- SPEECH

Unequal scars – distributional consequences of the pandemic

Speech by Isabel Schnabel, Member of the Executive Board of the ECB, at the panel discussion “Verteilung der Lasten der Pandemie” (“Sharing the burden of the pandemic”), Deutscher Juristentag 2020

Frankfurt am Main, 18 September 2020

The coronavirus (COVD-19) pandemic is the most severe crisis in post-war history.[1] It threatens the health of the population, poses enormous challenges to the healthcare system and is causing significant economic costs. Within a short period of time, wide-ranging government support measures were introduced in an attempt to cushion some of the direct consequences of the crisis. In light of the enormous economic costs of the pandemic and the measures taken thus far, questions have been raised about how the economic burden of the crisis will be financed and distributed.

The pandemic is a global shock that has hit all euro area countries almost simultaneously. Since then, however, it has become increasingly clear that the pandemic is having very different impacts on different countries. Those countries that already exhibited low growth and limited fiscal space before the crisis have been affected most severely. As a consequence, the pandemic threatens to exacerbate existing cross-country differences.

However, differences are not only emerging between countries. Within countries, too, there are strong indications that pre-existing inequalities are being reinforced by the crisis. Lower-income individuals, those with lower levels of education as well as women and young people are affected the most.

The common monetary policy of the European Central Bank (ECB) has limited means to counteract this type of divergence. Instead, it is the task of fiscal policy to implement targeted measures to prevent the resulting inequality from turning into a structural phenomenon.

Threat of divergence at country level

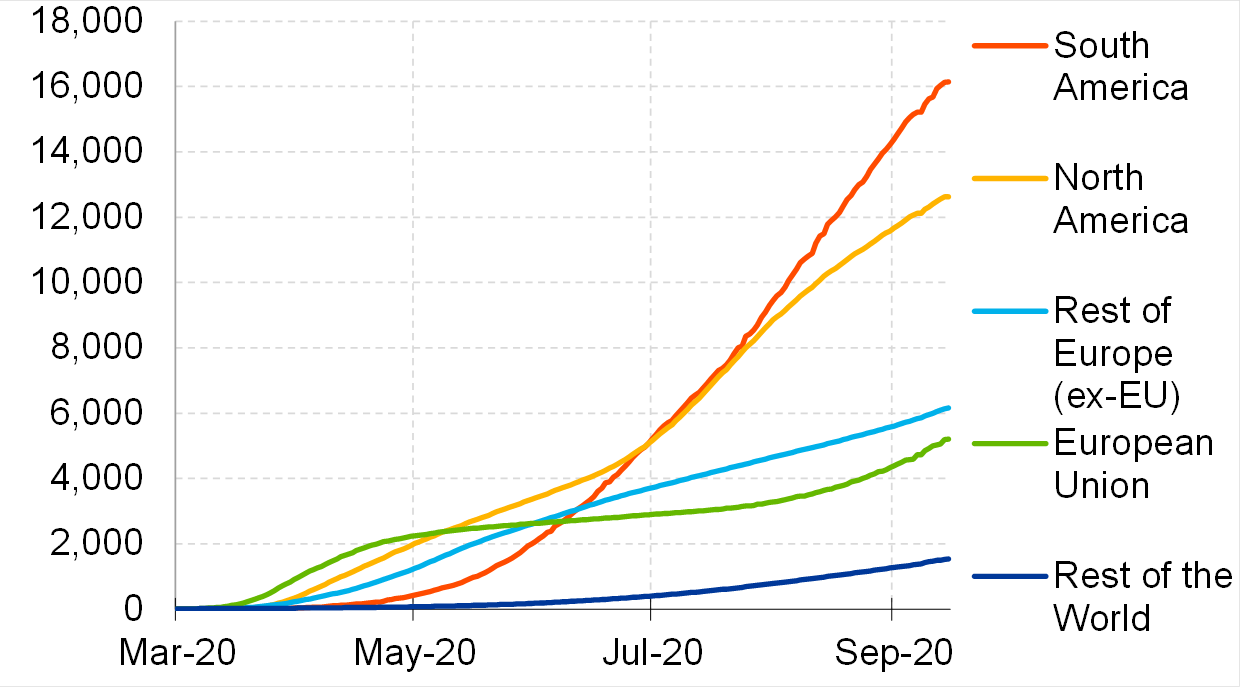

Significant cross-country differences can already be identified when considering the development of COVID-19 cases over time. The figures in Europe have been relatively benign by international standards, while North and South America, for instance, have reported considerably more dramatic increases in total infection numbers (Figure 1).

Figure 1

Total number of COVID-19 infections worldwide.

Per million inhabitants

Source: Bloomberg.

Note: Counts are subject to change as governments survey and confirm cases. Data are based on reported infection numbers as of midnight EST at each date. Sources also include Johns Hopkins University, World Health Organization, DXY, NHC, BNO News, China CDC, European CDC, US CDC, Italy Ministry of Health, Hong Kong Department of Health, Macau Government, Taiwan CDC, Government of Canada, Australia Government Department of Health, and Ministry of Health Singapore.

Nevertheless, the situation within Europe is far from homogenous. In recent weeks, a particularly strong increase in active COVID-19 infections has been observed in Spain and France, while Germany and Italy have been recording low numbers, relative to the size of each country’s population (Figure 2).

Figure 2

Number of active COVID-19 infections in Europe.

Per million inhabitants

Source: Bloomberg.

Note: Active case numbers based on a 7-day moving average. Counts are subject to change as governments survey and confirm cases. Data are based on reported values as of midnight EST at each date. Based on population data as of 3 September 2020. Sources include Johns Hopkins University, World Health Organization, DXY, NHC, BNO News, European CDC, Italy Ministry of Health.

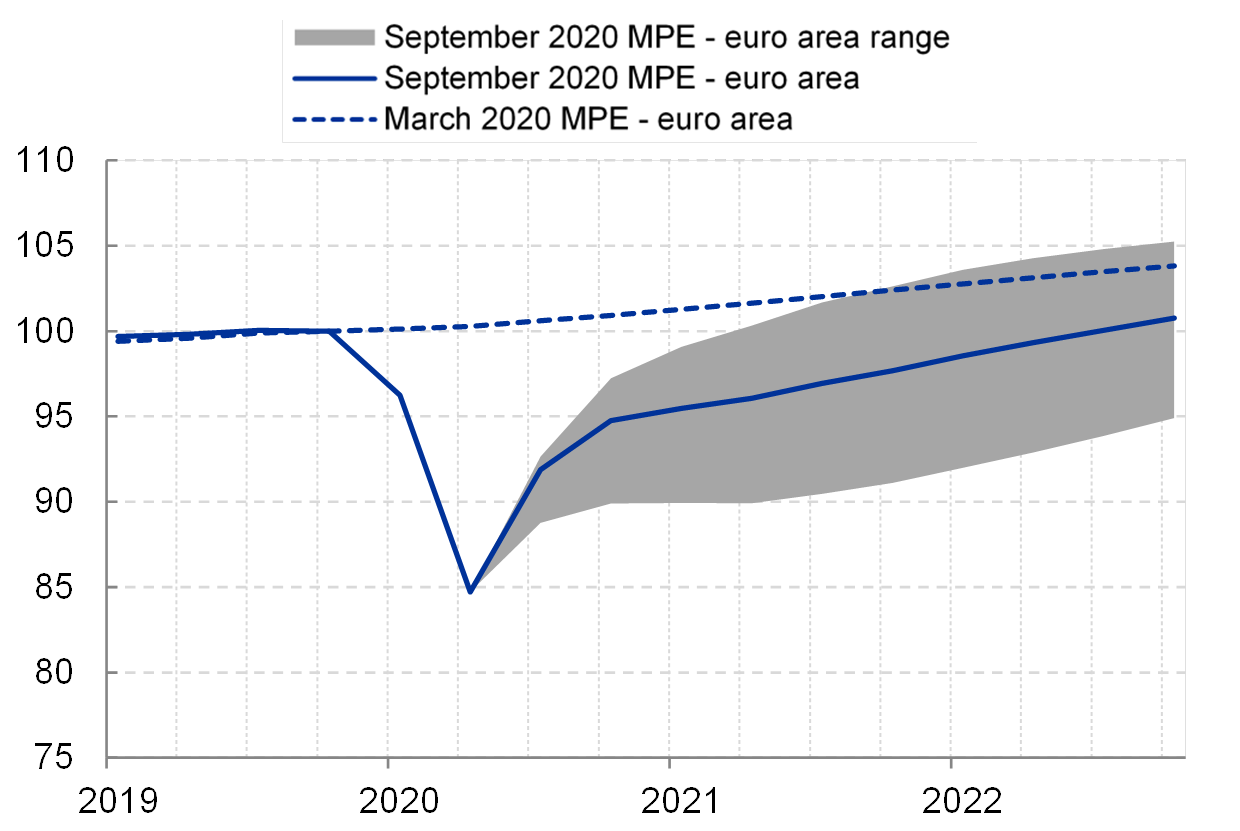

The economic fallout from the pandemic is severe. The lockdown measures imposed by governments led to a sharp decline in gross domestic product (GDP), causing the euro area economy to contract by 11.8% in the second quarter (Figure 3). While a strong recovery is expected in the third quarter, the most recent ECB staff projections estimate euro area GDP at end-2022 to be around 3% below the growth path that had been forecast as recently as March.[2] It may therefore take years to completely overcome the economic damage caused by the crisis.

Figure 3

Real Gross Domestic Product (GDP): euro area.

Index: 2019Q4 = 100

Source: ECB (Macroeconomic Projection Exercise, September 2020).

Note: The grey area indicates the range of ECB staff projections that cover the different pandemic scenarios included in the Macroeconomic Projection Exercise.

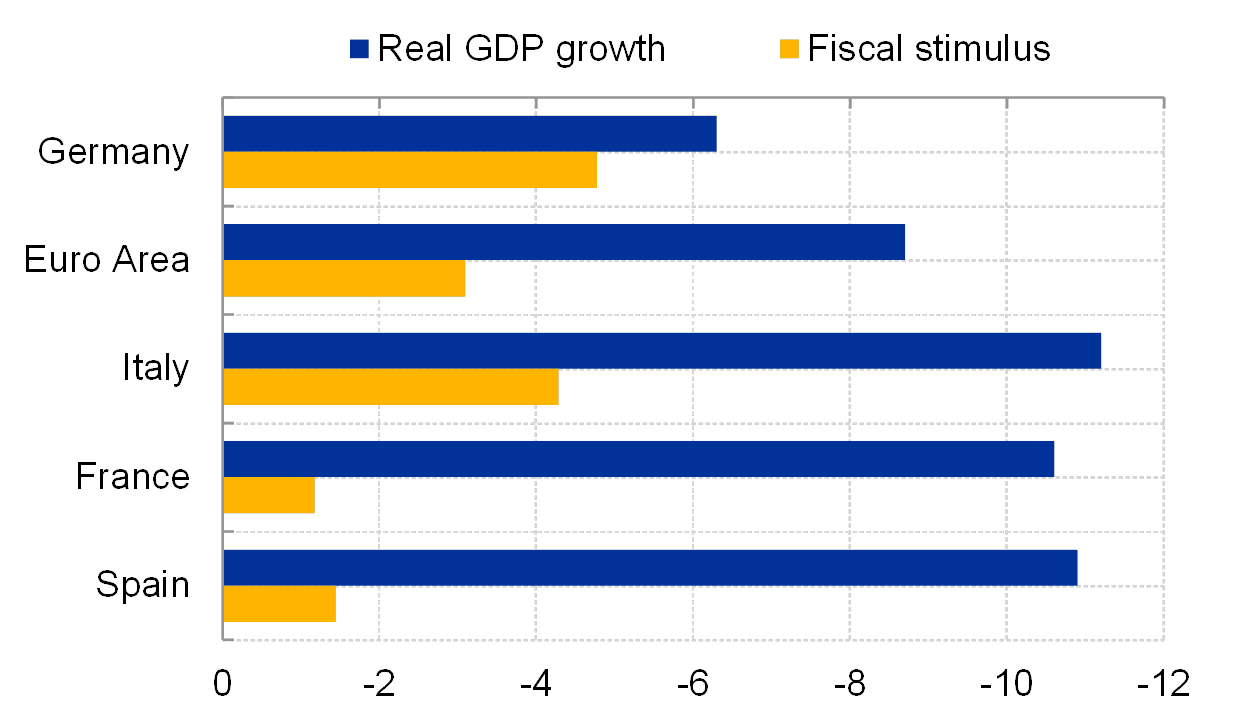

In this context, too, significant differences are observable across euro area countries. While the European Commission’s forecast estimates that Germany’s GDP will fall by 6.3% in 2020, the contraction in GDP for France, Italy and Spain is expected to exceed 10% (Figure 4). It is unlikely that the resumption of economic growth in 2021 will significantly reduce these differences. Risks of an increasing cross-country divergence in economic performance therefore continue to persist.

Figure 4

Annual growth rate of real GDP: Germany, France, Italy, Spain.

Percent

Source: European Commission (Summer Economic Forecast, July 2020).

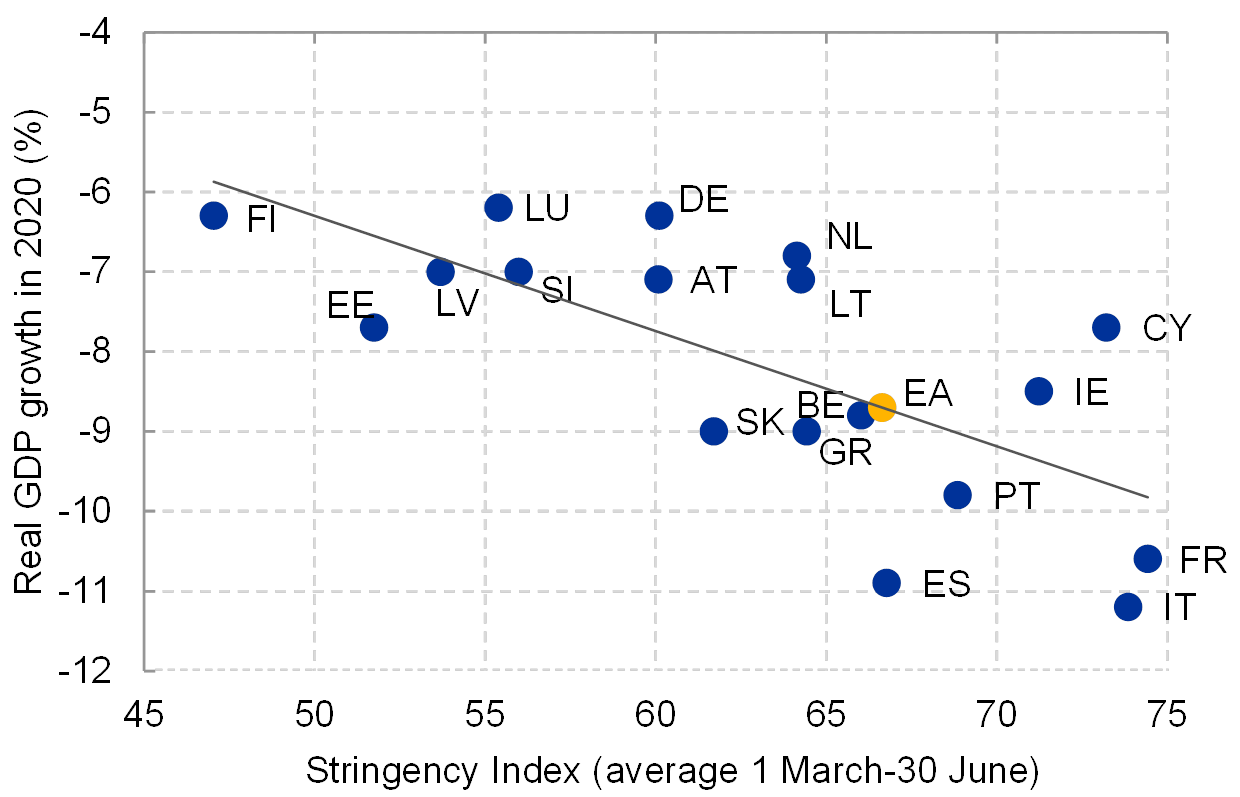

In this context, the economic consequences of the pandemic depend significantly on the severity of lockdown measures that were imposed in the first few months of the pandemic in order to contain the spread of the virus. There is a clear negative correlation between the extent of government-imposed restrictions, measured by the Oxford Stringency Index, and the fall in GDP projected for 2020 (Figure 5). However, the severity of the lockdown measures cannot fully explain the divergence in economic performance, as exemplified by the comparison between the Netherlands and Greece.

Figure 5

Stringency of national crisis measures vs. projection of real GDP growth rate in 2020.

Index, percent

Source: European Commission (Summer Economic Forecast, July 2020), University of Oxford.

Note: The Oxford Stringency Index defines the stringency of national crisis measures between 0 (no restrictions) and 100 (maximum level of restrictions).

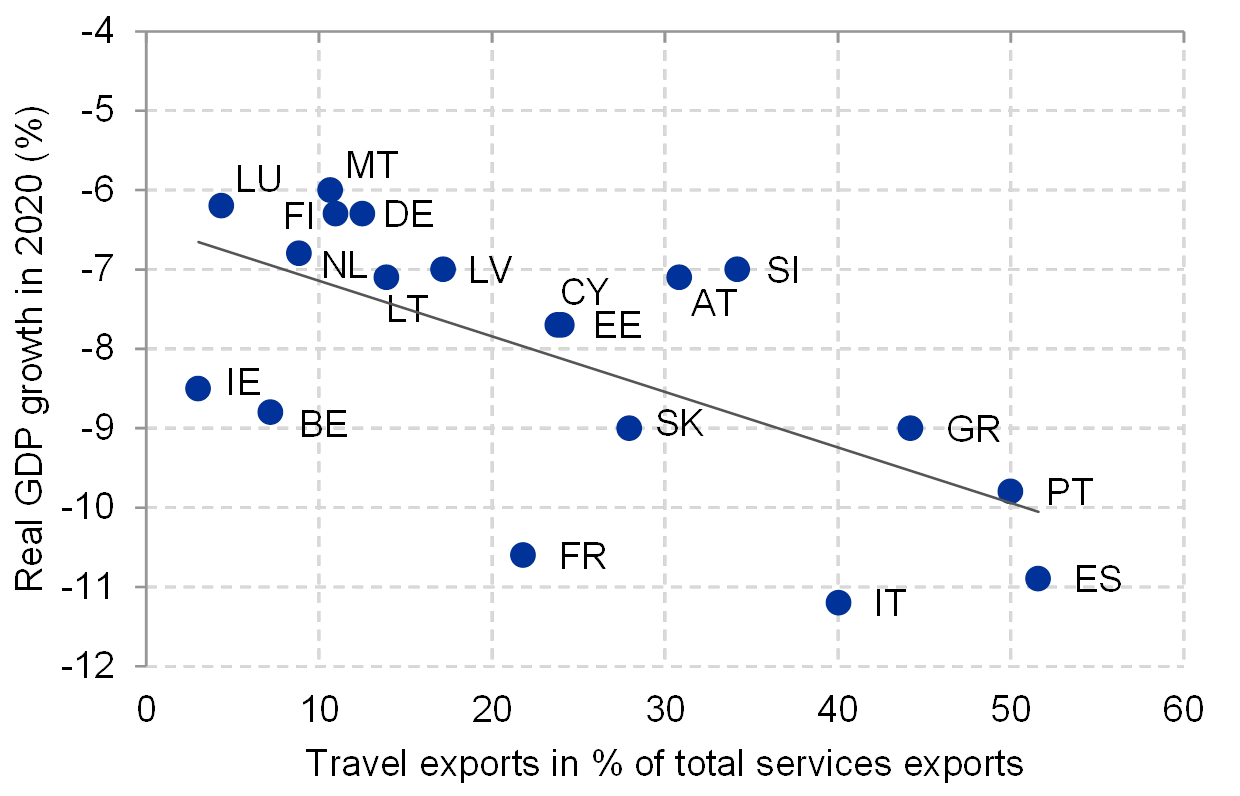

Europe-wide travel restrictions and the drop in demand for travel abroad led to considerable economic losses in countries with a relatively high dependency on tourism, such as Greece or Spain. A correlation analysis shows that the projected drop in economic activity tends to be most pronounced in those countries (Figure 6).

Figure 6

Travel exports as a share of total services exports vs. projection of real GDP growth rate in 2020.

Percent

Source: European Commission (Summer Economic Forecast, July 2020), Eurostat Balance of Payments.

Owing to differences in sectoral composition, the share of the workforce employed in sectors that are particularly affected by the restrictions varies significantly across countries (Figure 7). These structural factors have further reinforced differences in the impact of the pandemic on different countries. In Spain and Italy, for example, the share of the workforce employed in sectors that are most affected by lockdown measures is particularly high, exceeding 30%.

Figure 7

Share of employees in lockdown sectors.

Percent

Source: EU Statistics on Income and Living Conditions (EU-SILC), 2018.

Note: The chart shows the distribution of the share of employees in lockdown sectors across 6 largest euro area countries. Lockdown sectors are: wholesale and retail trade, repair of motor vehicles and motorcycles; transporting and storage; accommodation and food service activities; arts, entertainment and recreation (sectors G, H, I and R in the Statistical Classification of Economic Activities in the European Community (NACE) classification).

Economic policy reaction: fiscal and monetary policy as complements

Despite the magnitude of the economic downturn, unemployment has only increased marginally so far (Figure 8). This partly results from a drop in labour market participation, given that some individuals currently do not actively seek employment due to social distancing rules or childcare duties.[3] Moreover, euro area countries have implemented large-scale job retention programmes, thus preventing lay-offs and unemployment. The German Kurzarbeitergeld (short-time work allowance) is an example of such a scheme. In the context of these government support programmes, significant heterogeneity across member countries is also apparent. Nevertheless, due to these measures, a considerable increase in unemployment was most likely averted in all countries.

Figure 8

Unemployment rate and share of workers in job retention schemes.

Percent

Source: Eurostat; Bundesagentur für Arbeit and ifo Institute Munich; Ministère du Travail, de L’Emploi et de L’Insertion; INPS; Ministerio de Inclusión, Seguridad Social y Migraciones, and ECB staff computations.

Latest observation: July 2020 for the unemployment rate; July 2020 for the number of workers in ERTE in Spain; June 2020 for the number of workers in Kurzarbeit in Germany and Activité Partielle in France; May 2020 for the number of workers in Cassa Integrazione in Italy.

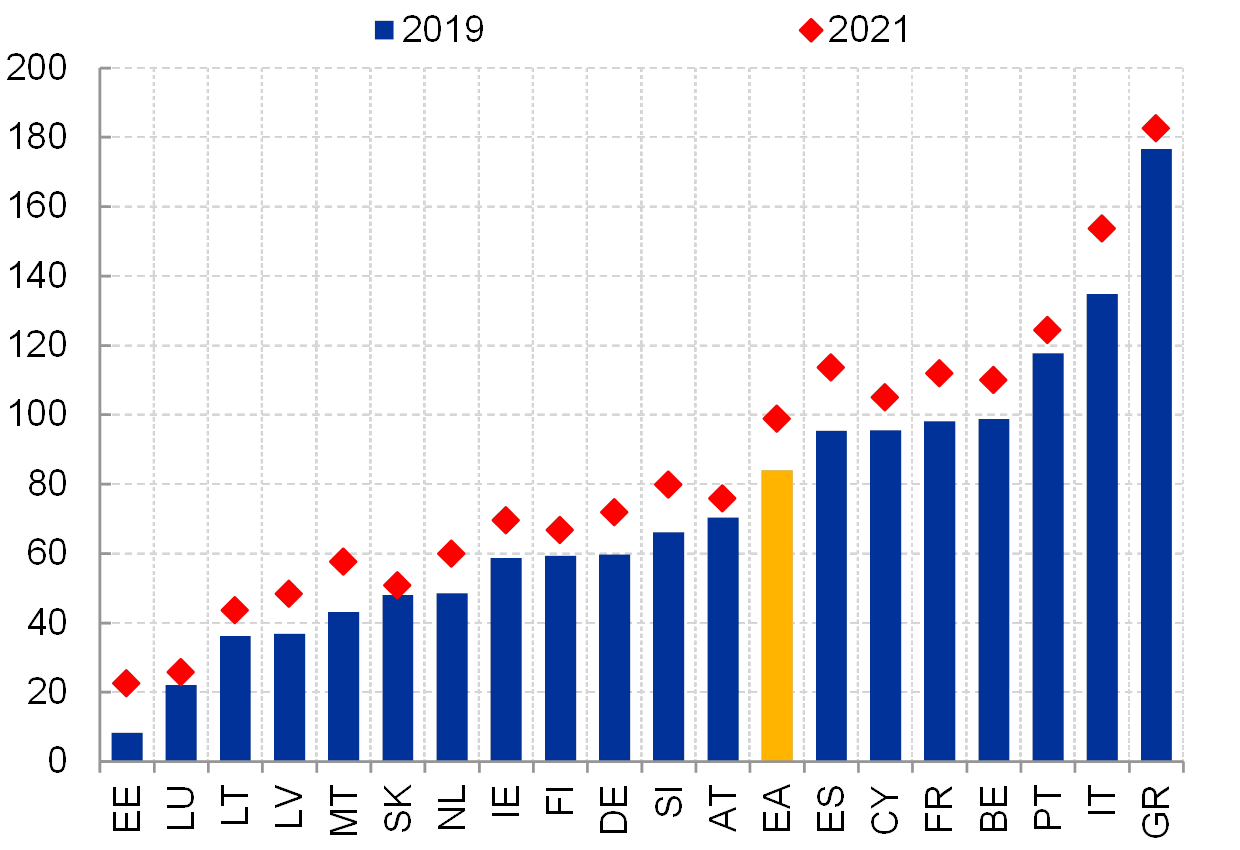

In addition to job retention schemes, euro area countries have launched a large number of further fiscal measures to support households and companies in the wake of the pandemic. The resulting funding needs will lead to a considerable medium-term increase in public debt levels in all euro area countries (Figure 9).

Figure 9

Public debt in the euro area in 2019 vs. projection for 2021

Percent of GDP

Source: European Commission (Spring Economic Forecast, May 2020).

The impact of the pandemic has been particularly harsh in those countries that had already incurred a high level of public debt before the current crisis. A high level of public debt limits the scope for fiscal stimulus measures. In this context, a widely shared concern at the start of the crisis was that the fiscal response in these countries would be insufficient. Indeed, a negative correlation between the extent of the fiscal stimulus measures and the severity of the expected economic contraction was initially observed (Figure 10). It should also be highlighted that the stronger impact of the coronavirus crisis in these countries had not, or only to a limited extent, been caused by misguided government policies.

Figure 10

Projection of real GDP growth rate in 2020 and fiscal stimulus.

Percent

Source: European Commission (Ameco).

Note: Real GDP growth estimates are based on data published by the European Commission (Summer Economic Forecast, July 2020). Fiscal stimulus estimates are based on data published by the European Commission (Spring Economic Forecast, May 2020), the most recent harmonised projection. These estimates therefore do not include the latest announcements of fiscal support measures. Fiscal stimulus is calculated as the change in the primary deficit, adjusted for cyclical effects.

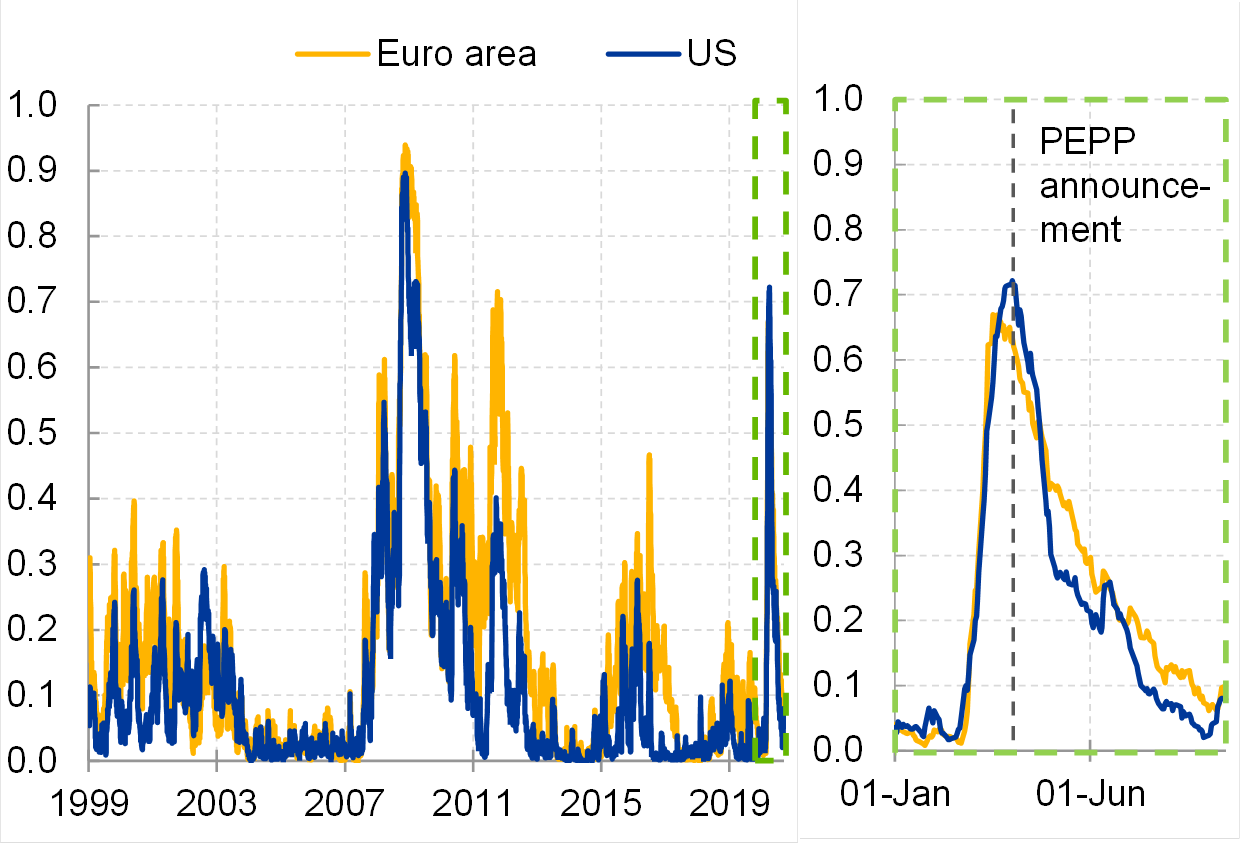

Since the crisis hit Europe, concerns about increasing fragmentation in the euro area have also dominated financial market developments. In March, monetary policy was faced with a rapidly deteriorating market environment. Investors fled to the safest securities and asset classes. Risk premia in other market segments rose dramatically, liquidity dried up, and financing conditions worsened considerably. Companies were confronted with acute liquidity shortages as revenues plummeted abruptly. The composite indicator of systemic stress (CISS) used by the ECB suggests that the European financial sector was most likely facing an imminent and severe financial crisis, which was only averted by a decisive and swift policy response on the part of the ECB (Figure 11).

Most notably, the measures comprised the provision of abundant liquidity to banks at extremely favourable conditions, as well as a temporary asset purchase programme tailored specifically to the pandemic crisis – the pandemic emergency purchase programme (PEPP). The design of the PEPP allows asset purchases to be distributed flexibly over time, across asset classes and among jurisdictions. The announcement of PEPP had an immediate and calming effect on financial markets.

Figure 11

Indicator for systemic stress in financial markets.

Index

Source: ECB Working Paper No. 1426.

Note: CISS denotes the Composite Indicator of Systemic Stress (0 = No stress,1 = High stress). The indicator aggregates stress signals from money, bond, equity and foreign

exchange markets.

Latest observation: 14 September 2020.

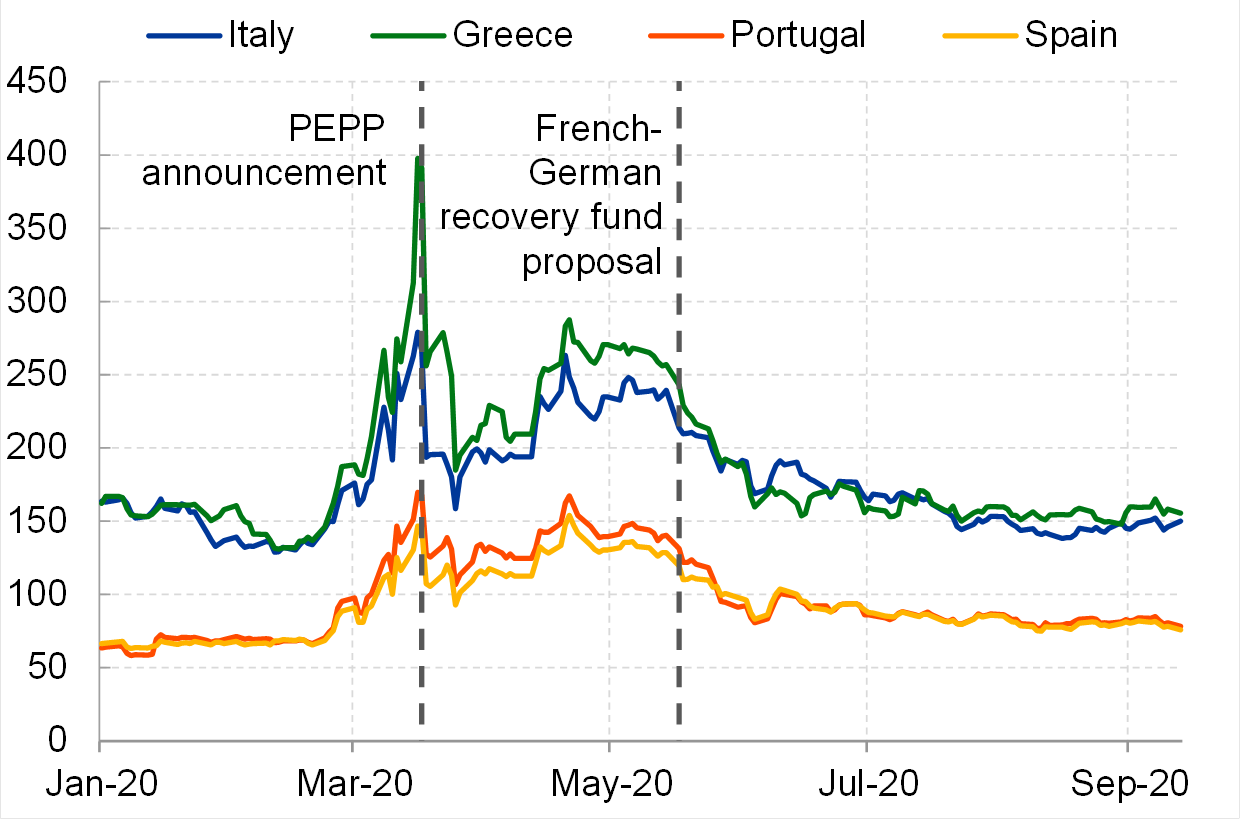

In particular, the PEPP effectively countered risks of fragmentation in European financial markets, which would have prevented the smooth transmission of our monetary policy measures to the entire euro area. Risk premia in European government bond markets declined markedly and have reverted approximately to their pre-crisis levels (Figure 12). This had a direct impact on the funding costs for households and enterprises in the euro area, thereby cushioning the economic impact of the crisis.

Figure 12

10-year yield spreads of selected government bonds over German equivalents.

Basis points

Source: Bloomberg.

Latest observation: 16 September 2020.

However, risk premia on government bonds did not decrease solely because of the monetary policy response. In addition, the agreement on a large-scale rescue package at European level contributed to a normalisation of risk premia. The fiscal support measures comprising loans and transfers were essential in reducing risk premia to their pre-crisis levels.

The agreement on the rescue package was not merely a sign of European solidarity during the crisis. It was also recognition of the fact that a substantial divergence in economic performance would ultimately be detrimental to all European countries. As a consequence, the funds should primarily benefit those countries that were most affected by the crisis and only have limited fiscal space available.

Unlike in the global financial crisis and the European sovereign debt crisis, a decisive European response was implemented quickly. Unlike back then, monetary and fiscal policy are today acting in a complementary manner and are reinforcing each other. This policy response made it possible to effectively counter what is undoubtedly the most severe economic crisis in living memory.

Rising inequality as a result of the pandemic

The crisis has not only left scars of varying depth at the country level. The consequences of government-imposed lockdown measures can also be differentiated according to the socioeconomic characteristics of the affected individuals. Based on empirical data, a number of recent academic studies consider the social consequences of the pandemic at an individual level.

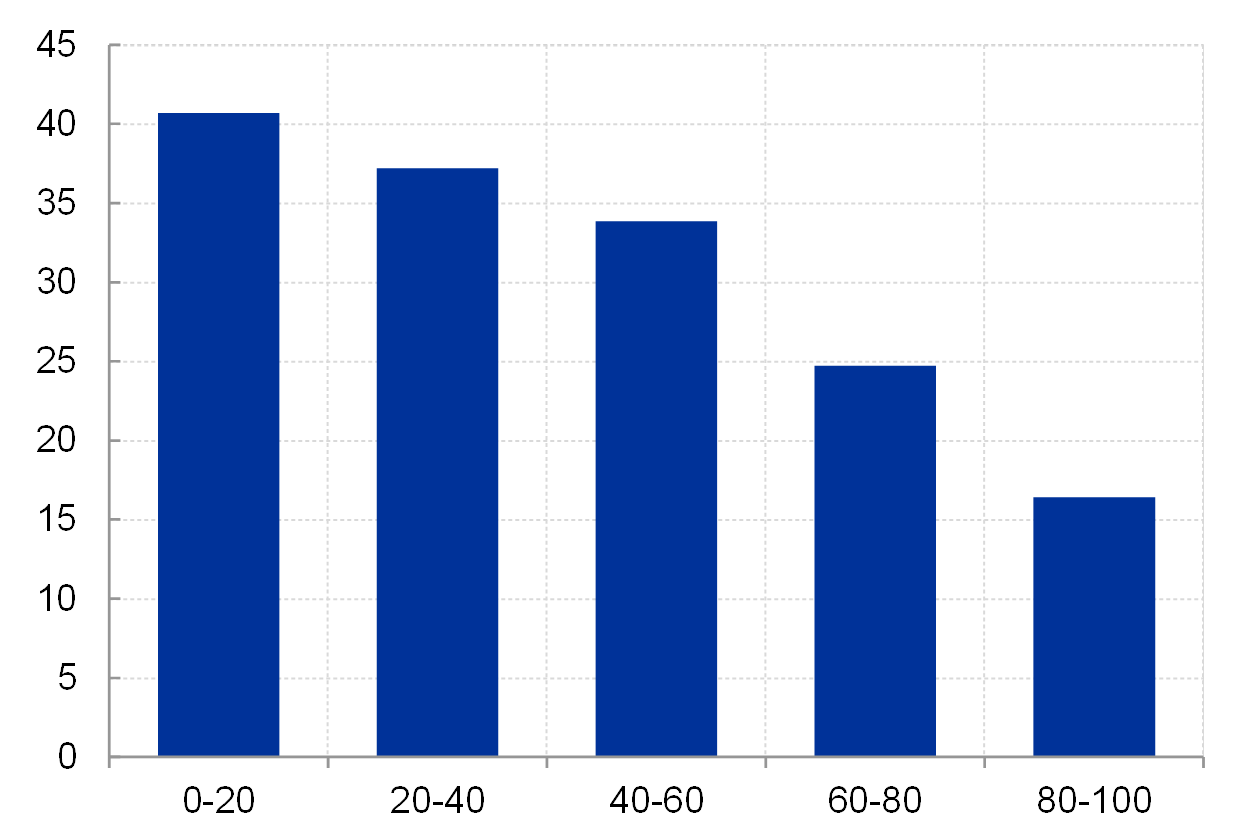

The findings of these studies suggest that the lockdown measures had a particularly marked impact on sectors in which work under physical distancing rules was difficult or almost impossible. Data for the euro area show that the share of employees in the most affected sectors increases notably in income (Figure 13).

Figure 13

Share of employees in lockdown sectors by income quintiles.

Percent

Source: EU Statistics on Income and Living Conditions (EU-SILC), 2018; Ireland and Slovakia 2017.

Note: The chart shows the distribution of the share of employees in lockdown sectors across quintiles of the income distribution in the euro area.

In a recent study, Mongey et al. (2020) use US data to show that employees in lockdown sectors typically have lower levels of education, lower incomes and lower savings than employees outside of the sectors directly affected by these measures.[4] Beland et al. (2020) obtain similar results.[5] Social distancing rules could thus contribute to an increase in income inequality.

Chetty et al. (2020) find that particularly large job losses in the United States occurred in companies that operate in lockdown industries and offer personal services catering to high-income households.[6] To a large extent, these job losses affected low-income employees. This finding also suggests that government-imposed lockdown measures could increase inequality further.

Indeed, Furceri et al. (2020) show that previous pandemics had the effect of amplifying income inequality.[7]

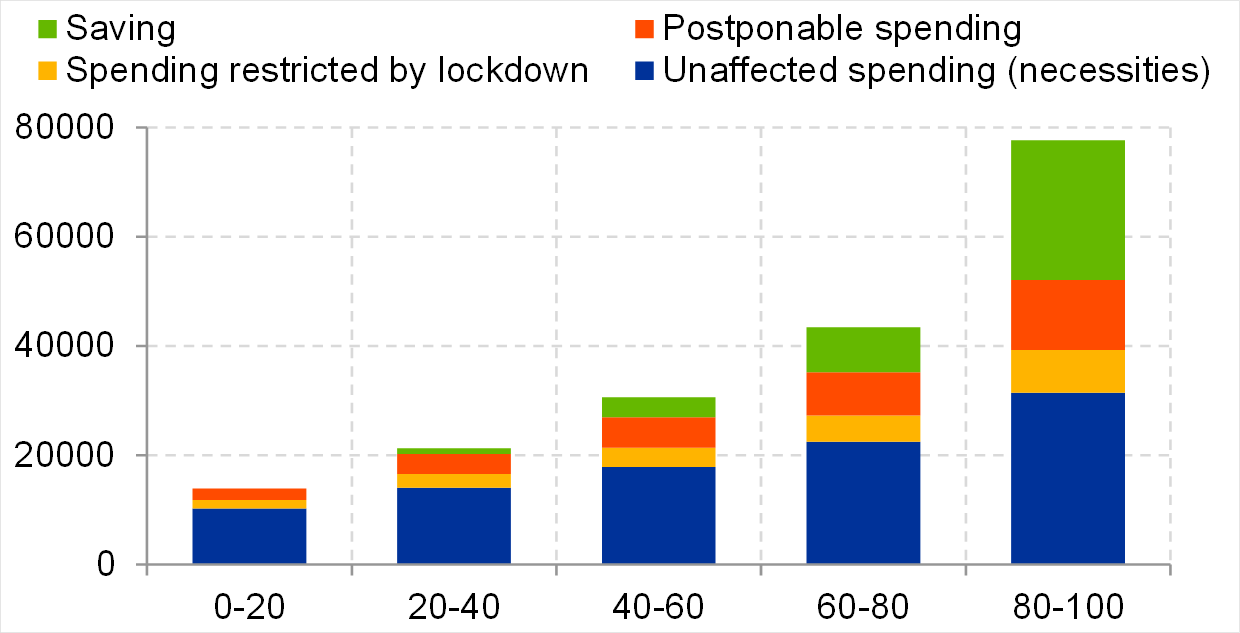

These consequences of the crisis are relevant from a macroeconomic – and monetary policy – perspective because patterns of consumption and savings differ greatly across various income groups. Whereas individuals located at lower levels of the income distribution spend most of their income on basic necessities, the shares of savings and consumer spending that could be postponed during the crisis is particularly high at the top of the income distribution (Figure 14). An increase in inequality therefore has an impact on the effectiveness of fiscal and monetary policy measures.[8]

Figure 14

Categories of spending and savings by income quintiles.

Percent

Source: Household Budget Survey.

Note: The chart shows the structure of household expenditures (spending) and saving across income quintiles. Blue bars denote necessities, items unaffected by lockdown, such as food at home, housing and utilities, health items, communications and education. Yellow bars denote items restricted by the lockdown, such as food in restaurants, transport services, holidays, hotels and cultural services. Red bars denote postponable spending items, such as purchases of motor vehicles, clothing and footwear, and furnishings and furniture. Green bars show household saving. The chart shows an aggregate of Germany, Spain and France.

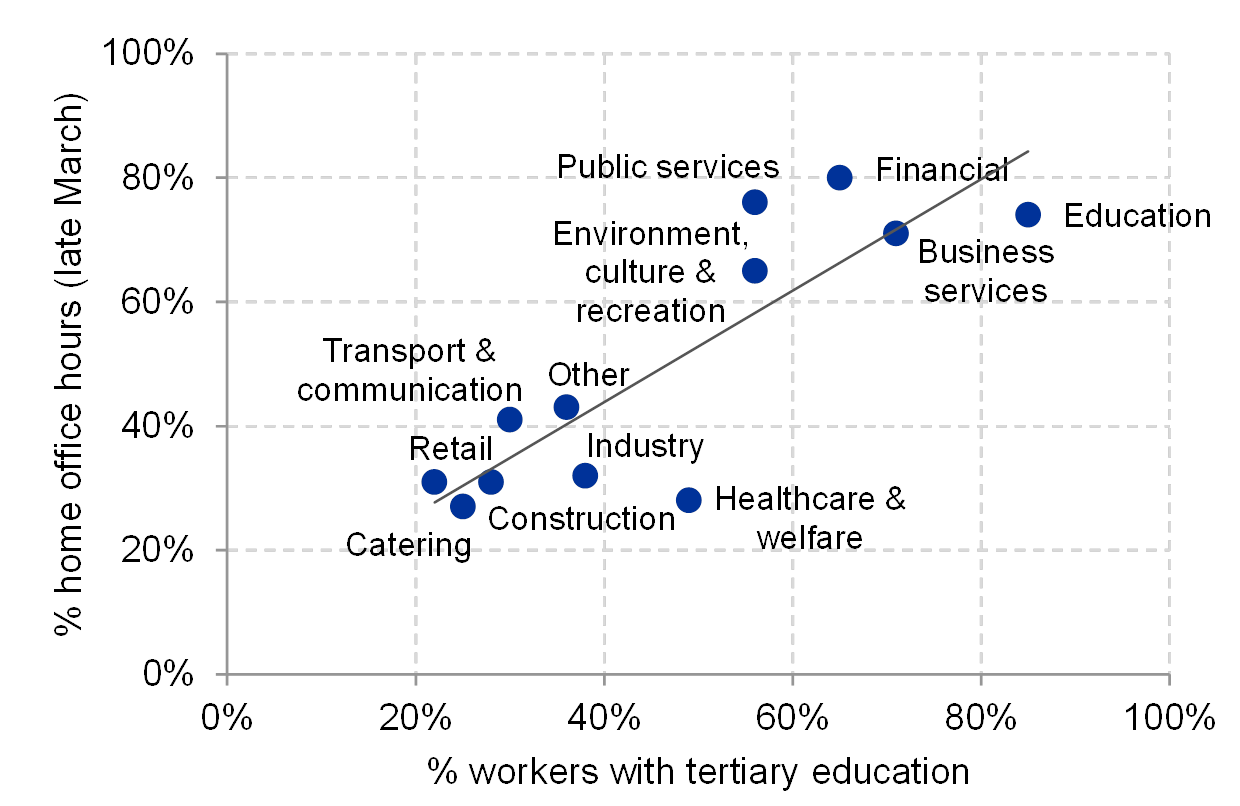

Furthermore, the impact of the lockdown measures is also associated with individuals’ education level. In the Netherlands, for example, sectors with a higher share of work hours spent in home office during the crisis tend to have a higher proportion of employees with tertiary education (Figure 15). Employees in these sectors are presumably less affected by short-time work schemes and income shortfalls, given that they were able to continue working from home during the pandemic period.

Figure 15

Share of workers with tertiary education vs. share of working hours in home office.

Percent

Source: von Gaudecker et al. (2020), Longitudinal Internet Studies for the Social Sciences (LISS), CentERdata/Tilburg University.

Note: Data refer to survey results obtained in the Netherlands between 20 March and 31 March 2020. Response rate: 80% (5,544 individuals).

The lockdown measures could also lead to a worsening of inequality for individuals who are still in school. For example, during the period of home schooling in the wake of the pandemic, students from US districts with higher average household incomes earned a higher number of badges for completing online courses relative to those from districts with lower incomes (Figure 16). The observed dispersion of learning outcomes is primarily problematic because it could lead to lasting differences in human capital accumulation, thus causing inequality to increase in the long run.

Figure 16

Students’ performance by estimated household income in the United States.

Index

Source: Zearn, Inc., Opportunity Insights.

Note: Average number of students using Zearn math teaching program (in a week) relative to January 6-February 7, 2020. The lines show ZIP codes in bottom 25% of income [low], 25%-75% [middle] and above 75% [high]. A similar chart was published by The Economist on 27 July 2020.

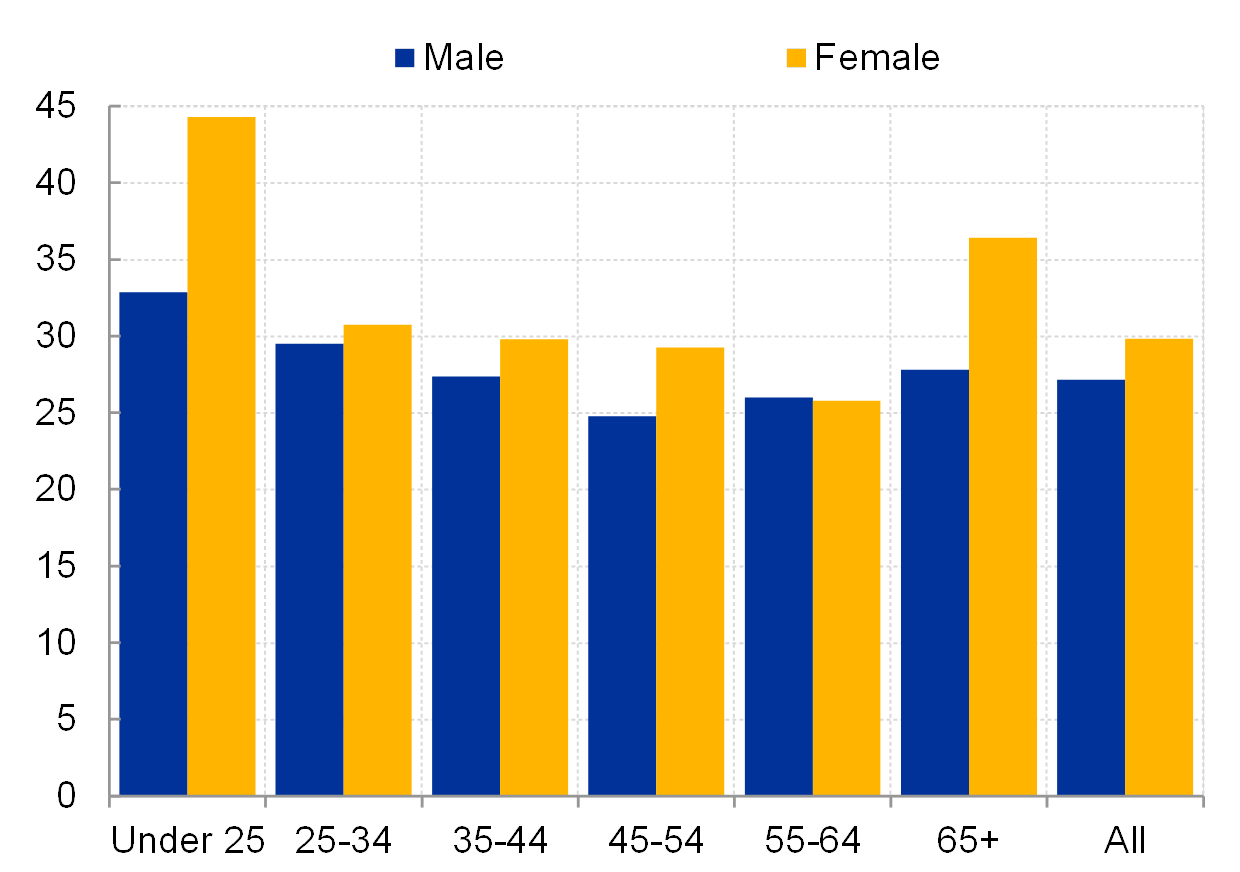

Finally, recent studies also indicate that the effects of lockdown measures can also be differentiated in terms of individuals’ age and gender.

On the one hand, the share of young employees in sectors that have been particularly affected by the government-imposed containment measures is relatively high. On the other hand, women across almost all age groups are more heavily affected by the restrictions than men (Figure 17).[9]

Figure 17

Share of employees in lockdown sectors by age and gender.

Percent

Source: EU Statistics on Income and Living Conditions (EU-SILC), 2018; Ireland and Slovakia 2017.

Note: The chart shows the distribution of the share of employees in lockdown sectors across age and gender.

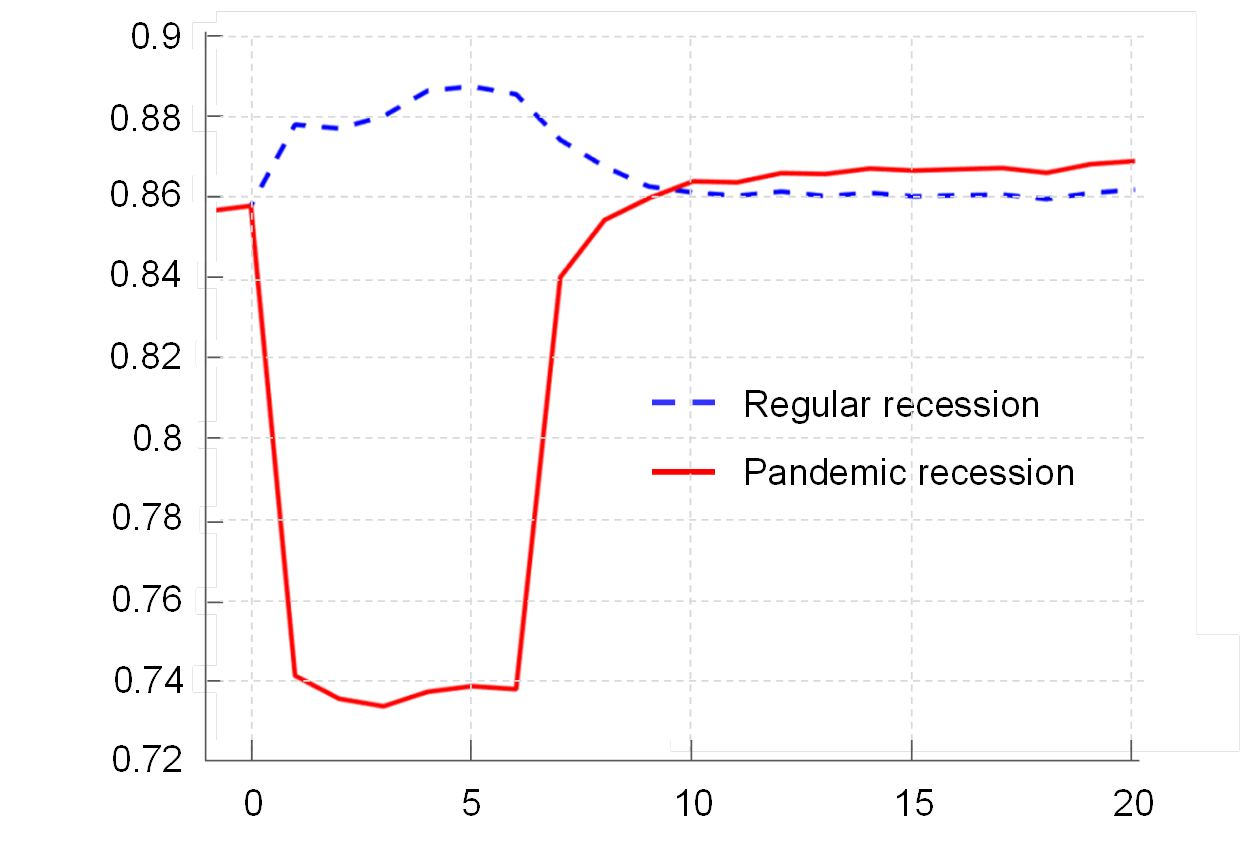

The crisis could also have an impact on the labour market participation of women. In a recent macroeconomic model that was calibrated on the basis of US data, Alon et al. (2020) show that during pandemics the ratio of labour hours supplied by women relative to men falls much more sharply than in “normal” recessions (Figure 18). The persistence of temporary financial losses on the labour market[10] could structurally entrench such gender differences.[11]

Figure 18

Share of employees in lockdown sectors by age and gender.

Ratio of labour hours supplied by women vs. men, quarters since start of recession

Source: Alon, Doepke, Olmstead-Rumsey and Tertilt (2020).

Note: Chart is based on Figure 4 in the latest available paper draft (August 2020).

The closure of childcare facilities and schools was a key element of the lockdown measures that were implemented in many countries. A renewed surge in infection numbers could result in such measures being reintroduced. Fuchs-Schündeln et al. (2020) estimate that, in Germany, up to 11% of employees could be forced to stop working and stay at home instead in case school closures are extended.[12] Adams et al. (2020) present survey data indicating that childcare duties imposed a much larger burden on women during the coronavirus crisis.[13]

Alon et al. (2020) conclude that women in particular will have to cope with substantial financial losses as a result of the additional burden due to childcare duties.[14] It is likely that single mothers with low incomes are particularly affected by such losses.

Collectively, the available evidence is consistent in concluding that government-imposed lockdown measures primarily affect people in lower income brackets, younger employees and women, especially those with children childcare duties. The containment measures are thus at least temporarily contributing to a reinforcement of existing social inequalities.

Closing remarks

I would now like to conclude my remarks.

The COVID-19 pandemic has affected different parts of our society in different ways. The heterogeneous evolution of case numbers resulted in lockdown measures of varying stringency, which were in part contingent on the sectoral composition of individual countries. As a result, the economic impact of the containment measures was more severe in some countries than in others. The decisive measures taken by fiscal policy makers at national and European level as well as the ECB’s monetary policy will help to mitigate a looming economic divergence between individual European countries.

It will be essential to find a common European response to these shared challenges, and to implement it on the basis of the ground-breaking decisions taken at the EU summit in July. The funds available under the Next Generation EU instrument should be used to strengthen the growth potential of all countries in a sustainable manner. In this context, measures to foster the transition of the economy to green and digital technologies should play a central role. At the same time, such measures can permanently reduce differences among individual euro area countries.

This is also beneficial for monetary policy. A lower degree of divergence in economic developments within the euro area increases the effectiveness of monetary policy measures.

Completing the architecture of the euro area would also facilitate the implementation of adequate European responses to common crises in the future. In a survey commissioned by the European Parliament, 69% of respondents indicate that they would support additional competences for European authorities in responding to a crisis like the coronavirus pandemic.[15]

Within countries, the impact of the crisis was by no means uniform either. In this context, disadvantaged individuals – including those with low incomes and education levels, younger workers and women – were far more heavily affected by the containment measures than others.

However, an increase in inequality as a result of the crisis is not inevitable. Fiscal policy is able to provide targeted support to specific industries and social groups who bear a particularly heavy burden due to the pandemic. Such support is not only about redistribution, but also about empowerment of individuals to cope with the inevitable structural change caused by the pandemic. Education and family policy are likely to play an important role in this context.

Within the remit of its mandate, monetary policy can have an impact on social inequality to the extent that its measures benefit lower income groups, given that these groups are most heavily affected by job losses. Beyond this effect, monetary policy does not possess targeted instruments to mitigate the distributional ramifications of the crisis on an individual level.

In the long run, the key objective should be to prevent permanent scarring effects due to a structural entrenchment of inequalities emerging in the context of the crisis.

Thank you very much for your attention.

- This is a translated version of the original speech (delivered in German). I would like to thank Jirka Slacalek and Joachim Schroth for their contributions to this speech.

- The ECB’s Macroeconomic Projection Exercise published in September 2020 is available at: https://www.ecb.europa.eu/pub/projections/html/ecb.projections202009_ecbstaff~0940bca288.en.html. The Broad Macroeconomic Projection Exercise published in March 2020 is available at: https://www.ecb.europa.eu/pub/pdf/other/ecb.projections202003_ecbstaff~dfa19e18c4.en.pdf.

- See also Eurostat, News release 88/2020, 3 June 2020, https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/documents/2995521/10294960/3-03062020-AP-EN.pdf/b823ec2b-91af-9b2a-a61c-0d19e30138ef; Bundesagentur für Arbeit (Federal Employment Agency), Monatsbericht zum Arbeits- und Ausbildungsmarkt, August 2020, https://www.arbeitsagentur.de/datei/arbeitsmarktbericht-august-2020_ba146633.pdf.

- Mongey, S., Pilossoph, L. and Weinberg, A. (2020), “Which workers bear the burden of social distancing policies?”, Covid Economics, Issue 12, pp. 69-86.

- Beland, L.-P., Brodeur, A. and Wright, T. (2020), “COVID-19, Stay-At-Home Orders and Employment: Evidence from CPS Data”, IZA Discussion Paper Series, Discussion Paper No 13282, May.

- Chetty, R., Friedman, J.N., Hendren, N., Stepner, M. and Opportunities Insight Team (2020), “Real-Time Economics: A New Public Platform to Analyze the Impacts of COVID-19 and Macroeconomic Policies Using Private Sector Data”, September, available at: https://opportunityinsights.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/tracker_paper.pdf.

- Furceri, D., Loungani, P., Ostry, J.D. and Pizzuto, P. (2020), “Will COVID-19 affect inequality? Evidence from past pandemics”, Covid Economics, Issue 12, pp. 138-157.

- Brinca, P., Holter, H. A., Krusell, P. und Malafry, L. “Fiscal multipliers in the 21st century”, Journal of Monetary Economics, Band 77, S. 53–69; Gross, T., Notowidigdo, M. J. und Wang, J., “The Marginal Propensity to Consume over the Business Cycle”, American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics, Band 12, Ausgabe 2, S. 351–384; Voinea, L., Lovin, H. und Cojocaru, A. (2018), “The impact of inequality on the transmission of monetary policy”, Journal of International Money and Finance, Band 85, S. 236–250.

- See also: Torrejón Pérez, S., Fana, M., González-Vázquez, I. and Fernández-Macías, E. (2020), “The asymmetric impact of COVID-19 confinement measures on EU labour markets”, VoxEU, 9 May.

- On the persistence of income losses on the labour market, see also: Stevens, A.H. (1997), “Persistent effects of job displacement: The importance of multiple job losses”, Journal of Labour Economics, 15 (1), pp. 165-188.

- Alon et al. (2020), by contrast, assume that the negative effects in the short term can be offset by men becoming more heavily involved in childcare in the long term.

- Fuchs-Schündeln, N., Kuhn, M. and Tertilt, M. (2020), “The short-run macro implications of school and childcare closures”, VoxEU, 3 May.

- Adams, A., Boneva, T., Golin, M. and Rauh, C. (2020), “Inequality in the impact of the Coronavirus shock: evidence from real-time surveys”, CEPR Discussion Paper 14665, Centre for Economic Policy Research, April.

- Alon, T.M., Doepke, M., Olmstead-Rumsey, J. and Tertilt, M. (2020), “The impact of COVID-19 on gender equality”, NBER Working Paper Series, Working Paper No 26947, National Bureau of Economic Research, April.

- https://www.europarl.europa.eu/news/en/press-room/20200525IPR79717/eu-citizens-want-more-competences-for-the-eu-to-deal-

with-crises-like-covid-19.

Европейска централна банка

Генерална дирекция „Комуникации“

- Sonnemannstrasse 20

- 60314 Frankfurt am Main, Germany

- +49 69 1344 7455

- media@ecb.europa.eu

Възпроизвеждането се разрешава с позоваване на източника.

Данни за контакт за медиите-

18 September 2020