Implications for macroprudential policy as the financial cycle turns

This article discusses the role of macroprudential policy in the current environment. Although the euro area financial cycle is turning, banks remain profitable, vulnerabilities are still elevated, and financial stability risks have not yet materialised. Against this backdrop, macroprudential policy should not be loosened but should instead focus on preserving the resilience of banks and borrowers.

1 Where do we stand in the financial cycle?

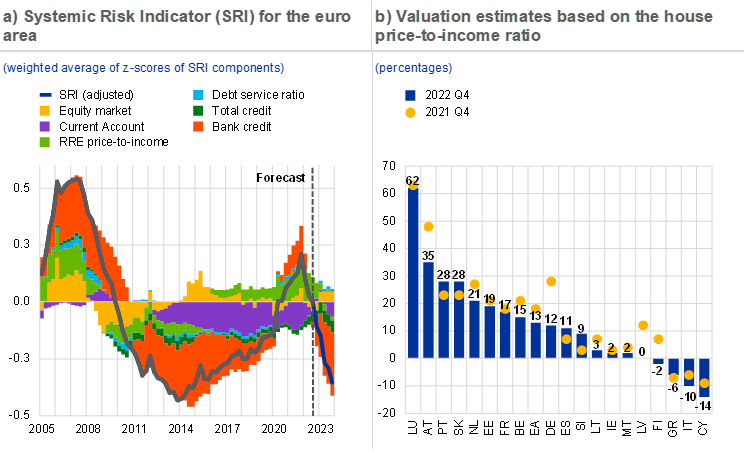

The financial cycle in the euro area has turned and is expected to fall further amid rising interest rates and challenging macro-financial conditions. The euro area systemic risk indicator (SRI)[1], which captures credit and asset price dynamics, peaked at the end of 2021 and has since declined. The fall in the indicator is due to (i) the dropping out of base effects related to the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic and (ii) the recent deceleration in bank credit and real estate price growth amid rising interest rates (Chart 1, panel a). Given the challenging macro-financial environment of moderate growth, elevated inflation and tightening financial conditions (see the overview in ECB, 2023b), the financial cycle is expected to maintain its downward trend in the coming quarters. Although house prices started to fall in some Single Supervisory Mechanism (SSM) countries in the second half of 2022, price adjustments have been small so far, and price valuation estimates, such as house-price-to-income ratios, remain elevated in many countries (Chart 1, panel b). Further downward pressure on house prices can therefore be expected, as elevated prices and higher interest rates have lowered housing affordability considerably. This is showing up in significantly lower mortgage loan demand from households due to the weaker housing market outlook.[2]

Credit growth has decelerated markedly in recent months, but this is primarily driven by lower loan demand and not by bank capital constraints. While bank loan growth was still strong in the first half of 2022, bank loan dynamics have slowed considerably across countries since autumn 2022.[3] Lower bank loan growth mainly reflects weaker loan demand due to higher interest rates, lower fixed investment needs, weaker housing market prospects and subdued economic sentiment. While bank credit standards are also tightening, this is less pronounced than the fall in loan demand. Most importantly from a macroprudential policy perspective, the tightening in bank credit standards is so far not driven by bank capital constraints according to results from the ECB’s bank lending survey[4] and a survey conducted among national authorities of SSM countries. Instead, the main drivers of tightening credit standards are increased risk perceptions, lower risk tolerance and rising financing costs, as would be expected in an environment with moderate growth, elevated inflation and tightening monetary policy.

Chart 1

The financial cycle has peaked, but vulnerabilities remain elevated

Source: ECB calculations.

Notes: Panel a): The SRI is based on Lang et al (2019). The SRI is a broad-based cyclical systemic risk measure that captures risks stemming from domestic credit, real estate markets, asset prices and external imbalances. It is constructed as the optimal weighted average of six sub-indicators with weights chosen to maximise the early warning properties of the composite SRI for systemic financial crises. The six sub-indicators that make up the SRI are (i) the two-year change in the bank credit-to-GDP ratio (36% weight), (ii) the two-year growth rate of real total credit (5% weight), (iii) the two-year change in the debt service-to-income ratio (5% weight), (iv) the three-year change in the residential real estate (RRE) price-to-income ratio (17% weight), (v) the three-year growth rate of real equity prices (17% weight), and (vi) the current account-to-GDP ratio (20% weight). Indicators underlying the SRI are normalised to the same scale by subtracting the median and dividing by the standard deviation of the pooled indicator distribution across euro area countries. An SRI value of +1 can be interpreted as all sub-indicators being one standard deviation above their median value from the pooled historical indicator distribution across euro area countries. The SRI is adjusted for the GDP drop during the COVID-19 pandemic by assuming the 2019 GDP level if current GDP is still below it. SRI nowcasts and forecasts are based on March 2023 MPE data. Panel b): Estimates of the valuation of residential property prices are based on the price-to-income ratio (for details, see Box 3 in Financial Stability Review, ECB, June 2011 and Box 3 in Financial Stability Review, ECB, November 2015).

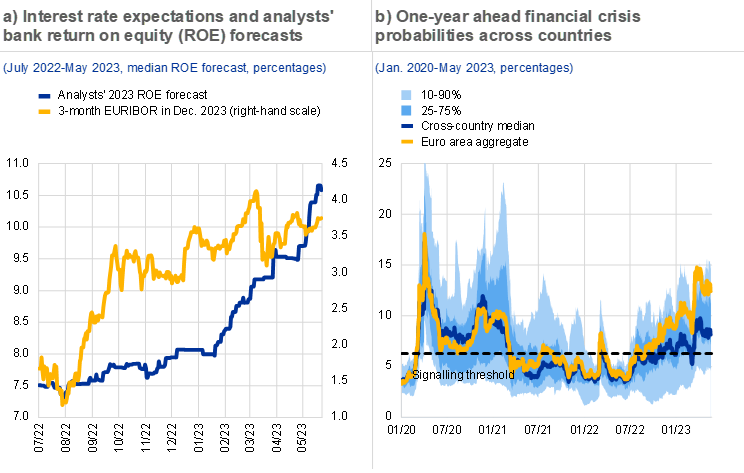

So far, the turn in the financial cycle has been orderly, but vulnerabilities are still present and financial stability risks could materialise in the future. A slowdown in credit growth and fall in real estate prices are in line with expectations after years of robust growth rates and the current rise in interest rates. As long as further adjustments remain orderly, they will help to reduce existing vulnerabilities and imbalances over the medium term. Currently, bank asset quality is still good, bank profitability levels are at multi-year highs, and markets expect bank profitability to increase further in 2023 (Chart 2, panel a). However, banks face headwinds (see ECB, 2023b), and past regularities show that financial stability risks often materialise when the financial cycle turns abruptly. In line with this historical pattern, early warning models show an increase in the near-term financial crisis probability over recent months, also after the March bank stress episodes in the United States and Switzerland, but remain below the pandemic levels (Chart 2, panel b). The most significant vulnerabilities in the euro area that could play a role in a disorderly adjustment in adverse scenarios relate to (i) high indebtedness and weakening debt servicing ability of non-financial sectors in some countries, (ii) funding and asset quality headwinds for banks, (iii) vulnerability to further repricing in financial markets, (iv) overvaluation in real estate markets, and (v) liquidity and credit risk in non-banks (see ECB, 2023b).

Chart 2

Banks remain profitable, but the likelihood that risks could materialise has increased

ources: Bloomberg and ECB calculations.

Notes: Panel a): Median of analyst ROE forecasts across banks. Panel b): The model predicts the country-level probability of a systemic financial crisis within the next year. Explanatory variables: equity price volatility and growth, yield curve slope, consumer confidence indicator, change in the non-financial private sector debt service-to-income ratio. Blue shaded areas indicate percentile ranges across euro area countries.

2 Implications for capital-based measures

In the current environment, capital-based macroprudential policy should focus on preserving the resilience of the banking system. As discussed in Section 1, although the financial cycle has turned, accumulated vulnerabilities remain elevated in several SSM countries. At the same time, the likelihood that financial stability risks could materialise has increased, and the March 2023 banking sector turmoil in the United States has highlighted potential vulnerabilities in relation to liquidity and interest rate risk. While euro area banks have proven to be resilient and profitable in the face of recent stress events, the possibility of further adverse macro-financial or geopolitical shocks means that macroprudential authorities need to closely monitor developments and flexibly adjust the course of action when required. For now, as financial stability risks have not materialised, the focus should be on preserving banking sector resilience.

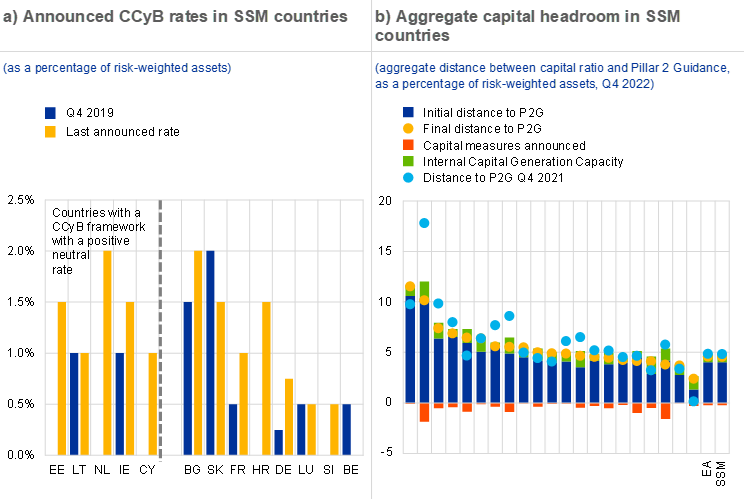

Capital measures implemented since the pandemic have an important role to play in preserving banking sector resilience, and buffers should not be released at this stage. Many national authorities in the euro area have increased macroprudential capital buffers since the COVID-19 pandemic, especially via the countercyclical capital buffer (CCyB), despite facing the challenges brought about by a highly uncertain geopolitical and economic environment (see Chart 3, panel a). These buffer increases have further enhanced the resilience of the euro area banking system. The main factors that should guide decisions on whether to release these capital buffers relate to (i) a potential tightening of bank credit supply due to capital constraints and (ii) an increased likelihood of widespread materialisation of bank losses (see Box 1). Neither of these conditions is currently observed. While there are some indications of credit supply tightening driven by higher risk perceptions, lower risk tolerance, and – to a limited extent – banks’ liquidity positions (Section 1), capital requirements are not seen as a constraining factor for loan supply, as banks still have ample capital headroom at an aggregate level and remain profitable (Chart 3, panel b). On the contrary, maintaining sufficiently strong capital buffers may help to reduce the likelihood of financial stability risks materialising on the liquidity side (for example by enhancing creditor confidence), which appears to be among the main drivers of concerns about a future potential credit crunch. In addition, maintaining these buffers preserves authorities’ ability to release capital in response to potential future shocks. Such shocks could cause more widespread losses, in turn making capital requirements more binding and then exerting a negative impact on credit supply that could be mitigated via a buffer release.

Chart 3

Authorities have actively increased CCyB rates in recent quarters while banks in the SSM area still have ample capital headroom

Sources: ECB and ECB calculations.

Notes: Panel a): CCyB rates announced before the pandemic and latest announced CCyB rates. For the sake of simplicity, countries on the left are referred to as having “a CCyB framework with a positive neutral rate”, although some of them prefer to use the expression of a “positive rate in a standard [or low] risk environment”. Panel b): The sample of banks covers 2,416 significant and less significant institutions, consolidated at country level. Bars refer to individual countries, where aggregation at country level is done with averages weighted by risk-weighted assets. Capital headroom is defined as the part of the CET1 ratio in excess of the sum of the Pillar 1 and Pillar 2 requirements, the combined buffer requirement, any applicable AT1/T2 shortfall, and Pillar 2 Guidance. The impact of capital measures that have already been announced but not yet implemented is shown in red (this captures forthcoming foreign and domestic macroprudential measures). Internal capital generation capacity (green bars) is defined as the bank’s annual profits (Q1 2022-Q4 2022) after dividends and share buybacks (assumed equal to 40% of profits if positive, 0% if the profits are negative), which are assumed to be stable in 2023. The final “free” capital headroom (yellow dots) in 2023-Q4 is calculated as the sum of the currently observed (initial) capital headroom in 2022-Q4 (blue bars), capital generation capacity, and the impact of already announced measures. This capital headroom estimate does not consider the impact of parallel requirements, such as the leverage ratio or minimum requirement for own funds and eligible liabilities (MREL), that may reduce effective headroom in some cases.

While the bulk of the policy action has been taken, targeted increases in buffer rates could still be considered in selected countries with vulnerabilities, as long as the risk of procyclicality remains low. In line with their substantial capital headroom, most banks in the SSM area continue to operate above their publicly announced capital ratio targets, which alleviates pressure to make adjustments in response to potentially higher buffer requirements. In addition, bank profitability should remain solid in a baseline scenario. At the same time, downside risks are elevated because of expected increases in provisioning, increased interest rate risk and the possibility of further macro-financial or geopolitical shocks mentioned above (see ECB, 2023b), which justifies the macroprudential objective of preserving banking sector resilience. In such an environment, it is a robust policy strategy to “buy insurance when costs are low”, as most banks should be able to cope with moderate buffer increases without needing to cut lending.[5] Macroprudential capital buffers also provide banks with the right incentives to focus on preserving or further increasing their resilience and limit potentially less conservative payouts that could occur in an environment where banks may feel compelled to signal their strength.[6] Nevertheless, any policy action needs to be carefully tailored to country-specific conditions and avoid triggering procyclical adjustments, given that capital headroom varies across countries and banks and may also be constrained by other requirements such as the leverage ratio and the minimum requirement for own funds and eligible liabilities (MREL).

For countries with a positive neutral CCyB framework, the build-up of the buffer is a welcome development. An increasing number of euro area countries have established a framework that envisages a positive rate for the CCyB even before cyclical systemic risks become elevated (Chart 3, panel a).[7] The adoption of a framework with a positive neutral rate has several advantages and is consistent with a broader international move, observed since the COVID-19 pandemic, towards the more active use of the CCyB.[8] While the buffer should ideally be built up at an early stage of the cycle, the current late stage should not prevent countries from action if the economic costs of doing so remain low[9] and benefits are expected to arise from a further build-up. Over the medium term, more widespread adoption of frameworks with a positive neutral rate remains desirable as a way of enhancing consistency and ensuring effective policymaking while providing for sufficient national flexibility.[10]

3 Implications for borrower-based measures

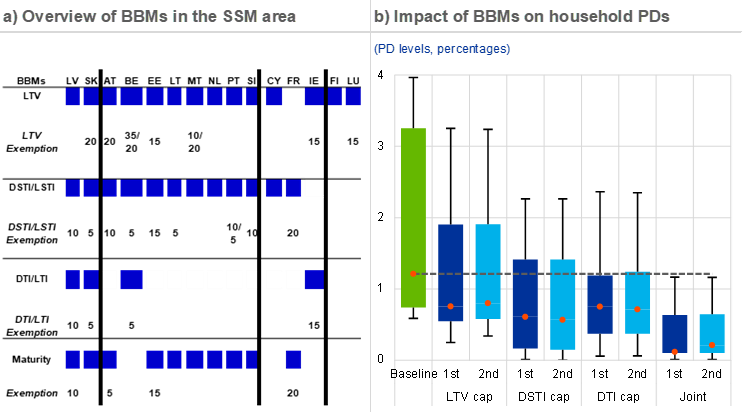

Borrower-based measures (BBMs) in the SSM area are under the remit of national authorities and, in the current environment, have an important role to play in containing risky lending flows. Income-based BBMs, such as loan-to-income (LTI) and loan service-to-income (LSTI) limits, aim to keep household indebtedness in check and ensure that debt servicing ability can be sustained, thereby supporting borrower and bank resilience. Collateral-based BBMs, such as loan-to-value (LTV) limits, protect against the impact of residential real estate (RRE) price corrections.[11] Both income-based and collateral-based BBMs have been widely implemented by national authorities in the SSM area and are largely designed as structural backstop measures, curtailing excessively risky lending flows at the right tails of lending standard distributions throughout the cycle and often including targeted exemptions that provide banks with flexibility (Chart 4, panel a). These exemptions can also address unintended consequences related to certain borrower groups’ access to credit, while keeping the measures focused overall on financial stability objectives. The effectiveness of existing BBMs is illustrated by model-based simulations that show a gradual but notable increase in the resilience of borrowers and therefore banks over the medium term (Chart 4, panel b).

Chart 4

BBMs have been implemented across a broad set of SSM countries and help to gradually increase borrower and bank resilience

Sources: ECB and ECB calculations, Giannoulakis et al. (2023), Household Finance and Consumption Survey.

Notes: Panel a): Countries are grouped according to the number of borrowed-based measures in place. LTV, DSTI/LSTI, DTI/LTI and Maturity limit exemptions are expressed as percentages. Belgium (BE): LTV exemption rates refer to first time buyers and to second and subsequent buyers. Malta (MT): LTV exemption: Malta distinguishes between category I and category II borrowers. For category I borrowers an exemption rate of 10% applies, while for category II borrowers an exemption rate of 20% applies. Portugal (PT): debt service-to-income (DSTI) exemption: 10% of loans can be granted to borrowers with a DSTI of up to 60%, while 5% of total loans can be granted to borrowers with a DSTI above 60%. Slovakia (SK): LTV exemption: for up to 20% of new loans, the LTV ratio may be up to 90%. The abbreviation “DTI” stands for “debt-to-income”. Panel b): Boxes and whiskers are, respectively, interquartile ranges and minima/maxima of probabilities of default (PDs) across countries; red dots are medians. The green box and the dotted median line refer to the PDs without BBMs in place (no policies), while the dark blue boxes refer to the first-round impact of the policies. The light blue boxes reflect the effects after taking into account second-round macroeconomic effects from the policy-induced negative credit demand shock. Details of the country-specific calibration of BBMs are available in Giannoulakis et al. (2023).

Higher interest rates and elevated inflation pose challenges for existing BBMs, as they put upward pressure on LSTI ratios and increase the riskiness of a given lending standard at origination. In an environment where house price growth is stalling or even negative (Section 1), loan amounts needed to buy a house are no longer increasing, and therefore LTV and LTI ratios for new loans seem to be stable or declining on average in most countries (Box 2). By contrast, the rapid rise in interest rates has put upward pressure on the LSTI ratios of new loans in several countries. At the same time, the riskiness implied by a given LTV ratio at origination appears to be higher than in previous years, since valuation estimates remain elevated and RRE prices are expected to fall further in many countries. The implied riskiness of a given LTI or LSTI ratio at origination also appears to be higher at the moment, as elevated expenditure inflation reduces net disposable income for many borrowers and therefore implies higher net LTI and net LSTI ratios. Given the increased riskiness of a given ratio, preserving sound and sustainable lending standards through BBMs appears particularly important in the current environment.

In the light of the above and considering the structural nature of these measures, national authorities should maintain existing BBMs to support household and bank resilience. BBMs, once implemented, are mostly intended to remain stable over the financial cycle and are aimed at curbing excessively risky lending during all cycle phases. This resonates with the conceptual arguments outlined above: as pressure on LTI and LTV ratios is currently receding, while riskiness implied by given LTI and LTV ratios has increased, there is little reason to loosen existing BBMs for these lending standards. By contrast, for LSTI limits there is a potential trade-off between ensuring continued safe lending flows on the one hand and avoiding a potential amplification of the RRE cycle downturn due to overly binding limits on the other hand. However, existing design elements such as exemptions or looser limits for specific types of borrowers already provide flexibility and mitigate the risk of procyclicality (see Box 2 on remaining flexibility to lend above DSTI limits). In addition, other factors (higher borrowing costs, reduced credit demand and tighter lending standards irrespective of policy measures) appear to be more relevant than BBMs in constraining mortgage lending at the current stage. Thus, on balance it appears advisable for national authorities to keep existing LSTI limits in place to prevent excessively risky mortgage lending, which also remains relevant from a financial stability perspective in a more challenging macro-financial environment. Of course, should conditions deteriorate further and make existing LSTI limits more binding, targeted adjustments (such as temporary relaxations of exemptions) could be considered in some countries in the future.

4 Conclusion

Overall, in the current environment macroprudential policy should focus on preserving the resilience of banks and borrowers to potential future adverse shocks. As this article has shown, there are clear signs that the financial cycle in the euro area is turning. Should macroprudential policy therefore be loosened? This article has argued that the answer is no, as banks remain profitable, vulnerabilities are still present, financial stability risks have not yet materialised, and preventing excessively risky mortgage lending also remains relevant from a financial stability perspective given the more challenging macro-financial conditions. Instead, in the current environment macroprudential policy should focus on preserving the resilience of banks and borrowers so that the financial system can safely weather potential future adverse developments while continuing to provide key services to the real sector. Macroprudential authorities are closely monitoring current developments and can flexibly adjust the course of action if necessary. In particular, buffers could be released if financial stability risks were to materialise, or targeted adjustments could be made to existing BBMs (such as temporarily higher exemptions) if these measures became more binding in the future.

References

Acharya, V., Gujral, I., Kulkarni, N. and Shin, H. (2022), “Dividends and Bank Capital in the Global Financial Crisis of 2007–2009”, Journal of Financial Crises, Vol. 4, No 2, pp. 1-39.

Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (2022), “Newsletter on positive cycle-neutral countercyclical capital buffer rates”, Bank for International Settlements, October.

Behn, M., Pereira, A., Pirovano, M. and Testa, A. (2023), “A positive neutral rate for the countercyclical capital buffer – state of play in the banking union”, Macroprudential Bulletin, No 21, ECB, Frankfurt am Main, April.

European Central Bank (2021), “Financial Stability Review”, Frankfurt am Main, November.

European Central Bank (2023a), “Economic Bulletin”, Issue 2, Frankfurt am Main.

European Central Bank (2023b), “Financial Stability Review”, Frankfurt am Main, May.

Giannoulakis, S., Forletta, M., Gross, M. and Tereanu, E. (2023), “The effectiveness of borrower-based macroprudential policies: a cross-country perspective”, Working Paper Series, No 2795, ECB, Frankfurt am Main, March.

Lang, J.H., Izzo, C., Fahr, S. and Ruzicka, J. (2019), “Anticipating the bust: a new cyclical systemic risk indicator to assess the likelihood and severity of financial crises”, Occasional Paper Series, No 219, ECB, Frankfurt am Main, February.

Lang, J.H, Pirovano, M., Rusnák, M. and Schwarz, C. (2020), “Trends in residential real estate lending standards and implications for financial stability”, Financial Stability Review, ECB, Frankfurt am Main, May.

Lang, J.H. and Menno, D. (2023), “The state-dependent impact of changes in bank capital requirements”, Working Paper Series, ECB, forthcoming.

Lo Duca, M., Bartal, M., Giedraitė, E., Granlund, P., Hallissey, N., Jurča, P., Kouratzoglou, C., Lennartsdotter, P., Lima, D., Pirovano, M., Prapiestis, A., Saldias, M., Sangaré, I., Serra, D., Silva, F., Tereanu, E., Tuomikoski, K. and Vauhkonen, J. (2023), “The more the merrier? Macroprudential instrument interactions and effective policy implementation”, Occasional Paper Series, No 310, ECB, Frankfurt am Main, March.

Tereanu, E., Behn, M. and Lang, J.H. (2022), “The transmission and effectiveness of macroprudential policies for residential real estate”, Macroprudential Bulletin, No 19, ECB, Frankfurt am Main, October.

The SRI is a broad-based measure of the financial cycle that captures risks stemming from domestic credit, real estate markets, asset prices and external imbalances. Further details can be found in the notes to Chart 1 and in Lang et al (2019).

See, for example, the results of the ECB’s bank lending survey for the first quarter of 2023.

See, for example, the March 2023 ECB BSI data or Section 5 of ECB (2023a).

See the results of the ECB’s bank lending survey for the first quarter of 2023.

As long as there is enough capital headroom and profitability to allow banks to meet gradual increases in capital buffer requirements, the impact on bank loan supply should be very low. See, for example, Lang and Menno (2023).

During the global financial crisis of 2007-09, many banks continued with large-scale payments of dividends despite widely expected credit losses (see, for example, Acharya et al., 2022). Higher capital buffers give banks the incentive to retain capital and thus help to address this potential pitfall.

Specifically, frameworks including a positive neutral rate for the CCyB are currently in place in five euro area countries, namely Lithuania since the end of 2017, Estonia since the end of 2021, and Ireland, Cyprus and the Netherlands since 2022. Outside the euro area, Australia, Canada, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Norway, Sweden and the United Kingdom have adopted a framework that either features an explicit positive neutral rate for the CCyB or includes similar characteristics.

For example, the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (2022) has stated that it “supports and sees benefits in the ability of authorities to set a positive cycle-neutral CCyB rate on a voluntary basis.” For a comprehensive discussion on the merits of a positive neutral rate, see, for example, Behn et al. (2023).

Available capital headroom and profitability are key determinants of such economic costs (see above).

For a more detailed discussion, see Behn et al. (2023).

For a broader discussion on the role of BBMs and capital-based measures in real estate, see Tereanu et al. (2022); for a comprehensive analysis of the interplay between macroprudential measures, see Lo Duca et al. (2023).