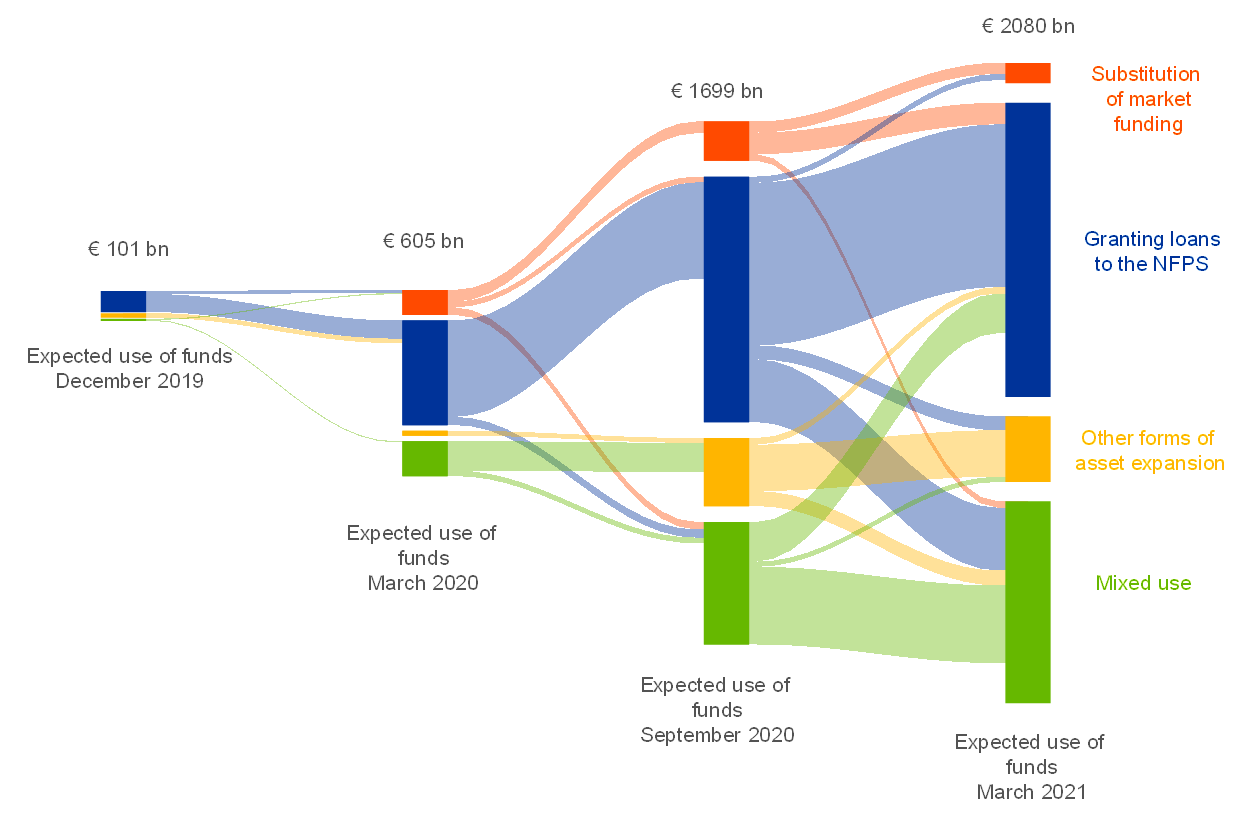

Soft information coming from surveys confirms that most banks participated in TLTRO III operations with the intention of using the funds for lending purposes. Hard data on bank balance sheets available up to March 2021 suggests that TLTRO funds have underpinned the ability of the euro area banking system to answer the initial unprecedented demand for liquidity coming from the non-financial private sector (NFPS) since the onset of the pandemic and to help with the rotation of firms’ exposures from emergency liquidity to term loans. On the one hand, the operations supported euro area banks’ ability and incentives to provide loans. On the other hand, developments in loan demand have played a crucial role. Soft information coming from surveys, such as the euro area bank lending survey, offers insight into the uses of these funds up to now and into the future. Comparing the responses over time also sheds some light on how the banking system reacted to the evolving features of TLTRO III.

The evolution of banks’ replies to the euro area bank lending survey illustrates how banks' intended uses of TLTRO funds adapted to the changing circumstances (Chart 4). Before the tensions associated with the COVID-19 pandemic, banks mainly expected to use TLTRO III funds either to grant loans to the NFPS or to roll over expiring funds from TLTRO II. As the pandemic crisis unfolded, some banks started to consider using TLTRO funds as a substitute for their market funding, although granting loans has remained the main expected destination of the additional liquidity. The TLTRO recalibration on 30 April 2020 has introduced stronger incentives to devote at least part of the funds to various forms of balance sheet expansion including, at least temporarily, holding deposits with the Eurosystem and purchasing government debt securities. At the same time, holding excess liquidity from TLTRO III participation was also motivated by banks’ precautionary attitudes amid unprecedented levels of uncertainty.[17] As lending to the private sector materialised, remaining TLTRO funds featured an increased role of mixed uses. In any case, banks’ expected uses of funds continue to suggest a high effectiveness of TLTROs in supporting lending conditions.

Chart 4

Evolution of expected use of TLTRO III funds

(share of respondents weighted by TLTRO III amounts)

Sources: ECB, euro area bank lending survey, and ECB calculations.

Notes: The four bars on the fourth column to the right measure the outstanding TLTRO III amounts in March 2021 distributed by the responses to the April 2021 euro area bank lending survey. The red bar measures the take-up of banks that reported that they will use TLTRO funds to substitute market funding sources. The blue bar measures the same take-up by banks that intend to use the funds for granting loans. The yellow bar collects take-up by banks that intend to use the funds for purposes other than substituting market funding or granting loans (government securities, holding as cash, financing other financial entities, etc.). The green bar reports the take-up by banks that do not plan to allocate the funds to a single category. The bars in the first column measure the outstanding TLTRO III amounts in December 2019, distributed by the responses to the January 2020 euro area bank lending survey. The bars in the second column measure the outstanding TLTRO III amounts in March 2020 and the amount of bridge LTROs distributed by the responses to the April 2020 euro area bank lending survey. The bars in the third column measure the outstanding TLTRO III amounts in September 2020 distributed by the responses to the October 2020 euro area bank lending survey. Shaded areas report take-up of banks that change their expected use of funds between survey waves.

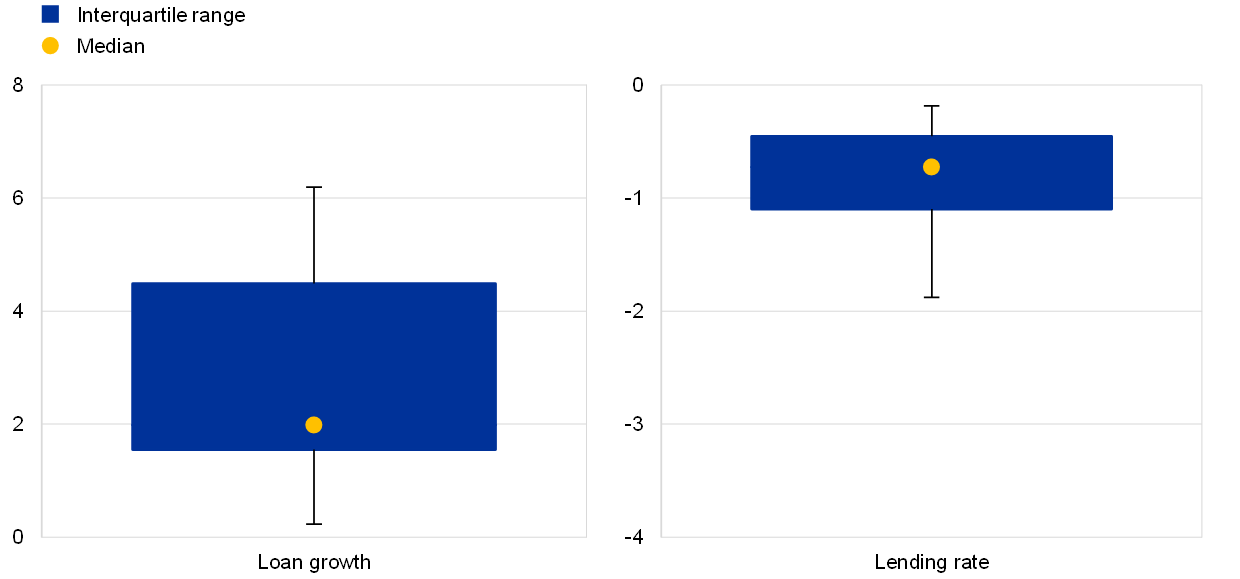

Estimated impacts of the TLTROs

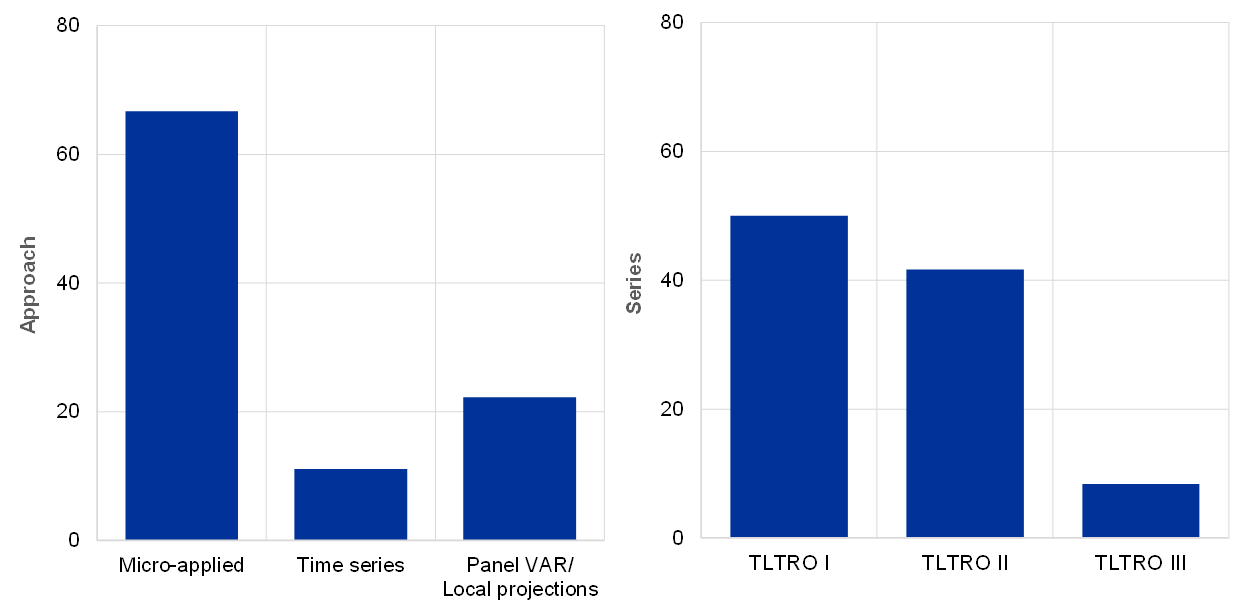

TLTRO III provides substantial support to bank lending conditions (Chart 5). A large cross-section of studies encompassing a range of econometric methods, sample periods and jurisdictions, reveals a strong easing impact on bank lending conditions. These studies cover the wide spectrum of the transmission channels mentioned above. A holistic approach combining all these studies is therefore likely to average out biases introduced by the absence of specific channels within the same study. The results of each paper are classified in terms of their period of reference and the corresponding TLTRO uptake, rescaling the impacts to account for differences in data, samples and methodologies.[18] This allows for a recasting of the respective elasticities in terms of the percentage increase of loan volumes per annum and basis points of impact on lending rates for each unit of TLTRO take-up. This results in an impact on loan volumes of above 2 percentage points each year, and on lending rates of over 60 basis points after the last operation in December 2021, against a counterfactual of nil participation. Importantly, this can be considered a conservative assessment of the actual impact of the operations, in particular with regard to their role as a backstop against a sharp deterioration in borrowing costs. This reflects that the sample period of the bulk of the studies does not feature episodes of financial and real economic stress of the magnitude experienced since the start of the COVID-19 crisis. Moreover, the absence of the TLTRO programme could have triggered a sharp deterioration in banks’ funding conditions, leading to a massive deleveraging episode. The effects of such a scenario are very difficult to quantify. Lastly, other pandemic response policies aimed at supporting bank lending, such as broadening collateral eligibility, capital relief measures and government guarantee schemes, are likely to have boosted the effectiveness of TLTROs even further.[19]

Chart 5

Meta-analysis of estimated impacts of TLTROs

a) Estimated impact of TLTRO take-up

(percentage points per annum)

b) Distribution of studies by approach and series

(percentages)

Sources: Afonso, A. and Sousa-Leite, J., “The transmission of unconventional monetary policy to bank credit supply: evidence from the TLTRO”, Working Papers, No 201901, Banco de Portugal, Lisbon, 2019; Altavilla, C., Barbiero, F., Boucinha, M. and Burlon, L., op. cit.; Altavilla, C., Canova, F. and Ciccarelli, M., “Mending the broken link: Heterogeneous bank lending rates and monetary policy pass-through”, Journal of Monetary Economics, Vol. 110, Issue C, Elsevier, 2020, pp. 81-98; Andreeva, D. C. and García-Posada, M., op. cit.; Arce, O., Gimeno, R. and Mayordomo, S., op. cit.; Balfoussia, H. and Gibson, H. D., “Financial conditions and economic activity: the potential impact of the targeted longer-term refinancing operations (TLTROs)”, Applied Economics Letters, Vol. 23, No 6, Taylor & Francis, London, 2016, pp. 449-456; Barbiero, F., Burlon, L., Dimou, M., Toczynski, J., “Targeted monetary policy during the pandemic: Evidence from TLTRO III”, forthcoming 2021; Bats, J. and Hudepohl, T., “Impact of targeted credit easing by the ECB: Bank-level evidence”, Working Papers, No 631, De Nederlandsche Bank, Amsterdam, 2019; Benetton, M. and Fantino, D., “Targeted Monetary Policy and Bank Lending Behavior”, Journal of Financial Economics, forthcoming 2021; Boeckx, J., de Sola Perea, M. and Peersman, G., “The transmission mechanism of credit support policies in the euro area” , European Economic Review, Vol. 124, Issue C, Elsevier, 2020; Cravo Ferreira, M., “What happens when the ECB opens the cash tap? An application to the Portuguese credit market”, dissertation, Universidade Católica Portuguesa, 2019; Esposito, L., Fantino, D. and Sung, Y., “The impact of TLTRO2 on the Italian credit market: some econometric evidence”, Working Papers, No 1264, Banca d’Italia, Rome, 2020; Flanagan, T., “Stealth Recapitalization and Bank Risk Taking: Evidence from TLTROs”, available at SSRN No 3442284; Gibson, H. D., Hall, S. G., Petroulas, P., and Tavlas, G. S., “On the effects of the ECB’s funding policies on bank lending”, Journal of International Money and Finance, Vol. 102, Issue C, Elsevier, 2020, pp. 1021-12; Laine, O., “The Effect of Targeted Monetary Policy on Bank Lending”, Journal of Banking and Financial Economics, forthcoming 2021; Offermans, C. J. and Blaes, B. A., “The Effects of Unconventional Monetary Policies on the Lending Activity of German Banks”, mimeo, 2021; Rostagno, M., Altavilla, C., Carboni, G., Lemke, W., Motto, R., Saint Guilhem, A., Yiangou, J., Monetary Policy in Times of Crisis: A Tale of Two Decades of the European Central Bank, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2021; van Dijk, M. and Dubovik, A., “Effects of Unconventional Monetary Policy on European Corporate Credit”, Discussion Papers, No 372, CPB Netherlands Bureau for Economic Policy Analysis, 2018.

Notes: Panel (a) shows average annual impact of TLTROs on loan growth to non-financial corporations for €2.2 trillion take-up. Estimates of each study are rescaled to take into account differences in data, samples and methodologies. Yellow bars report the median impact across studies. Dark blue areas correspond to the interquartile range, whiskers represent the range between 10th and 90th percentiles. Panel (b) shows percentages of studies on TLTROs covered in the meta-analysis by approach and programme of reference. Studies covering more approaches or programmes are counted multiple times when warranted, and the percentages are computed relative to the overall count.

TLTROs have staved off a sizeable part of the uncertainty about bank funding conditions and continue to provide a backstop function, conditional on the availability of spare borrowing allowances. The presence of TLTROs alone ensures that banks have access to ample funding at attractive conditions without stigma from participation into the programme, thereby increasing investor confidence and reducing the likelihood of adverse shocks in bank bond markets. Considering the outstanding amount of bank bonds by yield to maturity suggests that, if sizeable shocks to banks’ funding costs were nevertheless to materialise, this could prompt banks to replace a large fraction of their market funding with TLTROs. This highlights the importance of the TLTRO backstop function. Concretely, currently about 20% of banks’ outstanding bank bonds are priced below the deposit facility rate and more than half these bonds carry yields below the entry rate of TLTRO III. Some banks can thus still find it convenient to resort to market-based financing, if only to maintain their market access and for regulatory compliance purposes. However, a sudden shock to the cost of bond financing could make market-based financing considerably more expensive than central bank funding. At that point, banks could gradually replace the stock of their maturing debt with TLTRO III borrowing to the maximum possible extent given regulatory constraints and the residual spare capacity in terms of borrowing allowance. The current programme therefore serves as a backstop in case of the materialisation of severe distress in banks’ funding markets, but its effectiveness would in any case be constrained by the residual borrowing capacity of banks. Indeed, the availability of spare TLTRO borrowing capacity eases the decision for banks to venture into loan origination even in uncertain times by offering a comfortable level of liquidity and funding buffers to be accessed on demand. Simulations of a micro-structural model of the euro area banking system also show that the availability of attractive TLTROs helped to avoid adverse equilibria for banks’ riskiness, contributing to preserving accommodative funding conditions, above and beyond the actual reduction in the funding cost associated with TLTRO take-up.[20]

Moreover, the pass-through of TLTROs to lending conditions is complemented by other policy measures. The TLTRO incentive scheme motivates the channelling of borrowed funds to eligible lending. Yet, once the lending benchmarks are achieved, banks are likely to base their investment choices on the relative risk-adjusted return of alternative investment options. If this return is higher for lending to the private sector than for alternative uses of TLTRO funds, then banks have incentives to devote the necessary risk-bearing capacity to loan origination. Conversely, if the risk-adjusted return on loans falls below that of other assets, or if banks face de-facto quantitative capital constraints, they may find it more profitable to divert at least part of the funds into acquiring sovereign bonds or risk-free arbitrage with the ECB’s deposit facility. This has not been the case so far, partly because of complementary support from other policy areas. Asset purchase programmes have contained upward pressures on risk-free and sovereign yields, while microprudential and macroprudential actions have provided capital leeway for an expansion of credit to the private sector and government guarantees have substantially reduced banks’ exposure to the associated credit risk. From a longer-term perspective, the common fiscal instrument of the Next Generation EU programme has supported market expectations around a scenario of substantial fiscal support over the coming years. However, this balance could change for certain segments of the euro area banking system if faced with changes in the constellation of policies in place, such as a premature tightening of regulatory, supervisory or macroprudential policies, or delays in the deployment of the common fiscal instrument.

Soft information and econometric analysis of the impact of TLTROs on lending volumes and terms and conditions confirm that, alongside the stimulus to loan creation, there is no substantial increase in risk-taking by banks benefiting from the programme (Chart 6). While indicating a predominant profitability motive for participation and a recurring intended future use of TLTRO funds for granting loans to the private sector, euro area banks have consistently reported that TLTROs spur an increase in their lending volumes and a decrease in their lending rates, especially for loans to firms. Yet, the impact on credit standards, though it points towards an overall easing of criteria, has been moderating over time and especially relative to the early stages of the pandemic, when TLTRO incentives operated in strong interaction with government guarantee schemes and collateral and capital relief measures. The results of the euro area bank lending survey illustrated in Chart 6 show a negligible contribution to the easing of lending standards. This suggests relatively prudent lending behaviour on the part of participants. The results of this survey also point to a continued tightening of margins on riskier loans since the start of the pandemic, in contrast with broadly stable margins on average loans. Moreover, econometric evidence based on the euro area-wide credit register confirms that banks’ exposure to TLTROs was associated with an increase in lending concentrated towards ex ante safer borrowers, and that the registered increase was not associated with an increase in arrears ex post.[21]

Chart 6

Reported impact of TLTRO III on bank lending conditions

(net percentages of banks)

Source: Euro area bank lending survey.

Notes: Net percentages are defined as the difference between the sum of the percentages for “contributed considerably to a tightening or increase” and “contributed somewhat to a tightening or increase” and the sum of the percentages for “contributed somewhat to an easing or decrease” and “contributed considerably to an easing or decrease". The last period denotes expectations indicated by banks in the latest available round (April 2021) of the euro area bank lending survey.

Together with the stimulus to real economic activity provided by the easing of financing conditions, the impact of TLTROs on employment is likely to have been sizeable. It is generally challenging to analyse the effects of TLTRO III on the real economy, especially at such an early stage after the actual participation in TLTRO III operations. However, previous experience with TLTRO programmes, in situations characterised by a less pivotal role of the operations for bank lending conditions, shows the potential for significant real economic effects of TLTRO III, especially in conjunction with other policy areas activated during the pandemic, such as government guarantees and capital relief measures. A study finds that firms more exposed to TLTROs and capital relief measures tend to increase their employment levels significantly. The impacts predicted for the current juncture based on historical regularities are economically meaningful. Considering the reduction in bank funding cost brought forth by the TLTROs and the capital relief observed over the period between March and April 2020, the overall impact of the policy measures implemented in response to the pandemic has the potential to forestall an employment decline in the corporate sector of more than one million workers over the period 2020-2022.[22]

Box 3

The redistribution of central bank reserves borrowed under TLTRO III

Banks receive central bank reserves when they borrow from the Eurosystem through its refinancing operations, such as TLTRO III, or when they sell or intermediate the sale of securities to the Eurosystem in the context of asset purchase programmes (see Table A). Those central bank reserves can only be stored on banks’ accounts with the Eurosystem. Accordingly, the aggregate volume of banks’ central bank reserve holdings with the Eurosystem mechanically reflects the liquidity injected by refinancing operations and asset purchases.

Table A

Creation of central bank reserves

(EUR)

Source: ECB.

Note: The table shows the change in balance sheet items following a €10 refinancing operation from Bank A and a €5 outright asset purchase from Bank B.

Notwithstanding these aggregate dynamics, central bank reserve holdings can circulate between banks when these holdings are used to settle interbank transactions. For instance, when a bank buys a security, e.g. a sovereign bond from another bank, it could pay the other bank by transferring some of its central bank reserves. Moreover, when households and firms make regular payment transactions, central bank reserves are transferred across banks. A bank that experiences an outflow of deposits could settle the transaction by transferring some of its central bank reserves to the bank that experiences an inflow. Finally, banks could issue or repay interbank loans and thereby redistribute central bank reserves.[23]

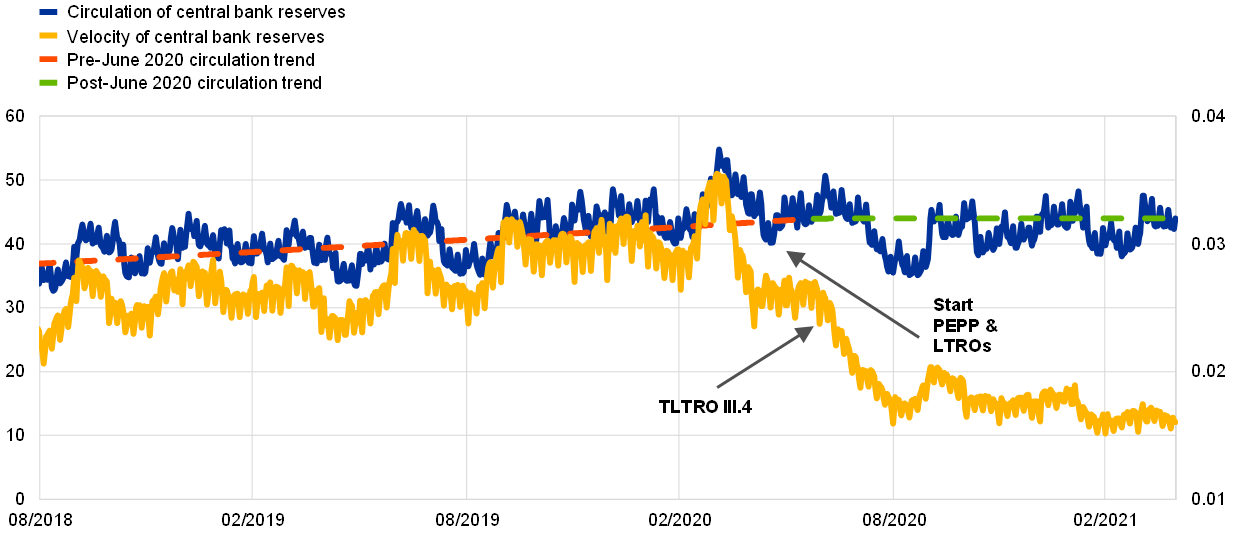

Chart A

The circulation and velocity of central bank reserves

(left-hand scale: EUR billions; right-hand scale: ratio)

Source: ECB.

Notes: The chart shows the circulation of central bank reserves which is computed as the 30-day moving average of the sum of all absolute daily changes in banks’ excess liquidity holdings, corrected for changes that are caused by the settlement of refinancing operations and asset sales to the Eurosystem, divided by two. The velocity of central bank reserves is obtained by dividing the latter metric by banks’ total holdings of excess liquidity (central bank reserves in excess of their minimum reserve requirements) to obtain the percentage of aggregate excess liquidity holdings used for daily interbank transactions. The latest observation is for 1 May 2021.

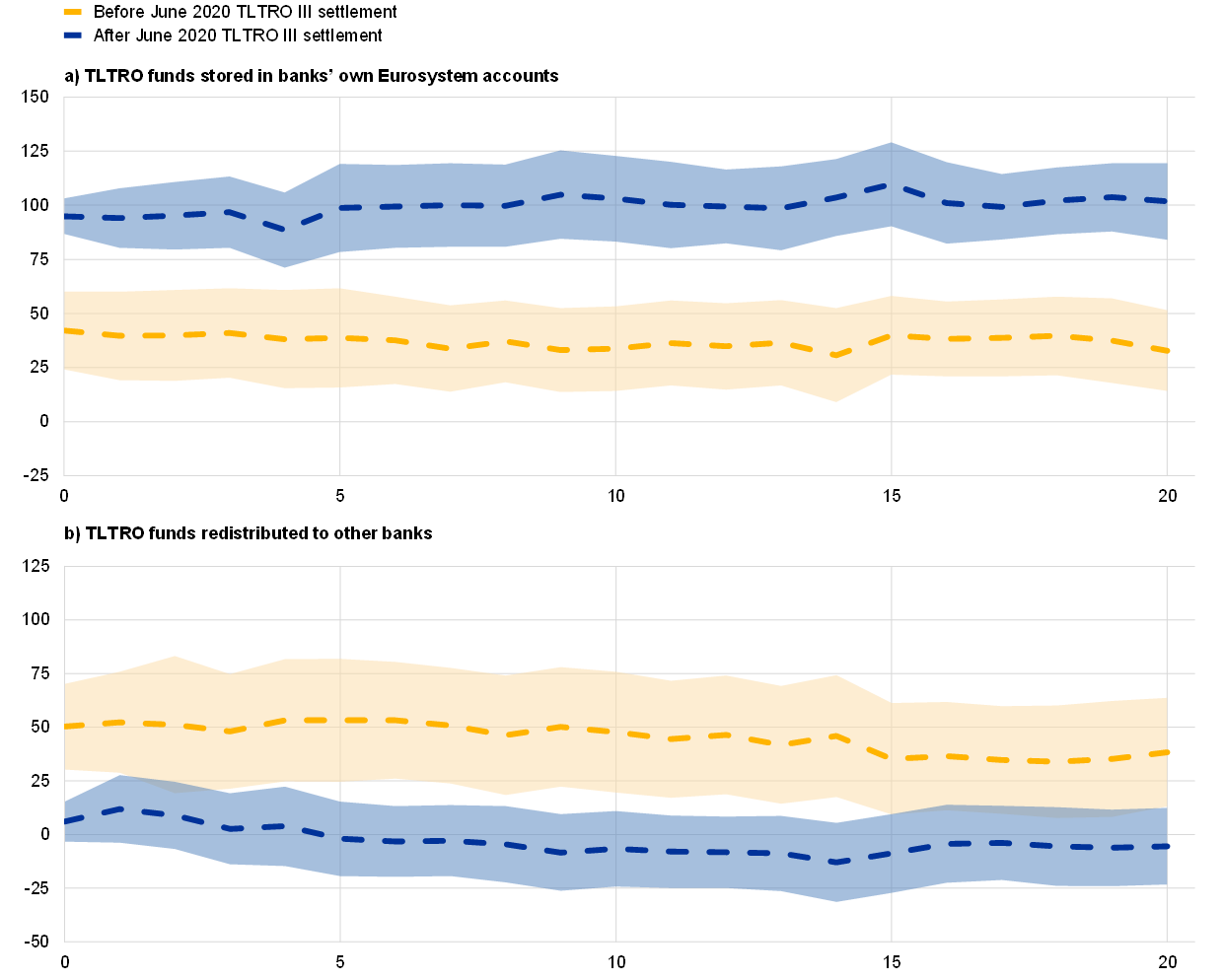

The redistribution of central bank reserves has declined substantially since the announcement of the additional longer-term refinancing operations (LTROs) and the pandemic emergency programme (PEPP) in March 2020. It decreased further after the settlement of the June 2020 TLTRO III. Before the pandemic, the total circulation of central bank reserves – measured by summing over all flows of central bank reserves between banks – increased steadily over time (blue line in Chart A). The circulation of central bank reserves was closely mirrored by the velocity of central bank reserves: the percentage of aggregate central bank reserve holdings in excess of banks’ minimum reserve requirements used for daily interbank transactions (yellow line in Chart A). Following the start of the additional LTROs and the PEPP in March 2020 and more pronouncedly after the settlement of the June 2020 TLTRO III (the first operation after the April TLTRO III recalibration introduced more favourable terms), the circulation of central bank reserves stabilised, while the velocity of central bank reserves declined sharply.[24] A more formal statistical approach confirms that the redistribution of central bank reserves has declined. While historically only about half of the borrowed reserves were stored on banks’ own accounts with the Eurosystem in the weeks following TLTRO settlement (yellow lines in Chart B), since the June 2020 TLTRO III banks appear to store close to all the borrowed reserves in their accounts with the Eurosystem (blue lines Chart B).

Chart B

Estimated percentage of TLTRO funds that banks stored and redistributed

(y-axis: percentages; x-axis: days after TLTRO settlement)

Source: ECB calculations.

Notes: The estimated coefficients in the chart are based on a panel data local projections model which relates daily changes in a bank’s excess liquidity holdings to: its own TLTRO borrowing, panel (a); TLTRO borrowing by other banks in the Eurosystem, panel (b), controlling for other refinancing operations; the bank’s own asset sales and asset sales by other banks to the Eurosystem; redemptions of assets bought by the Eurosystem; and autonomous factors at the euro area level. The first estimation period is August 2014 to 31 May 2020 for settlement before the June 2020 TLTRO, and 1 June 2020 to 1 May 2021 for settlement after the June 2020 TLTRO III. As the results are model-based and due to noise in the data and the inability to fully control for autonomous factors at the bank level (as such data are not available), the sum of funds stored in banks’ own Eurosystem accounts and TLTRO funds redistributed to others do not exactly add up to 100% and are subject to uncertainty as reflected by the shaded areas denoting 90% confidence intervals.

Several factors could explain the decline in the redistribution of central bank reserves. First, the decline in economic activity and the increase in households’ and firms’ savings reduced payment flows and thereby reduced the need for banks to use central bank reserves to settle payment transactions. Second, the more favourable pricing of TLTRO III and the alleviation of regulatory rules over the pandemic emergency period allowed banks to build a precautionary liquidity buffer at little to no costs. This has likely increased TLTRO III participation while it has decreased the pecuniary incentive to redistribute the obtained central bank reserves. Finally, the increase in the number of banks participating in TLTRO III has potentially reduced the scope for redistributing central bank reserves to non-participating banks

4 Conclusions

TLTRO III has been effective in protecting bank-based transmission during the pandemic. Previous TLTROs already supported borrowing conditions for households and firms long before the COVID-19 pandemic hit the euro area. The recalibrations of TLTRO III in the first half of 2020 propelled the programme into a much wider role, as a central bulwark against the impairment of the bank-based transmission mechanism of monetary policy in a context of unprecedented financial stress for the euro area banking system. The largest liquidity injection in the history of the ECB, in June 2020, followed by robust participation in the subsequent operations, has provided central bank liquidity at attractive rates under the condition of complying with demanding and yet achievable lending targets for euro area banks. The stimulus coming from the enhanced operations was transmitted in various ways to lending conditions above and beyond the explicit lending criteria ingrained in the programme. This has helped to secure favourable financing conditions to households and firms throughout the pandemic. Since the stimulus to lending conditions via banks is generally transmitted with a lag, the overall impact of TLTROs has not yet fully materialised.

There is no evidence of substantial side effects or dilution of the stimulus coming from TLTROs so far, with the programme interacting positively with the broader policy package. By supporting lending margins, the programme granted banks enough leeway to extend credit to the private sector without necessarily scaling up the risk spectrum, especially against the background of the unprecedented demand for emergency liquidity needs expressed by corporates in the early stages of the pandemic. There is also evidence that the design of TLTROs ensured that the stimulus reached households and firms as intended, without being excessively diluted by unwarranted uses of funds such as lending to governments. The effectiveness of TLTROs in transmitting the accommodative conditions to the targeted sector was substantially supported by the contribution of other monetary policy instruments such as asset purchases, forward guidance and negative interest rate policy as well as collateral easing measures, which worked in unison with TLTROs, as well as contributions from other policy domains like microprudential and macroprudential policies or fiscal policy via, for example, the provision of government guarantees.

TLTROs offering conditional funding at rates below the deposit facility rate are an effective and flexible tool of monetary policy accommodation in the vicinity of the effective lower bound, especially in an environment characterised by a high level of uncertainty. The targeting element is a key feature of the operations, increasing banks’ incentives for lending. The conditional pricing of TLTROs below the deposit facility rate has created additional room for easing funding conditions for banks in a negative interest rate environment and offers an effective backstop against strains in banks’ access to market-based funding. Moreover, the close link with the deposit facility rate has allowed the negative interest rate policy to continue spurring loan origination, even as deposit rates fell further.

- See Rostagno, M., Altavilla, C., Carboni, G., Lemke, W., Motto, R., Saint Guilhem, A., Yiangou, J., Monetary Policy in Times of Crisis: A Tale of Two Decades of the European Central Bank, Oxford University Press, 2021 and the article entitled “The transmission of the ECB’s recent non-standard monetary policy measures”, Economic Bulletin, Issue 7, ECB, 2015.

- The recalibration of TLTRO III was critically supported by temporary adjustments to the ECB collateral framework. Moreover, it was complemented by the introduction of pandemic emergency long-term refinancing operations (PELTROs), the temporary availability of longer-term refinancing operations with maturity coincident with the earliest available TLTRO III operation after the recalibrations of March and April 2020 (referred to as bridge LTROs), and central bank swap and repo lines across the globe that provided euro and foreign currencies.

- For more details, see ECB press release of 12 March 2020.

- For more details, see ECB press release of 30 April 2020.

- For more details, see ECB press release of 10 December 2020.

- See ECB press release of 7 April 2020 and ECB press release of 22 April 2020.

- Collateral easing is measured as the difference between the actual value of collateral mobilised and the estimated amount of collateral mobilised, valued at non-pandemic (regular) conditions. Collateral easing measures comprise only the temporary measures taken in response to the coronavirus pandemic, valid until June 2022. The estimates exclude the impact of the softening of certain operational requirements such as the reporting frequency of pools of ACCs.

- For more details on the scope, eligibility criteria and pandemic-related expansions of additional credit claims see the ECB explainer “What are additional credit claim (ACC) frameworks?”

- See Andreeva, D.C. and García-Posada, M., “The impact of the ECB's targeted long-term refinancing operations on banks’ lending policies: The role of competition”, Journal of Banking & Finance, Vol. 122, No 105992, Elsevier, January 2021, and Benetton, M. and Fantino D., “Targeted monetary policy and bank lending behavior”, Journal of Financial Economics, forthcoming.

- The indirect reduction in bank funding cost therefore also supports lending for banks not directly participating in the programme. Moreover, while the targeting feature stimulates lending to the eligible sector, these more favourable funding costs can stimulate lending more broadly, also to the non-eligible sector.

- See Arce, O., Gimeno, R. and Mayordomo, S., “Making Room for the Needy: The Credit-Reallocation Effects of the ECB’s Corporate QE”, Review of Finance, Vol. 25, Issue 1, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2020, pp. 43–84.

- In order to attain the minimum interest rate on TLTRO III operations, participating banks need to meet a threshold above their lending benchmark over a certain evaluation period. In March 2020 a new evaluation period for banks’ lending performance was introduced, which was modified in April 2020 to include the 13-month period from March 2020, in order to provide further incentives for banks to maintain the level of credit support that they have provided since the start of the pandemic.

- The recalibration of 10 December 2020 prolonged the -1% interest rate to June 2022, subject to an additional lending requirement based on the lending performance measured between October 2020 and December 2021.

- See the box entitled “Public loan guarantees and bank lending in the COVID-19 period”, Economic Bulletin, Issue 6, ECB, 2020 and M. Falagiarda and P. Köhler-Ulbrich “Bank Lending to Euro Area Firms – What Have Been the Main Drivers During the COVID-19 Pandemic?”, European Economy, Issue 1, April 2021.

- The accumulation of deposits with the Eurosystem is also visible among banks that did not participate in TLTRO III (see panel (a), Chart 3).

- Individual banks can engineer a reduction in their own excess liquidity position by, for instance, employing it to grant a new loan. However, unless the borrower withdraws the full amount of the loan and keeps it in banknotes, the funds will find their way back to a deposit at the same or another bank, offsetting the initial decrease in excess liquidity. For more details see the ECB explainer “What is excess liquidity and why does it matter?”

- This is in line with the individual responses of participants in the October 2020 euro area bank lending survey to questions related to the motivation to participate in future TLTROs.

- Moreover, the survey evidence discussed above suggests that the sheer magnitude of TLTRO III borrowing in the wake of the pandemic could lead to a more diversified use of funds. In a conservative approach, the exercise uses this information to rescale the estimates of studies conducted on pre-pandemic data. The estimates based on post-pandemic data are not affected.

- See, for example, Altavilla, C., Barbiero, F., Boucinha, M. and Burlon, L., “The great lockdown: pandemic response policies and bank lending conditions”, Working Paper Series, No 2465, ECB, Frankfurt am Main, September 2020.

- In particular, it is estimated that a 1 percentage point reduction in TLTRO rate reduces the median bank’s default risk by around 50%, with increasing effectiveness for banks more exposed to fundamental risk. See Albertazzi, U., Burlon, L., Jankauskas, T, Pavanini, N., “The (unobservable) value of central bank’s refinancing operations”, Working Paper Series, No 2480, ECB, Frankfurt am Main, October 2020.

- See Barbiero, F., Burlon, L., Dimou, M., Toczynski, J. “Targeted monetary policy during the pandemic: Evidence from TLTRO III”, forthcoming 2021.

- See, for example, Altavilla, C., Barbiero, F., Boucinha, M. and Burlon, L., “The great lockdown: pandemic response policies and bank lending conditions”, Working Paper Series, No 2465, ECB, Frankfurt am Main, September 2020.

- Notably, banks cannot use central bank reserves directly for lending to households and firms because the latter do not have an account with the Eurosystem.

- The velocity of reserves observed depends on banks’ holdings of central bank reserves at the end of the day. Therefore, it is possible to have a high intra-day and/or intra-bank velocity while the amount of reserves held by each bank at the end of the day remains relatively stable.