Opening remarks by Fabio Panetta, Member of the Executive Board of the ECB, at the joint workshop of European independent fiscal institutions and the European System of Central Banks on “European fiscal policy and governance reform in uncertain times”

Frankfurt am Main, 20 September 2023

Our fiscal framework is at a crossroads.[1] Negotiations on the European Commission’s legislative proposals for reform of the EU’s economic governance rules are entering a crucial phase.

To ensure this reform is successful and that it strengthens our economic governance, the new framework will have to protect us from the mistakes of the past. And it will need to make it possible to use again policies that have proven to be effective.

Before the pandemic, we had accumulated a significant public investment gap that had undermined our economic potential.[2] Fiscal policy had often been procyclical. And macroeconomic policies had at times worked against each other. We have paid a high price for this in the form of weaker growth, higher unemployment and deteriorating fiscal conditions.

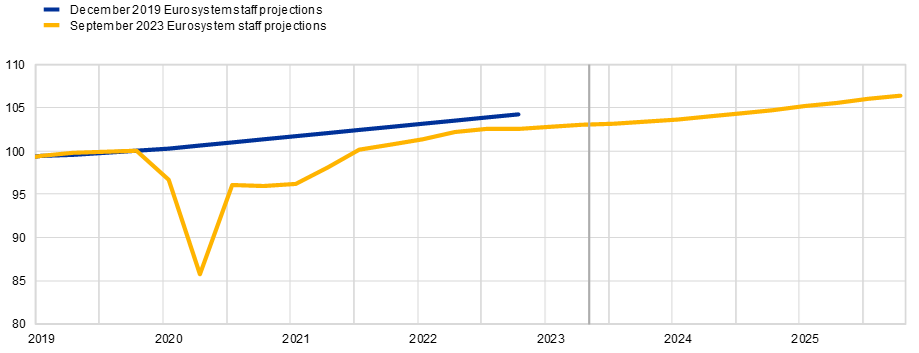

But the response to the pandemic was different. National fiscal policies responded countercyclically to the downturn, complemented by a European stimulus plan which focused on investments in the green transition and digitalisation. This fiscal response worked in tandem with monetary policy and supervisory measures, mitigating financial amplification effects and pulling the economy out of the liquidity trap.[3] The result has been an almost full recovery (Chart 1), record-low unemployment and the return of debt to a downwards path after the initial increase recorded in 2020.

Chart 1

Euro area real GDP

(chain-linked volumes, Q4 2019 = 100)

Sources: ECB, Eurosystem staff macroeconomic projections for the euro area (BMPE), December 2019 BMPE, ECB staff macroeconomic projections for the euro area (MPE), September 2023 MPE, and ECB staff calculations.

Notes: Data are seasonally and working day-adjusted. Historical data may differ from the latest Eurostat publications due to data releases after the projections cut-off date. The vertical line indicates the start of the current projection round.

More recently, fiscal policy has complemented monetary policy to counter the inflationary effects of Russia’s war against Ukraine and the energy crisis.

Today I will argue that we need to embed the lessons learned from this experience in our fiscal governance.

Ensuring the sustainability of public finances is like balancing a seesaw, with debt on one side and growth on the other. To achieve a true balance, fiscal policy must be countercyclical, consistent with price stability and supportive of potential growth. It must also be based on measures that are both economically sound and politically sustainable. This means not only ensuring that fiscal policy is based on rigorous technical analysis – where independent fiscal institutions (IFIs) have an important role to play – but also that it has broad political support and is democratically accountable.

I will argue that this balance must be based on three elements.

First, I will emphasise the importance of complementarity between monetary and fiscal policies and the fact that the nature of their interactions depends on the state of the economy. In times of stress, a combination of unconventional fiscal and monetary policies may well prove to be the best course of action.

I will then argue for a fiscal framework which takes into account the importance of both debt and economic growth for the sustainability of public finances. We need an integrated approach that delivers the right mix of fiscal prudence, smart public investments and structural reforms.

Finally, I will focus on two key aspects of the debate for reforming European fiscal governance: the role of IFIs and the missing elements of this reform. We need to strengthen the “E” in EMU, our Economic and Monetary Union. This cannot be achieved without a well-coordinated fiscal stance and a permanent central fiscal capacity in the euro area.

Ensuring complementarity between fiscal policy and monetary policy

Let me begin by stressing the importance of the interaction between fiscal policy and monetary policy. The nature of this interaction depends on the state of the economy.

Monetary-fiscal interactions since 2020

Since 2020, in just three and a half years, there have been four identifiable distinct phases.

In the first one, fiscal policy and monetary policies worked in tandem to support our economies in response to the shock caused by the pandemic, which had resulted in sudden disruptions on both the demand and the supply side. National fiscal policies were strongly expansionary, introducing measures such as short-time work schemes, to mitigate the impact of the pandemic. At the same time, monetary policy ensured that favourable financing conditions were maintained to safeguard the transmission of monetary policy. Non-standard monetary and fiscal measures, such as the ECB’s pandemic emergency purchase programme and the EU’s Next Generation EU programme, played a central role in restoring confidence, especially in vulnerable euro area economies.

In a second and shorter phase, after the summer of 2021 the focus shifted to ensuring the correct sequencing of policy normalisation after the pandemic. In European fora, it was argued that fiscal normalisation should come first, albeit in a gradual and growth-friendly manner. This would have put the economy on a trajectory that would also have allowed for the gradual normalisation of monetary policy, thereby fostering a balanced and sustainable recovery.

However, Russia’s aggression of Ukraine and manipulation of energy supplies[4] dramatically changed the economic landscape once again, leading to the third phase. Given the sharp rise in energy prices and the emergence of supply bottlenecks, inflation unexpectedly rose to levels not seen since the early 1980s and economic growth forecasts fell. This triggered a different response from monetary and fiscal authorities.

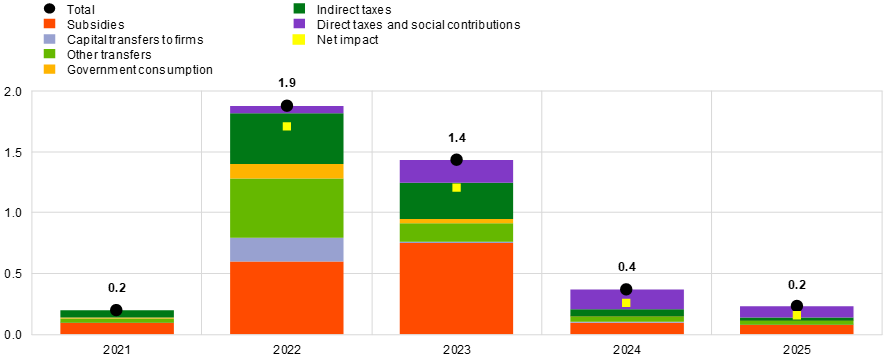

The striking aspect of this phase was the unconventional nature of the fiscal measures adopted. While the ECB intensified its efforts to fight inflation, euro area countries implemented temporary fiscal measures to alleviate the burden of high energy prices (Chart 2). More than half of these measures had a direct negative impact on the cost of energy consumption. This helped to contain inflation, and thus contributed to wage moderation. The remaining measures supported household and corporate incomes in ways that were often insufficiently targeted at the most vulnerable ones.

Chart 2

Energy and inflation-related fiscal support measures in the euro area

(percentage of GDP)

Sources: ECB, ECB staff macroeconomic projections for the euro area (MPE), September 2023 MPE, and ECB staff calculations.

Notes: The bars show the energy and inflation fiscal compensatory measures in terms of gross budget impact. The yellow dots show the net budget impact (gross support minus discretionary financing measures).

In this phase, the ECB avoided unwarranted increases in sovereign spreads through its decision to introduce the Transmission Protection Instrument (TPI) in July 2022. The TPI allowed the ECB to adjust its monetary stance quickly without causing financial fragmentation, which would have hampered the effective transmission of monetary policy across the euro area. The TPI also enhanced the ability of Member States, particularly those with high debt ratios, to counteract the energy shock.[5]

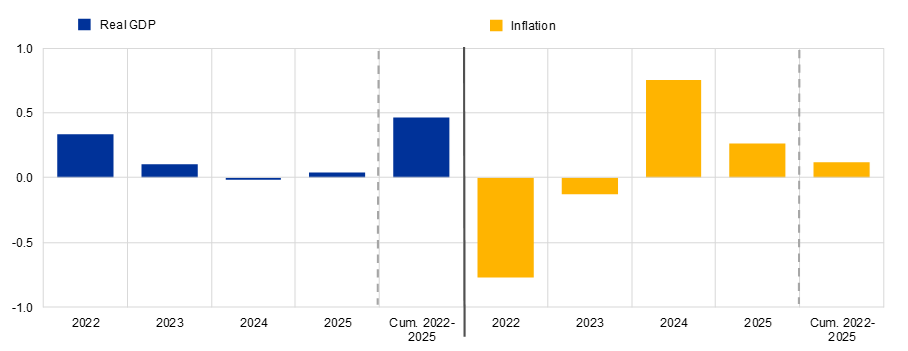

ECB staff simulations suggest that unconventional fiscal policies (UFPs) contributed to containing inflation by 0.9 percentage points over the period 2022-23 (Chart 3).[6] Additional estimates based on microsimulation models[7] indicate that the impact of these measures may have been even larger – inflation up to 1.6 percentage points lower for the euro area in 2022 alone.[8] Importantly, UFPs have helped to avoid second-round effects and keep long-term inflation expectations anchored, thereby supporting monetary policy in reducing euro area inflation from a peak of 10.6% in October 2022 to 5.2% today.[9] UFPs have also helped to maintain a balanced economic environment[10] and stabilise the European economy.[11]

Chart 3

Estimated impact on real GDP and HICP inflation of fiscal support in the euro area

(percentage points)

Source: ECB staff simulations.

Notes: Simulation based on the June 2023 Eurosystem staff macroeconomic projections for the euro area. Results show deviations form a counterfactual scenario of no fiscal policy support, and include judgement as needed to better reflect uncertainty around model estimates, especially with respect to energy price caps. Results based on the Eurosystem Working Group on Forecasting’s structured questionnaire. HICP stands for Harmonised Index of Consumer Prices.

As we navigate our way through 2023, the fall in energy prices has created new policy challenges, representing the fourth phase. During this phase it has become necessary to withdraw fiscal energy support measures in a timely manner. Failure to do so could create a demand impulse that would exacerbate inflationary pressures, which would in turn trigger a monetary policy response. This would be highly inefficient, akin to giving with one hand and taking away with the other.[12]

Lessons learned

The recent interactions between monetary policy and fiscal policy provide two important lessons. First, monetary policy and fiscal policies can and should work together when necessary, such as in response to large shocks. In recent years this has been essential to underpin economic resilience, bolster the recovery and fight inflation.

Indeed, price stability and fiscal sustainability support each other. Prudent fiscal policies in good times create the necessary space for fiscal policy to support demand alongside monetary policy during economic downturns. At the same time, a genuinely anti-inflationary monetary policy and price stability are necessary to maintain the sustainability of public finances. In fact, in the decade before the pandemic, low inflation allowed European countries to continue to borrow at low cost, even though their debt ratios rose sharply. This changed with the onset of the adverse global supply shocks, which pushed up both inflation and financing costs (Chart 4).

Chart 4

Debt level, cost of borrowing and inflation in the euro area

(left-hand scale: percentage of GDP, right-hand scale: percentage points)

Sources: Eurostat and ECB staff calculations.

Note: Yield refers to the euro area 10-year government benchmark bond yield. The latest observations are for the first quarter of 2023 for debt and the second quarter of 2023 for yield and HICP.

For this interaction to work effectively in the future, we need to ensure that the euro area’s fiscal stance is not simply an incidental outcome of national fiscal policies. Instead, it should be achieved through the effective coordination of Member States’ fiscal policies under the guidance of the European Commission and with an enhanced role for the European Fiscal Board during the assessment phase.

The second lesson is that the monetary-fiscal interaction should not follow rigid, predetermined rules. Both the economic literature and the experience of policymaking suggest that this interaction should depend on the state of the economy, which can only be taken into account by introducing sufficient flexibility into our fiscal governance. This is the case, for example, when we allow escape clauses that temporarily freeze the implementation of European fiscal rules to be activated in exceptional circumstances.

What does this mean in practice for macroeconomic stabilisation in EMU?

Under normal economic conditions, countercyclical fiscal policy should continue to rely primarily on national automatic stabilisers, especially in the euro area, where they are widely used.[13] This reflects the fact that automatic stabilisers are better suited than discretionary measures to respond to the normal fluctuations of the business cycle because of their timeliness, predictability, proper targeting and sustainability.[14]

But this is not the whole story. In exceptional circumstances – when “tail events” occur – countercyclical discretionary fiscal measures play an important role in the presence of low inflation traps or inflationary spirals, thereby supporting price stability without infringing on central bank independence.[15]

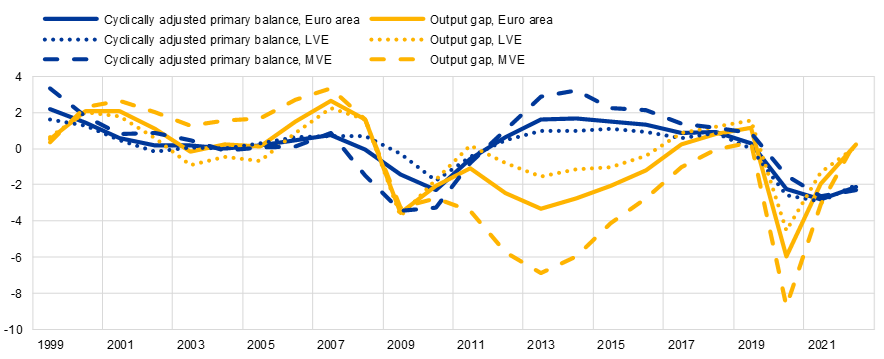

The different fiscal policies followed in the euro area during past crises are a good illustration of this point. During the great financial crisis and the pandemic, fiscal policy across the EU had a decisive countercyclical effect, bringing the cyclically adjusted primary balance to a deficit of around 2% of euro area GDP (Chart 5). This response limited the severity of the downturn and helped the economy to recover. The sovereign debt crisis of 2012-13 provides a counterexample. Fiscal policy at the time was procyclical. The cyclically adjusted primary surplus rose to around 2% of GDP, deepening and prolonging the recession. The tightening was particularly strong in the most stressed euro area economies, which experienced significant output losses.

Chart 5

Fiscal policy stance and business cycle in the euro area

(percentage of GDP)

Sources: ECB staff calculations based on the European Commission’s Spring 2023 Economic Forecast.

Notes: The euro area aggregate shown in this chart comprises the 12 original member countries. LVE stands for less vulnerable economies, which comprise Belgium, Germany, France, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Austria and Finland. MVE stands for more vulnerable economies, which include Ireland, Greece, Spain, Italy and Portugal. This distinction aims to highlight the different macroeconomic dynamics that these two “groups” have shown over the lifespan of the monetary union. The distinction involves some simplification.

Macroeconomic simulations suggest that if a consistently countercyclical fiscal policy for the euro area had been maintained over time, fiscal buffers could have been built up in the good times (e.g. before the great financial crisis) that would have helped to cushion the second downturn during the sovereign debt crisis.[16]

Ongoing review of the fiscal governance framework

What does all this mean for the fiscal governance framework?

Above all, the fiscal framework must reflect the fact that the sustainability of public finances depends on both the numerator and the denominator of the debt-to-GDP ratio. We need to pay close attention to debt dynamics, but this would be useless without growth.

In my view, the fiscal framework should have four main characteristics.

First, it must provide for a realistic, gradual and sustained adjustment of public debt ratios in order to strengthen sustainability and rebuild fiscal space ahead of future downturns. This has become even more crucial since the pandemic, which led to higher and more heterogeneous debt ratios across countries.

Second, fiscal policy should be genuinely countercyclical, both in responding to adverse economic shocks and in rebuilding buffers once the economy is back on track.

Third, the proposed framework should ensure that Member States can formulate their own strategies to achieve the objectives of reducing debt and deficits. And to facilitate effective implementation, it should be simple and provide robust, stable growth projections.

Any common safeguards aimed at striking the right balance between a country-by-country approach and common quantitative benchmarks should not undermine the proposed rationale of the framework or add undue complexity. We need to move away from a “one-size-fits-all” strategy to strengthen ownership and accountability at the national level.

Finally, effective fiscal governance should support the EU’s growth potential. The pursuit of fiscal sustainability should be accompanied by adequate incentives for investment and reform in order to strengthen our Union and prepare it for the future.

We must not sacrifice much-needed investment, which has been too low for too long,[17] with detrimental longer-term effects. This has also been a by-product of a fiscal framework that was not designed to protect investment, where fiscal consolidation was often pursued by cutting public investment.[18] Even in highly efficient economies, low public investment and the associated private investment gap have eroded competitiveness over time, jeopardising future growth.[19]

A comprehensive approach that integrates these elements promises to be both economically viable and politically palatable. And, as I will argue, it could also shape the evolution of our fiscal framework after the current economic governance review has been concluded, as we transition out of the Next Generation EU programme.

In my view, the Commission’s proposals balance these four essential components of optimal fiscal governance when compared with the previous rules.

The ECB expressed its support for the legislative package in an official opinion published in July this year.[20] We made specific, technical suggestions to refine the new framework. A sound, transparent and credible new fiscal governance will be crucial to anchor market expectations for debt sustainability and sustainable, inclusive growth.

Let me now turn to two specific aspects of the ECB’s opinion.

Role of independent fiscal institutions in EU fiscal governance

I would like to start with the role of national IFIs, whose work is generally recognised as having a positive impact on fiscal policy (Figure 1).

Overall, the ECB supports the proposal to strengthen the role of IFIs in the fiscal framework (Figure 2). While fiscal policy is the prerogative of democratically elected governments and cannot be delegated to technical institutions, it should still be based on sound economic analysis.

This is primarily the role of IFIs, which can contribute significantly to improving fiscal governance in the EU.[22] In particular, IFIs can help to improve the quality of public spending and facilitate its reallocation to investment projects.

The ECB has expressed support for the Commission’s proposals on IFIs. We welcome the inclusion of the “comply-or-explain” principle in the legislation and agree that IFIs should have adequate own resources to carry out their mandates effectively.

The contribution of IFIs could be further enhanced by giving them an advisory role in the preparation of national fiscal plans. IFIs could assess the underlying assumptions, consistency of the plans with the Commission’s technical trajectory for public debt, and the reform and investment commitments. This would reinforce national ownership.

We also support the European Fiscal Board contributing significantly to economic governance at the EU level. This could include an enhanced role in assessing the appropriate fiscal stance of the euro area as well as the need to activate or extend the general escape clause of the Stability and Growth Pact.

Figure 2

National IFIs, the European Fiscal Board and EU Governance

Missing elements in the EU fiscal governance framework

My second key takeaway from the ECB opinion relates to a conspicuous absence from the proposed new economic governance framework: the euro area dimension.

As I have previously argued, this pertains to the need for an enhanced framework to monitor and steer the aggregate fiscal stance of the euro area, which is a fundamental requirement for smooth monetary-fiscal interactions in our region.

But this also concerns, crucially, completing EMU through the establishment of a properly designed permanent central fiscal capacity (CFC).

Without the establishment of a CFC, euro area governance will remain incomplete – a view shared by policymakers, institutions and academics.[23] As I have argued elsewhere,[24] it is an illusion that EMU can function smoothly without a centralised fiscal capacity. It is now time to address the imbalances in the institutional framework of the monetary union, whereby a single monetary policy coexists with a fiscal policy that is fragmented across national lines.

Moreover, without a permanent common fiscal capacity with a borrowing function, balancing fiscal sustainability, stabilising public finances and addressing Europe’s substantial investment needs will be impossible. The weakness of public investment in the euro area, particularly in the years following the great financial crisis, is a case in point (Chart 6).

Chart 6

Euro area real GDP growth, real public investment growth and crisis episodes

(year-on-year growth in percentage points; real public investment as a percentage of GDP)

Sources: ECB, Eurosystem staff macroeconomic projections for the euro area (BMPE), June 2023 BMPE, and ECB staff calculations.

Note: Year-on-year change in euro area real public investment calculated as percentage of three-year-moving average real GDP.

The establishment of a CFC is also crucial to gain fiscal credibility, which requires common rules and spending by the centre. The debate on this issue is still in its early stages, and more analysis is needed on the relationship between fiscal rules and the CFC.[25]

In my view, a CFC should have three main objectives. First, to achieve effective macroeconomic stabilisation. Second, to support public investment at the national level, with positive spillovers for all. And third, to enable investment in common public goods that benefit the entire European economy and promote a healthy strategic autonomy. These public goods include investments in the green and digital transitions, common defence and energy security, migration policies, and the development of new technological infrastructure in innovative sectors.[26]

Such a capacity is essential to improve our fiscal governance.

A permanent stabilisation function would ensure that investment is not compromised during economic downturns, thus preventing pro-cyclicality and supporting capital accumulation without sacrificing future prosperity.

In addition, managing centralised investment projects at the European level could generate economies of scale, promote positive externalities and raise productivity across the bloc.

Let me give a concrete example of the potential economic benefits of a CFC: the financing of joint military research and development (R&D) spending and innovative investments in defence capabilities.[27]

In today’s geopolitical environment, military spending in EU countries is widely expected to rise to the NATO commitment of 2% of GDP, and even higher in some countries (Chart 7). This additional, significant fiscal burden could crowd out other productive investments.

Chart 7

Defence expenditure in 2021 and announced spending targets

(percentage of GDP)

Sources: Category 2 in COFOG data (Eurostat, OECD, IMF).

Notes: *denotes countries that are not members of NATO. Announced spending targets are based on media reports from October 2022. Spending targets can be subject to frequent revisions.

At the same time, ECB research shows that the efficiency of military spending in the EU lags behind that of other global players. This reflects the fragmentation of the military procurement system and the fact that EU countries spend relatively more on personnel than on R&D, which would produce much higher fiscal multipliers.

Recent research concludes that a CFC aimed at financing military expenditure would support long-term productivity if it shifted resources away from personnel compensation, which currently accounts for the bulk of national defence expenditure, towards financing projects such as investments in capital infrastructure and R&D.[28]

As a central banker, I do not comment on the defence policy of EU Member States. However, one thing is clear: from an economic perspective, the external security of the EU is a European public good. There is therefore a strong economic case for a CFC to finance joint spending on R&D and defence capabilities.

Whatever the ultimate goals of a permanent CFC, its funding through common EU borrowing would contribute to the creation of a European safe asset, with important benefits for the functioning of our financial system. Indeed, a European risk-free benchmark rate would allow for the homogeneous development and pricing of risky assets across the euro area, facilitating diversification, the availability of pan-European collateral and the expansion of activities typical of advanced capital markets.[29] This would be a decisive step towards the creation of a genuine capital markets union, which is an essential element for the efficient allocation of resources and the financing of the real economy.

Conclusion

Let me conclude.

Ensuring the long-term sustainability of public finances requires addressing both components of the debt-to-GDP ratio. Fiscal policy should be countercyclical in order to smooth economic fluctuations, while fostering public investment to support potential growth.

And for fiscal policies to contribute to both price and macro-financial stability, they need to complement monetary policy when needed. Price stability, in turn, supports fiscal sustainability by keeping government financing costs low over time.

To be successful and deliver both fiscal sustainability and growth, the fiscal governance reform must reflect the lessons learned from the past and provide the necessary safeguards by protecting investment, incentivising reform, ensuring national ownership and providing a simple and stable framework.

But we also need to address the missing elements of the proposed reform. Moving from fiscal governance to fiscal union requires a permanent central fiscal capacity. This is necessary to complement national fiscal policies and achieve the appropriate fiscal stance for the euro area.

A European fiscal capacity is essential to finance the common investments that are key to maintaining and expanding Europe’s economic potential. Without it, we will not be able to meet the financing needs, reap the economies of scale and trigger the private investment needed to drive Europe’s energy transition, digital transformation and security architecture. We need to start thinking now about what comes after Next Generation EU, or risk taking a step back instead of forward.

Sound fiscal governance is a cornerstone of the European project. We all have a role to play, and I am confident that today’s workshop will enrich and advance the debate.

Thank you for your attention.

I would like to thank Krzysztof Bańkowski, Ettore Dorrucci, Donata Faccia, Maximilian Freier, Ellinor Olsson Kaalhus, Daniel Kapp, Francesca Vinci and Jean-Francois Jamet for their help in preparing this speech.

See Panetta, F. (2022), “Investing in Europe’s future: The case for a rethink”, speech at Istituto per gli Studi di Politica Internazionale (ISPI), 11 November.

See Panetta, F. (2021), “Monetary-fiscal interactions on the way out of the crisis”, keynote speech at the Conference of the Governors of Mediterranean Central Banks on “Central banks at the frontline of the COVID-19 crisis: weathering the storm, spurring the recovery”, 28 June.

See Panetta, F. (2022), “Greener and cheaper: could the transition away from fossil fuels generate a divine coincidence?”, speech at the Italian Banking Association, 16 November.

ECB (2022), The Transmission Protection Instrument, 21 July. See also Panetta, F. (2022), “Normalising monetary policy in non-normal times”, speech at a policy lecture hosted by the SAFE Policy Centre at Goethe University and the Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR), 25 May; and Lagarde, C. (2022), “Ensuring price stability”, The ECB Blog, 23 July.

The “unconventional fiscal policies” referred to here are the discretionary fiscal measures taken in response to the recent energy price crisis and consequent surge in inflation. They include measures to cap the increase in energy and food prices (“price measures”) and measures to support household or firm income (“income measures”). Overall, evidence shows that these measures tend to result in a better smoothing of inflation over time.

Amores, A. F., Basso, H.S., Bischl, S., De Agostini, P., De Poli, S., Dicarlo, E., Flevotomou, M., Freier, M., Maier, S., García-Miralles, E., Pidkuyko, M., Ricci, M. and Riscado, S. (2023), “Inflation, fiscal policy and inequality: The distributional impact of fiscal measures to compensate consumer inflation”, Occasional Paper, ECB, forthcoming.

Similarly, the IMF has estimated that UFPs reduced euro area inflation by 1 to 2 percentage points in 2022-2023. See Chi Dao, M., Dizioli, A., Jackson, C., Gourinchas, P-O and Leigh, D. (2023), “Unconventional fiscal policies in times of high inflation”, Working Papers, IMF, September.

Eurostat (2023), “August 2023 – Annual inflation down to 5.2% in the euro area”, euroindicators, No 105/2023, 19 September.

See footnote 7 for more details. See also Bańkowski, K. et al. (2023), “Fiscal policy and high inflation”, Economic Bulletin, ECB, Issue 2; Checherita-Westphal, C. and Dorrucci, E. (2023) “Update on euro area fiscal policy responses to the energy crisis and high inflation”, Economic Bulletin, ECB, Issue 2; and Blanchard, O. and Pisani-Ferry, J. (2022), “Fiscal support and monetary vigilance: Economic policy implications of the Russia-Ukraine war for the European Union”, Policy Briefs, No 22-5, Peterson Institute for International Economics, April.

As argued by IMF staff, the success of UFPs in Europe may have been due to specific conditions, such as the temporary nature of the energy shock and the type of inflation experienced. Compared with the United States, where inflation was mainly driven by core components in the context of an overheating domestic economy, the high inflation in the euro area largely reflected supply side shocks and a gradual pass-through of the rise in energy prices to core inflation. The measures adopted in Europe would probably have been counterproductive in the United States. See Chi Dao, M. et al. (2023), op. cit.

See Panetta, F. (2023), “Monetary policy after the energy shock”, speech at an event organised by the Centre for European Reform, the Delegation of the European Union to the United Kingdom and the ECB Representative Office in London, 16 February.

It has been estimated that national budgets in the euro area could provide as much stabilisation of asymmetric shocks as the US federal budget. See ECB (2020), “Automatic fiscal stabilisers in the euro area and the COVID-19 crisis”, Economic Bulletin, Issue 6.

See in ‘t Veld, J., Larch, M. and Vandeweyer, M. (2012), “Automatic Fiscal Stabilisers: What they are and what they do”, Economic Papers, No 452, European Commission, Brussels, April; and Crespo Cuaresma, J., Reitschuler, G. and Silgoner, M. (2011), “On the effectiveness and limits of fiscal stabilizers”, Applied Economics, Vol. 43, No 9, pp. 1079-1086.

This has been illustrated in studies like Del Negro, M. and Sims, C.A. (2015), “When does a central bank’s balance sheet require fiscal support?”, Journal of Monetary Economics, Vol. 73, pp. 1-19 and Maćkowiak, B., and Schmidt, S. (2023), “Passive monetary policy and active fiscal policy in a monetary union”, Discussion Paper, No 17034, CEPR, March. Interestingly, these “tail events” have been so frequent over the past 15 years that the term “exceptional” seems almost a misnomer.

Bańkowski, K. (2023), “Fiscal policy in the semi-structural model ECB-BASE”, Working Paper Series, No 2802, ECB, Frankfurt am Main, March.

See Panetta, F. (2022), “Investing in Europe’s future: The case for a rethink”, op. cit.

The legislative proposals put forward by the European Commission in April 2023 aim to protect investment by allowing for more gradual fiscal adjustment paths (up to a maximum of seven years, instead of four) when an EU Member State commits to a set of investments and reforms that comply with well-defined criteria. Previously, it had also been proposed to decompose public debt into a fast and a slow-speed portion of adjustment, with the latter applying to debt accumulated from financing public investment and expenditures that contribute to European public goods (labelled “spending for the future”). See D’Amico, L., Giavazzi, F., Guerrieri, V., Lorenzoni, G. and Weymuller, C.-H. (2022), “Revising the European fiscal framework, part 1: Rules”, VoxEU Column, VoxEU-CEPR, 14 January.

Germany’s public investment gap vis-à-vis its AAA-rated peers from 2008 to 2021 has been estimated at around 12% of GDP (calculated by comparing Germany’s cumulative net public fixed capital formation as a percentage of GDP with the average for AAA-rated peers since the global financial crisis in 2008). See Scope Ratings (2021), Germany’s investment gap widens to EUR 410bn, 12% of GDP, threatening to harm competitiveness, 19 July. See also Fratzscher, M. (2018), “The investment gap”, The German Illusion, Oxford University Press, pp. 73-94; and Wolff, G.B. and Roth, A. (2018), “Understanding (the lack of) German public investment”, Bruegel Blog, 19 June.

See Opinion of the European Central Bank of 5 July 2023 on a proposal for economic governance reform in the Union (CON/2023/20) (OJ C 290, 18.8.2023, p. 17).

See Căpraru, B. et al. (2022), “Do independent fiscal institutions cause better fiscal outcomes in the European Union?“ ; IMF (2013), “The Functions and Impact of Fiscal Councils” ; OECD (2020), “Independent fiscal institutions: Promoting transparency and accountability early in the COVID-19 crisis” ; OECD (2011), “How Can Fiscal Councils Strengthen Fiscal Performance?” ; EFB (2022), “2022 annual report of the European Fiscal Board” ; Gorčák, M. and Šaroch, S. (2021), “Impact of fiscal institutions on public finances in the European Union: Review of evidence in the empirical literature”.

For example, empirical evidence underlines their contribution to reducing the dispersion of forecasts and thus improving fiscal stability. See Nerlich, C., and Reuter, W. H. (2013), “The design of national fiscal frameworks and their budgetary impact”, Working Paper Series, No 1588, ECB, September.

The seminal contribution was provided by Kenen, P. (1969), “The Theory of Optimum Currency Areas: An Eclectic View,” in Mundell, R. and Swoboda, A., (eds.), Monetary Problems of the International Economy, The University of Chicago Press, pp. 41-60. See also, among others, Beetsma, R., Cimadomo, J. and van Spronsen, J. (2022), “One Scheme Fits All: a central fiscal capacity for the EMU targeting eurozone, national and regional Shocks”, Discussion Paper, No 16829, CEPR, February; Beetsma, R., Cima, S. and Cimadomo, J. (2018), “A minimal moral hazard central stabilisation capacity for the EMU based on world trade”, Working Paper Series, No 2137, ECB, Frankfurt am Main, March; Arnold, N.G. et al. (2022), “Reforming the EU Fiscal Framework: Strengthening the Fiscal Rules and Institutions”, Departmental Papers, No 2022/014, IMF, September; and Arnold, N.G., Barkbu, B.B., Ture, H. E., Wang, H. and Yao, J. (2018), “A Central Fiscal Stabilization Capacity for the Euro Area”, Staff Discussion Notes, No 18/03, IMF, March.

See Panetta, F. (2022), “Europe’s shared destiny, economics and the law”, Lectio Magistralis on the occasion of the conferral of an honorary degree in Law by the University of Cassino and Southern Lazio, 6 April.

In the words of Mario Draghi, “(…) we need to acknowledge that truly credible fiscal rules cannot work without an equivalent re-thinking of where fiscal powers should reside. As automatic rules represent a devolution of powers to the centre, they can only work if they are matched by a greater degree of spending from the centre.” See Draghi, M. (2023), “The Next Flight of the Bumblebee: The Path to Common Fiscal Policy in the Eurozone”, 15th Annual Martin Feldstein Lecture, NBER, 11 July.

For a discussion on European public goods, see Panetta, F. (2023), “Investing in Europe’s future: The case for a rethink”, op. cit.

In a previous speech I elaborated on a CFC for the green transition (see Panetta, F. (2023), “Investing in Europe’s future: The case for a rethink”, op. cit.).

See Freier, M., Ioannou, D. and Vergara Caffarelli, F. (2023), “EU public goods and military spending”, The EU’s Open Strategic Autonomy from a central banking perspective – Challenges to the monetary policy landscape from a changing geopolitical environment, Occasional Paper Series, No 311, ECB, Frankfurt am Main, March, pp. 144-153.

See Panetta, F. (2023) “Europe needs to think bigger to build its capital markets union”, The ECB Blog, 30 August. This is not to deny that there are limits to how far a CFC can be financed today, not least because the borrowing costs of the EU are still higher than those of its strongest members. This calls for exploring the complementary avenue of enhancing the EU-specific tax base.

Ευρωπαϊκή Κεντρική Τράπεζα

Γενική Διεύθυνση Επικοινωνίας

- Sonnemannstrasse 20

- 60314 Frankfurt am Main, Germany

- +49 69 1344 7455

- media@ecb.europa.eu

Η αναπαραγωγή επιτρέπεται εφόσον γίνεται αναφορά στην πηγή.

Εκπρόσωποι Τύπου-

20 September 2023