- SPEECH

Mind the gap(s): monetary policy and the way out of the pandemic

Speech by Fabio Panetta, Member of the Executive Board of the ECB, at an online event organised by Bocconi University

Milan, 2 March 2021

It is a great pleasure to be back at Bocconi and share with you my views on the current economic situation.

The year ahead will present macroeconomic policymakers with critical choices.

In 2020, with the pandemic raging, the direction of policy support was obvious and the choices facing policymakers were relatively narrow. Monetary and fiscal authorities everywhere intervened to support the economy on a massive scale.

But in 2021, with the progress made on vaccine technology, policy choices have become less clear-cut. We face a situation in which the end of the pandemic emergency is in sight and an incipient recovery is on the horizon. As such, it might be tempting to conclude that there is less need for monetary policy support.

But I will argue today that this temptation must be resisted. In fact, 2021 is still a “pandemic year”. And even if the pandemic ends soon, its economic consequences will not.

We will still face two prominent gaps that we need to close: the output gap and the inflation gap. And if we fail to do so with sufficient force – by being too hesitant in providing the necessary degree of policy support or withdrawing it too quickly – we could inadvertently hold back economic growth and depress inflation for years to come.

So, we will in fact need ample policy support for as long as necessary to emerge stronger from the crisis and limit long-term damage. At present, the risks of providing too little policy support still far outweigh the risks of providing too much.

By keeping nominal yields low for longer, we can provide a strong anchor to preserve accommodative financing conditions. Improvements in the outlook will then work in our favour through lower real rates, further supporting confidence in a sustained return of inflation to our aim.

Eliminating downside risks

There is undoubtedly some good news today. Across advanced economies, vaccination programmes are ongoing; the second phase of lockdowns has been less costly than the first; the manufacturing sector continues to show resilience, buoyed by global demand. And the US administration is providing renewed support to multilateralism.

In the EU, national and European authorities are working towards a swift implementation of the Next Generation EU (NGEU) programme, while political tensions in individual Member States have receded and commitment to growth-enhancing reforms within a European framework is rising. There is a good chance that a recovery will take hold in the latter part of this year.

But that is not a justification for policies to run on neutral. There are in fact two imperatives which call for further policy support.

First, in a dramatic crisis like this one, macroeconomic policymakers should not bank on the most favourable scenario materialising. Their role is to ensure that the worst scenarios are ruled out. As I have argued elsewhere, the pandemic has produced an asymmetric balance of risks, which requires an asymmetric reaction function.[1]

This is true of the inflation outlook, where the risk of inflation undershooting our 2% aim is still very high, while the risk of overshooting is negligible. Our December projections had inflation reaching just 1.4% in 2023 and core inflation reaching just 1.2%.[2]

While inflation is expected to rise this year, it will be driven by one-off statistical effects linked to the composition of the consumption basket, as well as base effects following on from previous energy price falls and the unwinding of the VAT cut in Germany. The increase will therefore be temporary. Just as we looked though temporary negative inflation in recent months, we will look through this transitory hump in inflation.

The near-term growth outlook is also skewed downward. Economic activity is projected to recover only gradually and return to its pre-pandemic level in the course of 2022. And this shallow growth path remains vulnerable to a series of downside risks.

The slow rollout of vaccines in the euro area and the spread of new variants of the virus are delaying the full reopening of the economy. This delay – and the uncertainty around it – is likely to depress consumer and investor sentiment.

We are likely to see higher cyclical divergence from the United States, where the recovery will be further supported by significant fiscal stimulus in 2021. This divergence will bring risks of its own: in fact, we are already seeing undesirable contagion from rising US yields into the euro area yield curve. If unaddressed, this would lead to a tightening of financing conditions that is inconsistent with our domestic outlook and inimical to our recovery.

How strong the rebound will be, once the economy can finally reopen, also remains unclear. While we can expect a temporary surge in spending on goods, research suggests that pent-up demand tends to be weaker for services,[3] spending on which has been more compressed.

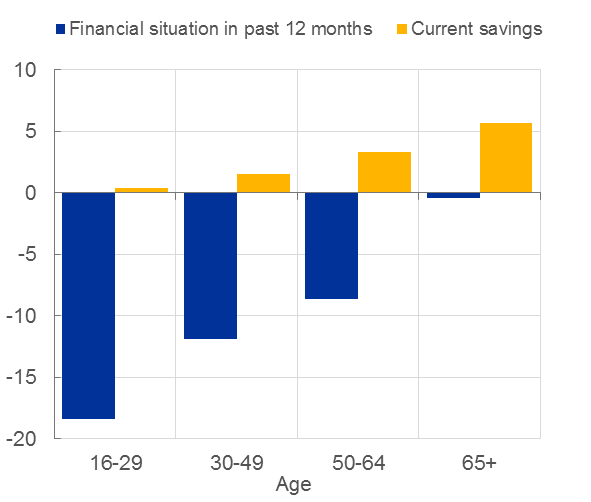

Besides, the distribution of income across households still points to a high saving rate, at least throughout 2021. Younger households have been drawing more on their savings as their situation has worsened, whereas older households have been setting aside more (Chart 1). As older, wealthier households tend to have a lower marginal propensity to consume, these distributional issues imply that overall spending is likely to remain compressed even after social distancing measures have been relaxed.

In addition, we still cannot predict when the sectors worst hit by the crisis – such as tourism or travel – will return to normality, especially with more infectious variants of the virus spreading. The risks to private consumption growth are therefore substantial.

Chart 1 Household financial situation and savings

(change in percentage balance from January 2020 to February 2021)

Sources: European Commission and ECB staff calculations.

Nor should we overly rely on investment to boost growth, at least not in the near term. Given the weak financial starting point of many firms, investment is likely to only increase gradually and cautiously.[4] It might also be affected by a catch-up in corporate insolvencies.[5]

A risk management approach would therefore clearly call for policy to eliminate these risks and reinforce the central growth path. And, if we were to do “too much” and push the economy onto a stronger growth path, that would in fact be a welcome result. This brings me to the second reason why further support is needed.

Closing the gaps faster

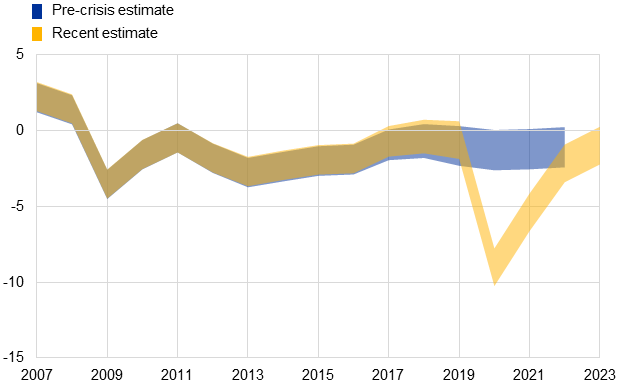

Conditional on our December projections, the output gap in the euro area will not close before 2023, and will slowly narrow with output converging gradually towards potential rather than exceeding it (Chart 2). But the experience of the last cycle suggests that it is hard to lift inflation dynamics without demand testing potential more dynamically. Despite several years of robust economic growth, the euro area economy might still have been operating with significant economic slack even on the eve of the pandemic.

Chart 2 Pre-crisis and recent estimates of the output gap in the euro area

(% of potential output)

Source: ECB staff calculations.

Notes: Shaded areas indicate interval estimates based on an unobserved components model (UCM) by Tóth (2021), representing an uncertainty band of plus/minus two standard deviations around the point estimate. The blue area represents the UCM projection conditional on the December 2019 Eurosystem staff projections, while the yellow area represents the UCM projection conditional on the December 2020 Eurosystem staff projections. See Tóth, M. (2021), “A multivariate unobserved components model to estimate potential output in the euro area: a production function based approach”, Working Paper Series, No 2523, ECB, February.

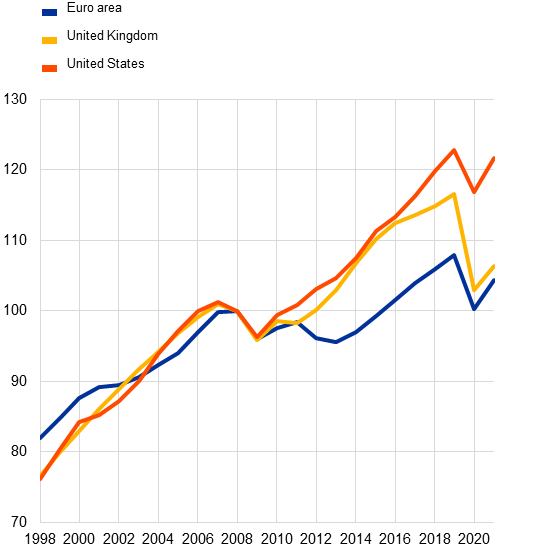

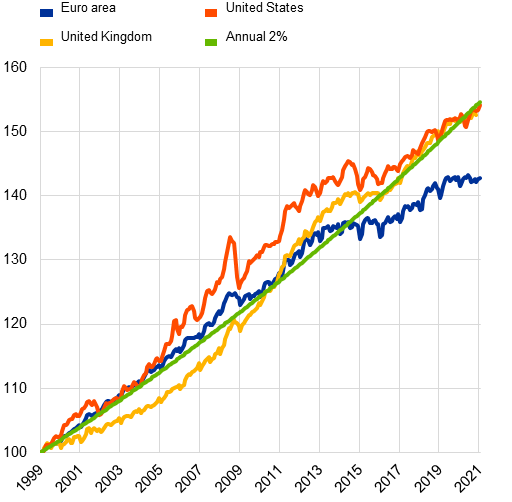

A key reason for this was that domestic demand growth had previously been too weak for too long, which in turn allowed inflation expectations to drift down and weaken underlying dynamics. In the decade after the Lehman crash, yearly domestic demand growth in the euro area was almost 2 percentage points lower on average than it had been in the previous decade, and it was much lower than that of our main trading partners (Chart 3). This contributed to compressing inflation persistently below our aim, leading to a significant price level gap (Chart 4).[6] That was not the case in the United States or the United Kingdom, where domestic demand stayed on a stronger trajectory.

Chart 3 Domestic demand

(Index: 2008 = 100)

Source: AMECO.

Chart 4 Harmonised Index of Consumer Prices (HICP)

(all-items, January 1999=100)

Source: Eurostat.

The upshot is that, if we were to remain on the growth and inflation trajectory we projected in December, we would lose several more years in the convergence of inflation towards our aim and risk further negatively affecting inflation expectations. This clearly called for action, as reflected in the additional support we decided on in December.

Boosting demand is also necessary to reduce hysteresis risks after the pandemic. The pandemic may well have caused scarring, especially for low-skilled workers.[7] Lower business innovation and investment might also have scarred productivity.[8]

Policy should not accept hysteresis as a reality which imposes new supply constraints, but rather explicitly set out to test those constraints.

What we saw in the latter stages of the post-2008 recovery seems to suggest that a high-pressure economy helps re-absorb lower-skilled workers into the labour market, because it induces companies to train people themselves.[9] A tight job market also improves the outlook for future demand, thereby strengthening business investment.

Delivering the necessary policy stance

So the challenge we face is how to deliver the necessary policy stance.

Since the start of the pandemic, monetary policy in the euro area has gone through three phases. In the first phase – the phase of fragmentation – the flexibility of our pandemic emergency purchase programme (PEPP)[10] averted an unjustified widening of spreads which would have disrupted monetary policy transmission. As a result, speculators stopped using short positions on particular euro area sovereigns as a way of expressing their negative views on the global economy.

In the second phase, the PEPP increasingly became a tool for steering the overall monetary policy stance. Its size and duration became the key parameters for loosening financing conditions and pushing down the euro area yield curve to the low levels observed last December. In parallel, our targeted longer-term refinancing operations (TLTROs) successfully pinned down bank lending rates to some of the lowest levels on record.

We have now entered a third phase, in which we need to preserve accommodative financing conditions to support the recovery and the convergence of inflation to our aim. This essentially means more focus on anchoring key financial variables – above all, lending rates and the yield curve – as key indicators of the monetary policy stance.

This approach should progressively add accommodation because, as actual and expected inflation pick up, anchoring nominal yields allows real yields to fall. And there should be no doubt that lower real yields would provide welcome additional stimulus, given how far we are from full capacity and the subdued level of current and expected inflation.[11]

Implementing such a policy requires the central bank to broadly identify what level of nominal yields it is aiming to achieve; to tailor its purchases to achieve that level; and to be ready to intervene to the extent necessary. In December, when we recalibrated the PEPP, the Governing Council determined that the financing conditions prevailing at that time were favourable. So, that constellation of financing conditions should be seen as the reference point for our policy moving forward.

By that metric, the steepening in the nominal GDP-weighted yield curve we have been seeing is unwelcome and must be resisted.

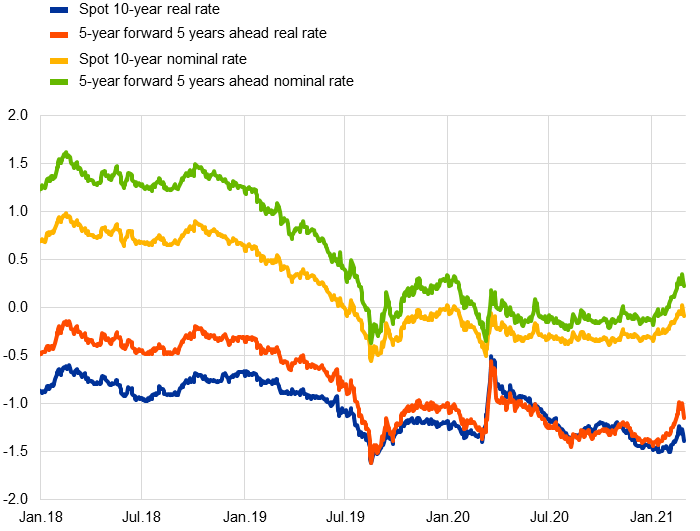

Amid the increase in market yields (Chart 5)[12], President Lagarde recently stated that “the ECB is closely monitoring the evolution of longer-term nominal bond yields.”[13] In the past week, euro area yields across the maturity spectrum, including risk-free rates, have remained well above the levels seen at the start of this year.

Chart 5 Euro area real and nominal rates

Source: Bloomberg.

So we should not hesitate to increase the volume of purchases and to spend the entire PEPP envelope or more if needed. In this way, we can prevent a tightening of financing conditions which would otherwise lead to inflation remaining below our aim for longer.

Eventually, firm commitment to steering the euro area yield curve may allow us to slow the pace of our purchases. But in order to reach that point, we must establish the credibility of our strategy by demonstrating that unwarranted tightening will not be tolerated.

From policy fatalism to policy coordination

We should be confident about what we can achieve.

It is sometimes claimed that monetary policy may be ineffective against global disinflationary forces or can only raise inflation at the cost of intolerable side effects, and that as a result it should not push too hard to achieve its goal and instead extend its policy horizon far into the future.

But counterfactual analysis shows that after the financial crisis and during the COVID-19 shock the ECB’s expansionary policies have been highly effective. Without our policies, inflation and GDP growth would have been dramatically lower and many more people would have lost their jobs.

In fact, it is failure to make full use of monetary policy in the face of falling demand and inflation expectations – rather than its supposed lack of effectiveness – that would trap us in an environment of low inflation, subdued growth and high unemployment.

Preserving favourable financing conditions will have a powerful effect on demand and inflation. However, given the fall of the natural rate of interest,[14] monetary policy is more effective if deployed in sync with other policies. Monetary, fiscal and structural policies must reinforce each other in order to cut slack and close the gap between saving and investment.

So far, Europe has taken the right direction.

NGEU provides us with an opportunity, for the first time ever, to achieve genuine European fiscal stabilisation backed by common debt issuance.

The ECB will continue net purchases under the PEPP until at least the end of March 2022. Moreover, we expect net purchases under our asset purchase programme to continue and policy rates to stay at present or lower levels until inflation has robustly converged to our aim and this has been consistently reflected in underlying inflation dynamics.

The commitment to preserve favourable financing conditions for a lengthy period sends a clear signal to governments not to underspend relative to the scale of the shock, or withdraw fiscal stimulus too early, out of fear that borrowing costs will tighten prematurely. Fiscal policies continue to be a key channel for transmitting monetary policy to the real economy[15] and they are expected to remain supportive in 2021.

We need to maintain this momentum.

If NGEU-led investment and national reforms lift potential growth, while demand policies remain expansionary until supply constraints appear, we could generate significantly higher employment, investment and confidence in Europe – and possibly even recover some of the potential that we lost in the aftermath of the last crisis.

As a rough illustration, if we were able to return to the potential growth trend that we believed was possible only 13 years ago – in 2008 – we would be able to increase output by 14% today without overheating the economy (Chart 6).

Chart 6 Euro area real and potential GDP

(EUR billions)

Source: AMECO.

Member States – in particular those with high debt and productivity challenges – need to implement reforms that remove obstacles to doing business and encourage resources to flow to the most productive firms. They need to target investment in technology, education and infrastructure, creating an environment that bolsters growth and supports the sustainability of debt.

We have a joint interest in making the European economy more dynamic.[16] NGEU is an important tool precisely because it ensures that common spending triggers growth-enhancing reforms that subsequently benefit all. If Member States seize this opportunity and show commitment to reform, the resulting benefits for all citizens of the EU can pave the way for a further Europeanisation of both fiscal and structural policies by building on the instruments developed during the pandemic.[17]

Conclusion

My main message today can be summed up with the title of a song by the electronic music duo Daft Punk[18]: “Harder, better, faster, stronger.”

The harder we push to close the output and inflation gaps, the better the outlook for the euro area economy. And the faster we get there, the stronger our growth potential will be.

Achieving this will require the right combination of monetary and fiscal support at the EU level, and it will require continued, determined reforms at the national level.

It will also require perseverance. We will need to keep going until we see inflation sustainably reaching 2%, in an environment of robust growth and rising employment. For these reasons, policy support will have to remain in place well beyond the end of the pandemic.

- Panetta, F. (2020), “Asymmetric risks, asymmetric reaction: monetary policy in the pandemic”, speech at the meeting of the ECB Money Market Contact Group, 22 September.

- ECB (2020), “Eurosystem staff macroeconomic projections for the euro area”, December.

- Beraja, M. and Wolf, C. (2021), “Demand Composition and the Strength of Recoveries”, mimeo.

- According to a recent EIB survey, some 45% of European firms expect to reduce investment in 2021, while only 6% intend to increase it. EIB (2021), “Investment Report 2020/2021: Building a smart and green Europe in the COVID-19 era”; see also Panetta, F. (2020), “A commitment to the recovery”, speech at the Rome Investment Forum 2020, 14 December.

- IMF analysis of a sample of 13 advanced economies spanning 1990 to the COVID-19 crisis finds that, unlike in past recessions, bankruptcies has actually fallen during this recession by about 30%. See IMF (2021), “World Economic Outlook Update”, January.

- Chart 4 shows Eurostat’s HICP index for comparability across jurisdictions (including Eurostat’s proxy-HICP for the United States). The Federal Reserve’s target measure is inflation in the price index for personal consumption expenditures (PCE).

- In the euro area, the share of low-skilled workers in employment fell by 6% up to third quarter of last year, while the share of high-skilled workers rose by 3%.

- Bloom, N., Bunn, P., Mizen, P., Smietanka, P. and Thwaites, G. (2020), “The Impact of Covid-19 on Productivity”, NBER Working Paper, No 28233, December.

- In 2013, the European Commission estimated that structural unemployment (measured by the non-accelerating wage rate of unemployment (NAWRU)) in the euro area would rise to 11.6% in 2015, owing in part to supposed skill mismatch. In 2019, after several years of strong demand growth, that rate was estimated at 7.8%.

- A key feature of the PEPP is the ability to differentiate purchases across jurisdictions depending on market conditions.

- In December the Eurosystem staff projected inflation to be, even in the benign scenario, well below our aim at the end of the horizon.

- In recent weeks both nominal and real long-term rates have increased. The five-year forward five years ahead real rate is now close to its December 2019 level.

- Lagarde, C. (2021), “Investing in our climate, social and economic resilience: What are the main policy priorities?”, speech at the opening plenary session of the European Parliamentary Week 2021, 22 February.

- Estimates for the natural rate in the euro area have dropped from between 0.6% and 2.2% on average from 1999 to 2011, to between -1.3% and 0.5% thereafter. See Brand, C., Bielecki, M. and Penalver, A. (2018), “The natural rate of interest: estimates, drivers and the challenges to monetary policy”, Occasional Paper Series, No 217, ECB, Frankfurt am Main, December.

- Panetta, F. (2020), “A commitment to the recovery”, speech at the Rome Investment Forum 2020, 14 December.

- Panetta, F. (2020), “Why we all need a joint European fiscal response”, contribution published by Politico, 21 April.

- See Guttenberg, L., Hemker, J. and Tordoir, S. (2021), “Everything will be different: How the pandemic is changing EU economic governance”, Jacques Delors Centre Policy Brief, 11 February.

- Daft Punk, who are considered by some as the most influential pop musicians of the 21st century, announced last week that they were splitting up after 28 years. See Petridis, A. (2021), “Daft Punk were the most influential pop musicians of the 21st century”, The Guardian, 23 February; and Hsu, H. (2021), “Daft Punk Brought Us to the Dance Floor”, The New Yorker, 26 February.

European Central Bank

Directorate General Communications

- Sonnemannstrasse 20

- 60314 Frankfurt am Main, Germany

- +49 69 1344 7455

- media@ecb.europa.eu

Reproduction is permitted provided that the source is acknowledged.

Media contacts