- SPEECH

The compass of monetary policy: favourable financing conditions

Speech by Philip R. Lane, Member of the Executive Board of the ECB, at Comissão do Mercado de Valores Mobiliários

25 February 2021

Introduction

Over the last year, the pandemic has presented a series of challenges to central banks. In addition to the initial task of stabilising markets, the scale and duration of the shock to the world economy and the global financial system has required extensive monetary accommodation.[1] Looking ahead, it is clear that the successful containment of the virus and the fostering of a sustainable recovery will require an extended period of favourable financing conditions for all sectors of the economy.

In my remarks today, I will set out some considerations for thinking about favourable financing conditions as the compass guiding monetary policy.

The structure of this speech is as follows. First, I will explain the logic of employing the favourability of financing conditions as the compass for monetary policy. In assessing financing conditions, it is desirable to adopt a holistic approach, based on a multi-faceted set of indicators for both bank-based and market-based financing conditions. Accordingly, in the following sections, I next turn to the analysis of bank-based funding conditions, which is followed by the analysis of market-based financing conditions. In the final part of the speech, I summarise the overall theme of this speech and place the current pandemic challenge in the context of the overall campaign to deliver our inflation aim in the medium term.

Favourable financing conditions as the compass

The phrase “favourable financing conditions” intentionally puts the spotlight on a pivotal section of the transmission mechanism that links the basic monetary policy instruments controlled by central banks (policy rates, asset purchases and refinancing operations) to the ultimate objective of delivering the medium-term inflation aim. Under pandemic conditions, two threats to the efficiency of monetary policy can be clearly identified. First, frictions in financial intermediation may disrupt the transmission of monetary policy impulses to the financing conditions for key economic actors (households, firms and governments).[2] Second, in the absence of clear forward guidance from central banks in relation to future monetary policy decisions, high uncertainty about the path of the virus and the robustness of the post-pandemic recovery may make these economic actors reluctant to commit to significant spending decisions.

In this context, a focus on preserving favourable financing conditions as the compass guiding monetary policy addresses both concerns. First, it emphasises that the central bank is committed to recalibrating its underlying policy instruments if it detects any threat to the favourability of financing conditions. Second, clear communication that the financing conditions directly relevant to households, firms and governments will remain favourable during the pandemic period reduces uncertainty and bolsters confidence, thereby encouraging spending and investment, and ultimately underpinning the economic recovery and inflation.

In terms of the price stability mandate, the pandemic shock poses ongoing risks to the projected path of inflation. In December 2019, the Eurosystem staff macroeconomic projections for the euro area had forecast progress over the period 2020-2022, with inflation set to climb from 1.0 per cent in 2019 to 1.6 per cent in 2022. It looks like inflation will have averaged 0.3 per cent in 2020, while our December 2020 staff projections forecast inflation of 1.0 per cent, 1.1 per cent and 1.4 per cent in 2021, 2022 and 2023 respectively (Chart 1).

Chart 1

Realised and projected HICP inflation

(year-on-year percentage changes, quarterly averages)

Sources: Eurosystem staff macroeconomic projections and Eurostat.

Notes: The chart shows quarterly averages of year-on-year percentage changes in HICP inflation, except for the first quarter of 2021, which shows realised inflation in January 2021. The latest observations are for January 2021 for realised inflation, for the fourth quarter of 2022 for the December 2019 projections and for the fourth quarter of 2023 for the December 2020 projections.

The negative impact of the pandemic on the projected inflation path reflects the extraordinary scale of the disruption to economic activity, with annual output in the euro area declining by 6.8 per cent in 2020. While the containment of the virus should trigger a significant expansion later this year that will also extend into 2022, it is clear that significant policy interventions will be required both to support the workers and firms that have been damaged by the pandemic and to underpin a sustainable post-pandemic recovery. In turn, vigorous inflation dynamics are only likely if the overall economic recovery is robust. This macroeconomic assessment provides the basic rationale that preserving favourable financing conditions is a necessary intermediate target for countering the negative pandemic shock to the projected inflation path, which in turn is a pre-condition for delivering the medium-term inflation aim of the ECB.

The preservation of favourable financing conditions for an extended period of time helps to support inflation developments through multiple channels.[3] First, the commitment to preserving favourable financing conditions reduces financing uncertainty for banks, corporates, households and governments alike. Second, the assurance to maintain favourable financing conditions will help to prevent an undue tightening of financing conditions in a situation of an improving macroeconomic landscape, as markets factor in the reaction of the ECB. Keeping favourable financing conditions in this environment could even accelerate the dynamics of the recovery, since better economic prospects combined with attractive financing conditions can fast-track consumption and investment. Finally, an extended period of favourable financing conditions will underpin confidence in the recovery and in the eventual pick-up in inflation, which will support inflation expectations and thereby provide additional monetary stimulus through lower real rates. Overall, preserving favourable financing conditions can help to counter the negative pandemic shock to the inflation path and thereby support the achievement of the price stability objective via a reduction in uncertainty and through stronger forward guidance about how the central bank might respond to a future tightening in financing conditions that is inconsistent with countering the negative pandemic shock to the projected inflation path.

In delivering favourable financing conditions during the pandemic, the pandemic emergency purchase programme (PEPP) and the easing of conditions for the targeted longer-term refinancing operations (TLTRO) programme have been the two cornerstones of our monetary policy response: their design and calibration are directly linked to the evolution of the pandemic and its impact on financing conditions and the economic outlook.[4] In particular, in December, the Governing Council pledged that purchases under the PEPP will be conducted to preserve favourable financing conditions over the pandemic period.

In assessing the financing conditions required to counter the negative pandemic shock to the projected inflation path, it is essential to employ a holistic and multi-faceted approach and examine financing conditions for the whole economy. Holistic conveys that a broad spectrum of indicators covering the entire transmission chain should be monitored. Multi-faceted means that we should adopt a granular approach, such that each indicator provides a valuable signal on a specific segment of the transmission process.

Overall, we need to assess indicators that provide information on the whole gamut of transmission – from upstream stages to downstream effects. The upstream stages are steered by the risk-free and sovereign yield curves. In addition to the direct relevance of these measures for the governments and firms that obtain funding in the bond markets, developments in these indicators ultimately have downstream effects on bank-based intermediation. I will begin from the downstream effects, where financing conditions are defined by the cost and volume of external finance available to the firms and households that are dependent on banks for access to credit. I will then analyse the upstream stages of the monetary transmission mechanism.

Naturally, the focus on credit conditions in the banking system on the one side and the bond markets on the other side is consistent with the main methods used by central banks in steering financing conditions, namely through the various types of operations with banking system counterparties and through outright securities purchases which primarily focus on bond markets. Other financial indicators also feed into the staff macroeconomic projections and are incorporated into the Governing Council’s regular assessments of the appropriate monetary stance.

Bank-based financing conditions

In the euro area, banks are the major providers of credit for households and firms. This is especially the case for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs): over the past decade, 43 per cent of the external finance for euro area SMEs has come from banks.[5]

The pandemic and the measures to contain the spread of the virus have severely disrupted economic activity and curtailed business revenues. The avoidance of adverse feedback loops between the real economy and financial markets is a central task for policy makers. A tightening in funding costs or worsening liquidity positions have so far been forestalled by the prompt policy reaction from monetary, supervisory and fiscal authorities. In turn, banks have been able and willing to meet the strong demand for liquidity over the course of the pandemic. In the face of lower and more uncertain incoming revenues, the demand for credit to bridge the downturn and finance the recovery sharply increased in 2020: in the euro area, the annual growth rate of loans to firms more than doubled from 3.0 per cent in February 2020 to 7.3 per cent in May 2020.

Bank lending to firms moderated during the summer and autumn months as containment measures were eased and as firms had by then built up substantial liquidity buffers. In fact, liquidity buffers of firms helped to prevent a resurgence in emergency borrowing towards the end of the year, despite the renewed increase in COVID-19 infections.

The euro area bank lending survey (BLS) confirms that high loan demand of firms was accommodated by banks, which met the demand for bridge financing despite the rapid worsening of economic prospects in the second quarter of 2020. Over this period, credit standards on loans to both large firms and SMEs remained broadly unchanged or tightened only moderately. Monetary, supervisory and fiscal policies have been central to supporting bank lending conditions since the onset of the pandemic in terms of volumes and lending rates, which are around historically low levels for both firms and households.

On the monetary policy front, the ECB’s targeted longer-term refinancing operations (TLTRO III) – which were recalibrated in March, April and December of last year – have contributed decisively by providing attractive funding to banks under the condition of maintaining lending to the real economy.[6] The favourable impact of the TLTRO III on bank lending conditions and lending volumes has been signalled clearly by banks in the BLS.[7]

Fiscal measures have played a decisive role in warding off strong credit constraints. In addition to the beneficial impact on corporate balance sheets of the extensive fiscal support provided to workers and firms (together with other measures to relieve fixed costs), firms have also drawn on pandemic-related government-guaranteed loans, which have been typically granted at very favourable conditions. Evidence from the BLS shows that credit standards on loans with government guarantees eased considerably last year, in contrast to the tightening in overall credit standards reported mainly in the second half of 2020 (Chart 2).

Chart 2

Changes in credit standards and demand for loans to euro area firms in 2020

(net percentages of banks reporting an easing (+)/tightening (-) of credit standards and an increase (+)/decrease (-) in loan demand; net loan flows in EUR billions)

Source: ECB (BLS and BSI statistics).

Notes: Quarterly net percentage changes have been cumulated over the first and second half of 2020 respectively. The latest observations are for the fourth quarter of 2020.

In the autumn, however, signals from the BLS pointed to a broad-based tightening in credit conditions, even though bank lending rates have remained at historically favourable levels. Banks attribute the tightening of bank lending conditions to the intensification of risks to creditworthiness and the prospect of possible loan losses in the future, especially as the pandemic has lasted longer than originally expected. While Chart 3 shows that the net tightening of credit standards on loans to firms remains moderate compared with the global financial and sovereign debt crises, it signals potential risks to future loan growth. This reflects the well-established leading indicator properties of the BLS, according to which changes in credit standards on loans to euro area firms tend to lead actual lending to firms by around four to five quarters. Reinforcing these cautionary signals, the BLS also shows that the scaling back of investment plans has been an important source of the decline in credit demand over the last quarters. In a similar vein, the latest Survey on the Access to Finance of Enterprises in the euro area (SAFE) also reports that SMEs expect the availability of external and internal sources of finance to deteriorate.

Chart 3

BLS bank lending conditions and loan growth to firms

(left-hand scale: net percentages of banks reporting an easing (+)/tightening (-) of credit standards and an increase (+)/decrease (-) in loan demand; right-hand scale: percentages)

Source: ECB (BLS and BSI statistics).

Note: The latest observations are for the fourth quarter of 2020.

These risks to credit supply can be mitigated through the continuation of policy support measures by monetary, supervisory and fiscal authorities: the predictive information content of credit standards is state-contingent and the downside risks to future loan growth are less likely to materialise if the cost of funding of banks remains favourable. It follows that the evolution of corporate vulnerabilities and their possible ramifications for the bank-intermediated financing conditions facing the real economy should be closely monitored.

Above all, it remains a central task for policymakers to forestall a mutually-reinforcing adverse loop whereby, on the one side, banks perceive the dwindling loan demand as a negative signal about the state of the economy while, on the other side, firms may see their concerns about the future prospects for the macroeconomic situation confirmed by a tightening of borrowing conditions. This adverse interaction would be reinforced if household spending were to weaken and thereby were to further dampen the prospects for firms.

From a monetary policy perspective, in addition to supporting directly the downstream component of financing conditions through refinancing operations (especially TLTROs), preserving favourable market-based financing conditions also helps to safeguard favourable bank lending conditions for the real economy and thereby contain such adverse feedback dynamics. These upstream-downstream inter-connections underline the critical importance of market-based financing conditions for the entire economy, not just for those entities that directly raise funding in the capital markets.

Market-based financing conditions

The funding costs of all sectors in the economy ultimately depend on the prevailing conditions in the money and bond markets: market-based funding costs directly influence the funding costs of banks, corporates and sovereigns. Even households and small businesses which finance themselves via banks rather than in the market incur changes in their cost of funding through the impact of market-based financing conditions on bank-based financing conditions. For example, any increase in the market funding costs of banks can be passed on to borrowers in the form of higher bank lending rates. In addition, market-based financing conditions influence non-bank intermediation, since the costs and benefits to participants in this sector vary with shifts in returns on investment.

The two key yield curves in the euro area for the funding conditions of all sectors in the economy are the overnight index swap (OIS) curve – a proxy for a risk-free curve in the euro area – and the GDP-weighted sovereign bond yield curve.[8] Ensuring that the risk-free yield curve remains at highly accommodative levels is a necessary (but not sufficient) condition for ensuring that overall financing conditions are supportive enough to counter the negative pandemic shock to the projected inflation path.[9] It is also essential that changes in the risk-free curve are transmitted to those benchmark rates that matter for the pricing of financial instruments and bank credit. Sovereign bond yields act as such a benchmark in the euro area by serving as the basis for the pricing of corporate and bank bonds, as well as the pricing of bank loans to firms and households (Chart 4 and Chart 5). As such, sovereign yields are a key element in determining general financing conditions in all sectors and jurisdictions across the euro area.

Chart 4

Bank and sovereign bond yields

(daily; percentages per annum; x-axis: sovereign yields; y-axis: bank bond yields)

Sources: Markit iboxx, ECB and ECB calculations.

Notes: The chart reports the correlation between the (level of) bank bond yields and sovereign yields. Each dot corresponds to a daily recording of the average yield for senior unsecured bonds (IG) issued by banks with a given maturity in a given country and the sovereign yields with the same maturity for the same day in the same country. The latest observation is for 11 February 2021.

Chart 5

Corporate and sovereign bond yields

(daily; percentages per annum; x-axis: sovereign yields; y-axis: corporate bond yields)

Sources: Markit iboxx, ECB and ECB calculations.

Notes: The chart reports the correlation between the (level of) corporate bond yields and sovereign yields. Each dot corresponds to a daily recording of the average yield for senior unsecured bonds (IG) with a given maturity issued by non-financial corporations in a given country and the sovereign yields with the same maturity for the same day in the same country. The latest observation is for 11 February 2021.

It follows that the OIS yield curve and the GDP-weighted sovereign yield curve play fundamental roles in the transmission of monetary policy and deserve particular attention within a holistic and multi-faceted approach to monitoring financing conditions. This is especially the case because the OIS and GDP-weighted sovereign yield curves stand midway between the set of monetary policy instruments and the broader financing conditions applicable to the economy. In one direction, shifts in the OIS yield curve and the GDP-weighted sovereign yield curve are early indicators of changes in the downstream set of indicators. In the other direction, these yield curve indicators are responsive to re-calibrations of our primary monetary policy instruments.

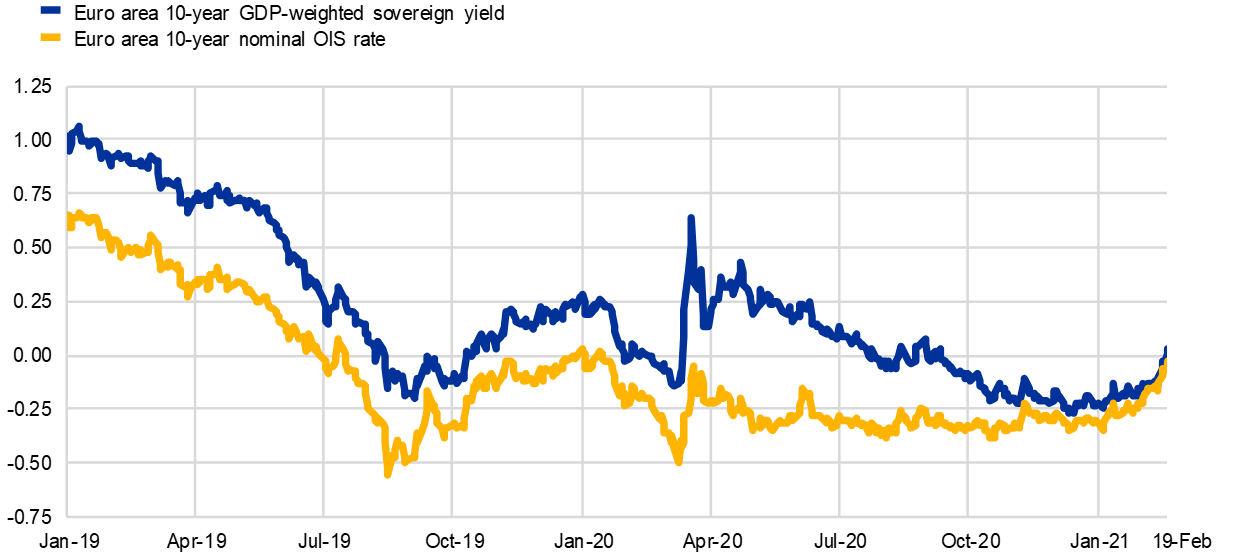

Our monetary policy measures can contribute to preserving the OIS yield curve and the GDP-weighted sovereign yield curve at favourable levels. Following a temporary disconnect at the onset of the pandemic in the spring of 2020, our monetary policy actions successfully restored a close co-movement between the OIS curve and the GDP-weighted sovereign yield curve, most notably through the market stabilisation function of the PEPP (Chart 6). In one direction, policy measures that in a first instance might primarily affect the risk-free curve also tend to move the euro area GDP-weighted yield curve in the same direction; in the other direction, policy measures that directly operate in the sovereign bond markets also shift the OIS curve indirectly. The interplay of different sets of policy measures therefore determines the wider transmission of the ECB’s monetary policy.

Chart 6

10-year GDP-weighted sovereign yield and 10-year nominal OIS rate in the euro area

(percentages per annum)

Sources: Refinitiv and ECB calculations.

Notes: The latest observations are for 19 February 2021.

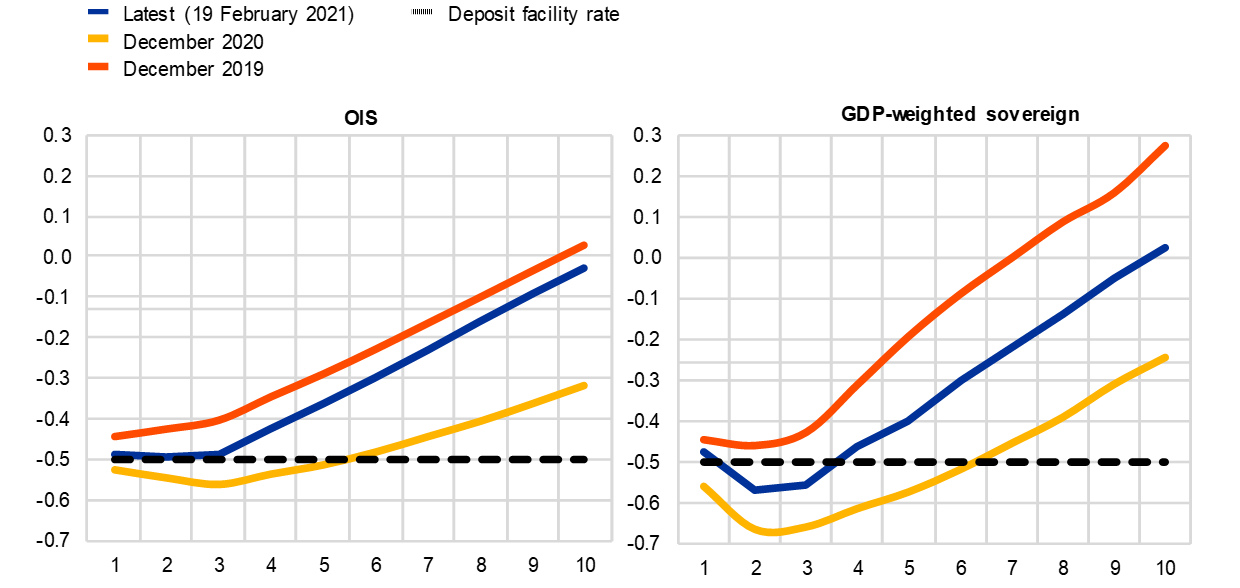

With this in mind, it is instructive to compare the current levels of these yield curves to the pre-pandemic period and to those prevailing our December monetary policy meeting. Chart 7 shows that there was a considerable lowering of the middle and long segments of these yields curves over the course of 2020. By mid-December, these curves were relatively flat compared to the short-term policy rate (the deposit facility rate). In the initial weeks of 2021, there has been a steepening of these curves.

Chart 7

Euro area risk-free OIS and GDP-weighted sovereign yield curves and the ECB’s deposit facility rate

(y-axis: percentages per annum; x-axis: maturity in years)

Sources: Refinitiv and ECB calculations.

Notes: “December 2020” refers to the day before the December 2020 Governing Council meeting (8 December 2020). “December 2019” refers to 31 December 2019.

The prevailing yield curves should be assessed in the context of ensuring that financing conditions are sufficiently favourable to counter the negative pandemic shock to the projected inflation path. This assessment will vary over time, taking into account revisions to the economic and inflation outlook. At a quarterly frequency, the staff-led macroeconomic projection exercise draws on a wide range of structural and empirical models and a large set of economic and financial indicators, while also benefiting from the collective judgement of staff experts.

In addition, as is evident from the public accounts, each monetary policy meeting is informed by comprehensive analyses of recent financial market developments and the latest macroeconomic and inflation indicators, while the contribution of our monetary policy measures to financing conditions is extensively analysed. Accordingly, the quarterly macroeconomic projections exercise and the analyses discussed in our monetary policy meetings help to inform the Governing Council’s collective assessment of the favourability of financing conditions, in the context of countering the negative pandemic shock to the projected inflation path.

Of course, in addition to the analysis of market developments as part of the cycle of regular monetary policy meetings, much can be learned at a higher frequency from the evolution of the yield curves, together with ancillary indicators such as measures of inflation compensation and other financial variables. In particular, the forward-looking nature of financial markets provides insights into the evolving views of market participants in relation to the macroeconomic and inflation outlook at various horizons, together with their risk assessments and, of course, their views regarding the monetary policy reaction functions of central banks. The integrated nature of global financial markets also means that there are clear spillovers across different currency areas in terms of the underlying shocks driving bond yields. Such financial spillovers are especially consequential if economies are at different stages of the economic cycle.

For any given level of nominal interest rates, a generalised increase in expected inflation provides a boost to inflation dynamics by reducing economy-wide real rates. Tracking the full set of inflation expectations across the range of economic actors (financial market participants, firms, households) is, of course, a demanding exercise. For instance, it is likely that firms and households do not revise beliefs as quickly as market participants, due to informational constraints and the logic of rational inattention in relation to cyclical fluctuations in the macroeconomic environment. Accordingly, at least for those economic actors that are slow to revise inflation beliefs, increases in nominal funding rates likely constitute an increase in perceived real funding rates. In relation to the inflation beliefs of financial market participants, we examine both market-based indicators of inflation compensation and the lower-frequency survey-based measures, such as the quarterly ECB Survey of Professional Forecasters (SPF). In turn, inferring a measure of expected inflation from the market measures of inflation compensation requires an assessment of the relative balance between variation in the “true” expected inflation component and variation in the inflation risk premium: such decomposition exercises are routinely conducted at the ECB.

Conclusions

Ensuring favourable financing conditions is central to restoring inflation momentum and guiding the formation of inflation expectations through the commitment of the central bank to counter the negative pandemic shock to the inflation path and secure convergence towards the inflation aim over the medium term.

In this environment, ample monetary stimulus remains essential to preserve favourable financing conditions over the pandemic period for all sectors of the economy. By helping to reduce uncertainty and bolster confidence, this will encourage consumer spending and business investment, underpinning economic activity and safeguarding medium-term price stability. In particular, the purchases made under the PEPP will be conducted to preserve favourable financing conditions over the pandemic period. We will purchase flexibly according to market conditions and with a view to preventing a tightening of financing conditions that is inconsistent with countering the downward impact of the pandemic on the projected path of inflation.

To recap the primary theme of this speech, the preservation of favourable financing conditions should involve the inspection of indicators along the whole transmission chain of our monetary policy – from risk-free rates to government borrowing costs to capital markets to the terms and pricing of bank lending to firms and households.

Within the broad-based set of indicators that is useful in monitoring whether financing conditions are favourable, the downstream conditions facing the households and firms that rely on bank-based credit play a prominent role, while the upstream indicators of risk-free OIS rates and sovereign yields are particularly important. In addition to their direct relevance for the firms and governments that raise funding in the bond market, these are also good early indicators of what happens at downstream stages of monetary policy transmission, since banks use those yields as a reference in pricing their loans to households and firms. Accordingly, the ECB is closely monitoring the evolution of longer-term nominal bond yields.

Finally, offsetting the pandemic shock to the inflation outlook is only the first stage of what monetary policy needs to accomplish. The December 2020 staff macroeconomic projections point to inflation still being well below our inflation aim at the end of the forecast horizon. The PEPP is providing crucial support to counter the downward shift in the inflation outlook caused by the pandemic and will continue until we judge that the coronavirus crisis phase is over. But we will need to continue providing ample monetary accommodation for an extended period, even after the disinflationary pressures caused by the pandemic have been sufficiently offset. The post-pandemic challenge will be to ensure that the monetary policy stance delivers the timely and robust convergence of inflation to our medium-term aim: in this context, our current monetary policy strategy review exercise is timely.

- I am grateful to Benjamin Böninghausen, Danielle Kedan and Petra Köhler-Ulbrich for their contributions to this speech.

- The importance of time-varying financial frictions in determining the transmission of monetary policy has been the focus of considerable research efforts in recent years. Recent examples include: Gertler, M. and P. Karadi (2015), “Monetary Policy Surprises, Credit Costs, and Economic Activity,” American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics, 7(1), pp. 44-76; Brunnermeier, M. and Y. Sannikov (2016), “The I Theory of Money,” mimeo, Princeton University; Dell’Ariccia, G., L. Laeven, L., and G. Suarez (2017), “Bank Leverage and Monetary Policy's Risk-Taking Channel: Evidence from the United States,” Journal of Finance, 72(2), pp. 613-654; Altavilla, C., F. Canova, and M. Ciccarelli (2020), “Mending the broken link: heterogeneous bank lending and monetary policy pass-through,” Journal of Monetary Economics, 110, pp. 81-98; Van der Ghote, A. (2019), “Interactions and Coordination between Monetary and Macro-Prudential Policies,” American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics, forthcoming; Caballero, R. and A. Simsek (2021), “A Model of Endogenous Risk Intolerance and LSAPs: Asset Prices and Aggregate Demand in a “Covid-19” Shock,” mimeo, MIT.

- This largely follows the explanation of the policy proposal in the public account of the monetary policy meeting of 9-10 December 2020. See also Lane, P.R. (2020), “Monetary policy in a pandemic: ensuring favourable financing conditions”, speech at Trinity College Dublin, November.

- The PEPP and TLTRO programmes build on the already-low level of the key policy rates. These core initiatives were accompanied by a suite of supporting measures, including the easing of the collateral framework along various dimensions. The monetary policy measures were flanked by a host of countercyclical measures quickly implemented by ECB Banking Supervision and national macroprudential authorities.

- This definition of external finance includes bank loans, debt securities, trade credit and other liabilities and excludes intercompany loans and equity. The figure of 43 per cent is the average over the period 2009-2018.

- The ECB also introduced temporary collateral easing measures in April 2020 to facilitate the availability of collateral against which banks can participate in Eurosystem refinancing operations. On the supervisory side, in March 2020 the ECB introduced temporary capital relief measures and encouraged banks to use their capital buffers to support bank lending to the economy.

- See also Lane, P.R. (2020), “The monetary policy response to the pandemic emergency”, ECB blog post, 1 May.

- For further discussion, see ECB (2014), “Euro area risk-free interest rates: measurement issues, recent developments and relevance to monetary policy”, Monthly Bulletin, July.

- See Lane, P.R. (2020), “The ECB’s monetary policy response to the pandemic: liquidity, stabilisation and supporting the recovery”, presentation at the Princeton BCF Covid-19 Webinar Series, 22 June.

European Central Bank

Directorate General Communications

- Sonnemannstrasse 20

- 60314 Frankfurt am Main, Germany

- +49 69 1344 7455

- media@ecb.europa.eu

Reproduction is permitted provided that the source is acknowledged.

Media contacts