How ample is macroprudential space? A simple indicator of effectively releasable buffers measuring macroprudential space.

Macroprudential capital buffers are a key tool in the regulatory framework for banks, helping to ensure a stable and resilient financial system. Macroprudential capital buffers sit on top of minimum requirements, providing an extra layer of capital. Banks can use these buffers to absorb losses in times of stress without having to recapitalise or deleverage, e.g. by cutting back lending to the real economy. While there are a range of buffers with different objectives, they are all intended to serve as shock absorbers for banks, thus contributing to the resilience of the financial system. One differentiating feature between the different buffers is that some of them can be released by authorities – e.g. the Countercyclical Capital Buffer (CCyB) or the Systemic Risk Buffer (SyRB) – while others are meant to be kept stable over the course of the financial cycle, including the Capital Conservation Buffer (CCoB) and buffers for global or other systemically important institutions, (G-SIIs/O-SIIs).[1]

In order to fulfil their objectives, buffers must be usable to absorb losses in times of stress, but experience shows that banks may be either unwilling or unable to fully utilise their buffer range. Generally, two sorts of obstacles to buffer usability have been observed.[2] First, banks tend to be unwilling to use their non-released capital buffers, because operating within the buffer range implies a breach of the Maximum Distributable Amount (MDA)[3] threshold which comes with negative consequences such as restrictions on paying out profits or associated market stigma effects, which banks may want to avoid. Such unwillingness to use capital buffers was observed, for instance, during the COVID-19 episode.[4] Second, it has been found that banks are sometimes also unable to fully use their capital buffers as doing so could result in breaching other parallel applicable minimum requirements, such as the leverage ratio or the minimum requirement for own funds and eligible liabilities (MREL).[5] This may be the case in particular for banks with lower risk-weights, for which the leverage ratio provides an effective backstop, in line with its distinct policy objective.[6]

More macroprudential space through a higher amount of releasable capital buffers can help mitigate some concerns about buffer usability. Following a release of capital buffers, banks can operate with lower capital ratios without breaching the MDA threshold. This mitigates obstacles to buffer usability arising from market stigma or distribution restrictions.[7] Lessons learnt from the pandemic are consistent with this assertion and have intensified a discussion on creating more macroprudential space through more releasable buffers. As a result, authorities in the banking union have recently been actively implementing releasable buffers.[8] While this is a very welcome development that certainly helps to enhance the effectiveness of the framework, concerns about banks’ ability to fully use a released buffer may nevertheless persist because of parallel requirements, as explained above.

A comprehensive measure of effective macroprudential space through more releasable buffers needs to account for banks potentially being unable to fully use capital freed up by a buffer release. This focus article proposes a simple and broad quantitative indicator to measure effective macroprudential space.[9] Specifically, the indicator calculates the nominal amount of risk-based capital buffers that authorities can release and that banks can use without breaching parallel minimum requirements. It can thus be understood as a measure of effectively releasable capital buffers, expressed as a percentage of banks’ risk-weighted assets.[10]

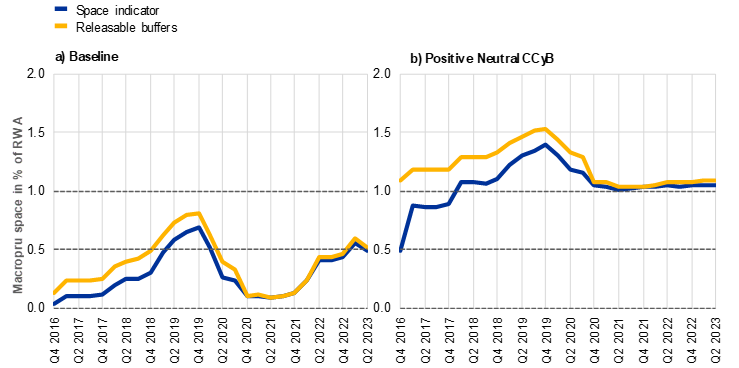

Chart A

Releasable capital buffers and the indicator of macroprudential space through effectively releasable buffers

A comparison in different scenarios

(releasable buffers in % of risk-weighted assets)

Source: Supervisory data, Buffer Usability Simulation Tool (USIT).

Notes: The macroprudential space indicator (blue line) is defined as the nominal amount of effective releasable buffers (buffer usability of both CCyB and SyRB with regard to the leverage ratio) as a percentage of risk-weighted assets (RWA), which is the basis for the application of the risk-based capital requirements. The yellow line shows the average (institution-specific) amount of CCyB and SyRB as a percentage of RWA available. The right-hand chart shows how the baseline outcome would change if a 1% positive neutral CCyB was introduced. Thus the figure illustrates that it would be possible to use this indicator to monitor macroprudential space and to assess policy options. It should be noted that the usability of releasable buffers is very bipolar at the bank level, with banks either able to fully use their releasable buffers, or not able to use them at all.

The evolution of the proposed indicator illustrates that parallel requirements matter when assessing the available macroprudential space. The left-hand figure in Chart A above highlights that macroprudential space would have been overestimated if assessed only based on the amount of releasable capital buffers.[11] The proposed indicator of effective macroprudential space is lower in all observed periods.[12] On average, before the pandemic (2016 Q3-2019 Q4), effectively releasable buffers were 10 basis points lower than overall releasable buffers. A positive neutral CCyB of 1% is one of the options to enhance macroprudential space discussed in ECB (2022). If such a CCyB had been in place during the above-mentioned pre-pandemic period, the overall amount of releasable buffers – and therefore banks’ resilience – would have increased. However, the discrepancy between total and effectively releasable buffers would have been greater in absolute terms (on average 22 basis points, as shown in Chart A, right-hand panel).[13]

Going forward, the proposed indicator of effectively releasable capital buffers can help to inform related policy discussions and may be enhanced further. The indicator is useful for authorities wishing to assess the extent to which the macroprudential capital buffers in place are effectively releasable and hence can have the intended effect. It can also help to inform broader policy discussions on further increasing macroprudential space[14] or addressing overlaps in requirements.[15] The indicator will be easy to compute: the ECB makes the tools for its calculation available to the European Systemic Risk Board (ESRB) community by means of an updated version of the USIT toolkit.[16] Going forward, further extension of the indicator may be considered, e.g. to also consider the effects of MREL, depending on data availability.[17]

Importantly, this focus article only considers constraints on effective macroprudential space stemming from the application of the leverage ratio. In practice, there are also other factors that can constrain the full use of capital released under the risk-based framework. For example, banks generally wish to maintain a safety margin on top of minimum requirements. The safety margin tends to increase in more challenging macro-financial conditions and thus has the potential to trigger procyclical adjustments by banks.[18] In addition, market pressure, fear of rating downgrades, or anticipation of future buffer reinstatement may constrain banks’ willingness to accept a decline in capital ratios, particularly when they are already at lower levels.[19] Thus, even the measure of effectively releasable buffers presented in this article may still overestimate the amount of effectively available macroprudential space. Authorities may wish to take this account when deciding on the calibration of releasable buffers.

References

Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (2021), “Early lessons from the Covid-19 pandemic on the Basel reforms”, Bank for International Settlements.

Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (2022), “Buffer usability and cyclicality in the Basel framework”, Bank for International Settlements.

Behn, M.; Rancoita, E. and Rodriguez d’Acri, C. (2020), “Macroprudential capital buffers – objectives and usability”, Macroprudential Bulletin, ECB, October.

Behn, M.; Pereira, A.; Pirovano, M.; Testa, A. (2023), “A positive neutral rate for the countercyclical capital buffer – state of play in the banking union”, Macroprudential Bulletin, ECB, April.

Berrospide, J.M., Gupta, A. and Seay, M.P. (2021), “Un-used Bank Capital Buffers and Credit Supply Shocks at SMEs during the Pandemic”, Finance and Economics Discussion Series, No 2021-043, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, Washington.

Couaillier, C. (2021), “What are banks’ actual capital targets” Working Paper Series, No 2618, ECB, Frankfurt am Main, December.

Couaillier, C., Lo Duca, M., Reghezza, A. and Rodriguez d’Acri, C. (2022a), “Caution: do not cross! Capital buffers and lending in Covid-19 times”, Working Paper Series, No 2644, ECB, Frankfurt am Main, February.

Couaillier, C., Reghezza, A., Rodriguez D’Acri, C. and Scopelliti, A. (2022b), “How to release capital requirements during a pandemic? Evidence for euro area banks”, Working Paper Series, No 2720, ECB, Frankfurt am Main, September.

De Bosio, R., Loiacono, G. (2023) “Measures of banks’ capital buffer usability under prudential and resolution requirements in the Banking Union”, Working Paper Series, No 2, Single Resolution Board.

European Central Bank (2022), “ECB’s reply to the Commission Call for Advice on the Macroprudential review”, Annex 2.

European Systemic Risk Board (2021), “Report of the Analytical Task Force on the overlap between capital buffers and minimum requirements”.

Leitner, G.; Magi, A.; Dvořák M.; Zsámboki, B (2023): “How usable are capital buffers? An empirical analysis of the interaction between capital buffers and leverage ratio since 2016” Occasional Paper Series, No 329, ECB, Frankfurt am Main, September.

Further information on the elements of the buffer framework, and their objectives can be obtained from the “ESRB handbook on operationalizing macroprudential policy”.

See Behn et al. (2020), “Macroprudential capital buffers – objectives and usability”, Macroprudential Bulletin, Article No 11, for an early discussion.

The Maximum Distributable Amount (MDA) threshold is crossed when banks dip into their combined buffer requirements. As soon as the MDA threshold is crossed, different capital conservation measures (e.g. restrictions on distributions) apply to banks.

See, for instance, Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (2021), Berrospide et al. (2021), Couaillier et al. (2022a), and Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (2022).

The capital requirements framework for banks is multidimensional. Macroprudential capital buffers are part of the risk-based capital framework, where required capital depends on the risk profile of banks’ activities. In parallel, banks also need to meet non-risk-based leverage and resolution requirements. The same item of capital may be used multiple times across these frameworks, which is why banks might not be able to fully use their capital buffers without simultaneously breaching the leverage ratio or MREL. For the purpose of this analysis, the indicator takes into account the interaction with the leverage ratio framework. The analysis can be extended to cover MREL, subject to data availability.

See, for instance, European Systemic Risk Board (2021), “Report of the Analytical Task Force on the overlap between capital buffers and minimum requirements” and Leitner et al. (2023), “How usable are capital buffers?”, Occasional Paper Series, No 329, ECB. Leitner et al. found buffer usability to be constrained due to the leverage ratio, especially for banks with on average lower risk weights.

Indeed, Couaillier et al. (2022b) provide evidence from the pandemic that is consistent with reduced buffer usability concerns following capital relief measures. See Couaillier et al. (2022b), “Caution: do not cross! Capital buffers and lending in Covid-19 times”, Working Paper Series, No 2644, ECB.

For an overview of the current state of play see, for example, Behn et al. (2023), “A positive neutral rate for the countercyclical capital buffer – state of play in the banking union”. Lessons learnt from the pandemic and possible policy implications are discussed in ECB (2022), “Annex 2: Enhancing macroprudential space in the banking union – Report from the Drafting Team of the Steering Committee of the Macroprudential Forum”, Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (2021), and Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (2022).

In line with the discussion in ECB (2022), “Annex 2: Enhancing macroprudential space in the banking union – Report from the Drafting Team of the Steering Committee of the Macroprudential Forum”, we refer to macroprudential space as the amount of releasable capital buffers. Therefore, the proposed indicator can be understood as quantifying effective macroprudential space as the share of effectively releasable capital buffers.

Since effective releasability of buffers can only be determined at the bank level, the indicator is first calculated on a bank-by-bank basis and then aggregated by using risk-weighted assets as a weight. The assessment of the effective releasability is done by means of USIT, which follows the methodology for calculating the usability of capital buffers set out in ESRB (2021), “Report of the Analytical Task Force on the overlap between capital buffers and minimum requirements”.

As further discussed below, even the measure of effectively releasable buffers may still overestimate the amount of effectively available macroprudential space.

The difference between the two measures is less pronounced in the post-pandemic period, mainly because buffer usability increased for some large banks. This was partly because of the gradual phasing-in of various buffer requirements. For more details, see Leitner et al. (2023), “How usable are capital buffers?”, Occasional Paper Series, No 329, ECB.

The discrepancy between the two lines depends on the share of banks for which the leverage ratio is relatively more binding than the risk-based framework. With a positive neutral rate for the CCyB, a larger set of banks would be subjected to a releasable buffer (i.e. all banks). Since the leverage ratio is relatively more binding for a greater fraction of banks in this extended set, it implies a greater wedge between the two lines.

See for instance ECB (2022), “Annex 2: Enhancing macroprudential space in the banking union – Report from the Drafting Team of the Steering Committee of the Macroprudential Forum”.

See for instance ESRB (2021), “Report of the Analytical Task Force on the overlap between capital buffers and minimum requirements”.

The buffer usability simulation tool (USIT) makes it possible to calculate the amount of capital buffers that cannot be used without breaching parallel requirements at the bank level, based on supervisory data. It was developed by the ESRB task force on capital buffer usability. For a description of USIT see Box 3 of ESRB (2021), “Report of the Analytical Task Force on the overlap between capital buffers and minimum requirements”.

For a recent assessment of buffer usability constraints stemming from MREL, see De Bosio and Loiacono (2023), “Measures of banks’ capital buffer usability under prudential and resolution requirements in the Banking Union”, Working Paper Series, No 2, SRB.

See, for example, Couaillier (2021), “What are banks' actual capital targets?”, Working Paper Series, No 2618, ECB, or Couallier et al (2022a), “Caution: do not cross! Capital buffers and lending in Covid-19 times”, Working Paper Series, No 2644, ECB.

See Behn et al. (2020), “Macroprudential capital buffers – objectives and usability”, Macroprudential Bulletin, ECB, October.