Driving factors of and risks to domestic demand in the euro area

Published as part of the ECB Economic Bulletin, Issue 1/2019.

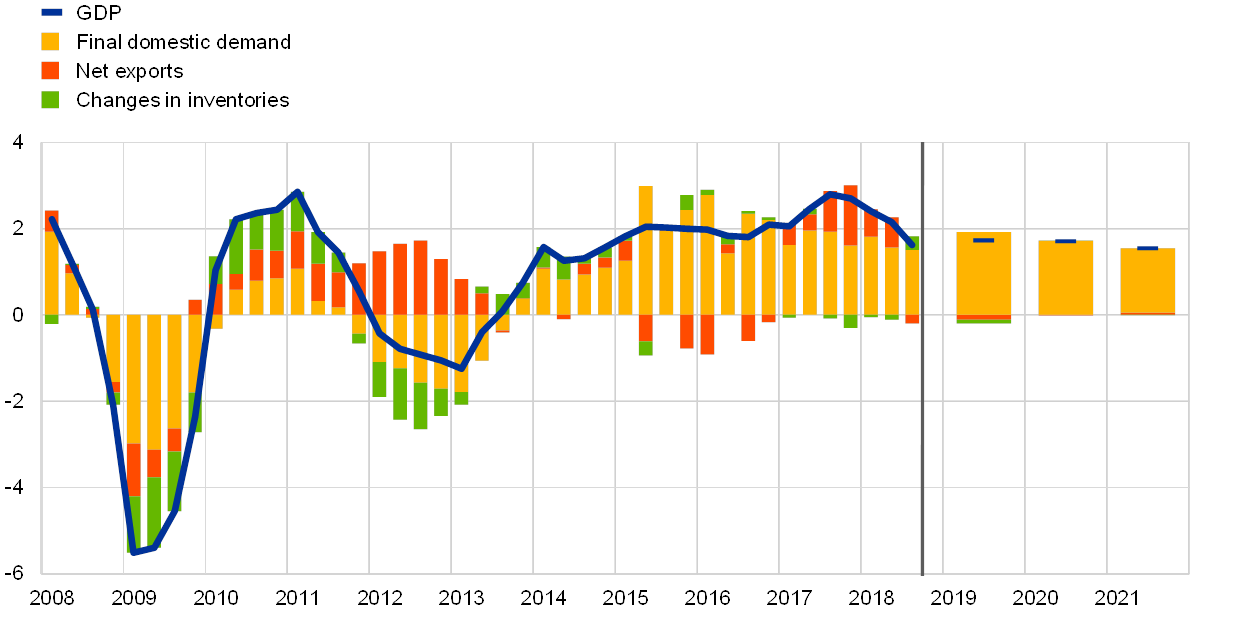

Activity in the euro area is expected to continue to expand at a moderate pace, while more elevated uncertainty points to intensified downside risks to the growth outlook. Heightened uncertainties at the global level, the prospect of Brexit, escalating protectionism, volatility in emerging market economies (EMEs) and policy uncertainty in some parts of the euro area pose major challenges to the sustainability of domestic demand going forward. According to the December 2018 Eurosystem staff macroeconomic projections,[1] the growth outlook is expected to be underpinned by sustained growth in domestic demand over the next few years, notwithstanding a very limited contribution from net exports and inventories (see Chart A). Even though growth is expected to slow, which is consistent with a maturing business cycle in which labour supply shortages increase in some countries and saving ratios recover from their low levels, activity is expected to be relatively resilient owing to a number of factors, including the expected continued expansion of global activity, the accommodative monetary policy stance supporting financing conditions, improving labour markets, rising wages and some fiscal loosening. This box reviews the factors underpinning domestic expenditure and assesses the potential adverse effects on domestic activity of heightened global uncertainty.

Chart A

Breakdown of euro area real GDP growth

(annual percentage changes and percentage point contributions)

Sources: Eurostat and December 2018 Eurosystem staff macroeconomic projections.

Notes: The latest observations of actual outcomes are for the third quarter of 2018. Data to the right of the vertical grey line are projections.

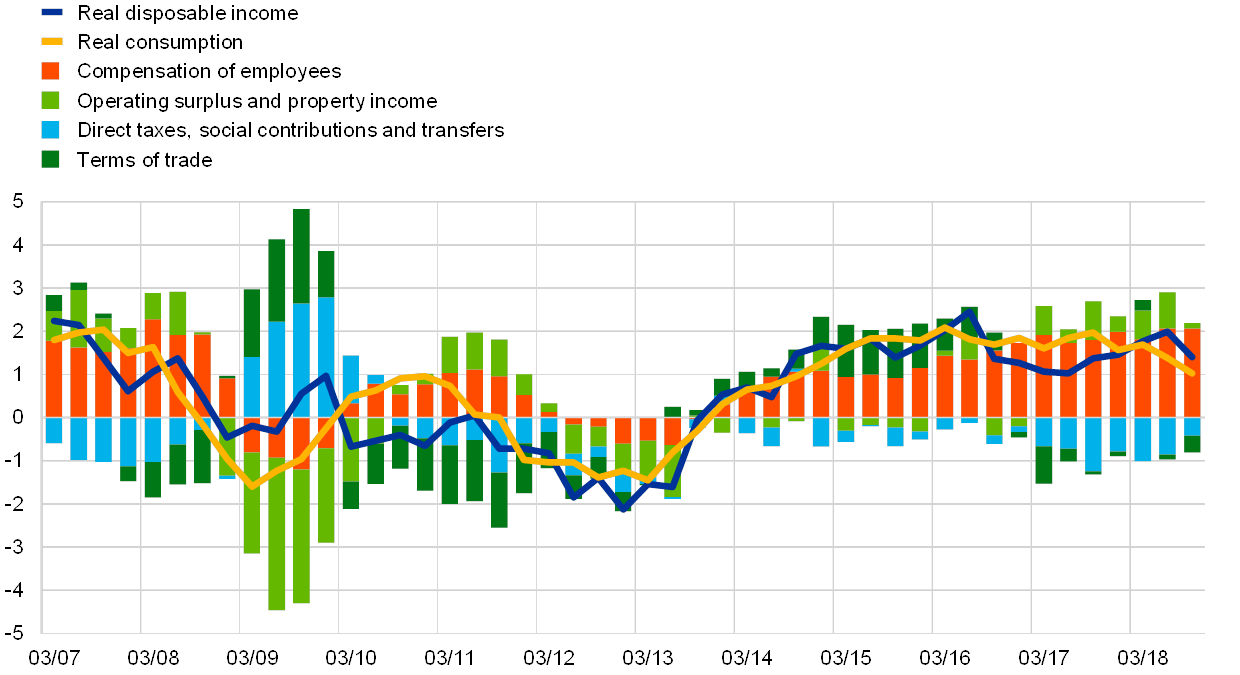

According to the December 2018 Eurosystem staff macroeconomic projections, private consumption is expected to remain supported by employment and income growth as important drivers of growth in household income. The moderation in euro area real GDP growth[2] in the first three quarters of 2018 was partly related to growth in private consumption, which slowed up to the third quarter. Consumer confidence declined in the course of 2018, but has remained above its long-term average. Looking forward, consumption growth is expected to continue to evolve in line with real disposable income developments. The main contribution to real disposable income growth stems from real labour income growth (see Chart B), which is expected to be driven to an increasing extent by wage developments and less by employment growth. This composition partly explains the slowdown in consumption growth, as the latter typically reacts more strongly to changes in employment than to income. The terms of trade – reflecting the relationship between export prices and import prices – are expected to improve and to provide additional support to disposable income[3] as oil prices are assumed to fall back after having risen in the third quarter of 2018, subject to the caveat that oil prices can be highly volatile, as recently witnessed. Property income is also expected to continue to support real disposable income. While fiscal policies overall have contributed negatively to disposable income in recent years, in line with the cyclical mechanism of fiscal stabilisers, they are expected to give some support to disposable income in 2019. In addition, progress achieved in household sector deleveraging should also support consumption, although household debt is still at a relatively high level. All in all, real disposable income will underpin private consumption while at the same time allowing a gradual build-up of household savings.

Chart B

Private consumption and breakdown of disposable income growth

(annual percentage changes and percentage point contributions)

Sources: Eurostat and ECB calculations.

Notes: The contribution from terms of trade is proxied by the differential between the GDP and consumption deflators. The latest observations are for the third quarter of 2018.

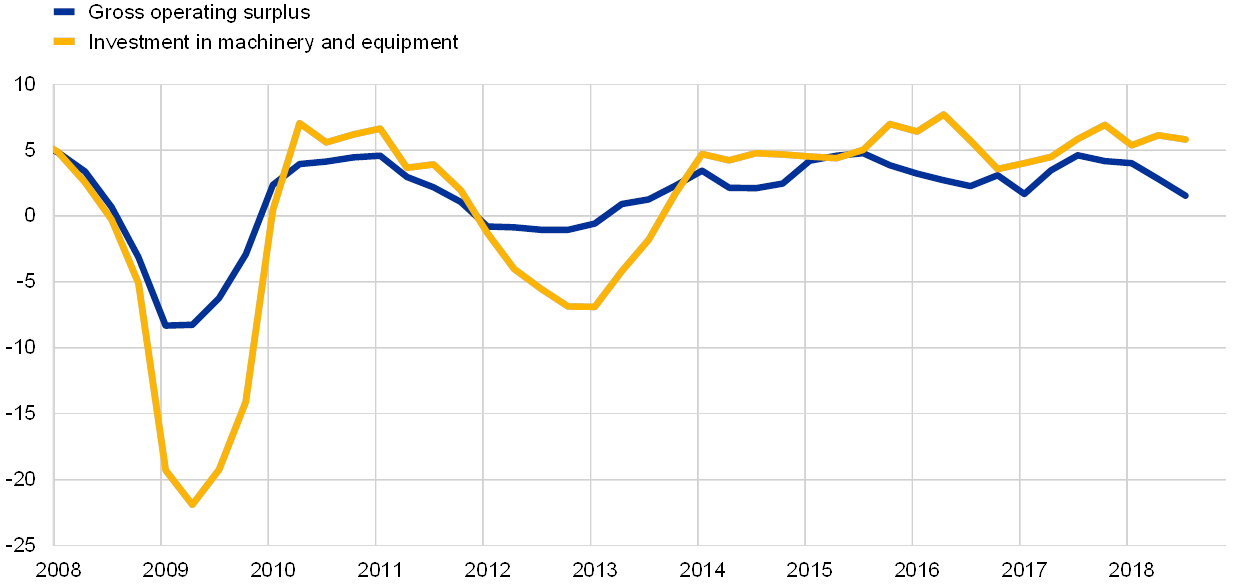

In the context of a maturing business cycle, growth in business investment is still expected to continue, despite a more uncertain environment. Business investment will be underpinned by domestic demand developments, capacity constraints and profitability in line with historical patterns (see Chart C), albeit exhibiting a slowing pace as the business cycle matures and profit and demand conditions weaken. Financial conditions remain accommodative, but are expected to gradually become less supportive of investment. In addition, improving balance sheets and easing liquidity needs for euro area firms will also support business investment. As for the housing market, short-term indicators at the turn of the year – such as subdued Purchasing Managers’ Index levels and construction production – reflect rising labour shortages in some countries and point to a near-term deceleration in housing investment growth. Nevertheless, the medium-term upturn in housing investment should continue from below pre-crisis levels in many of the larger euro area countries, supported by house price developments.

Chart C

Growth in machinery and equipment investment and profits

(annual percentage changes)

Source: Eurostat.

Note: The latest observations are for the third quarter of 2018.

There are also signs that growth is increasingly supported by structural factors as well as cyclical ones, despite some vulnerabilities. The reduction in macroeconomic imbalances, notably in former programme countries, and structural reforms have strengthened the euro area’s resilience and the effectiveness of monetary policy. This should also reduce adverse repercussions of idiosyncratic shocks in euro area countries. At the same time, potential vulnerabilities stem from, among other things, still high public and private debt levels, non-performing loans on banks’ balance sheets, below pre-crisis household savings and remaining structural rigidities in some countries.

The resilience of the domestic demand components could be particularly challenged by increasing global uncertainty related inter alia to an escalation in trade tensions. As for private consumption, data suggest that labour income growth can be expected to continue to support household spending, despite possible adverse impacts from global trade uncertainty. This is evidenced by survey data on employment expectations, which remain at high levels overall, although prospects in sectors more exposed to trade (e.g. manufacturing) have declined somewhat (see Chart D).

Chart D

Employment expectations

(diffusion index: 50 = no change on previous month)

Source: European Commission.

Note: The latest observations are for December 2018.

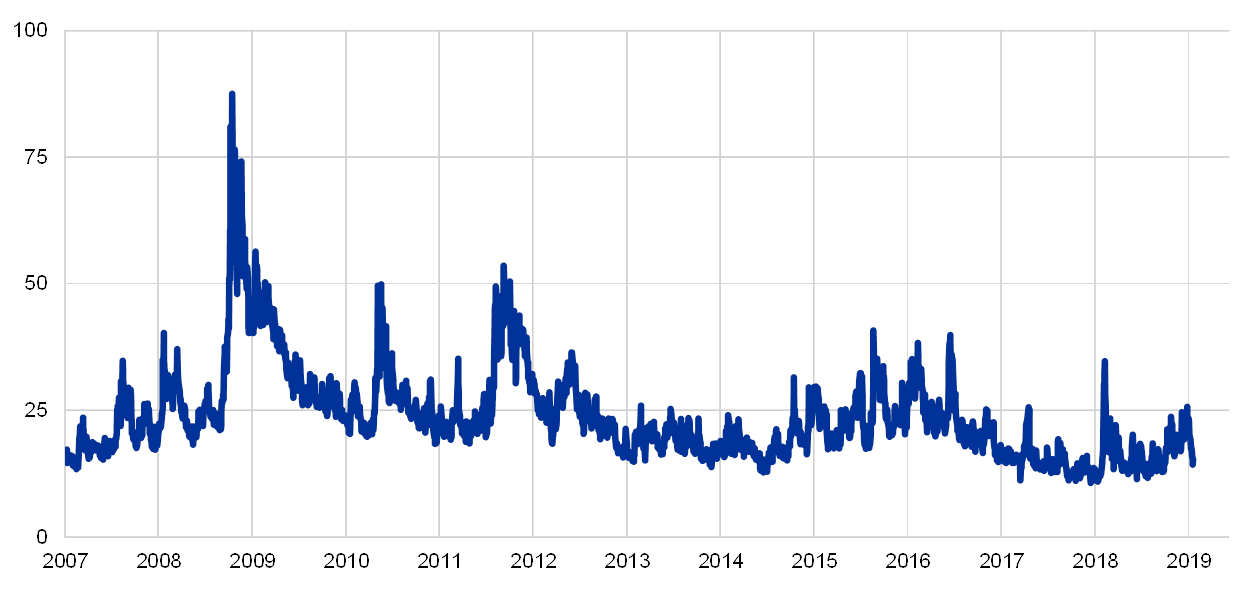

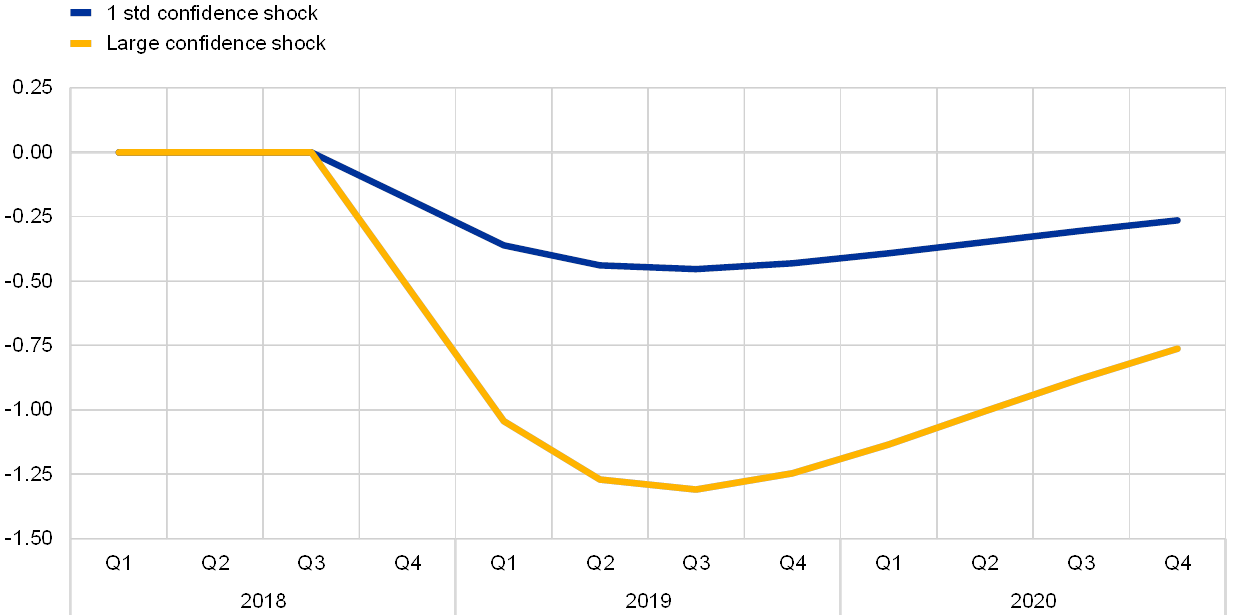

The adverse impact of heightened global uncertainty could potentially be greater for business investment than for private consumption, according to survey data and model evidence. While uncertainty is difficult to measure, heightened uncertainty has a well-documented adverse impact on business investment decisions.[4] As evidence of this impact, country surveys suggest that increasing global uncertainty is causing some delay in investment decisions.[5] In order to assess the impact, two simulations were run using the ECB’s multi-country forecast model.[6] In both simulations, the residuals of the investment equations for the largest euro area countries in the model were shocked to replicate an increase in the VIX volatility index (see Chart E), exploiting historical correlations between the VIX and the residuals. In the first scenario, the VIX was increased by one standard deviation of the index in the fourth quarter of 2018, with subsequent values of the VIX in line with its historical persistence pattern. This shock leads to lower investment, with an adverse impact that peaks in the second half of 2019 (see Chart F). In a second scenario, the initial increase in the VIX matches the quarter-on-quarter increase in the VIX observed at the height of the European sovereign debt crisis, with the subsequent values of the VIX also following historical patterns. The simulation yields a larger adverse impact on investment (see Chart F). In both scenarios, almost half of the peak loss in the investment level is recovered after 2.5 years as uncertainty subsides.

Chart E

VIX volatility index

(percentages)

Source: Haver Analytics.

Note: The latest observation is for 21 January 2019.

Chart F

Impact of uncertainty shocks on euro area total investment

(percentages; deviation from baseline)

Source: ECB calculations.

Notes: The scenarios considered are based on historical VIX patterns, as captured through an AR(1)MA(1) regression on 12 years of quarterly averaged VIX data. The one standard deviation (1 std) confidence shock amounts to an initial increase of 5.5 percentage points, which is in line with the increase in the quarterly averaged VIX levels between the third and fourth quarters of 2018. The larger confidence shock scenario, based on the increase in volatility at the height of the European sovereign debt crisis, amounts to an initial increase of 16 percentage points.

To conclude, domestic demand growth, in particular private consumption, will remain a key driver of activity over the next few years, albeit with a diminishing contribution, reflecting the expected maturing of the business cycle. Meanwhile, increasing uncertainties at the global level constitute a downside risk to the outlook, particularly for business investment.

- See the “December 2018 Eurosystem staff macroeconomic projections for the euro area”, ECB, 2018.

- See the box entitled “The recent slowdown in euro area output growth reflects both cyclical and temporary factors”, Economic Bulletin, Issue 4, ECB, 2018.

- See the box entitled “Oil prices, the terms of trade and private consumption”, Economic Bulletin, Issue 6, ECB, 2018.

- In response to uncertainty shocks, firms can adjust their inventory policies by disproportionately cutting their orders of foreign intermediates, leading to a bigger contraction in international trade flows than in domestic economic activity (see, for example, Novy, D. and Taylor, A.M., “Trade and Uncertainty”, CEP Discussion Paper, No 1266, Centre for Economic Performance, May 2014). An uncertain trade policy outlook gives firms a reason to delay entry into a foreign market (extensive margin) and to delay upgrading their technology (intensive margin) (see Handley, K. and Limão, N., “Trade and Investment under Policy Uncertainty: Theory and Firm Evidence”, American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, Vol. 7, No 4, November 2015). The impact of trade policy uncertainty can be magnified by global value chains (GVCs) (see Osnago, A., Piermartini, R. and Rocha, N., “The Heterogeneous Effects of Trade Policy Uncertainty: How Much Do Trade Commitments Boost Trade?”, Policy Research Working Paper, No 8567, World Bank, August 2018).

- See, for example, Economic Bulletin, No 4, Banca d’Italia, 2018; “The air is getting thinner”, DIHK Economic Survey, Fall 2018, Association of German Chambers of Industry and Commerce, October 2018; and Economic Bulletin, No 3, Banco de España, 2018.

- See Dieppe, A., Gonzáles-Pandiella, A. and Willman, A., “The ECB’s New Multi-Country Model for the euro area: NMCM – Simulated with rational expectations”, Economic Modelling, Vol. 29, Issue 6, 2012, pp. 2597-2614; and Dieppe, A., Gonzáles-Pandiella, A., Hall, S. and Willman, A., “Limited information minimal state variable learning in a medium-scale multi-country model”, Economic Modelling, Vol. 33, 2013, pp. 808-825.